III

DOMESTIC SLAVERY ON THE MAINLAND

Some two hundred miles south of St. Paul de Loanda, you come to a deep and quiet inlet, called Lobito Bay. Hitherto it has been desert and unknown—a spit of waterless sand shutting in a basin of the sea at the foot of barren and waterless hills. But in twenty years’ time Lobito Bay may have become famous as the central port of the whole west coast of Africa, and the starting-place for traffic with the interior. For it is the base of the railway scheme known as the “Robert Williams Concession,” which is intended to reach the ancient copper-mines of the Katanga district in the extreme south of the Congo State, and so to unite with the “Tanganyika Concession.” It would thus connect the west coast traffic with the great lakes and the east. A branch line might also turn off at some point along the high and flat watershed between the Congo and Zambesi basins, and join the Cape Town railway near Victoria Falls. Possibly before the Johannesburg gold is exhausted, passengers from London to the Transvaal will address their luggage “viâ Lobito Bay.”

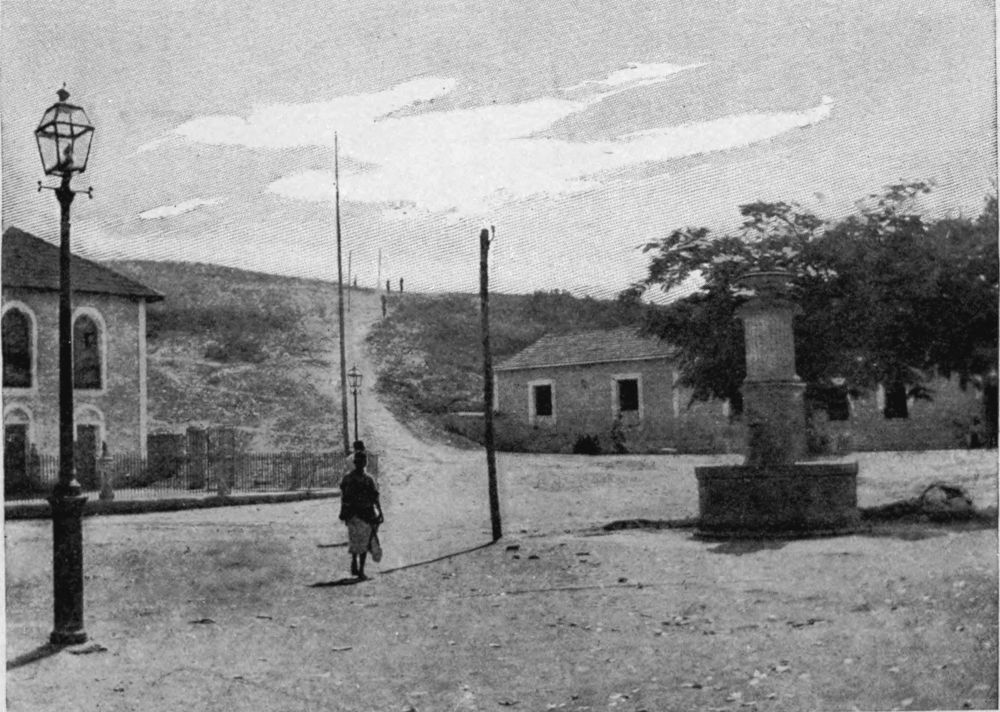

FIRST MAIL-STEAMER AT LOBITO BAY

But this is only prophecy. What is certain is that on January 5, 1905, a mail-steamer was for the first time warped alongside a little landing-stage of lighters, in thirty-five feet of water, and I may go down to fame as the first man to land at the future port. What I found were a few laborers’ huts, a tent, a pile of sleepers, a tiny engine puffing over a mile or two of sand, and a large Portuguese custom-house with an eye to possibilities. I also found an indomitable English engineer, engaged in doing all the work with his own hands, to the entire satisfaction of the native laborers, who encouraged him with smiles.

At present the railway, which is to transform the conditions of Central Africa, runs as a little tram-line for about eight miles along the sand to Katumbella. There it has something to show in the shape of a great iron bridge, which crosses the river with a single span. The day I was there the engineers were terrifying the crocodiles by knocking away the wooden piles used in the construction, and both natives and Portuguese were awaiting the collapse of the bridge with the pleasurable excitement of people who await a catastrophe that does not concern themselves. But; to the general disappointment, the last prop was knocked away and the bridge still stood. It was amazing. It was contrary to the traditions of Africa and of Portugal.

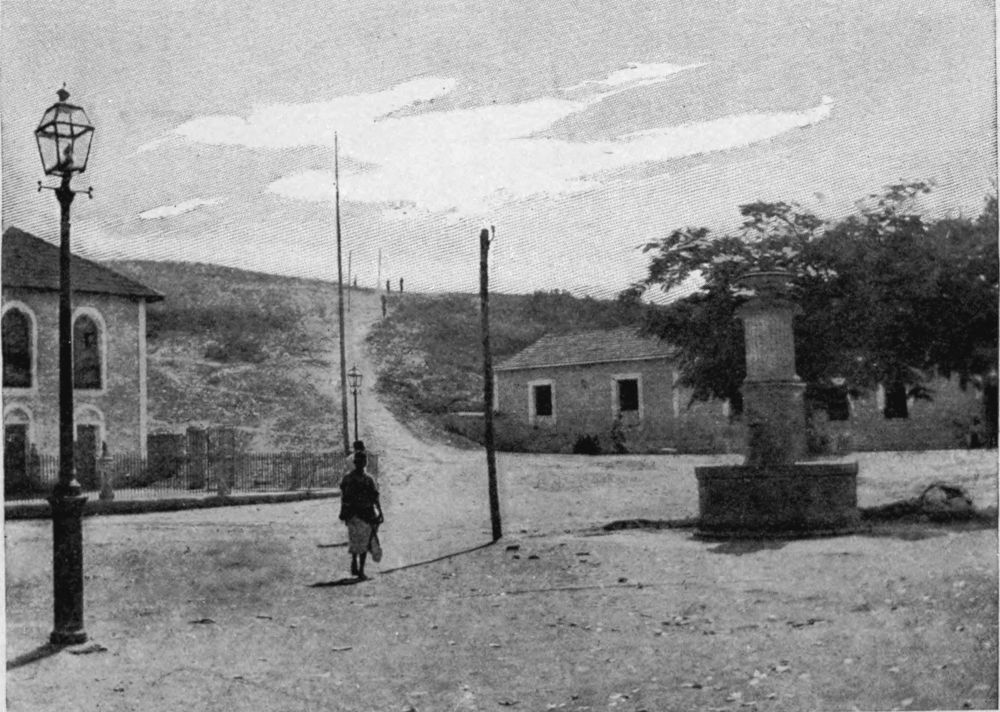

Katumbella itself is an old town, with two old forts, a dozen trading-houses, and a river of singular beauty, winding down between mountains. It is important because it stands on the coast at the end of the carriers’ foot-path, which has been for centuries the principal trade route between the west and the interior. One sees that path running in white lines far over the hills behind the town, and up and down it black figures are continually passing with loads upon their heads. They bring rubber, beeswax, and a few other products of lands far away. They take back enamelled ware, rum, salt, and the bales of cotton cloth from Portugal and Manchester which, together with rum, form the real coinage and standard of value in Central Africa, salt being used as the small change. The path ends, vulgarly enough, at an oil-lamp in the chief street of Katumbella. Yet it is touched by the tragedy of human suffering. For this is the end of that great slave route which Livingstone had to cross on his first great journey, but otherwise so carefully avoided. This is the path down which the caravans of slaves from the basin of the Upper Congo have been brought for generations, and down this path within the last three or four years the slaves were openly driven to the coast, shackled, tied together, and beaten along with whips, the trader considering himself fairly fortunate if out of his drove of human beings he brought half alive to the market. There is a notorious case in which a Portuguese trader, who still follows his calling unchecked, lost six hundred out of nine hundred on the way down. At Katumbella the slaves were rested, sorted out, dressed, and then taken on over the fifteen miles to Benguela, usually disguised as ordinary carriers. The traffic still goes on, almost unchecked. But of that ancient route from Bihé to the coast I shall write later on, for by this path I hope to come when I emerge from the interior and catch sight of the sea again between the hills.

END OF THE GREAT SLAVE ROUTE AT KATUMBELLA

As to the town of Benguela, there is something South African about it. Perhaps it comes from the eucalyptus-trees, the broad and sandy roads ending in scrubby waste, and the presence of Boer transport-riders with their ox-wagons from southern Angola. But the place is, in fact, peculiarly Portuguese. Next to Loanda, it is the most important town in the colony, and for years it was celebrated as the very centre of the slave-trade with Brazil. In the old days when Great Britain was the enthusiastic opponent of slavery in every form, some of her men-of-war were generally hanging about off Benguela on the watch. They succeeded in making the trade difficult and unlucrative; but we have all become tamer now and more ready to show consideration for human failings, provided they pay. Call slaves by another name, legalize their position by a few printed papers, and the traffic becomes a commercial enterprise deserving of every encouragement. A few years ago, while gangs were still being whipped down to the coast in chains, one of the most famous of living African explorers informed the captain of a British gun-boat what was the true state of things upon a Portuguese steamer bound for San Thomé. The captain, full of old-fashioned indignation, proposed to seize the ship. Whereupon the British authorities, flustered at the notion of such impoliteness, reminded him that we were now living in a civilized age. These men and women, who had been driven like cattle over some eight hundred miles of road to Benguela were not to be called slaves. They were “serviçaes,” and had signed a contract for so many years, saying they went to San Thomé of their own free will. It was the free will of sheep going to the butcher’s. Every one knew that. But the decencies of law and order must be observed.

Within the last two or three years the decencies of law and order have been observed in Benguela with increasing care. There are many reasons for the change. Possibly the polite representations of the British Foreign Office may have had some effect; for England, besides being Portugal’s “old ally,” is one of the best customers for San Thomé cocoa, and it might upset commercial relations if the cocoa-drinkers of England realized that they were enjoying their luxury, or exercising their virtue, at the price of slave labor. Something may also be due to the presence of the English engineers and mining prospectors connected with the Robert Williams Concession. But I attribute the change chiefly to the helpless little rising of the natives, known as the “Bailundu war” of 1902. Bailundu is a district on the route between Benguela and Bihé, and the rising, though attributed to many absurd causes by the Portuguese—especially to the political intrigues of the half-dozen American missionaries in the district—was undoubtedly due to the injustice, violence, and lust of certain traders and administrators. The rising itself was an absolute failure. Terrified as the Portuguese were, the natives, were more terrified still. I have seen a place where over four hundred native men, women, and children were massacred in the rocks and holes where their bones still lie, while the Portuguese lost only three men. But the disturbance may have served to draw the attention of Portugal to the native grievances. At any rate, it was about the same time that two of the officers at an important fort were condemned to long terms of imprisonment and exile for open slave-dealing, and Captain Amorim, a Portuguese gunner, was sent out as a kind of special commissioner to make inquiries. He showed real zeal in putting down the slave-trade, and set a large number of slaves at liberty with special “letters of freedom,” signed by himself—most of which have since been torn up by the owners. His stay was, unhappily, short, but he returned home, honored by the hatred of the Portuguese traders and officials in the country, who did their best to poison him, as their custom is. His action and reports were, I think, the chief cause of Portugal’s “uneasiness.”

So the horror of the thing has been driven under the surface; and what is worse, it has been legalized. Whether it is diminished by secrecy and the forms of law, I shall be able to judge better in a few months’ time. I found no open slave-market existing in Benguela, such as reports in Europe would lead one to expect. The spacious court-yards or compounds round the trading-houses are no longer crowded with gangs of slaves in shackles, and though they are still used for housing the slaves before their final export, the whole thing is done quietly, and without open brutality, which is, after all, unprofitable as well as inhuman.

In the main street there is a government office where the official representative of the “Central Committee of Labor and Emigration for the Islands” (having its headquarters in Lisbon) sits in state, and under due forms of law receives the natives, who enter one door as slaves and go out of another as “serviçaes.” Everything is correct. The native, who has usually been torn from his home far in the interior, perhaps as much as eight hundred miles away, and already sold twice, is asked by an interpreter if it is his wish to go to San Thomé, or to undertake some other form of service to a new master. Of course he answers, “Yes.” It is quite unnecessary to suppose, as most people suppose, that the interpreter always asks such questions as, “Do you like fish?” or, “Will you have a drink?” though one of the best scholars in the languages of the interior has himself heard those questions asked at an official inspection of “serviçaes” on board ship. It would be unnecessary for the interpreter to invent such questions. If he asked, “Is it your wish to go to hell?” the “serviçal” would say “yes” just the same. In fact, throughout this part of Africa, the name of San Thomé is becoming identical with hell, and when a man has been brought hundreds of miles from his home by an unknown road, and through long tracts of “hungry country”—when also he knows that if he did get back he would probably be sold again or killed—what else can he answer but “yes”? Under similar circumstances the Archbishop of Canterbury would answer the same.

The “serviçal” says “yes,” and so sanctions the contract for his labor. The decencies of law and order are respected. The government of the colony receives its export duty—one of the queerest methods of “protecting home industries” ever invented. All is regular and legalized. A series of new rules for the serviçal’s comfort and happiness during his stay in the islands was issued in 1903, though its stipulations have not been carried out. And off goes the man to his death in San Thomé or Il Principe as surely as if he had signed his own death-warrant. To be sure, there are regulations for his return. By law, three-fifths of his so-called monthly wages are to be set aside for a “Repatriation Fund,” and in consideration of this he is granted a “free passage” back to the coast. A more ingenious trick for reducing the price of labor has never been invented, but, for very shame, the Repatriation Fund has ceased to exist, if it ever existed. Ask any honest man who knows the country well. Ask any Scottish engineer upon the Portuguese steamers that convey the “serviçaes” to the islands, and he will tell you they never return. The islands are their grave.

These are things that every one knows, but I will not dwell upon them yet or even count them as proved, for I have still far to go and much to see. Leaving the export trade in “contracted labor,” I will now speak of what I have actually seen and known of slavery on the mainland under the white people themselves. I have heard the slaves in Angola estimated at five-sixths of the population by an Englishman who has held various influential positions in the country for nearly twenty years. The estimate is only guesswork, for the Portuguese are not strong in statistics, especially in statistics of slavery. But including the very large number of natives who, by purchase or birth, are the family slaves of the village chiefs and other fairly prosperous natives, we might probably reckon at least half the population as living under some form of slavery—either in family slavery to natives, or general slavery to white men, or in plantation slavery (under which head I include the export trade). I have referred to the family slavery among the natives. Till lately it has been universal in Africa, and it still exists in nearly all parts. But though it is constantly pleaded as their excuse by white slave-owners, it is not so shameful a thing as the slavery organized by the whites, if only because whites do at least boast themselves to be a higher race than natives, with higher standards of life and manners. From what I have seen of African life, both in the south and west, I am not sure that the boast is justified, but at all events it is made, and for that reason white men are precluded from sheltering themselves behind the excuse of native customs.

On the same steamer by which I reached Benguela there were five little native boys, conspicuous in striped jerseys, and running about the ship like rats. I suppose they were about ten to twelve years old, perhaps less. I do not know where they came from, but it must have been from some fairly distant part of the interior, for, like all natives who see stairs for the first time, they went up and down them on their hands and knees. They were travelling with a Portuguese, and within a week of landing at Benguela he had sold them all to other white owners. Their price was fifty milreis apiece (nearly £10). Their owner did rather well, for the boys were small and thin—hardly bigger than another native slave boy who was at the same time given away by one Portuguese friend to another as a New-Year’s present. But all through this part of the country I have found the price of human beings ranging rather higher than I expected, and the man who told me the price of the boys had himself been offered one of them at that figure, and was simply passing on the offer to myself.

Perhaps I was led to underestimate prices a little by the statement of a friend in England that at Benguela one could buy a woman for £8 and a girl for £12. He had not been to that part of the coast himself, though for five years he had lived in the Katanga district of the Congo State, from which large numbers of the slaves are drawn. Perhaps he had forgotten to take into account the heavy cost of transport from the interior and the risk of loss by death upon the road. Or perhaps he reckoned by the exceptionally low prices prevailing after the dry season of 1903, when, owing to a prolonged drought, the famine was severe in a district near the Kunene in southeast Angola, and some Portuguese and Boer traders took advantage of the people’s hunger to purchase oxen and children cheap in exchange for mealies. Similarly, in 1904, women were being sold unusually cheap in a district by the Cuanza, owing to a local famine. Livingstone, in his First Expedition to Africa, said he had never known cases of parents selling children into slavery, but Mr. F. S. Arnot, in his edition of the book, has shown that such things occur (though as a rule a child is sold by his maternal uncle), and I have myself heard of several instances in the last few weeks, both for debt and hunger. Necessity is the slave-trader’s opportunity, and under such conditions the market quotations for human beings fall, in accordance with the universal economics.

The value of a slave, man or woman, when landed at San Thomé, is about £30, but, as nearly as I could estimate, the average price of a grown man in Benguela is £20 (one hundred dollars). At that price the traders there would be willing to supply a large number. An Englishman whom I met there had been offered a gang of slaves, consisting of forty men and women, at the rate of £18 a head. But the slaves were up in Bihé, and the cost of transport down to the coast goes for something; and perhaps there was “a reduction on taking a quantity.” However, when he was in Bihé, he had bought two of them from the Portuguese trader at that rate. They were both men. He had also bought two boys farther in the interior, but I do not know at what price. One of them had been with the Batatele cannibals, who form the chief part of the “Révoltés,” or rebels, against the atrocious government of the Belgians on the Upper Congo. Perhaps the boy himself really belonged to the race which had sold him to the Bihéan traders. At all events, the racial mark was cut in his ears, and the other “boys” in the Englishman’s service were never tired of chaffing him upon his past habits. Every night they would ask him how many men he had eaten that day. But a point was added to the laugh because the ex-cannibal was now acting as cook to the party. Under their new service all these slaves received their freedom.

The price of women on the mainland is more variable, for, as in civilized countries, it depends almost entirely on their beauty and reputation. Even on the Benguela coast I think plenty of women could be procured for agricultural, domestic, and other work at £15 a head or even less. But for the purposes for which women are often bought the price naturally rises, and it depends upon the ordinary causes which regulate such traffic. A full-grown and fairly nice-looking woman may be bought from a trader for £18, but for a mature girl a man must pay more. At least a stranger who is not connected with the trade has to pay more. While I was in the town a girl was sold to a prospector, who wanted her as his concubine during a journey into the interior. Her owner was an elderly Portuguese official of some standing. I do not know how he had obtained her, but she was not born in his household of slaves, for he had only recently come to the country. Most likely he had bought her as a speculation, or to serve as his concubine if he felt inclined to take her. The price finally arranged between him and the prospector for the possession of the girl was one hundred and twenty-five milreis, which was then nearly equal to £25. For the visit of the King of Portugal to England and the revival of the “old alliance” had just raised the value of the Portuguese coinage.

When the bargain was concluded, the girl was led to her new master’s room and became his possession. During his journey into the interior she rode upon his wagon. I saw them often on the way, and was told the story of the purchase by the prospector himself. He did not complain of the price, though men who were better acquainted with the uses of the woman-market considered it unnecessarily high. But it is really impossible to fix an average standard of value where such things as beauty and desire are concerned. The purchaser was satisfied, the seller was satisfied. So who was to complain? The girl was not consulted, nor did the question of her price concern her in the least.

I was glad to find that the Portuguese official who had parted with her on these satisfactory terms was no merely selfish speculator in the human market, as so many traders are, but had considered the question philosophically, and had come to the conclusion that slavery was much to a slave’s advantage. The slave, he said, had opportunities of coming into contact with a higher civilization than his own. He was much better off than in his native village. His food was regular, his work was not excessive, and, if he chose, he might become a Christian. Being an article of value, it was likely that he would be well treated. “Indeed,” he continued, in an outburst of philanthropic emotion, “both in our own service and at San Thomé, the slave enjoys a comfort and well-being which would have been forever beyond his reach if he had not become a slave!” In many cases, he asserted, the slave owed his very life to slavery, for some of the slaves brought from the interior were prisoners of war, and would have been executed but for the profitable market ready to receive them. As he spoke, the old gentleman’s face glowed with noble enthusiasm, and I could not but envy him his connection with an institution that was at the same time so salutary to mankind and so lucrative to himself.

As to the slave’s happiness on the islands, I cannot yet describe it, but according to the reports of residents, ships’ officers, and the natives themselves, it is brief, however great. What sort of happiness is enjoyed on the Portuguese plantations of Angola itself I have already described. As to the comfort and joy of ordinary slavery under white men, with all its advantages of civilization and religion, the beneficence of the institution is somewhat dimmed by a few such things as I have seen, or have heard from men whom I could trust as fully as my own eyes. At five o’clock one afternoon I saw two slaves carrying fish through an open square at Benguela, and enjoying their contact with civilization in the form of another native, who was driving them along like oxen with a sjambok. The same man who was offered the forty slaves at £18 a head had in sheer pity bought a little girl from a Portuguese lady last autumn, and he found her back scored all over with the cut of the chicote, just like the back of a trek-ox under training. An Englishman coming down from the interior last African winter, was roused at night by loud cries in a Portuguese trading-house at Mashiko. In the morning he found that a slave had been flogged, and tied to a tree in the cold all night. He was a man who had only lately lost his liberty, and was undergoing the process which the Portuguese call “taming,” as applied to new slaves who are sullen and show no pleasure in the advantages of their position. In another case, only a few weeks ago, an American saw a woman with a full load on her head and a baby on her back passing the house where he happened to be staying. A big native, the slave of a Portuguese trader in the neighborhood, was dragging her along with a rope, and beating her with a whip as she went. The American brought the woman into the house and kept her there. Next day the Portuguese owners came in fury with forty of his slaves, breathing out slaughters, but, as is usual with the Portuguese, he shrank up when he was faced with courage. The American refused to give the woman back, and ultimately she was restored to her own distant village, where she still is.

I would willingly give the names in the last case and in all others; but one of the chief difficulties of the whole subject is that it is impossible to give names without exposing people out here to the hostility and persecution of the Portuguese authorities and traders. In most instances, also, not only the people themselves, but all the natives associated with them, would suffer, and the various kinds of work in which they are engaged would come to an end. It is the same fear which keeps the missionaries silent. The Catholic missions are supported by the state. The other missions exist on sufferance. How can missionaries of either division risk the things they have most at heart by speaking out upon a dangerous question? They are silent, though their conscience is uneasy, unless custom puts it to sleep.

Custom puts us all to sleep. Every one in Angola is so accustomed to slavery as part of the country’s arrangements that hardly anybody considers it strange. It is regarded either as a wholesome necessity or as a necessary evil. When any question arises upon the subject, all the antiquated arguments in favor of slavery are trotted out again. We are told that but for slavery the country would remain savage and undeveloped; that some form of compulsion is needed for the native’s good; that in reality he enjoys more freedom and comfort as a slave than in his free village. Let us at once sweep away all the talk about the native’s good. It is on a level with the cant which said the British fought the Boers and brought the Chinese to the Transvaal in order to extend to both races a higher form of religion. The only motive for slavery is money-making, and the only argument in its favor is that it pays. That is the root of the matter, and as long as we stick to that we shall, at least, be saved from humbug.

As to the excuse that there is a difference between slavery and “contracted labor,” this is no more than legal cant, just as the other pleas are philanthropic or religious cant. Except in the eyes of the law, it makes no difference whether a man is a “serviçal” or a slave; it makes no difference whether a written contract exists or not. I do not know whether the girl I mentioned had signed a contract expressing her willingness to serve as the prospector’s concubine for five years, after which she was to be free unless the contract were renewed. But I do know that whether she signed the contract or not, her price and position would have been exactly the same, and that before the five years are up she will in all probability have been sold two or three times over, at diminishing prices. The “serviçal” system is only a dodge to delude the antislavery people, who were at one time strong in Great Britain, and have lately shown signs of life in Portugal. Except in the eyes of a law which is hardly ever enforced, slavery exists almost unchecked. Slaves work the plantations, slaves serve the traders, slaves do the housework of families. Ordinary free wage-earners exist in the towns and among the carriers, but, as a rule, throughout the country the system of labor is founded on slavery, and very few of the Portuguese or foreign residents in Angola would hesitate to admit it.

From Benguela I determined to strike into a district which has long had an evil reputation as the base of the slave-trade with the interior—a little known and almost uninhabited country.