3 Moving towards maturity in business model definitions

(Written by Christian Nielsen, Associate professor, PhD, and Per Nikolaj Bukh, Professor, PhD)

[Please quote this chapter as: Nielsen, C. & P.N. Bukh (2012), Moving towards maturity in business model definitions, in Nielsen, C. & M. Lund (Eds.) Business Models: Networking, Innovating and Globalizing, Vol. 1, No. 2. Copenhagen: BookBoon.com/Ventus Publishing Aps]

The field of business models has, as is the case with all emerging fields of practice, slowly matured through the development of frameworks, models, concepts and ideas over the last 15 years. New concepts, theories and models typical y transcend a series of maturity phases. For the concept of Business Models, we are at the verge of moving from phase 2 to 3, after having spent a lot of time during the 1990’s and 2000’s arguing for the importance of understanding business models properly and discussing the content and potential building blocks of them. Therefore, in terms of maturity – the time for focusing on the more complex and dynamic aspects of business models seems to be right – right now!

Figure 6: The concept maturity line

In figure 6 above, the move from phase 2 to 3 significantly heightens the requirements for methodological coherence and structure and therefore it is also time to converge otherwise separate research streams and attempt to attain a common appreciation of business models. In the wake of this, a number of “business model associations” have emerged in recent years, e.g. around Osterwalder and Pigneur’s Business Model Canvas on www.businessmodelgeneration.com and www.businessmodeyou.com. There is also an assembly on non-coupled researchers and practitioners on www.businessmodelcommunity.com.

In an attempt to move the field into new ground 2011 saw the launching of the “Center for Research Excellence in Business modelS” (CREBS) as an interdisciplinary coordination hub for researchers and common research projects. CREBS’ aim is to function as a natural hub between the technology-based research environments and the business oriented research environments, thereby conforming interests from different environments. CREBS is therefore a natural partner for coordinating interdisciplinary research projects.

CREBS is primarily a project-based research center with affiliates from numerous professional and geographical backgrounds and interests. This is seen as a key strength, and for CREBS to be able to undertake large scale research projects, it relies to a large extent on ad hoc affiliations leveraged from the existing network. In other words, CREBS leverages an asset-light business model for business model research!

This debate on attaining maturity is important for the field in the sense that this will be a prerequisite for it to become accepted as a discipline in line with accounting, innovation, entrepreneurship, finance etc. In the remainder of this chapter we first discuss business model definitions from the perspective of different typologies, here relating to the breadth and scope of the suggested frameworks. After this we discuss the characteristics of business models as seen in the early literature. By characteristics we do not mean building blocks per se, rather the idea is to discuss the roles and affiliations of the business model and how different contributions seek to place the business model in the context of other fields of practice.

3.1 Business model typologies

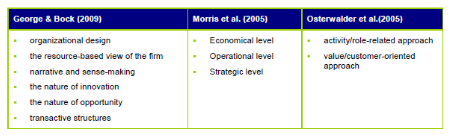

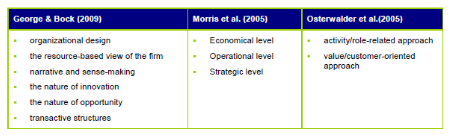

A substantial amount of literature is available on business models, including the components making up a business model (cf. Taran 2011) and frameworks of business models (Osterwalder et al. 2010), and still there seems to be a general consensus that no precise definition of a business model exists. According to Porter back in 2001 the definition of a business model was murky at best. Therefore, the theoretical grounding of most such business model definitions is still quite fragile despite the fact that at the present a substantial amount of literature is available on business models, including components, frameworks definitions etc. The aim of this chapter is to give an overview of existing definitions of a business model, and to provide frameworks for understandings of business models that are found in the literature. Fielt (2011) compares and categorizes a number of business model definitions below:

Figure 7: Categorizations of business model definitions (Fielt 2011)

According to Osterwalder et al. 2004, a business model is a conceptual tool that contains “a set of elements and their relationships and allows expressing a company’s logic of earning money. It is a description of the value a company offers to one or several segments of customers and the architecture of the firm and its network of partners for creating, marketing and delivering this value and relationship capital, in order to generate profitable and sustainable revenue stream’”. In this sense Osterwalder et al. here acknowledge that a business model to some extent becomes a mediating mechanism between the inside and the outside of the company.

Business model definitions and frameworks vary significantly according to whether they factor in outside relationships. Although the review here is structured around three types of perceptions of business models, these can only become crude classifications, as a great deal of overlap exists between business models and other concepts such as value chains and strategy. Thus, a clear interpretation of the boundaries of the review is a matter of interpretation. Here we have chosen to classify business model frameworks according to whether they concern generic descriptions of the business or whether they are more specific in their descriptions. The later category is divided according to whether the definitions solely consider elements inside the company (narrow) or also consider elements outside (broad).

The term generic business models, includes suggestions and definitions concentrating mainly on the elements such models ought to be comprised of in order to qualify as business models. On one hand this will provide an indication of which elements that could be considered necessary for the description of value creation from a business perspective, and on the other hand help differentiate business models from other related concepts and research areas such as supply chain management and organizational theory in general.

Next we focus on specific business models that are characterized by being more detailed than the generic business models, most often incorporating suggestions for specific elements or linkages; and often stating some kind of causality between the elements such as: activities, departments, processes or other. In the review we distinguish between broad specific business models that comprise focus on the whole enterprise system, including how the firm is positioned according to its partners in the value constel ation, and narrow specific business models that focus on the specific, often causal, links between organizational activities, processes and the likes, and which do not consider external aspects.

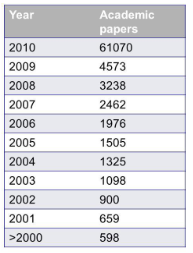

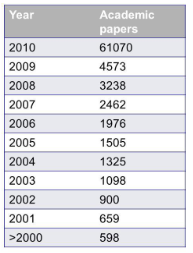

It must also be admitted that the amount of literature referring to the business model concept has been almost exploding within the few years, so an exhaustive review is difficult. Figure 8 below il ustrates this graphical y, as the development in the number of published academic articles containing the term “business model” is depicted. Both of the article databases Ingenta and Emerald contain similar trends, starting from almost none in the mid-1990’s to experiencing solid increases around the year 2000 and an explosion after 2005.

Figure 8: Application of the term business model.

3.1.1 Generic business model definitions

Traditional y, business models have been associated with industry models, where certain factors are likely to improve the chance of success for an organization almost in such a way that “[t]he name of the industry served as shorthand for the prevailing business model’s approach to market structure, organizational design, capital expenditures, and asset management” as Sandberg (2002, 3) provocatively states. This is for instance seen in the airline industry, where Hansson et al. (2002) il ustrate how the traditional airline companies currently find themselves in a competitive situation where they must change their business models in order to remain profitable, and the pharmaceutical industry where Burcham (2000) accentuates that companies must acknowledge that information technology is changing not only their business models but the entire pharmaceutical value chain. Thus, from this perspective, the business model relates to general industry attributes. These industry attributes are at the same time determinative with respect to common organizational aspects, i.e. which components that constitute a profitable business in the respective sectors.

The weakness of an approach focussing mainly on industries is that changes, e.g. new technologies, often give rise to a new or updated version of the traditional business model.

Although of course there is a certain stability in the ways of doing business within specific industries, and despite the fact that industry structure to a great degree dictates which business models become profitable, our aim here is to move beyond a mere listing of industry types and associated business models. In the context of so-called highly turbulent and competitive business environments, Chaharbaghi et al. (2003) identify three interrelated strands which form the basis of a meta-model for business models: characteristics of the way of thinking in a company, its operational system, and capacity for value generation. Although being very general notions, three elements are expressible in more concrete terms. For instance, the characteristics of the way of thinking in a company essential y pertain to a strategic conception, while capacity for value generation is very much in line with a resource-based perspective. Final y, the element ‘operational system’ hints to the inclusion of processes and a value chain perspective.

Hedman & Kalling (2003) propose that a generic business model is composed of the causal y related components: customers, competitors, the company offering (generic strategy), activities and organisation (including the value chain), resources (human, physical and organisational), and factor and production inputs. These notions are very much in line with Porter’s (1991) causality chain model, which can be considered an account of a business model. Somewhat related to Porter’s ideas are the recent suggestions relating to causal modelling of the service-profit-chain (Heskett et al. 1994) as a kind of general business model for the service sector.

Basing his ideas on the service management literature from the 1980’s, Normann (2001) distinguishes between three different components of a generic business model: The external environment, the offering of the company and the internal factors such as organisational structure, resources, knowledge and capabilities. The first component is the external environment, its needs and what it is valuing. These characteristics are in turn prerequisites for the offering of the company, which is the second component. Final y we have internal factors such as organisational structure, resources, knowledge and capabilities, equipment, systems, leadership, and values which are necessary for the company to deliver its offering. In comparison to Hedman & Kalling, Normann goes one step further by implicating that the concept is systemic in nature, and that the relationship to the external environment depends on the offering, which in turn is dependent upon firm-internal factors.

In this manner, the generic typology constitutes a meta model or ontology for business models. According to Chaharbaghi et al. (2003), there are three interrelated strands forming the basis of such a meta-model for business models: characteristics of the way of thinking in the company, its operational system, and capacity for value generation. For instance, the characteristics of the way of thinking in the company essential y pertain to a strategic conception, while capacity for value generation is very much in line with a resource-based perspective.

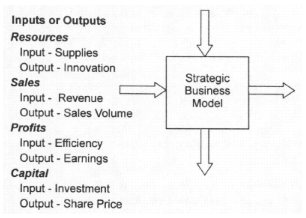

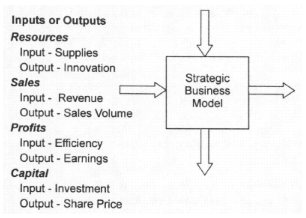

Another terminology is chosen by Osterwalder & Pigneur (2003), who propose a business model ‘ontology’ which consists of four main pil ars: product innovation, customer relationships, infrastructure management, and financial aspects. These can be further decomposed into their elements. This definition is very similar to the ideas spawned from Kraemer et al. ’s study (1999), where the four building blocks of Del ’s business model are identified as direct sales, direct customer relationships, customer segmentation for sales and service, and build-to-order production, as is also confirmed by Alt & Zimmermann (2001), who distinguish between six generic elements of a business model. The first three elements of Alt & Zimmermann’s suggestion are recognizable: mission (including vision, strategic goals and value proposition), structure (value chain), and processes (activities, value creation processes). However, the latter three elements: revenues (bottom line), legal issues (e.g. regulation), and technology (impact on business model design) are new in this context. Betz (2002) also acknowledges the element of linking the various ideas of value offering, value creation etc. to the bottom line. He argues for the construction of a generic business model incorporating the four elements: resources, sales, profits and capital (See figure 9).

Figure 9: Constructing a generic business model (Betz 2002, 22)

As can be seen from this brief review of the kind of business models that we here term generic business models, the characteristics are quite similar. However, the characteristics focussed on in the generic business models are, as could be expected, rather general and often encompassing the whole enterprise or value creating system (chain, network etc.).

3.1.2 Broad business model definitions

The first category of the specific business model definitions, i.e. business models that incorporate more precise suggestions with respect to the elements and linkages that enable value creation, is termed “broad” business models. In our terminology, this means that their focus is on the whole enterprise system, including how the firm is positioned according to its partners in the value constel ation. As a general characteristic the broad models typical y take a value chain perspective and include relationships to suppliers and customers while also taking external forces into account. Thereby in a sense also the concept of strategy.

A typical example of a broad business model understanding is Lev’s (2001, 110) company ‘fundamentals’. Drawing attention to Tasker’s (1998) analysis of technology company conference cal s, Lev emphasizes that the “information most relevant to decision making in the current economic environment concern the value chain of the enterprise (business model, in analysts’ parlance)” (Lev 2001, 110; original emphasized).

However, Lev’s definition of a business model takes its point of departure in Porter’s (1985) classical notion of the value chain. Particularly, Lev states that by value chain he means “The fundamental economic process of innovation […]that starts with the discovery of new products or services or processes […] and culminates in the commercialization” (Lev 2001, 110). In a sense, this is a description of the architecture of the company for generating value, a notion quite similar to Afuah & Tucci (2000, 2) designating that a business model describes “how [the firm] plans to make money long-term”.

According to Timmers (1998), a business model should be seen as “the architecture for the product, service and information flows, including a description of the various business actors and their roles; a description of the potential benefits for the various business actors; and a description of the sources of revenues.” Timmers’ definition is not very detailed and could probably also be categorized as a generic business model as the ones in the previous section. However, as it includes notions of visualizing how the business functions and a focus on the offering from the company to its customers, it relates as so more to the specific definitions.

A similar definition, in that it also has a focus on representation and value proposition is suggested by Weill & Vitale’s (2001) who define a business model as, “a description of the roles and relationships among a firm’s consumers, customers, allies and suppliers that identifies the major flows of product, information, and money, and the major benefits to participants”. This too is a very broad definition, in essence covering all possible aspects of doing business.

A number of the definitions within this category have explicit reference to the term sustainable development. Sustainable development is in essence, the ability of the company to create revenue in the long-term, especial y with consideration to the external stakeholders interests. Thus, there is a weak linkage to the generic definitions that often focuse more narrowly on profits and revenue, implicitly meaning a shorter term perspective.

Further, this way of conceptualizing the business model focuses on describing the method of doing business in a specific company. This is also in accordance with KPMG’s definition of a business model as “The fundamental logic by which the enterprise creates sustained economic value – the organizations “business model” (KPMG 2001, 3, 11). The terms ‘fundamental logic’ and ‘value configuration’ resemble Stabell & Fjeldstad’s value configuration logics (1998), and again these definitions cover all possible aspects of doing business.

Similarly, Rappa’s definition (2001) states that “a business model is the method of doing business by which a company can sustain itself – that is, generate revenue. The business model spel s-out how a company makes money by specifying its position in the value chain.” As well as departing in the notion of sustainable development, it also incorporates a more specific notion of the position of the firm in the value chain.

Another suggestion that we will pay special attention to, is offered by Chesbrough & Rosenbloom (2002), who sees the business model as integrating a series of perspectives including strategy (Seddon et al. 2004), management (Magretta 2002b), innovation (Gaarder 2003), and e-business enabled distribution models among others, into “a coherent framework that takes technological characteristics and potentials as inputs, and converts them through customers and markets into economic outputs. The business model is thus conceived as a focusing device that mediates between technology development and economic value creation” (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom 2002, 5).

Although this understanding is developed specifical y in relation to evidence from Xerox Corporations spin-off companies, the insights provided have a broader application and the authors also explicitly acknowledge “that firms need to understand the cognitive role of the business model, in order to commercialize technology in ways that will allow firms to capture value from their technology investments” (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom (2002, 5). The six components are discussed in greater detail in chapter 1.

These elements are representative for many authors’ view on business models. According to Marrs & Mundt (2001), a business model is designed to compile, integrate, and convey information about the business and industry of an organization. Further, in the context of the so-called Strategic-Systems Auditing framework, Bell et al. (1997) identified six components of a business model: external forces, markets/formats, business processes, alliances, core products and services, and customers. In essence this framework focuses on describing “the interlinking activities carried out within a business entity, the external forces that bear upon the entity and the business relationships with persons and other organizations outside of the entity” (Bell et al. 1997, pp. 37-39).

Later Bell et al. (2002) developed these ideas in the direction of a value driver focus which is one of the characteristics dealt with in the next section. The notion of describing links and activities and processes is likewise emphasized by Weill & Vitale (2001), who define a business model as, “a description of the roles and relationships among a firm’s consumers, customers, allies and suppliers that identifies the major flows of product, information, and money, and the major benefits to participants”.

In comparison to the generic typology of business models, this broad specific understanding comes closer to treating ‘how’ the relationships are than merely ‘what’ objects should be included. Furthermore, the broad business models act as representation of the central roles and relationships of the firm, whereas the generic definitions were more focused on resources necessary for value creation.

3.1.3 Narrow business model definitions

In comparison to the category above, the narrow business model definitions are characterized by focusing only on internal aspects of the organization. As exponents of this view of the business model, Petrovic et al. (2001) argue that a business model ought not to be a description of a complex social system with all its actors, relations and processes, like the broad definitions imply. Instead, they contend, it should describe the value creating logic of a company (see also Linder & Cantrell 2002), the processes that enable this, i.e. the infrastructure for generating value, and constitute the foundation for conceptualizing the business strategy.

Similarly, Boulton et al. (2000) emphasize the need to create a business model that links combinations of assets to value creation. Having defined a business model as “[t]he unique combination of tangible and intangible assets that drives the ability of an organization to create or destroy value” (Boulton et al. 1997, 244), these authors’ definitions can be seen as a detailed account of the internal prerequisites for value creation. Their focus on key measures of the value creation process, i.e. the value drivers, shows the uniqueness of internal aspects.

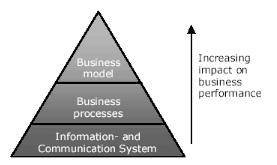

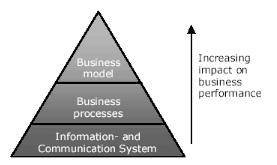

Figure 10: Hierarchical structure of business logic (Petrovic et al. 2001, 2)

Even more focused on value drivers and processes is Bray’s view where “The business model is defined by the performance drivers, business processes, people and the infrastructure put in place to achieve the company’s business objectives” (2002, 13). Bray’s explicit link to business objectives is at the same a link to strategy and – especial y – value creation, although this is not specifical y stated. Value creation is, however, somewhat more explicitly mentioned in Linder & Cantrel ’s business model definition: “A real business model is the organization’s core logic for creating value” (2002) as it more specifical y

- The set of value propositions an organization offers to its stakeholders,

- Along with the operating processes to deliver on these,

- Arranged as a coherent system,

- That both relies on and builds assets, capabilities and relationships in order to create value.

Another central tool when describing a company’s value creation story is to support narratives with non– financial performance measures. One thing is to state that oneś business model is based on mobilizing customer feedback in the innovation process, another thing is to explain by what means this will be done, and even more demanding is proving the effort by indicating: 1) how many resources the company devotes to this effort; 2) how active the company is in this matter, and whether it stays as focussed on the matter as initial y announced; and 3) whether the effort has had any effect, e.g. on customer satisfaction, innovation output etc. According to Bray (2010, 6), “relevant KPIs measure progress towards the desired strategic outcomes and the performance of the business model. They comprise a balance of financial and non-financial measures across the whole business model.”.

From this we can deduct that the business model should explain how the organization offers unique value, be hard to imitate, be grounded in reality (economics), and can help to ensure that different stakeholders are speaking the same language.

Competitive strategy is about being different, and the business model in this respect is the vehicle for operationalizing such differences. Thus, a well-constructed business model facilitates an understanding of the activities that real y add value. A business model is thus an account of the links, processes, and networks of causes and effects that create value. Sandberg 2002 argues that a business model must identify the customers you want to serve, spell out how your business is different from all the others—its unique value proposition, explain how you will implement the value proposition, and final y also describe the profit patterns, the associated cash flows, and the attendant risks within the company.

In summary, the narrow definitions predominately focus on details regarding the internal prerequisites for profitability and business models as systems of representation. Some of the suggestions found in the literature also incorporate elements of value proposition and uniqueness. To conclude on this review of the different types of business model frameworks, the attributes of the three typologies of business model definitions along with possible strengths and weaknesses are listed in table 1 below.

Table 1: Attributes, strengths and weaknesses across the three typologies of business model definitions

3.2 Business model characteristics

The act of representing an object is equivalent to making it visible and thus manageable as when making activities auditable by representing accounting for them and when mechanisms are created to capture the essence of a phenomenon, e.g. in the representation of intellectual capital and value creation. Therefore, representation lies in the conception of the term business model itself. The business model – being a model of the business – is exactly such a representation, whether acknowledged explicitly or not. Focusing at the ‘level of organizations’, characterized by communication, interrelations, roles and division of labor etc., the system becomes as already Boulding (1956, 205) stated difficult to comprehend.

Simplifications needed because we as humans have limited cognitive abilities (Simon 1959). Representation is derivable as a question of how we transcribe the world around us for the sake of being able to comprehend it; in a sense perceiving representations as common-sense explanations of how objects are connected. Thus, we can perceive business models as representations of a business system where the specific business model in a company represents a choice between feasible alternatives (Chaharbaghi, Fendt & Willis, 2003) and essential y summarizes these choices that prepare the business to perform in the future (Betz 2002). Bell & Solomon (2002) enhance this perspective of the business model as a representation of the business system, in that it is a “simplified representation of the network of causes and effects that determine the extent to which the entity creates value”, thereby underlining the business models role in il uminating the critical value drivers of the company.

Among the underlying notions of representation are concerns of objectivity, power, and description vs. transformation. As we, in this context, are interested in understanding how management can grasp the organization, i.e. conceptualize it and manage it, objectivity becomes a question of representational faithfulness (cf. Napier 1993).

As the first characteristic within this group we find perceptions of business models where the business model is seen as a representation of the business. Representation has several objectives and not just the obvious one of enabling conceptualization by creating a simplistic model of reality. As accentuated by Bell & Solomon (2002), management’s ability to disperse their mental models through the organization and thereby create a common understanding of strategic direction, corporate culture etc. of the company is also a tool of power. This has some indications of a controlling-at-a-distance perspective (Cooper 1992). Chaharbaghi, Fendt & Willis (2003) accentuate this view and define business models as a representation of management thinking and practices that help businesses see, understand and run their activities in a distinct and specific way. Representation thus becomes a communicative tool in the sense of projection as the power to get ones projection out enables control from a distance.

When perceiving business models as simplified versions of reality, representation becomes an abstraction of the business, identifying how that business makes money. Business models are abstracts about how inputs to an organization are transformed to value-adding outputs (Betz 2002). Along these lines of thoughts, the business model functions as a construct (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom 2002), describing the relationships between the elements of the value creation system (Weill & Vitale 2001), il ustrating e.g. the architecture of product, service and information flows (Timmers 1998).

Secondly, from a narrative perspective business models can be a support mechanism for projection of management?