CHAPTER XXVII

I VISIT MONTREAL

We played “Hernani” that night to a full house. The seats had been sold to the highest bidders, and considerable prices were obtained for them. We gave fifteen performances at Boston at an average of 19,000 francs for each performance. I was sorry to leave that city, as I had spent two charming weeks there, my mind all the time on the alert when holding conversations with the Boston women. They are Puritans from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot, but they are indulgent and there is no bitterness about their puritanism. What struck me most about the women of Boston was the harmony and softness of their gestures. Brought up among the severest and harshest of traditions, the Bostonian race seems to me to be the most refined and the most mysterious of all the American races. As the women are in the majority in Boston, many of the young girls will remain unmarried. All their vital forces which they cannot expend in love and in maternity they employ in fortifying and making supple the beauty of their body, by means of exercise and sports, without losing any of their grace. All the reserves of heart are expended in intellectuality. They adore music, the theater, literature, painting, and poetry. They know everything and understand everything, are chaste and reserved, and neither laugh nor talk very loudly.

They are as far removed from the Latin race as the North Pole is from the South Pole, but they are interesting, delightful, and captivating.

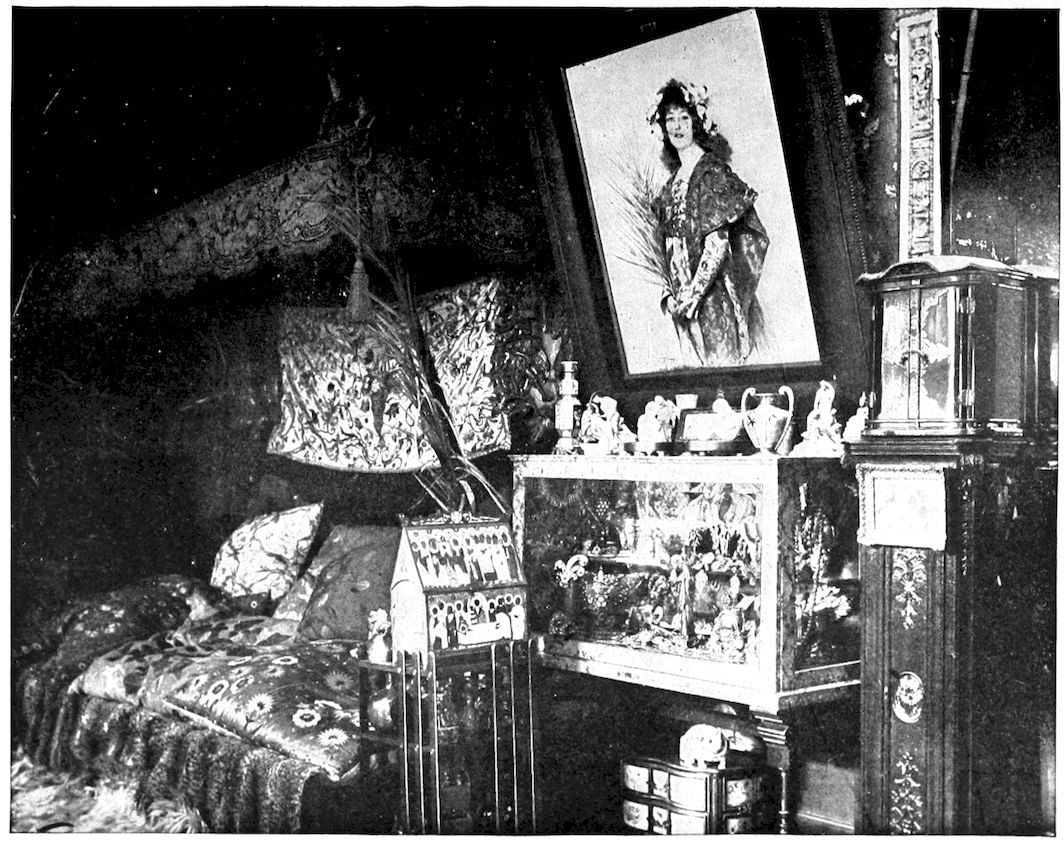

SARAH BERNHARDT AS DOÑA SOL IN “HERNANI.”

It was, therefore, with a rather heavy heart that I left Boston for New Haven, and to my great surprise on arriving at the hotel at New Haven, I found Henry Smith there, the famous whale man. “Oh, heavens!” I exclaimed, flinging myself into an armchair, “what does this man want now with me?”

I was not left in ignorance very long for the most infernal noise of brass instruments, drums, trumpets, and I should think saucepans, drew me to the window. I saw an immense carriage surrounded by an escort of negroes dressed as minstrels. On this carriage was an abominable, monstrous, colored advertisement representing me standing on the whale, tearing away its blade while it struggled to defend itself. Some sandwich men followed with posters on which were written the following words: “Come and see the enormous cetacea which Sarah Bernhardt killed by tearing out its whalebone for her corsets. These are made by Mme. Lily Noé who lives, etc.” Still other sandwich men carried posters with these words: “The whale is just as flourishing (sic) as when it was alive. It has five hundred dollars’ worth of salt in its stomach, and every day the ice upon which it was resting is renewed at a cost of one hundred dollars!”

My face turned more livid than that of a corpse and my teeth chattered with fury on seeing this. Henry Smith advanced toward me and I struck him in my anger, and then rushed away to my room, where I sobbed with vexation, disgust, and utter weariness. I wanted to start back to Europe at once, but Jarrett showed me my contract. I then wanted to take steps to have this odious exhibition stopped and in order to calm me, I was promised that this should be done, but in reality nothing was done at all. Two days later I was at Hartford and the same whale was there. It continued its tour as I continued mine. They gave it more salt, and renewed its ice, and it went on its way, so that I came across it everywhere. I took proceedings about it, but in every state I was obliged to begin all over again, as the law varied in the different states. And every time I arrived at a fresh hotel I found there an immense bouquet awaiting me with the horrible card of the showman of the whale. I threw his flowers on the ground and trampled on them, and much as I love flowers, I had a horror of these. Jarrett went to see the man and begged him not to send me any more bouquets, but it was all of no use as it was the man’s way of avenging the box on the ears I had given him. Then, too, he could not understand my anger. He was making any amount of money and had even proposed that I should accept a percentage of the receipts. Ah! I would willingly have killed that execrable Smith, for he was poisoning my life. I could see nothing else in all the different cities I visited, and I used to shut my eyes on the way from the hotel to the theater. When I heard the minstrels I used to fly into a rage and turn green with anger. Fortunately, I was able to rest when once I reached Montreal, where I was not followed by this show. I should certainly have been ill if it had continued, as I saw nothing but that, I could think of nothing else, and my very dreams were about it. It haunted me, it was an obsession and a perpetual nightmare. When I left Hartford, Jarrett swore to me that Smith would not be at Montreal as he had been taken suddenly ill. I strongly suspected that Jarrett had found a way of administering to him some violent kind of medicine which had stopped his journeying for the time. I felt sure of this, as the ferocious gentleman laughed so heartily en route, but anyhow I was infinitely grateful to him for ridding me of the man for the present.

For a long time, ever since my earliest childhood, I had dreamed about Canada. I had always heard my godfather regret, with considerable fury, the surrender of that territory by France to England.

I had heard him enumerate, without very clearly understanding them, the pecuniary advantages of Canada, the immense fortune that lay in its lands, etc. ... and that country had seemed to my imagination the far-off promised land.

Awakened some considerable time previous by the strident whistle of the engine, I asked what time it was. Eleven o’clock, I was informed. We were within fifteen minutes of the station. The sky was black and smooth, like a steel shield. Lanterns placed at distant intervals caught the whiteness of the snow heaped up there for how many days!... The train stopped suddenly and then started again with such a slow and timid movement that I fancied that there might be a possibility of its running off the rails. But a deadened sound, growing louder every second, fell upon my attentive ears. This sound soon resolved itself into music ... and it was in the midst of a formidable “Hurrah! Long live France!” shouted by ten thousand throats, strengthened by an orchestra playing the “Marseillaise” with a frenzied fury, that we made our entry into Montreal.

The place where the train stopped in those days was very narrow. A somewhat high bank served as a rampart for the slight platform of the station.

Standing on the small step of my carriage, I looked with emotion upon the strange spectacle I had before me. The bank was packed with bears holding lanterns. There were hundreds and hundreds of them. In the narrow space between the bank and the train which had come to a stop, there were more bears, large and small ... and I wondered with terror how I should manage to reach my sleigh.

Jarrett and Abbey caused the crowd to make way and I got out. But a deputy whose name I cannot make out in my notes (what commendation for my writing!)—a deputy advanced toward me and handed me an address signed by the notabilities of the city. I returned thanks as best I could, and took the magnificent bouquet of flowers that was tendered in the name of the signatories to the address. When I lifted the flowers to my face in order to smell them, I hurt myself slightly with their pretty petals frozen by the cold.

However, I began to feel both arms and legs were getting benumbed. The cold crept over my whole body. That night, it appears, was one of the coldest that had been experienced for many years past.

The women who had come to be present at the arrival of the French company had been compelled to withdraw into the interior of the station, with the exception of Mrs. Joseph Doutre, who handed me a bouquet of rare flowers and gave me a kiss. It was twenty-two degrees below zero. I whispered low to Jarrett:

“Let us continue our journey, I am turning into ice. In ten minutes I shall not be able to move a step.”

Jarrett repeated my words to Abbey who applied to the chief of police. The latter gave orders in English and another police officer repeated them in French. And we were able to proceed for a few yards. But the station was still some way off. The crowd grew bigger, and at one time I felt as though I were about to faint. I took courage, however, holding or rather hanging on to the arms of Jarrett and Abbey. Every minute I thought I should fall, for the platform was covered with ice.

We were obliged, however, to stay further progress. A hundred lanterns, held aloft by a hundred students’ hands, suddenly lit up the place.

A tall young man separated himself from the group and came straight toward me holding a wide unrolled piece of paper, and in a loud voice exclaimed: “To Sarah Bernhardt....” And these are the lines he read:

A SARAH BERNHARDT

Salut, Sarah! salut, charmante Doña Sol!

Lorsque ton pied mignon vient fouler notre sol,

Notre sol tout couvert de givre,

Est-ce un frisson d’orgueil ou d’amour? je ne sais;

Mais nous sentons courir dans notre sang français,

Quelque chose qui nous enivre!

Femme vaillante au cœur saturé d’idéal,

Puisque tu n’as pas craint notre ciel boréal,

Ni redouté nos froids sévères,

Merci! De l’âpre hiver pour longtemps prisonniers,

Nous rêvons à ta vue aux rayons printaniers

Qui font fleurir les primevères!

Oui, c’est au doux printemps que tu nous fais rêver!

Oiseau des pays bleus, lorsque tu viens braver

L’horreur de nos saisons perfides,

Aux clairs rayonnements d’un chaud soleil de Mai,

Nous croyons voir, du fond d’un bosquet parfumé,

Surgir la reine des sylphides.

Mais non: de floréal ni du blond Messidor,

Tu n’est pas, ô Sarah, la fée aux ailes d’or

Qui vient répandre l’ambroisie,

Nous saluons en toi l’artiste radieux

Qui sut cueillir d’assaut dans le jardin des dieux

Toutes les fleurs de poésie!

Que sous ta main la toile anime son réseau;

Que le paron brillant vive sous ton ciseau,

Ou l’argile sous ton doigt rose;

Que sur la scène, au bruit délirant des bravos,

En types toujours vrais, quoique toujours nouveaux,

Ton talent se métamorphose;

Soit que, peintre admirable ou sculpteur souverain,

Toi-même oses ravir la muse au front serein,

A te sourire toujours prêtée!

Soit qu’aux mille vivate de la foule à genoux,

Des grands maîtres anciens ou modernes, pour nous

Ta voix se fasse l’interprète;

Des bords de la Tamise aux bords du Saint-Laurent,

Qu’il soit enfant du peuple ou brille au premier rang,

Laissant glapir la calomnie,

Tour à tour par ton œuvre et ta grâce enchanté

Chacun courbe le front devant la majesté

De ton universel génie!

Salut donc, ô Sarah! salut, ô Doña Sol!

Lorsque ton pied mignon vient fouler notre sol,

Te montrer de l’indifférence

Serait à notre sang nous-mêmes faire affront;

Car l’étoile qui luit la plus belle à ton front,

C’est encore celle de la France!

He read very well, it is true, but those lines, read with a temperature of twenty-two degrees of cold, to a poor woman dumfounded through listening to a frenzied “Marseillaise,” stunned by the mad hurrahs from ten thousand throats delirious with patriotic fervor, were more than my strength could bear, made me feel dizzy, and caused my head to reel.

I made superhuman efforts at resistance, but was overwhelmed with fatigue. Everything appeared to be turning round in a mad farandole. I felt myself raised from the ground and heard a voice which seemed to come from far away—“Make room for our French lady....” Then I heard nothing further and only recovered my senses in my room at the Hotel Windsor.

My sister Jeanne had become separated from me by the movement of the crowd. But the poet Fréchette, a French-Canadian, became her escort and brought her several minutes after, safe and sound, but trembling on my account, and this is what she told me—“Just imagine. When the crowd was pressing against you, seized with terror on seeing your head fall back with closed eyes on to Abbey’s shoulder, I shouted out ‘Help. My sister is being killed.’ I had become mad. A man of enormous size who had followed us for a long time worked his elbows and hips to make the enthusiastic but overwrought mob give way, with a quick movement placed himself before you, just in time to prevent you from falling. The man, whose face I could not see on account of its being hidden beneath a fur cap, the ear flaps of which covered almost his entire face, raised you up as though you had been a flower, and held forth to the crowd in English. I did not understand anything he said, but the Canadians were struck with it, for the pushing ceased, and the crowd separated into two compact files in order to let you pass through. I can assure you that it made me feel quite impressed to see you so slender, with your head back and the whole of your poor frame borne at arms’ length by that Hercules. I followed as fast as I could, but having caught my foot in the flounce of my skirt I had to stop for a second, and that second was enough to separate us completely.

“The crowd having closed up after your passage, formed an impenetrable barrier. I can assure you, dear sister, that I felt anything but at ease, and it was Mr. Fréchette who saved me.”

I shook the hand of that worthy gentleman and thanked him this time as well as I could for his fine poem, then I spoke to him of his other poems, a volume of which I had obtained at New York, for, alas! to my shame I must acknowledge it, I knew nothing about Fréchette up to the time of my departure from France, and yet he was already known a little in Paris.

He was very touched with the several lines I dwelt upon as the finest of his work. He thanked me for doing so. We remained friends.

The day following, nine o’clock had hardly struck, when a card was sent up to me on which were written these words: “He who had the joy of saving you, madame, begs that your kindness will grant him a moment’s interview.” I directed that the man be shown into the drawing-room, and after notifying Jarrett, went to waken my sister. “Come with me,” I said. She slipped on a Chinese dressing gown and we went in the direction of the huge, immense drawing-room of my apartment, for a bicycle would have been necessary to traverse my rooms, drawing-rooms and dining-room, for the whole length without fatigue. On opening the door I was struck with the beauty of the man who was before me. He was very tall, with wide shoulders, small head, a hard look, hair thick and curly, tanned complexion. The man was fine looking but seemed uneasy. He blushed slightly on seeing me. I expressed my gratitude and asked to be excused for my foolish weakness. I received joyfully the bouquet of violets he handed me. On taking leave he said in a low tone: “If ever you hear who I am, swear that you will only think of the slight service I have rendered you.” At that moment Jarrett entered with white face. He went up to the stranger and spoke to him in English. I could, however, catch the words: “detective ... door ... assassination ... impossibility ... New Orleans....”

His sunburnt complexion became chalky, his nostrils quivered as he looked toward the door. Then, as flight appeared impossible, he looked at Jarrett and in a peremptory tone, as cold as flint, said “Well” as he went toward the door. My hands, which had opened under the stupor, let fall his bouquet which he picked up, looking at me with a supplicating and appealing air. I understood and said to him in a loud tone of voice, “I swear to it, monsieur.” The man disappeared with his flowers. I heard the uproar of people behind the door, and of the crowd in the street. I did not wish to listen to anything further.

When my sister, of a romantic and foolish turn of mind, wished to tell me about the horrible thing, I closed my ears.

Four months afterwards, when an attempt was made to read aloud to me an account of his death by hanging I refused to hear anything about it. And now after twenty-six years have passed and I know, I only wish to remember the service rendered and my pledged word. This incident left me somewhat sad. The anger of the Bishop of Montreal was necessary to enable me to regain my good humor. That prelate, after holding forth in the pulpit against the immorality of French literature, forbade his flock to go to the theater. His charge was violent and spiteful against modern France. As to Scribe’s play, “Adrienne Lecouvreur,” he tore it into shreds, as it were, disclaiming against the immoral love of the comedienne and of the hero and against the adulterous love of the Princess of Bouillon. But the truth showed itself in spite of all, and he cried out with fury intensified by outrage—“In this infamous lucubration there are French authors, a court abbé who, thanks to the unbounded licentiousness of his expressions, constitutes a direct insult to the clergy.” Finally, he pronounced an anathema against Scribe, who was already dead, against Legouvé, against me, and against all my company. The result was that crowds came from everywhere, and the four presentations, “Adrienne Lecouvreur,” “Froufrou,” “La Dame aux Camélias” (afternoon performance), and “Hernani,” had a colossal success and brought in fabulous receipts.

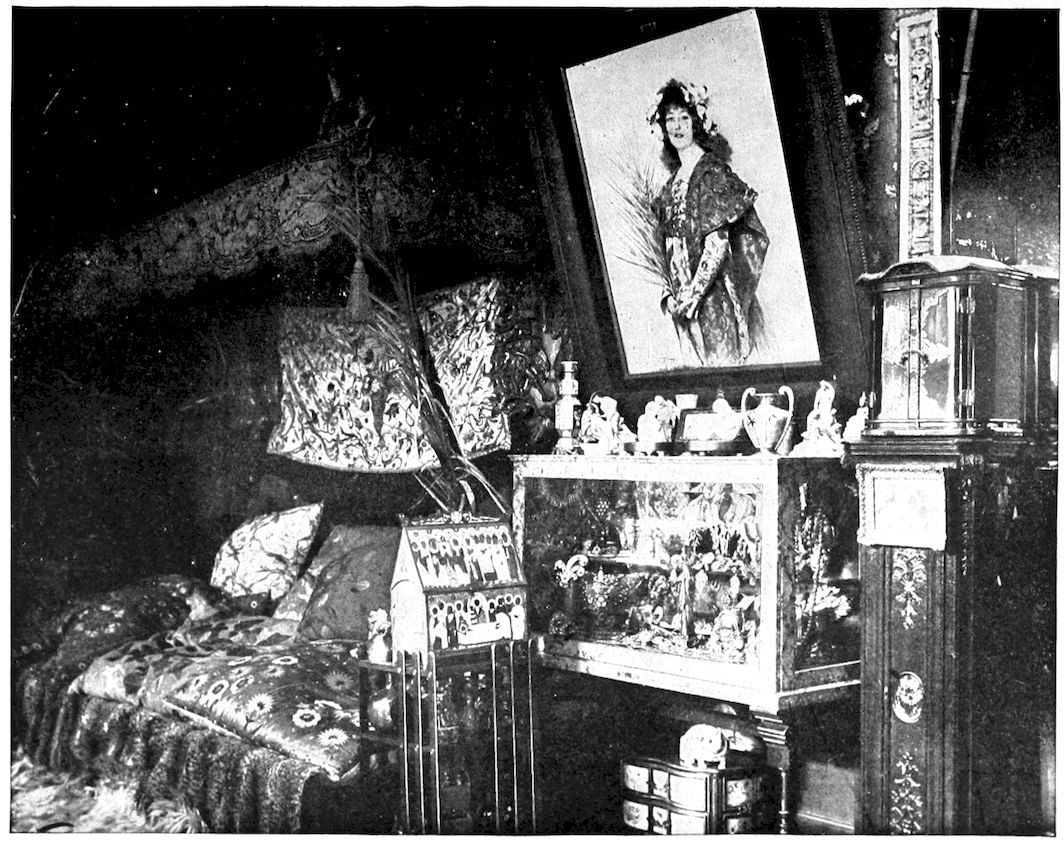

CORNER IN SARAH BERNHARDT’S PARIS HOME, SHOWING PORTRAIT BY CHARTRAN.

I was invited by the poet Fréchette and a banker whose name I do not remember to make a visit to Ottawa. I accepted with joy, and went there accompanied by my sister, Jarrett, and Angelo, who was always ready for a dangerous excursion; I felt in safety in the presence of that artist, full of bravery and composure, and gifted with herculean strength. The only thing he lacked to make him perfect was talent. He had none then and never did have any.

The St. Lawrence River was frozen over almost entirely; we crossed it in a carriage along a route indicated on the river by two rows of branches fixed in the ice. We had four carriages; the distance between Ottawa and Montreal is one hundred and twenty-five kilometers.

This visit to the Iroquois was deliciously enchanting. I was introduced to the chief, father, and mayor of the Iroquois tribes. Alas! this former chief, son of “Big White Eagle,” surnamed during his childhood “Sun of the Nights,” now clothed in sorry European rags, was selling liquor, thread, needles, flax, pork fat, chocolate, etc. All that remained of his mad rovings through the old wild forests—when he roamed naked over a land free of all allegiance—was the stupor of the bull held prisoner by the horns. It is true he also sold brandy and that he quenched his thirst, as did all of them, at that source of forgetfulness.

“Sun of the Nights” introduced me to his daughter, a girl of eighteen to twenty years of age, insipid and devoid of beauty and grace. She sat down at the piano and played a tune that was popular at the time—I do not remember what. I was in a hurry to leave the store—the home of these two victims of civilization.

I visited Ottawa, but found no pleasure in it. The same compression of the throat, the same retrospective anguish caused me to revolt against man’s cowardice which hid under the name of civilization the most unjust and most protected of crimes.

I returned to Montreal somewhat sad and tired. The success of our four performances was extraordinary, but what gave them a special charm in my eyes was the infernal and joyous noise made by the students. The doors of the theater were opened every day one hour in advance for them. They then arranged matters to suit themselves. Most of them were gifted with magnificent voices. They separated into groups according to the requirements of the songs they wished to sing. Then they prepared by means of a strong string worked by a pulley the aërial route that was to be followed by the flower-bedecked baskets which descended from their paradise to where I was. They tied ribbons round the necks of doves bearing sonnets and wishes.

These flowers and birds were sent off during the “calls,” and by a happy disposition of the strings the flowers fell at my feet, the doves flew where their astonishment led them, and every evening these messages of grace and beauty were repeated. I experienced considerable emotion the first evening. The Marquis of Lorne, son-in-law of Queen Victoria, Governor of Canada, was of royal punctuality. The students knew it. The house was noisy and quivering. Through an opening in the curtain I gazed on the composition of this assembly. All of a sudden a silence came over it without any outward reason for it, and the “Marseillaise” was sung by three hundred warm, young, male voices. With a courtesy full of grandeur the governor stood up at the first notes of our national hymn. The whole house was on its feet in a second, and the magnificent anthem echoed in our hearts like a call from the mother country. I do not believe I ever heard the “Marseillaise” sung with keener emotion and unanimity. As soon as it was over, the plaudits of the crowd broke out three times over, then, upon a sharp gesture from the governor, the band played “God Save the Queen.”

I never saw a prouder and more dignified gesture than that of the governor when he motioned to the leader of the band. He was quite willing to allow these sons of submissive Frenchmen to feel a regret, perhaps even a flickering hope. The first on his feet, he listened to that fine plaint with respect, but he smothered its last echo beneath the English national anthem. Being English, he was incontestably right in doing so.

I gave for the last performance, on the 25th December, Christmas Day, “Hernani.”

The Bishop of Montreal again thundered against me, against Scribe and Legouvé, and the poor artistes who had come with me who could not help it. I do not know whether he did not even threaten to excommunicate all of us, living and dead. Lovers of France and French art, in order to reply to his abusive attack, unyoked my horses, and my sleigh was almost carried by an immense crowd among which were the deputies and notabilities of the city.

One has only to consult the daily papers of that period to realize the crushing effect caused by such a triumphant return to my hotel.

The day following, Sunday, I left the hotel at seven o’clock in the morning with Jarrett and my sister, for a promenade on the banks of the St. Lawrence River. At a given moment I ordered the carriage to stop with the object of walking a little way.

My sister laughingly said, “What if we climb on to the large piece of ice that seems ready to crack?” No sooner thought of than done. And behold, both of us walking on the ice trying to break it loose. All of a sudden, a loud shout from Jarrett made us understand that we had succeeded. As a matter of fact, our ice bark was already floating free in the narrow channel of the river that remained always open through the force of the current. My sister and I sat down, for the piece of ice rocked about in every direction, making both of us laugh inordinately. Jarrett’s cries caused people to gather. Men armed with boat hooks endeavored to stop our progress, but it was not easy, for the edges of the channel were too friable to bear the weight of a man. Ropes were thrown out to us. We caught hold of one of them with our four hands, but the sudden pull of the men in drawing us toward them cast our raft so suddenly against the icy edges that it broke in two, and we remained, full of fear this time, on one small part of our skiff. I laughed no longer, for we were beginning to travel somewhat fast, and the channel was opening out in width. But in one of the turns it made, we were fortunately squeezed in between two immense blocks, and to this fact we owed being able to escape with our lives. The men who bad followed our very rapid ride with real courage, climbed on to the blocks. A harpoon was thrown with marvelous skill on to our icy wreck so as to retain us in our position, for the current, rather strong underneath, might have caused us to move. A ladder was brought and planted against one of the large blocks, and its steps afforded us means of delivery. My sister was the first to climb up and I followed, somewhat ashamed at our ridiculous escapade.

During the length of time required to regain the bank, the carriage, with Jarrett in it, was able to rejoin us. He was pallid, not from fear of the danger I had undergone, but at the idea that if I died the tour would come to an end. He said to me quite seriously, “If you had lost your life, madam, you would have been dishonest, for you would have broken your contract of your own free will.”

We had just enough time to get to the station where the train was ready to take me to Springfield.

An immense crowd was waiting and it was with the same cry of love, underlined with au-revoirs, that the Canadian public wished us good-by.