Aiden: Low Scorer

Mario pointed to the profile of Aiden, a new rep he had hired. Aiden had attractive skills and experience, but scored well below normal for recovery from setbacks. He currently had a low number of calls, and Mario was hoping that by training Aiden and providing other support, he would eventually perform at a much higher level.

“Aiden’s low score,” I said, “tells us he doesn’t cope well with rejection. Every rejection affects him, so he needs time to recover and likely puts off making the next call . You could try everything to motivate Aiden—you could train him, give him scripts to follow, and support him with software and systems—but none of those interventions will change who Aiden is.

“The relatively low score for this attribute reveals that Aiden is going to struggle in any role that demands quick recovery from setbacks, such as a role for which he has to call on people who are likely to reject him.” I looked at Mario and added, “I would also guess that Aiden isn’t very happy in his role.”

Mario nodded and told me that he’d been concerned about this, but had hoped he could turn things around for Aiden through training and motivating him.

Charlotte: High Scorer

For comparison, I pointed to Charlotte, one of Mario’s top reps, who scored well above the normal range for recovery from setbacks; in fact, it was the highest score on Mario’s team. Here’s a person who gets rejected and it doesn’t faze her. Charlotte doesn’t care about the nine out of ten people that reject her—she wants to get through those rejections as quickly as possible because she knows she’s getting closer to the one who will say yes.

“Yeah, and Charlotte loves her job. I definitely want more people like her,” Mario said. “But I like Aiden. I want him to succeed, but I can see that he has low scores for almost every single critical attribute.”

“Mario,” I said, “you can’t change who Aiden is. When people have their core attributes profiled ten years apart, their scores are almost identical. But what you can change for Aiden is the context. You might be able to move Aiden into a different type of role on your team, or perhaps on another team at your company where he is more likely to succeed. Or maybe the right job for Aiden is at another organization.”

Because Aiden was currently a new-business rep, I suggested to Mario that we compare the profile of Aiden’s core attributes to the success profile of the account-management role. When we did that, we discovered that Aiden’s profile matched Mario’s high-performing account managers.

Mario said, “I probably would have tried to move Aiden into account management in a few months, which is what I’ve been doing for most reps who don’t succeed in the new-business role. But I can see that I should probably do this now.”

Instant Access

“Mario,” I said, “you’ve been using time as your filter to discover who will succeed. But the WHY data isn’t dependent on time. Because it’s part of who we are, you can access that data anytime. It can reveal information about someone that would otherwise take you months to discover, or that you might never actually discover because it’s not really perceptible. By profiling everyone on your team, you can instantly see what roles they are built for. You can also profile every applicant to discover whether or not they possess the same attributes as your top performers.”

“One thing I’ve noticed,” Mario said, “is that whenever I adjust or change our sales strategy, sometimes different people on my team emerge as new top performers. When that happens, I could look at their WHY data and see what’s driving their performance, and then start looking for people who possess these same attributes.”

Critical Decisions

Over the next few weeks, Mario used the WHY data on his reps to make some key decisions. In some cases, he helped low performers whose profiles revealed they weren’t built for any roles on his team find opportunities elsewhere in the organization, where they eventually thrived. In other cases, he moved low performing reps, like Aiden, into different sales roles for which they had the success attributes.

Mario also began to profile every applicant to get their WHY data, which allowed him to see whether or not they possessed the attributes of his current top performers. He ended up hiring candidates he never would have considered before, including two people who had almost no prior sales experience. These were people he would have passed over before based on their resumes and their lack of history as high-performing sales reps. Within the next few months, however, these two hires would prove themselves to be among Mario’s top performers.

A Team Transformed

The decisions Mario made for his people—where to put them, who to let go, and who to hire—had a dramatic impact on the performance metrics of his team, and overall results. Within a couple quarters sales improved enough that the CEO let Mario continue rolling out his strategies.

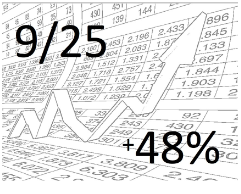

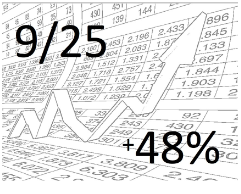

By the end of the year, nine out of twenty-five people were performing at or above the level of his previous top five performers. And the average performance of the rest of the team was close to 20 percent higher than the average prior to incorporating the WHY data. Perhaps most importantly, Mario’s team exceeded the revenue target, delivering an increase of 48 percent over the previous year.

A lot of that growth was driven simply by Mario’s ability to quickly identify and bring on four reps who matched the profiles of his top five reps, and who were able to deliver at the same level. Of course, raising the overall average contributed as well .

In the following two years, Mario’s team would continue to exceed the 25 percent revenue growth objective.

By the way, Aiden, the salesperson who had struggled as a new-business rep, became one of Mario’s top account managers. A proof point that Aiden is not a “high performer” or a “low performer”—we can’t define Aiden this way, but we can say Aiden is someone who performs well in the roles for which he is built. Mario was also thrilled to inform me that Aiden was happy in this new role—not surprising, considering that high performance and happiness have a tendency to go together.

Completing the Picture

When all we have is WHAT data, we tend to make the mistake of defining people by what they’ve done or what we see them do; we’ll label them “high performer” or “low performer.” And when we do that, we miss the truth about who they are. The WHY data completes the picture of somebody. It reveals the conditions they need to perform at their highest level, providing us with the information on how to best set them up for success.

and how they are built. Even when people have the right skills and experience, when they work in roles where the success profile isn’t a fit for who they are, they often perform at subpar levels. When they work in roles that suit their core attributes, they frequently perform at the highest levels.

Embrace the Power of WHY

I hope that after reading Mario’s story, I have inspired you to explore the power of WHY data. I have seen the number of leaders embracing WHY data grow from almost nothing to thousands. I believe that in the coming decades those thousands will turn into millions, and the world will be a better place for it—with happier employees and more productive organizations.