Chapter 6

Understand How Being Specific Can Make You A Better Communicator

One of the biggest issues in human communication is the lack of specificity – the existence of ambiguity, or non-specific communication. Because people are not specific in their communication with others, errors in the communication process occur. Almost all social communication is ambiguous to some degree.

When we communicate with others, we speak in terms of thoughts or ideas that are communicated through representational systems such as images, signs and symbols. The mind goes through a process in which those images, signs and symbols are constructed for each idea we wish to convey, however, in the communication process, we tend to omit certain details, and core concepts regarding those representations. This could be because communication of the core ideas requires us to search within ourselves for the specific ideas generated by the unconscious, and this requires additional time and effort, which may not be viewed as necessary or worthwhile under common circumstances.

The funniest thing happens when a lack of specificity exists: The receiver of the communication (the listener) will usually, rather than ask for clarification, simply replace the unknown with his own information or understanding of the representation. In simple terms, he will fill in the blanks (most likely out of fear of appearing stupid).

The problem is enhanced when lack of specificity becomes habit, or when all communication circumstances are viewed as equal, whether consciously or not. People tend to speak naturally in most circumstances, and do not normally pre-consider the words or sentences they choose.

Another reason for the lack of specificity is that people are inherently lazy. Our brains are designed to filter out what’s unimportant, and focus on what is important... and the deciding factor is usually based on an attempt to achieve more with less. Thus we aim to say only as much as we need to in order to get our point across.

# NOTE: Simply being aware of possible areas of misunderstanding can help make you a better communicator.

Syntactic & Semantic Ambiguity

Dr. Milton Erickson defined three main communication errors that result in a lack of specificity – Deletions, Distortion and Generalizations. But, before we get to that, let’s take a look at linguistic classes of ambiguity.

Syntactic Ambiguity

Syntactic ambiguity occurs when a sentence can be misinterpreted as having more than one meaning, mainly occurring from the relation of the words within the sentence.

Syntactic ambiguities most often occur because of the way that words are cross-referenced. Take a look at the following example:

“The woman played with the child in the green shirt.” (Is it the woman who is wearing the green, or the child who is wearing the green shirt?).

Consider another example:

“Yesterday I saw my wife with another man by the window.” (Who was by the window, myself, my wife, or the other man?)

Syntactic ambiguities can also occur because of the way that words are grouped together. Consider the following statement:

“Please give me the red and green balls.”

This may be understood as “Please give me the balls that are dual-colored – red and green” or it may be understood as “Please give me the red ball, and also the green ball” (using singular form) or it may also be understood as “Please hand me the red balls and the green balls (using plurals).

Consider how your phrases or sentences may be understood and/or misinterpreted by the receiver, and if necessary, rephrase your sentences so they may be better understood. You may add additional information, or repeat and rephrase the sentence altogether. Consider also asking for confirmation that your sentences have been understood by the receiver.

Semantic Ambiguity

Often referred to as lexical ambiguity, semantic ambiguity occurs when a sentence can be misinterpreted due to phonological error - When a word within a sentence can have two or more meanings, thus causing the entire sentence to appear ambiguous. The most common semantic ambiguities occur from the use of:

a) Homonyms: Words that are spelled the same and sound the same, but have different meaning. Example: “I saw her duck”. (Did she bend down to avoid being hit by something, or did she have a pet duck?).

b) Homophones: Words that are spelled differently but sound the same, and have different meaning. Example: “This edition is great!” which may be understood as a new version (edition) or an added element (addition).

“Rumack: Can you fly this plane, and land it?

Ted Striker: Surely you can't be serious.

Rumack: I am serious... and don't call me Shirley.”

- From the movie Airplane

Semantic ambiguity can also occur due to the use of slang or industry jargon. For example:

“The chopper flew right by us” (the word “chopper” is often used to refer to both a motorcycle and a helicopter. Note: that the word “flew” is also a semantic ambiguity and is often used to refer to flight, or in slang it refers to moving at a fast pace).

Semantic ambiguity can also occur due to the use of slang or industry jargon. For example:

“The chopper flew right by us” (the word “chopper” is often used to refer to both a motorcycle and a helicopter. Note: that the word “flew” is also a semantic ambiguity and is often used to refer to flight, or in slang it refers to moving at a fast pace).

Another example would be:

“I have to go to the can” (the term “can” could refer to a metal cylinder used to store drinks, or it could refer to a toilet).

Other semantic phonological ambiguities may occur within multiple words, compound words, or words that include a prefix or suffix… Consider for example the following: “Incapable hands”. Spoken aloud this may be understood as it is written, or it may be understood as “In capable hands”..

Another example would be the phrase:

“He’s seeing a psychotherapist” (Is he seeing a doctor who gets you to relax and discuss your problems while he listens? Or is he seeing a psycho therapist – a doctor who attempts to cure cases of insanity?)

# NOTE As with syntactic ambiguities, consider clarifying your language by adding additional information or rephrasing your sentences to ensure that you are well understood. With compound words and words that include a prefix or suffix, you may consider adding strategic pauses to ensure the listener does not misunderstand the break-up of words.

Synonymous Terminology

Very similar to syntactic ambiguity is the lack of common terminology. Much like earlier examples (“chopper”, “flew” and “can” as used in semantic ambiguity), other definitions may be used to describe a single noun or verb. The construction industry for example, uses the same word to describe a sheet of wood known as OSB (oriented strand board), which may also referred to as “particle board”, “sheathing” (such as wall sheathing), “sterling board”, “asperite”, or “smart ply”. This host of available terms used to describe one thing can often make it difficult to understand each other. Terminology may also be different in differing regions, cultures, or social classes.

# NOTE: While it is quite impossible for every person to memorize the entire thesaurus, it possible to apply greater effort to establishing a common term for words when questionable doubt arises.

# NOTE: When in doubt as to the meaning of words, rather than make assumptions, ask questions that begin with “Did you mean…?” or “Are you referring to…?” Don’t be afraid to let people know that you are not certain of their terminology.

Deletions

Deletion occurs when we leave out pieces of information. As we communicate, we naturally filter out pieces of information that are deemed irrelevant, unimportant (under the circumstance) or uninteresting, which are all subject to interpretation. This means that what may be irrelevant to you may not be to someone else.

Unspecified Nouns

Deletion occurs when we leave out pieces of information. As we communicate, we naturally filter out pieces of information that are deemed irrelevant, unimportant (under the circumstance) or uninteresting, which are all subject to interpretation. This means that what may be irrelevant to you may not be to someone else.

Unspecified Nouns

Nouns are “things” – people, places, objects etc. People will often speak of nouns without specifying or even considering the possible variances of that noun that exist. For example: You might buy a new car and simply state

“I’d like to buy a new car”.

# NOTE: This does not give any indication as to what kind of car you’d like to buy. It often leaves the listener to attempt to clarify the missing information.

# NOTE: Use sentences that aim to force the speaker into being more specific, such as sentences that begin with either “What specifically…” or “What type of _X_ specifically…”.

Unspecified Verbs

Verbs are words that denote action. People use verbs in broad terms, usually because they feel that additional information is unneeded. Take the sentence “he left the building” for example – This does not suggest why he left the building, or even how he left the building, but rather allows the missing information to be assumed by the listener (which may be assumed incorrectly).

“Doctor: "Captain, how soon can we land?"

Captain: "I can't tell."

Doctor: "You can tell me. I'm a doctor."

Captain: "No, I mean I'm just not sure."

Doctor: "Well, can't you take a guess?"

Captain: "Well, not for another two hours."

Doctor: "You can't take a guess for another two hours?"

Captain: "No, I mean we can't land for another two hours."

-- (From the movie, Airplane)”

# NOTE: Use questions that begin with “How specifically…” or “Why specifically…” to attain additional information.

Unspecified Adjectives

Adjectives are words that describe a noun – They describe size, shape, color, etc. Most adjectives used by people in our daily lives are unspecific. Take for example the following sentence fragments.

“The big dog was barking loudly.” (which big dog?)

“I like the blue car.” (what do you like about it?)

“That is a very fancy building.” (what is fancy about it?)

Most unspecified adjectives can be specified through the use of questions that begin with “What specifically…”, or by attending to the connected noun and using questions that begin with “specifically which...”

Pronouns

Pronouns are words that are used in place of some nouns. Pronouns are often used to refer to nouns, so that we do not have to constantly state the noun itself… Imagine a conversation where a noun was consistently repeated: “My house is small, my house is a cottage by the beach, and I have friends and family visit me at my house all the time”… The repetition of “my house” can appear quite annoying, thus we replace it with the pronouns “it” and “there”: My house is small, it is a cottage by the beach, and I have friends and family visit me there all the time”.

With the use of pronouns can arise several issues: The first is that they are often overused, and when this happens their meaning can become obscure – They should be used only to refer to nouns that have previously been mentioned (called a referential index) and/or it when is well understood which noun they refer to.

A second problem with pronouns is the misuse of them, meaning they can be placed incorrectly. Pronouns should refer to the noun that has most recently been mentioned. When a second noun is mentioned, it should first be described, and if referring to a previously mentioned noun it should be restated to ensure clarification. See the following example of misuse: “My mother and my sister went to the store, she purchased many things”. In this example, the word “she” should refer to my sister, as this would be the preceding noun. If it was intended to refer to “my mother”, then “my mother” should have been restated as follows: “My mother and my sister went to the store, my mother purchased many things”.

Finally, pronouns are sometimes used without any reference at all. This missing referential index can act similar to universal quantifiers (see below). An example of this would be “it is believed that humans evolved from apes” – This does not specify who believes this, and allows us to assume that everybody believes this (which would be a fallacy).

Woman: "You got a telegram from headquarters today."

Man: "Headquarters? What is it?"

Woman: "It's a big building where generals meet."

-- (From the movie,"Airplane")

While there are many types of pronouns, the following is a short list of the types of pronouns that require special attention when their meaning in unclear.

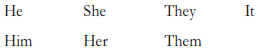

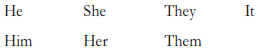

1) Personal Pronouns

Personal pronouns are used in place of personal nouns. They include:

# NOTE: When personal pronouns are used, and the referential index to which they belong is not clear, use phrases that begin with either “Who specifically…,” or in the case of the pronoun “it” use “What specifically…” .

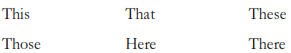

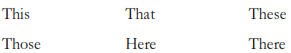

2) Demonstrative Pronouns

As the name implies, demonstrative pronouns are designed to demonstrate the existence of something. These include words such as:

# NOTE: When pronouns are used in an ambiguous manner, clarify the referential index by asking questions that begin with either “What specifically…” or “Where specifically…”

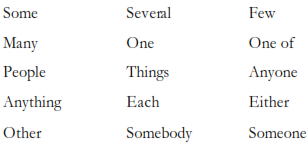

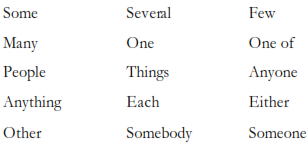

3) Indefinite Pronouns

The use of indefinite pronouns is a primary source of ambiguity due to being unspecific, and should be used with extreme caution. They include:

As example, a sentence such as “Some people believe the world is coming to an end soon” does not provide any indication as to how many people believe this… Essentially, any more than one can be considered “some”.

# NOTE: Use questions that begin with “What specifically…” or “Who specifically…”

Comparatives

Comparatives are words or word combinations that express a difference between two things, or compare two things. Comparatives are unspecific in that they do not tell to what degree the difference between two things exists.

There are four primary methods of recognizing comparatives, they are:

1) Use of the word(s) “than”, “more than” or “more… than”. An example of this could include: “This training is more in-depth than other similar training courses!”

2) Use of the word(s) “more” or “even more”. For example: “This will cost a little bit more”.

3) Use of the word(s) “less” “less than” or “less… than”

4) Use of words ending in “er”. For example, “This is a better one”.

When comparatives are used, consider seeking to specify them by questions that begin with "how specifically"; "specifically how much..." , or "exactly to what degree...".

Excessiveness

There are several adverbs that denote a degree of excessiveness – The most common of which being the word “too”. When we use the word “too” preceding an adjective (example: “too much” or “too little”) we are speaking in some form of excessiveness. In essence, "too" is a measurement word that does not directly provide measurement, and it is for this reason that it is considered ambiguous. It has become norm to use statements of excessiveness without providing any indication of specifics, and it is thus the listener’s responsibility to make an attempt to clarify the situation.

One method of clarifying such statements is to create a comparison. People often make judgments of one thing by comparing them to something else. Thus, the statement “It’s too expensive” may be resolved by “Compared to what?”, or other similar questions that seek comparison. Another method would be to directly question the statement by seeking a definition, thus the above statement “It’s too expensive” could be answered either with “How much is too expensive?” or by “How much are you willing to spend?”.

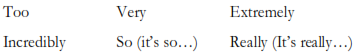

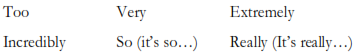

Below are a few words that denote excessiveness:

Illusion of Choice

An illusion of choice occurs when you are given a choice between two or more things (usually no more than two or three), but the choices offered do not extend to the full scope of choices available. This creates a limitation where there is no need for limitations.

Illusion of choice can be recognized through the use of the words “either” and “or”. For example: “Either A or B can be made available.” Another example using the word “or” would be “Would you like A or B.” (This is called an alternative choice question in sales).

Such statements or questions are designed to prevent consideration of additional choices. Maybe there is a choice C that we failed to look at. Maybe our options are completely open. Who knows?

# NOTE: Illusion of choice questions or statements are unspecific because they do not provide all the choices. When you recognize that someone has offered an illusion of choice question or statement, consider the context involved, and what additional options may be present.

Distortions

Distortion occurs in the way that we interpret information, both as the sender of the communication and as the receiver. Essentially, the facts become distorted to mean what we want them to mean, instead of what they truly are, this is highly influenced by such aspects as perception, presuppositions, and other means in which our brains recognizes what we see and hear.

Mind Reading

People often make assumptions about life in order to feel prepared for the future. Sometimes, we make assumptions about the thoughts and intentions of other people, and sometimes we do this without warranted proof. An attempt to make assumptions about the thoughts, feelings or intentions of others is called mind reading – We cannot really read the mind of others, but we sometimes think we can, and believe that our assumptions are the absolute truth.

Mind reading is apparent in statements such as the following, and the inherent thinking that is associated with these types of statements:

“I know what he’s thinking!”

“I know how you feel”

“I know what he’s going to do next”

# NOTE: Omit mind reading attempts in your own communication. When mind reading is communicated by others, seek clarification by asking questions such as “How do you know?” or “How can you be sure?”

Lost Performatives

A lost performative is when a statement is made about a personal belief, that is presented as an absolute or universal truth. Doing this allows the speaker to remove themselves from being directly associated with the statement. These statements often use generally accepted information, established assumptions or popular beliefs to add to their believability. The following are examples of lost performatives:

“Vitamins are an essential part of any diet.”

“You have to dress well to be successful.”

“You can’t be a good communicator if you don’t learn this.”

# NOTE: Lost performatives should be questioned to seek reason or authority such as “Why would you say…” or “According to who”

Cause & Effect Statements

Cause and effect statement are used to indicate how one thing leads to another. People often make such statements without directly questioning how or why one thing leads to another - When asked how A leads to B, people may not be able to provide a direct answer.

Examples of cause and effect statements may include:

“It makes me angry when he says stupid things.” (Why does that make you angry?).

“If you eat healthy you’ll lose weight.” (Does this apply to everybody?).

“Bad judgments cause bad behavior.” (Is there anything else that causes bad behavior?).

# NOTE: Cause and effect statements are often accepted by the unconscious because they appear logical. However, if we analyze such statements we are likely to find fallacies and/or limiting beliefs that can be overcome.

Complex Equivalence

A complex equivalence is a statement that suggests how two things are the same, or equivalent to each other; or otherwise suggests that one action has a meaning other than its true meaning.

Often, words that connect two statements to make them appear equivalent are omitted as they are presumed “understood by the listener”. Such words may include “that means”, “that just means”, “obviously”, “I can tell”, etc.

Examples of complex equivalence include:

“You’re not looking at me when I speak, so you’re not listening to what I say.) (Do I need to look at you to hear what you’re saying?)

“The boss has his door closed – He’s planning to fire me.” (Does he fire someone every time he closes the door?)

“You’re not listening to me – You obviously don’t care.” (How does lack of focus equate to lack of caring?)

# NOTE: Complex equivalences are often used to create a relationship between two statements that are effectively unrelated. To challenge these, it is important to recognize the relationship between those sentences and directly question them (As in examples 1 and 3 above) or provide a counter-example (using an opposite or contrary situation – As in example 2 above).

Generalizations

Generalization occurs when we speak in terms of groups, categories, or classifications. As humans, we all have the need to label the things in our environments as our brains create maps of our worlds. This is, to one degree or another, different for every individual.

Generalizations may also occur when we take an event or experience that has occurred in one situation, and apply that event or experience to other situations that appear similar. An example of this would be to say “Children need discipline.” This statement does not apply universally… Not all children need discipline, and those that may, would not need discipline all of the time. The need for discipline itself may also be a subjective viewpoint (one’s own perspective).

All Things In The Universe Are Dependent On Circumstance

- Dan Blaze

Modal Operators

Modal operators (often called “modal verbs” or simply “modals”) are auxiliary verbs, meaning that they add either functional or grammatical meaning to another verb, which simply means they change the meaning or outcome represented by that other verb. Modals precede the verb which they alter, and modify ‘how, when, or if’ the second verb is performed.

Let’s just take a look at a close example to ensure comprehension: Assume I said “I will go to Disney Land”. The word “will” is a |modal operator that modifies the meaning of the word “go”. This is a completely different sentence then simply stating “I go to Disney Land” (which is an unspecific sentence fragment). Similarly we can replace the word “go” with the word “want” which can also act as a modal operator “I want to go to Disney Land”… In this example, the word “go” does not have the meaning of doing or having done.

The following is a short list of modal operators:

1) Modal Operators of Necessity

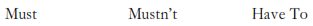

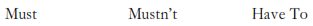

These are words that denote the necessity of doing something (or not doing something), and are used when there is a belief that something must or must not be done. Perhaps we believe that it must be done a certain way; or at a certain time; or possibly with certain people or at a certain place. This type of language is heard often in statements such as “You have to get a good education to get a good job with a good company” or “You must eat your veggies if you want to be strong”. It is possible, however, that such statements of necessity could be made under presumptuous beliefs, thus limiting options that are available to us. These words include:

When these words are used, directly question both the reason as well as the authority behind the statement. If no reasoning or authority exists, then question the future outcome by starting questions with “What would happen if…” or “What would prevent you from…”. For example:

Statement: You really have to get your act together.

Question Reason: Why must I get my act together?

Question Authority: According to Whom?

Question Future Outcome: What would happen if I didn’t?

2) Modal Operators of Possibility

Beliefs can be liberated or limited by the boundaries that we set upon ourselves. Often, these boundaries derive from our previous experiences, and/or our understanding of the world around us. The problem is that we often develop or create beliefs that are incorrect, either due to lack of effort in our previous experiences or by applying a context-specific result to other contexts.

To explain this a bit further, consider the following:

a) A student who as previously been good in mathematics takes a university course in business accounting and finds it too difficult. (Previous context-specific results – being good at math – were erroneously applied to business accounting in the belief that they are essentially the same).

b) The same student then states “I can’t do accounting” (Previous experience in attempting to do accounting creates a limiting belief about future abilities).

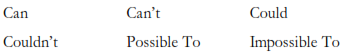

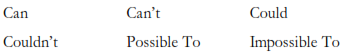

Modal operators of possibility include:

Much like those of necessity, modal operators of possibility can be approached by either directly seeking reason, questioning authority or attending to future outcomes.

Statement: I can’t learn all of this!

Question Reason: Why can’t you learn all of this?

Question Authority: Who says you can’t learn all of this?

Question Future Outcome: What would prevent you from learning all of this?

3) Modal Operators of Judgment

Judgments are in essence decisions, and much like making decisions, people make judgments through a series of mental filters. A person’s judgment of something can first go through an assessment of previous experiences, biases, social and moral interpretation, contextual evaluation, and so on. Modal operators of judgment can act much like those of necessity, in that they lead to unwarranted freedoms, or to unnecessary limitations, both of which should be questioned accordingly.

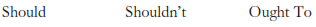

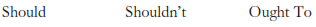

Below is a short list of modal operators of judgment:

Again, modal operators or judgment can be questioned in the same manner as those of necessity or possibility: By questioning reason, authority or future outcome