CHAPTER XXVI

NEW YORK AND BOSTON

I TOOK two days’ rest before going to the theater, for I could feel the movement of the boat all the time, my head was dizzy, and it seemed to me as though the ceiling moved up and down. The twelve days on the sea had quite upset my health. I sent a line to the stage manager telling him that we would rehearse on Wednesday, and on that day as soon as luncheon was over I went to the Booth Theater, where our performances were to take place. At the door reserved for the artistes I saw a compact, swaying crowd, very much animated and gesticulating. These strange-looking individuals did not belong to the artiste world. They were not reporters, either, for I knew them too well, alas! to be mistaken in them. They were not there out of curiosity, either, these people, for they seemed too much occupied and then, too, there were only men. When my carriage drew up one of them rushed forward to the door of it and then returned to the swaying crowd. “Here she is, here she is!” I heard, and then all these common men with their white neckties and questionable-looking hands, with their coats flying open and trousers whose knees were worn and dirty looking, crowded behind me into the narrow passage leading to the staircase. I did not feel very easy in my mind, and I mounted the stairs rapidly. Several persons were waiting for me at the top, Mr. Abbey, Jarrett, and also some reporters, two gentlemen, and a charming and most distinguished woman whose friendship I have kept ever since, although she does not care much for French people. I saw Mr. Abbey, who was usually very dignified and cold, advance in the most gracious and courteous way to one of the men who were following me. They raised their hats to each other and, followed by the strange and brutal-looking regiment, they advanced toward the center of the stage. I then saw the strangest of sights. In the middle of the stage were my forty-two trunks. In obedience to a sign twenty of the men came forward and placing themselves, each one between two trunks, with a quick movement with their right and left hands they lifted the lids of the trunks on the right and left of them. Jarrett with frowns and an unpleasant grin held out my keys to them. He had asked me that morning for my keys for the customs. “Oh, it’s nothing!” he said, “don’t be uneasy,” and the way in which my luggage had always been respected in other countries had given me perfect confidence about it. The principal personage of the ugly group came toward me accompanied by Abbey, and Jarrett explained things to me. The man was an official from the American customhouse. The custom office is an abominable institution in every country, but worse in America than anywhere else. I was prepared for all this and was most affable to the tormenter of a traveler’s patience. He raised the melon which served him for a hat and, without taking his cigar out of his mouth made some incomprehensible remark to me. He then turned to his regiment of men, made an abrupt sign with his hand, and uttered some word of command, whereupon the forty dirty hands of these twenty men proceeded to forage among my velvets, satins, and laces. I rushed forward to save my poor dresses from such outrageous violations, and I ordered our costume maker to lift my gowns out one at a time, which she accordingly did, aided by my maid, who was in tears at the small amount of respect shown by these boors to all my beautiful, fragile things. Two ladies had just arrived, very noisy and businesslike. One of them was short and stout, her nose seemed to begin at the roots of her hair; she had round, placid-looking eyes and a mouth like a snout; her arms she was hiding timidly behind her heavy, flabby bust and her ungainly knees seemed to come straight out of her groin. She looked like a seated cow. Her companion was like a terrapin, with her little, black, evil-looking head at the end of a neck which was too long, and very stringy. She kept shooting it out of her boa and drawing it back with the most incredible rapidity. The rest of her body bulged out.... These two delightful persons were the dressmakers sent for by the customhouse to estimate my costumes. They glanced at me in a furtive way and gave a little bow, full of bitterness and jealous rage at the sight of my dresses, and I was quite aware that two more enemies had now come upon the scene. These two odious shrews began to chatter and argue, pawing and crumpling my dresses and cloaks at the same time. They kept exclaiming in the most emphatic way: “Oh, how beautiful! What magnificence! What luxury! All our customers will want gowns like these and we shall never be able to make them! It will be the ruin of all the American dressmakers.” They were working up the judges into a state of excitement for this “chiffon court martial.” They kept lamenting, then going into raptures and asking for “justice” against foreign invasion. The ugly band of men nodded their heads in approval and spat on the ground to affirm their independence. Suddenly the Terrapin turned on one of the inquisitors:

“Oh, isn’t it beautiful! Show it them, show it them!” she exclaimed, seizing on a dress all embroidered with pearls, which I wore in “La Dame aux Camélias.”

“This dress is worth at least $10,000,” she said and then, coming up to me she asked: “How much did you pay for that dress, madame?”

I ground my teeth together and would not answer, for just at that moment I should have enjoyed seeing the Terrapin in one of the saucepans in the Albemarle Hotel kitchen. It was nearly half past five and my feet were frozen. I was half dead, too, with fatigue and suppressed anger. The rest of the examination was postponed until the next day, and the ugly band of men offered to put everything back in the trunk, but I objected to that. I sent out for five hundred yards of blue tarlatan to cover over the mountain of dresses, hats, cloaks, shoes, laces, linen, stockings, furs, gloves, etc., etc. They then made me take my oath to remove nothing, for they had such charming confidence in me, and I left my butler there in charge. He was the husband of Félicie, my maid, and a bed was put up for him on the stage. I was so nervous and upset that I wanted to go somewhere far away, to have some fresh air, and to stay out for a long time. A friend offered to take me to see the Brooklyn Bridge.

“That masterpiece of American genius will make you forget the petty miseries of our red-tape affairs,” he said gently, and so we set out for Brooklyn Bridge.

Oh, that bridge! It is insane, admirable, imposing, and it makes one feel proud. Yes, one is proud to be a human being when one realizes that a human brain has created and suspended in the air, fifty yards from the ground, that fearful thing which bears a dozen trains filled with passengers, ten or twelve tram cars, a hundred cabs, carriages, and carts, and thousands of foot passengers, and all that moving along together amidst the uproar of the music of the metals, clanging, clashing, grating, and groaning under the enormous weight of people and things. The movement of the air caused by this frightful, tempestuous coming and going, caused me to feel giddy and stopped my breath. I made a sign for the carriage to stand still and I closed my eyes. I then had a strange indefinable sensation of universal chaos. I opened my eyes again when my brain was a little more tranquil and I saw New York stretching out along the river, wearing its night ornaments, which glittered as much through its dress with thousands of electric lights as the firmament with its tunic of stars. I returned to the hotel reconciled with this great nation. I went to sleep tired in body but rested in mind, and had such delightful dreams that I was in a good humor the following day. I adore dreams, and my sad, unhappy days are those which follow dreamless nights. My great grief is that I cannot choose my dreams. How many times I have done all in my power at the end of a happy day to make myself dream a continuation of it! How many times I have called up the faces of those I love just before falling asleep! but my thoughts wander and carry me off elsewhere, and I prefer that or even a disagreeable dream to none at all. When I am asleep my body has an infinite sense of enjoyment, but it is torture to me for my thoughts to slumber. My vital forces rebel against such negation of life. I am quite willing to die once for all, but I object to slight deaths such as those of which one has the sensation on dreamless nights. When I awoke, my maid told me that Jarrett was waiting for me to go to the theater, so that the valuation of my costumes could be terminated. I sent word to Jarrett that I had seen quite enough of the regiment from the customhouse, and I asked him to finish everything without me, as Mme. Guérard would be there. During the next two days the Terrapin, the Seated Cow and the Black Band made notes for the customhouse, took sketches for the papers and patterns of my dresses for customers. I began to get impatient, as we ought to have been rehearsing. Finally, I was told on Thursday morning that the business was over, and that I could not have my trunks until I had paid 28,000 francs for duty. I was seized with such a violent fit of laughing that poor Abbey, who had been terrified, caught it from me and even Jarrett showed his cruel teeth.

“My dear Abbey,” I exclaimed, “arrange as you like about it, but I must make my début on Monday, the 8th of November, and to-day is Thursday. I shall be at the theater on Monday to dress. See that I have my trunks, for there was nothing about the customhouse in my contract. I will pay half, though, of what you have to give.” The 28,000 francs were handed over to an attorney who made a claim in my name on the Board of Customs. My trunks were left with me, thanks to this deposit, and the rehearsals commenced at Booth’s Theater.

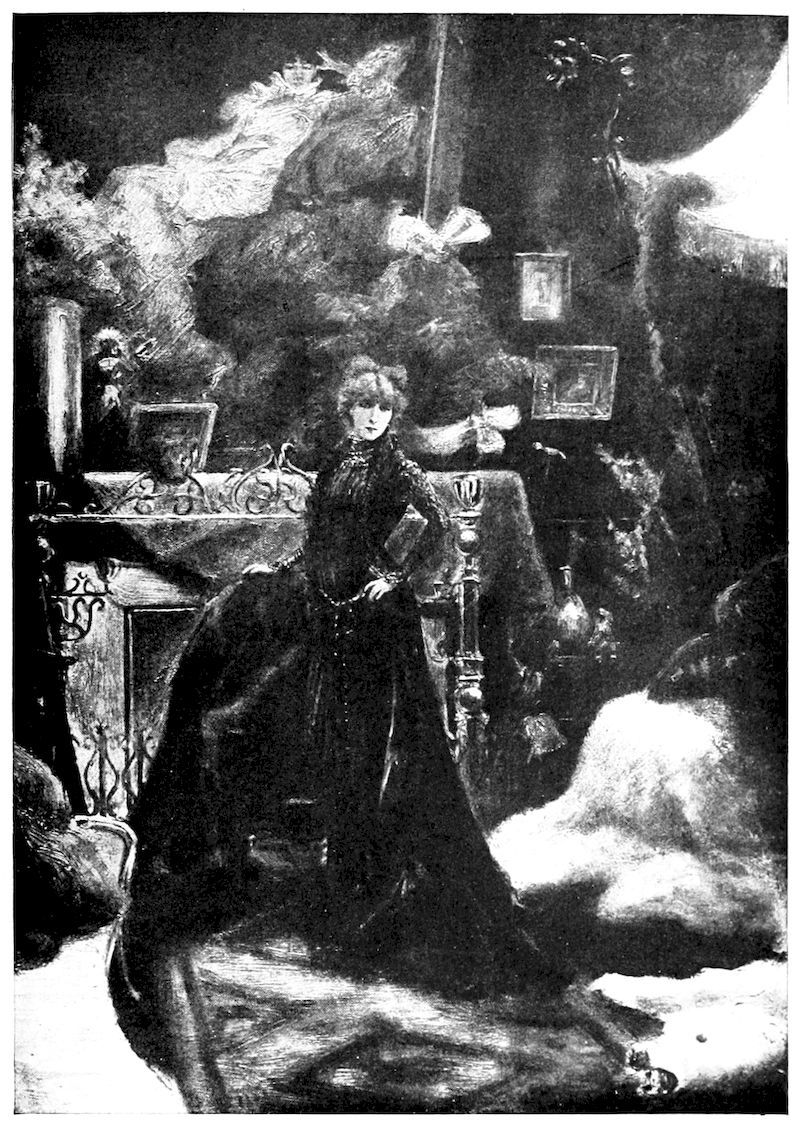

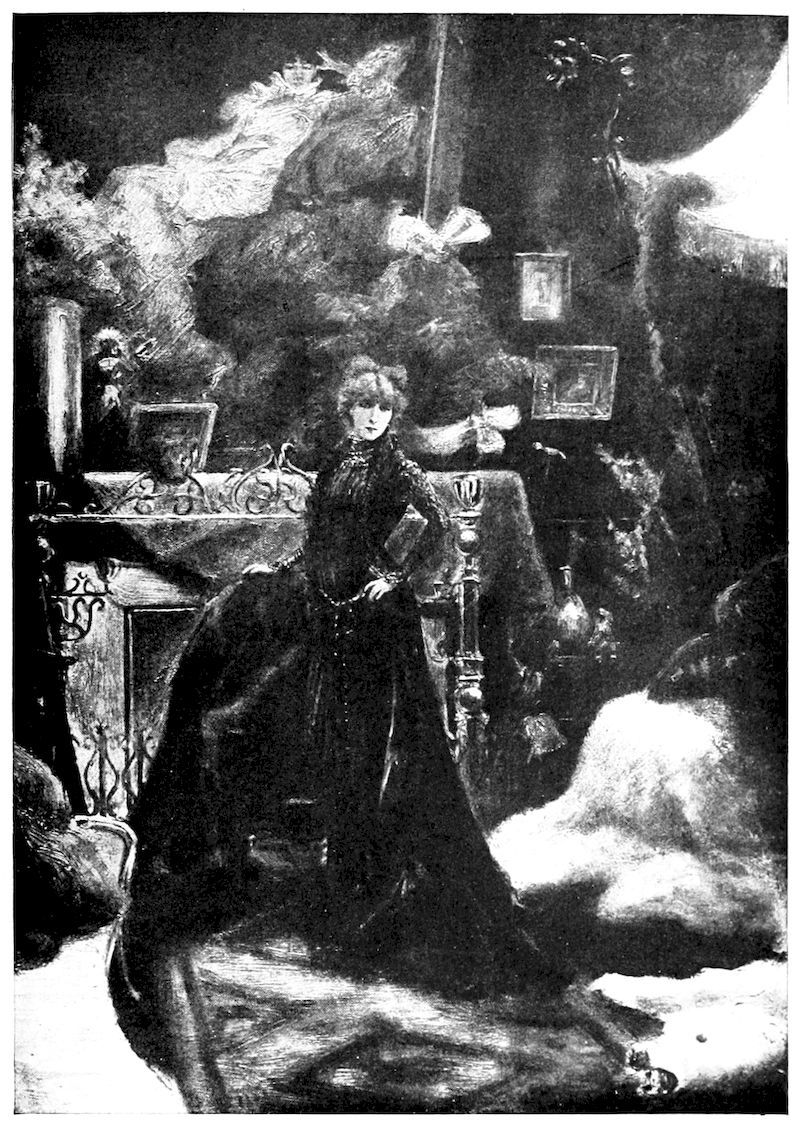

SARAH BERNHARDT AT HOME, BY WALTER SPINDLER.

On Monday evening, November 8th, at 8.30, the curtain rose for the first performance of “Adrienne Lecouvreur.” The house was crowded and the seats, which had been sold to the highest bidders and then sold by them again, had fetched exorbitant prices. I was awaited with impatience and curiosity, but not with any sympathy. There were no young girls present, as the piece was too immoral. (Poor Adrienne Lecouvreur!) The audience was very polite to the artistes of my company, but rather impatient to see the strange person who had been announced to them. The curtain fell at the end of the first act and Adrienne had not appeared. One of the audience, very much annoyed, asked to see Mr. Henry Abbey. “I want my money back,” he said, “as la Bernhardt is not in every act.” Abbey refused to return the money to the extraordinary individual and as the curtain was going up he hurried back to take possession of his seat again. My appearance was greeted by several rounds of applause, which I believe had been paid for in advance by Abbey and Jarrett. I commenced and the sweetness of my voice as in the fable of the “Two Pigeons” worked the miracle. The whole house this time burst out into hurrahs. A current of sympathy was established between my public and myself. Instead of the hysterical skeleton that had been announced to them, they had before them a very frail-looking creature with a sweet voice. The fourth act was applauded and Adrienne’s rebellion against the Princesse de Bouillon stirred the whole house. Finally, in the fifth act, when the unfortunate artiste is dying, poisoned by her rival, there was quite a manifestation and everyone was deeply moved.

At the end of the third act all the young men were sent off by the ladies to find all the musicians they could get together, and to my surprise and delight on arriving at my hotel a charming serenade was played for me while I was at supper. The crowd had assembled under my windows at the Albemarle Hotel and I was obliged to go out on to the balcony several times to bow and to thank this public, which I had been told I should find cold and prejudiced against me. From the bottom of my heart I also thanked all my detractors and slanderers, as it was through them that I had had the pleasure of fighting, with the certainty of conquering. The victory was all the more enjoyable as I had not dared to hope for it.

I gave twenty-seven performances in New York. The plays were “Adrienne Lecouvreur,” “Froufrou,” “Hernani,” “La Dame aux Camélias,” “Le Sphinx,” “L’Etrangère.” The average receipts were 20,342 francs for each performance, including matinées. The last performance was given on Saturday, December 4th, as a matinée, for my company had to leave that night for Boston and I had reserved the evening to go to Mr. Edison, at Menlo Park, where I had a reception worthy of fairyland.

Oh, that matinée of Saturday, December 4th! I can never forget it! When I got to the theater to dress it was midday, for the matinée was to commence at half past one. My carriage stopped, not being able to get along, for the street was filled by ladies, sitting on chairs which they had borrowed from the neighboring shops, or on folding seats which they had brought themselves. The play was “La Dame aux Camélias.” I had to get out of my carriage and walk about twenty-five yards on foot in order to get to the stage door. It took me twenty-five minutes to do it. People shook my hands and begged me to come back. One lady took off her brooch and pinned it in my mantle—a modest brooch of amethysts surrounded by fine pearls, but certainly for the giver the brooch had its value. I was stopped at every step. One lady pulled out her notebook and begged me to write my name. The idea took like lightning. Small boys under the care of their parents wanted me to write my name on their cuffs. My arms were full of small bouquets which had been pushed into my hands. I felt behind me some one tugging at the feather in my hat. I turned round sharply. A woman with a pair of scissors in her hand had tried to cut off a lock of my hair, but she had only succeeded in cutting the feather out of my hat. In vain Jarrett signalled and shouted—I could not get along. They sent for the police, who delivered me, but without any ceremony, either for my admirers or for myself. They were real brutes, those policemen, and made me very angry. I played “La Dame aux Camélias” and I counted seventeen calls after the third act and twenty-nine after the fifth. In consequence of the cheering and calls the play had lasted an hour longer than usual and I was half dead with fatigue. I was just about to go to my carriage to get back to my hotel when Jarrett came to tell me that there were more than 50,000 people waiting outside. I fell back on a chair, tired and disheartened.

“Oh, I will wait till the crowd has dispersed! I am tired out. I can do no more.”

But Henry Abbey had an inspiration of genius.

“Stay,” said he to my sister, “put on madame’s hat and boa and take my arm. And take also these bouquets—give me what you cannot carry. And now we will go to your sister’s carriage and make our bow.”

He said all this in English and Jarrett translated it to my sister who lent herself to this little comedy very willingly. During this time Jarrett and I got into Abbey’s carriage, which was stationed in front of the theater where no one was waiting. And it was fortunate we took this course, for my sister only got back to the Albemarle Hotel an hour later, very tired, but very much amused. Her resemblance to myself, my hat, my boa, and the darkness of night had been the accomplices of the little comedy which we had offered to my enthusiastic public.

We had to set out at nine o’clock for Menlo Park. We had to dress in traveling costume, for the following day we were to leave for Boston and my trunks had gone that day with my company, which preceded me by several hours.

The dinner was, as usual, very bad, for in those days in America the food was unspeakably awful. At ten o’clock we took the train—a pretty, special train all decorated with flowers and banners, which they had been kind enough to prepare for me. But it was a painful journey, all the same, for at each instant we had to pull up to allow another train to pass, or an engine to maneuver, or to wait to pass over the points. It was two o’clock in the morning when the train at last reached the station of Menlo Park, the residence of Thomas Edison.

It was a very dark night and the snow was falling silently in heavy flakes. A carriage was waiting and the one lamp of this carriage served to light up the whole station, for orders had been given that the electric lights should be put out. I found my way with the help of Jarrett and some of my friends who had accompanied us from New York. The intense cold froze the snow as it fell, and we walked over veritable blocks of sharp, jagged ice, which crackled under our feet. Behind the first carriage was another heavier one, with only one horse and no lamp. There was room for five or six persons to crowd into this. We were ten in all; Jarrett, Abbey, my sister, and I took our places in the first one, leaving the others to get into the second. We looked like a band of conspirators, the dark night, the two mysterious carriages, the silence caused by the icy coldness, the way in which we were muffled in our furs, and our anxious expressions as we glanced around us—all this made our visit to the celebrated Edison resemble a scene out of an operetta.

The carriage rolled along, sinking deep into the snow and jolting terribly; the jolts made us dread every instant some tragi-comic accident. I cannot tell how long we had been rolling along for, lulled by the movement of the carriage and buried in my warm furs, I was quietly dozing when a formidable “Hip-hip-hurrah!” made us all jump, my traveling companions, the coachman, the horse, and I. As quick as thought the whole country was suddenly illuminated. Under the trees, on the trees, among the bushes, along the garden walks, lights flashed forth triumphantly. The wheels of the carriage turned a few times more and then drew up at the house of the famous Thomas Edison. A group of people awaited us on the veranda, four men, two ladies, and a young girl. My heart began to beat quickly as I wondered which of these men was Edison. I had never seen his photograph and I had the greatest admiration for his genius. I sprang out of the carriage and the dazzling electric light made it seem like daytime to us. I took the bouquet which Mrs. Edison offered me and thanked her for it, but all the time I was endeavoring to discover which of these was the Great Man. They all four advanced toward me, but I noticed the flush that came into the face of one of them and it was so evident from the expression of his blue eyes that he was intensely bored that I guessed this was Edison. I felt confused and embarrassed myself, for I knew very well that I was causing inconvenience to this man by my visit. He, of course, imagined that it was due to the idle curiosity of a foreigner, eager to court publicity. He was no doubt thinking of the interviewing in store for him the following day, and of the stupidities he would be made to utter. He was suffering beforehand at the idea of the ignorant questions I should ask him, of all the explanations he would, out of politeness, be obliged to give me, and at that moment Thomas Edison took a dislike to me. His wonderful blue eyes, more luminous than his incandescent lamps, enabled me to read his thoughts. I immediately understood that he must be won over, and my combative instinct had recourse to all my powers of fascination, in order to vanquish this delightful but bashful savant. I made such an effort and succeeded so well that, half an hour later, we were the best of friends. I followed him about quickly, climbing up staircases as narrow and steep as ladders, crossing bridges suspended in the air above veritable furnaces, and he explained everything to me. I understood all, and I admired him more and more, for he was so simple and charming, this king of light. As we leaned over a slightly unsteady bridge, above the terrible abyss in which immense wheels, encased in wide thongs, were turning, tacking about, and rumbling, he gave various orders in a clear voice and light then burst forth on all sides, sometimes in sputtering, greenish jets, sometimes in quick flashes or in serpentine trails like streams of fire. I looked at this man of medium size, with rather a large head and a noble-looking profile, and I thought of Napoleon I. There is certainly a great physical resemblance between these two men, and I am sure that one compartment of their brain would be found to be identical. Of course I do not compare their genius. The one was “destructive” and the other “creative,” but while I execrate battles, I adore victories and, in spite of his errors, I have raised an altar in my heart to that god of Glory, Napoleon! I therefore looked at Edison thoughtfully, for he reminded me of the great man who was dead. The deafening sound of the machinery, the dazzling rapidity of the changes of light—all that together made my head whirl and, forgetting where I was, I leaned for support on the slight balustrade which separated me from the abyss beneath. I was so unconscious of all danger that, before I had recovered from my surprise, Edison had helped me into an adjoining room and installed me in an armchair without my realizing how it had all happened. He told me afterwards that I had turned dizzy.

After having done the honors of his telephonic discovery and of his astonishing phonograph, Edison offered me his arm and took me to the dining-room where I found his family assembled. I was very tired and did justice to the supper that had been so hospitably prepared for us.

I left Menlo Park at four o’clock in the morning and this time the country round, the roads, and the station were all lighted up, à giorno, by the thousands of jets of my kind host. What a strange power of suggestion the darkness has! I thought I had traveled a long way that night, and it seemed to me that the roads were impracticable. It proved to be quite a short distance and the roads were charming, although they were covered with snow. Imagination had played a great part during the journey to Edison’s house, but reality played a much greater one during the same journey back to the station. I was enthusiastic in my admiration of the inventions of this man, and I was charmed with his timid graciousness and perfect courtesy, and with his profound love of Shakespeare.

The next day or rather that same day, for it was then four in the morning, I started after my company for Boston. Mr. Abbey, my impresario, had arranged for me to have a delightful “car,” but it was nothing like the wonderful Pullman car that I was to have from Philadelphia for continuing my tour. I was very much pleased with this one, nevertheless. In the middle of the room there was a real bed, large and comfortable, on a brass bedstead. Then there was an armchair, a pretty dressing table, a basket tied up with ribbons for my dog, and flowers everywhere, but flowers without overpowering perfume. In the car adjoining mine were my own servants, who were also very comfortable. I went to bed feeling thoroughly satisfied and woke up at Boston.

A large crowd was assembled at the station. There were reporters and curious men and women, a public decidedly more interested than friendly, not badly intentioned but by no means enthusiastic. Public opinion in New York had been greatly occupied with me during the past month. I had been so much criticised and glorified. Calumnies of all kinds, stupid and disgusting, foolish and odious, had been circulated about me. Some people blamed and others admired the disdain with which I had treated these turpitudes, but everyone knew that I had won in the end, and that I had triumphed over all and everything. Boston knew, too, that clergymen had preached from their pulpits saying that I had been sent by the Old World to corrupt the New World, that my art was an inspiration from hell, etc., etc. Everyone knew all this, but the public wanted to see for itself. Boston belongs especially to the women. Tradition says that it was a woman who first set foot in Boston. Women form the majority there. They are puritanical with intelligence, and independent with a certain grace. I passed between the two lines formed by this strange, courteous, and cold crowd, and, just as I was about to get into my carriage a lady advanced toward me and said: “Welcome to Boston, madame.”

“Welcome, madame,” and she held out a soft little hand to me. (American women generally have charming hands and feet.) Other people now approached and smiled, and I had to shake hands with many of them. I took a fancy to this city at once, but all the same I was furious for a moment when a reporter sprang on to the steps of the carriage just as we were driving away. He was in a greater hurry and more audacious than any of the others, but he was certainly overstepping the limits and I pushed the wretched man back angrily. Jarrett was prepared for this and saved him by the collar of his coat; otherwise he would have fallen down on the pavement as he deserved.

“At what time will you come and get on the whale to-morrow?” this extraordinary personage asked. I gazed at him in bewilderment. He spoke French perfectly and repeated his question.

“He’s mad,” I said in a low voice to Jarrett.

“No, madame, I am not mad, but I should like to know at what time you will come and get on the whale. It would be better perhaps to come this evening, for we are afraid it may die in the night, and it would be a pity for you not to come and pay it a visit while it still has breath.”

He went on talking, and as he talked, he half seated himself beside Jarrett who was still holding him by the collar, lest he should fall out of the carriage.

“But, monsieur,” I exclaimed. “What do you mean? What is all this about a whale?”

“Ah! madame,” he replied, “it is admirable, enormous. It is in the harbor basin and there are men employed day and night to break the ice all round it.”

He broke off suddenly and standing on the carriage step he clutched the driver.

“Stop! Stop!” he called out. “Hi-Hi, Henry—come here—here’s madame, here she is!”

The carriage drew up, and without any further ceremony he jumped down and pushed into my carriage a little man, square all over, who was wearing a fur cap pulled down over his eyes, and an enormous diamond in his cravat. He was the strangest type of the old-fashioned Yankee. He did not speak a word of French, but he took his seat calmly by Jarrett, while the reporter remained half sitting and half hanging on to the vehicle. There had been three of us when we started from the station, and we were five when we reached the Hotel Vendome. There were a great many people awaiting my arrival, and I was quite ashamed of my new companion. He talked in a loud voice, laughed, coughed, spat, addressed everyone, and gave everyone invitations. All the people seemed to be delighted. A little girl threw her arms round her father’s neck, exclaiming: “Oh, yes, papa, do please let us go!”

“Well, but we must ask madame,” he replied and he came up to me in the most polite and courteous manner. “Will you kindly allow us to join your party when you go to see the whale to-morrow?” he asked.

“But, monsieur,” I answered, delighted to have to do with a gentleman once more, “I have no idea what all this means. For the last quarter of an hour this reporter and that extraordinary man have been talking about a whale. They declare, authoritatively, that I must go and pay it a visit and I know absolutely nothing about it at all. These two gentlemen took my carriage by storm, installed themselves in it without my permission and, as you see, are giving invitations in my name to people I do not know, asking them to go with me to a place about which I know nothing, for the purpose of paying a visit to a whale which is to be introduced to me and which is waiting impatiently to die in peace.”

The kindly disposed gentleman signed to his daughter to come with us and, accompanied by them, and by Jarrett, and Mme. Guérard, I went up in an elevator to the door of my suite of rooms. I found my apartments hung with valuable pictures and full of magnificent statues. I felt rather disturbed in my mind, for among these objects of art were two or three very rare and beautiful things which I knew must have cost an exorbitant price. I was afraid lest any of them should be stolen and I spoke of my fear to the proprietor of the hotel.

“Mr. X——, to whom the knickknacks belong,” he answered, “wishes you to have them to look at as long as you are here, mademoiselle, and when I expressed my anxiety about them to him just as you have done to me, he merely remarked that ‘it was all the same to him.’ As to the pictures, they belong to two wealthy Bostonians.” There was among them a superb Millet which I should have liked very much to own. After expressing my gratitude, and admiring these treasures, I asked for an explanation of the story of the whale, and Mr. Max Gordon, the father of the little girl, translated for me what the little man in the fur cap had said. It appeared that he owned several fishing boats which he sent out for codfishing for his own benefit. One of these boats had captured an enormous whale, which still had the two harpoons in it. The poor creature, thoroughly exhausted with its struggles, was several miles farther along the coast, but it had been easy to capture it and bring it in triumph to Henry Smith, the owner of the boats. It was difficult to say by what freak of fancy and by what turn of the imagination this man had arrived at associating in his mind the idea of the whale and my name as a source of wealth. I could not understand it, but the fact remained that he insisted in such a droll way and so authoritatively and energetically that the following morning at seven o’clock, fifty persons assembled, in spite of the icy cold rain, to visit the basin of the quay. Mr. Gordon had given orders that his mail coach with four beautiful horses should be in readiness. He drove himself, and his daughter, Jarrett, my sister, Mme. Guérard, and another elderly lady, whose name I have forgotten, were with us. Seven other carriages followed. It was all very amusing indeed. On our arrival at the quay, we were received by this comic Henry, shaggy looking this time from head to foot, and his hands encased in fingerless woolen gloves. Only his eyes and his huge diamond shone out from his furs. I walked along the quay, very much amused and interested. There were a few idlers looking on also and alas! three times over alas!—there were reporters. Henry’s shaggy paw then seized my hand and he drew me along with him quickly to the staircase. I barely escaped breaking my neck at least a dozen times. He pushed me along, made me stumble down the ten steps of the basin and I next found myself on the back of the whale. They assured me that it still breathed; I should not like to affirm that it really di