IV

ON ROUTE TO THE SLAVE CENTRE

He who goes to Africa leaves time behind. Next week is the same as to-morrow, and it is indifferent whether a journey takes a fortnight or two months. That is why the ox-wagon suits the land so well. Mount an ox-wagon and you forget all time. Like the to-morrows of life, it creeps in its petty pace, and soon after its wheels have reached their extreme velocity of three miles an hour you learn how vain are all calculations of pace and years. Yet, except in the matter of speed, which does not count in Africa, the ox-wagon has most of the qualities of an express-train, besides others of greater value. Its course is at least equally adventurous, and it affords a variety of sensations and experiences quite unknown to the ordinary railway passenger.

Let me take an instance from the recent journey on which I have crossed some four hundred and fifty or five hundred miles of country in two months. A good train would have traversed the distance in a winter’s night, and have left only a tedious blank upon the mind. On a railway what should I have known of a certain steep descent which we approached one silent evening after rain? The red surface was just slippery with the wet. The oxen were going quietly along, when, all of a sudden, they were startled by the heavy thud of the wheels jolting over a tree stump on the track. Within a few yards of the brink they set off at a trot, the long and heavy chain hanging loose between them.

“Kouta! Kouta ninni!” (“Brake! Hard on!”) shouted the driver, and we felt the Ovampo boy behind the wagon whirl the screw round till the hind wheels were locked. But it was too late. We were over the edge already. Backing and slipping and pulling every way, striking with their horns, charging one another helplessly from behind, the oxen swept down the steep. Behind them, like a big gun got loose, came the wagon, swaying from side to side, leaping over the rocks, plunging into the holes, at every moment threatening to crush the hinder oxen of the span. Then it began to slide sideways. It was almost at right angles to the track. In another second it would turn clean over, with all four wheels in air, or would dash us into a great tree that stood only a few yards down.

“Kouta loula!” (“Loose the brake!”) yelled the driver, but nothing could stop the sliding now. We clung on and thought of nothing. Men on the edge of death think of nothing. Suddenly the near hind wheel was thrown against a high ridge of clay. The wagon swung straight, and we were plunged into a river among the struggling oxen, all huddled together and entangled in the chain.

AWKWARD CROSSING

“That was rather rapid,” I said, as the wagon came to a dead stop in the mud and we took to the water, but in no language could I translate the expression of the driver’s emotions.

Only last wet season the owner of a wagon started down a place like that with twenty-four fine oxen, and at the bottom he had eight oxen, and more beef than he could salt.

Beside another hill lies the fresh grave of a poor young Boer, who was thrown under his wagon wheels and never out-spanned again. Such are the interests of an ox-wagon when it takes to speed.

Or what traveller by train could have enjoyed such experiences as were mine in crossing the Kukema—a river that forms a boundary of Bihé? At that point it was hardly more than five feet deep and twenty yards wide. In a train one would have leaped over it without pause or notice. But in a wagon the passage gave us a whole long day crammed with varied labor and learning. Leading the oxen down to the brink at dawn, we out-spanned and emptied the wagon of all the loads. Then we lifted its “bed” bodily off the four wheels, and spreading the “sail,” or canvas hood, under it, we launched it with immense effort into the water as a raft. We anchored it firmly to both banks by the oxen’s “reems” (I do not know how the Boers spell those strips of hide, the one thing, except patience, necessary in African travel), and dragging it to and fro through the water, we got the loads over dry in about four journeys. Then the oxen were swum across, and tying some of them to the long chain on the farther side, we drew the wheels and the rest of the wagon under water into the shallows. Next came the task of taking off the “sail” in the water and floating the “bed” into its place upon the beam again—a lifelong lesson in applied hydraulics. When at last the sun set and white man and black emerged naked, muddy, and exhausted from the water, while the wagon itself wallowed triumphantly up the bank, I think all felt they had not lived in vain. Though, to be sure, it was wet sleeping that night, and the rain came sousing down as if poured out of one immeasurable slop-pail.

A railway bridge? What a dull and uninstructive substitute that would have been!

Or consider the ox, how full of personality he is compared to the locomotive! Outwardly he is far from emotional. You cannot coax him as you coax a horse or a dog. A fairly tame ox will allow you to clap his hind quarters, but the only real pleasure you can give him is a lick of salt. For salt even a wild ox will almost submit to be petted. The smell of the salt-bag is enough to keep the whole span sniffing and lowing round the wagon instead of going to feed, and, especially on the “sour veldt,” the Sunday treat of salt spread along a rock is a festival of luxury.

But unexpressive as oxen are, one soon learns the inner character of each. There is the wise and willing ox, who will stick to the track and always push his best. He is put at the head of the span. In the middle comes the wild ox, who wants to go any way but the right; the sullen ox, who needs the lash; and the well-behaved representative of gentility, who will do anything and suffer anything rather than work. Nearest the wagon, if possible for as many as four spans, you must put the strong and well-trained oxen, who answer quickly to their names. On them depends the steering and safety of the wagon. At the sound of his name each ox is trained to push his side of the yoke forward, and round trees or corners the wagon follows the curve of safety.

“Blaawberg! Shellback! Rachop! Blomveldt!” you cry. The oxen on the left of the four last spans push forward the ends of their yokes, and edging off to the right, the wagon moves round the segment of an arc. To drive a wagon is like coxing an eight without a rudder.

But on a long and hungry trek even the leaders will sometimes turn aside into the bush for tempting grass, or as a hint that it is time to stop. In a moment there is the wildest confusion. The oxen behind are dragged among the trees. The chain gets entangled; two oxen pull on different sides of a standing trunk; yoke-pegs crack; necks are throttled by the halters; the wagon is dashed against a solid stump, and trees and stump and all have to be hewn down with the axe before the span is free again. Sometimes the excited and confused animals drag at the chain while one ox is being helplessly crushed against a tree. Often a horn is broken off. I know nothing that suggests greater pain than the crack of a horn as it is torn from the skull. The ox falls silently on his knees. Blood streams down his face. The other oxen go on dragging at the chain. When released from the yoke, he rushes helplessly over the bush, trying to hide himself. But flinging him on his side and tying his legs together, the natives bind up the horn, if it has not actually dropped, with a plaster of a poisonous herb they call “moolecky,” to keep the blow-flies away. Sometimes it grows on again. Sometimes it remains loose and flops about. But, as a rule, it has to be cut off in the end.

To avoid such things most transport-riders set a boy to walk in front of the oxen as “toe-leader,” though it is a confession of weakness. Another difficulty in driving the ox is his peculiar horror of mud from the moment that he is in-spanned. By nature he loves mud next best to food and drink. He will wallow in mud all a tropical day, and the more slimy it is, the better he likes it. But put him in the yoke, and he becomes as cautious of mud as a cat, as dainty of his feet as a lady crossing Regent Street. It seems strange at first, but he has his reasons. When he comes to one of those ghastly mud-pits (“slaughter-holes” the Boers call them), which abound along the road in the wet season, his first instinct is to plunge into it; but reflection tells him that he has not time to explore its cool depths and delightful stickiness, and that if he falls or sticks the team behind and perhaps the wagon itself will be upon him. So he struggles all he can to skirt delicately round it, and if he is one of the steering oxen, the effort brings disaster either on the wagon or himself. No less terrible is his fate when for hour after hour the wagon has to plough its way through one of the upland bogs; when the wheels are sunk to the hubs, and the legs of all the oxen disappear, and the shrieking whips and yelling drivers are never for a moment still. Why the ox also very strongly objects to getting his tail wet I have not found out.

Another peculiarity is that the ox is too delicate to work if it is raining. Cut his hide to ribbons with rhinoceros whips, rot off his tail with inoculation for lung-sickness, let ticks suck at him till they swell as large as cherries with his blood—he bears all patiently. But if a soft shower descends on him while he is in the yoke, he will work no more. Within a minute or two he gets the sore hump—a terrible thing to have. There is nothing to do but to stop. The hump must be soothed down with wagon-grease—a mixture of soft-soap, black-lead, and tar—and I have heard of wagons halted for weeks together because the owner drove his oxen through a storm. Seeing that it rains in water-spouts nearly every morning or afternoon from October to May, the working-hours are considerably shortened, and unhappy is the man who is in haste. I was in haste.

To be happy in Africa a man should have something oxlike in his nature. Like an ox, or like “him that believeth,” he must never make haste. He must accept his destiny and plod upon his way. He must forget emotion and think no more of pleasures. He must let time run over him, and hope for nothing greater than a lick of salt.

But there is one kind of ox which develops further characteristics, and that is the riding-ox. He is the horse of Angola and of all Central Africa where he can live. With ring in nose and saddle on back, he will carry you at a swinging walk over the country, even through marshes where a horse or a donkey would sink and shudder and groan. One of my wagon team was a riding-ox, and it took four men to catch and saddle him. To avoid the dulness of duty he would gallop like a racer and leap like a deer. But when once saddled his ordinary gait was discreet and solemn; and though his name was Buller, I called him “Old Ford,” because he somehow reminded me of the Chelsea ’bus.

All the oxen in the team, except Buller, were called by Boer names. Nor was this simply because Dutch is the natural language of oxen. Very nearly every one concerned with wagons in Angola is a Boer, and it is to Boers that the Portuguese owe the only two wagon tracks that count in the country—the road from Benguela through Caconda to Bihé and on towards the interior, and the road up from Mossamedes, which joins the other at Caconda. I think these tracks form the northernmost limit of the trek-ox in Africa, and his presence is entirely due to a party of Boers who left the Transvaal rather more than twenty years ago, driven partly by some religious or political difference, but chiefly by the wandering spirit of Boers. I have conversed with a man who well remembers that long trek—how they Started near Mafeking and crept through Bechuanaland, and skirting the Kalahari Desert, crossed Damaraland, and reached the promised land of Angola at last. They were five years on the way—those indomitable wanderers. Once they stopped to sow and reap their corn. For the rest they lived on the game they shot. Now you find about two hundred families of them scattered up and down through South Angola, chiefly in the Humpata district. They are organized for defence on the old Transvaal lines, and to them the Portuguese must chiefly look to check an irruption of natives, such as the Cunyami are threatening now on the Cunene River.

Yet the Portuguese have taken this very opportunity (February, 1905) for worrying them all about licenses for their rifles, and threatening to disarm them if all the taxes are not paid up in full. At various points I met the leading Boers going up to the fort at Caconda, brooding over their grievances, or squatted on the road, discussing them in their slow, untiring way. On further provocation they swore they would trek away into Barotzeland and put themselves under British protection. They even raised the question whether the late war had not given them the rights of British subjects already. A slouching, unwashed, foggy-minded people they are, a strange mixture of simplicity and cunning, but for knowledge of oxen and wagons and game they have no rivals, and in war I should estimate the value of one Boer family at about ten Portuguese forts. They trade to some extent in slaves, but chiefly they buy them for their own use, and they almost always give them freedom at the time of marriage. Their boy slaves they train with the same rigor as their oxen, but when the training is complete the boy is counted specially valuable on the road.

Distances in Africa are not reckoned by miles, but by treks or by days. And even this method is very variable, for a journey that will take a fortnight in the dry season may very well take three months in the wet. A trek will last about three hours, and the usual thing is two treks a day. I think no one could count on more than twelve miles a day with a loaded wagon, and I doubt if the average is as much as ten. But it is impossible to calculate. The record from Bihé to Benguela by the road is six weeks, but you must not complain if a wagon takes six months, and the journey used to be reckoned at a year, allowing time for shooting food on the way. In a straight line the distance is about two hundred and fifty miles, or, by the wagon road, something over four hundred and fifty, as nearly as I can estimate. But when it takes you two or three days to cross a brook and a fortnight to cross a marsh, distance becomes deceptive.

One thing is very noticeable along that wagon road: from end to end of it hardly a single native is to be seen. After leaving Benguela, till you reach the district of Bihé, you will see only one native village, and that is three miles from the road. Much of the country is fertile. Villages have been plentiful in the past. The road passes through their old fields and gardens. Sometimes the huts are still standing, but all is silent and deserted now. Till this winter there was one village left, close upon the road, about a day’s trek past Caconda. But when I hoped to buy a few potatoes or peppers there, I found it abandoned like the rest. Where the road runs, the natives will not stay. Exposed continually to the greed, the violence, and lust of white men and their slaves, they cannot live in peace. Their corn is eaten up, their men are beaten, their women are ravished. If a Portuguese fort is planted in the neighborhood, so much the worse. Time after time I have heard native chiefs and others say that a fort was the cruelest thing to endure of all. It is not only the exactions of the Chefe in command himself, though a Chefe who comes for about eighteen months at most, who depends entirely on interpreters, and is anxious to go home much richer than he came, is not likely to be particular. But it is the brutality of the handful of soldiers under his command. The greater part of them are natives from distant tribes, and they exercise themselves by plundering and maltreating any villagers within reach, while the Chefe remains ignorant or indifferent. So it comes that where a road or fort or any other sign of the white man’s presence appears the natives quit their villages one by one, and steal away to build new homes beyond the reach of the common enemy. This is, I suppose, that “White Man’s Burden” of which we have heard so much. This is “The White Man’s Burden,” and it is the black man who takes it up.

To the picturesque traveller who is provided with plenty of tinned things to eat, the solitude of the road may add a charm. For it is far more romantic to hear the voice of lions than the voice of man. But, indeed, to every one the road is of interest from its great variety. Here in a short space are to be seen the leading characteristics of all the southern half of Africa—the hot and dry edging near the shore, the mountain zone, and the great interior plateau of forest or veldt, out of which, I suppose, the mountain zone has been gradually carved, and is still being carved, by the wash and dripping from the central marshes. The three zones have always been fairly distinct in every part of Africa that I have known, from Mozambique round to the mouth of the Congo, though in a few places the mountain zone comes down close to the sea.

From Benguela I had to trek for six days, often taking advantage of the moon to trek at night as well, before I saw a trace of water on the surface of the rivers, and nine days before running water was found, though I was trekking in the middle of the wet season. There are one or two dirty wet places, nauseous with sulphur, but all drinking-water for man or ox must be dug for in the beds of the sand rivers, and sometimes you have to dig twelve feet down before the sand looks damp. It is a beautiful land of bare and rugged hills, deeply scarred by weather, and full of the wild and brilliant colors—the violet and orange—that bare hills always give. But the oxen plod through it as fast as possible, really almost hurrying in their eagerness for a long, deep drink. Yet the district abounds in wild animals, not only in elands and other antelopes, which can withdraw from their enemies into deserts drier than teetotal States and can do without a drink for days together. But there are other animals as well, such as lions and zebras and buffaloes, which must drink every day or die. Somewhere, not far away, there must be a “continuous water-supply,” as a London County Councillor would say, and hunters think it may be the Capororo or Korporal or San Francisco, only eight hours south of the road, where there is always real water and abundance of game. A thirsty lion would easily take his tea there in the afternoon and be back in plenty of time to watch for his dinner along the road.

Lions are increasing in number throughout the district, and, I believe, in all Angola, though they are still not so common as leopards. Certainly they watch the road for dinner, and all the way from Benguela to Bihé you have a good chance of hearing them purring about your wagon any night. Sometimes, then, you may find a certain satisfaction in reflecting that you are inside the wagon and that twenty oxen or more are sleeping around you, tied to their yokes. An ox is a better meal than a man, but to men as well as to oxen the lions are becoming more dangerous as the wilder game grows scarcer. A native, from the wagon which crossed the Cuando just after mine, was going down for water in the evening, when a lion sprang on him and split the petroleum-can with his claw. The boy had the sense to beat his cup hard against the tin, and the monarch of the forest was so disgusted at the noise that he withdrew; but few boys are so quick, and many are killed, especially in the mountain zone, about one hundred miles from the coast.

I think it is ten years ago now that one of the Brothers of the Holy Spirit was walking in the mission garden at Caconda in the cool of the evening, meditating vespers or something else divine, when he looked up and saw a great lion in the path. Instead of making for the nearest tree, he had the good sense to fall on his knees, and so he went to death with dignity. And on one of the nights when I was encamped near the convent six lions were prowling round it. Vespers were over, but it was a pleasure to me to reflect how much better prepared for death the Brothers were than I.

It is very rarely that you have the luck to see a lion, even where they abound. They are easily hidden. Especially in a country like this, covered with the tawny mounds and pyramids of the white ant, you may easily pass within a few yards of a whole domestic circle of lions without knowing it. Nor will they touch an armed white man unless pinched with hunger. Yet, in spite of all travellers’ libels, the lion is really the king of beasts, next to man. You have only to look at his eye and his forearm to know it. I need not repeat stories of his strength, but one peculiarity of his was new to me, though perhaps familiar to most people. A great hunter told me that when, with one blow of his paw, a lion has killed an ox, he will fasten on the back of the neck and cling there in a kind of ecstasy for a few seconds, with closed eyes. During that brief interval you can go quite close to him unobserved and shoot him through the brain with impunity.

I found the most frequent spoor of lions in a sand river among the mountains, about a week out from Benguela. The country there is very rich in wild beasts—Cape buffalo, many antelopes, and quagga (or Burchell’s zebra, as I believe they ought to be called, but the hunters call them quagga).

I was most pleased, however, to find upon the surface of the sand river the spoor of a large herd of elephants which had passed up it the night before. It was difficult to make out their numbers, for they had thrust their trunks deep into the sand for water, and having found it, they evidently celebrated the occasion with a fairy revel, pouring the water over their backs and tripping it together upon the yellow sands. But when they passed on, it was clear that the cows and calves were on the right, while the big males kept the left, and probably forced the passages through the thickest bush. A big bull elephant’s spoor on sand is more like an embossed map of the moon with her mountains and valleys and seas than anything else I can think of. A cow’s footprint is the map of a simpler planet. And the calf’s is plain, like the impression of a paving-hammer, only slightly oval.

There was no nasty concealment about that family. The path they had made through the forest was like the passage of a storm or the course of a battle. They had broken branches, torn up trees, trampled the grass, and snapped off all the sugary pink flowers of the tall aloes, which they love as much as buns in the Zoo. So to the east they had passed away, open in their goings because they had nothing to fear—nothing but man, and unfortunately they have not yet taken much account of him. The hunters say that they move in a kind of zone or rough circle—from the Upper Zambesi across the Cuando into Angola and the district where they passed me, and so across the Cuanza northward and eastward into the Congo, and round towards Katanga and the sources of the Zambesi again. The hunters are not exactly sure that the same elephants go walking round and round the circle. They do not know. But a prince might very profitably spend ten years in following an elephant family round from point to point of its range—profitably, I mean, compared to his ordinary round of royal occupations.

I must not stay to tell of the birds—the flamingoes that pass down the coast, so high that they look no more than geese; the eagles, vultures, and hawks of many kinds; the parrots, few but brilliant; the metallic starling, of two species at least, both among the most gorgeous of birds; the black-headed crane and the dancing crane whose crest is like Cinderella’s fan, full-spread and touched with crimson; the many kinds of hornbill, including the bird who booms all night with joy at approaching rain; the great bustard, which the Boers in their usual slipshod way called the pau or peacock, simply because it is big, just as they call the leopard a tiger and the hyena a wolf. Nor must I tell of the guinea-fowl and francolins, or of the various doves, one of which begins with three soft notes and then runs down a scale of seven minor tones, fit to break a mourner’s heart; nor of the aureoles and the familiar bird that pleases his wives by growing his tail so long he can hardly hover over the marshes; nor even of our childhood’s friend, the honey-guide, whose cheery twitter may lead to the wild bees’ nest, but leads just as cheerily to a python or a lion asleep. I cannot speak of these, though I feel there is the making of a horrible tract in that honey-guide.

When you have climbed the mountains—in one place the wagon crawls over a pass or summit of close upon five thousand feet—you gradually leave the big game (except the lions) and the most brilliant of the birds behind. But the deer become even more plentiful in places. The road is driving them away, as it has driven the natives, and for the same reason. But within a few hours of the road you may find them still—the beautiful roan antelope, the still more beautiful koodoo, the bluebock, the lechwe, the hartebeest (and, I believe, the wildebeest, or gnu, as well), the stinking water-buck, the reedbuck, the oribi, and the little duiker, or “diver,” called from its way of leaping through the high grass and disappearing after each bound. It is fine to see any deer run, but there can be few things more delightful than to watch the easy grace of a duiker disappearing in the distance after you have missed him.

Caconda is, in every sense, the turning-point of the journey; first, because the road, after running deviously southeast, here turns almost at right angles northeast on its way to Bihé; secondly, because Caconda marks the entire change in the character of the scenery from mountains to the great plateau of forest and marshy glades. And besides, Caconda is almost the one chance you have of seeing human habitations along the whole course of the journey of some four hundred and fifty miles. The large native town has long since disappeared, though you can trace its ruins; but about five miles south of the road is a rather important Portuguese station of half a dozen trading-houses, a church—only in its second year, but already dilapidated—and a fort, with a rampart, ditch, a toy cannon, and a commandant who tries with real gravity to rise above the level of a toy. Certainly his situation is grave. The Cunyami, who ate up the Portuguese force on the Cunene in September of 1904, have sent him a letter saying they mean next to burn him and his fort and the trading-houses too. He has under his command about thirty black soldiers and a white sergeant; and he might just as well have thirty black ninepins and a white feather. He impressed me as about the steadiest Portuguese I had yet seen, but no wonder he looked grave.

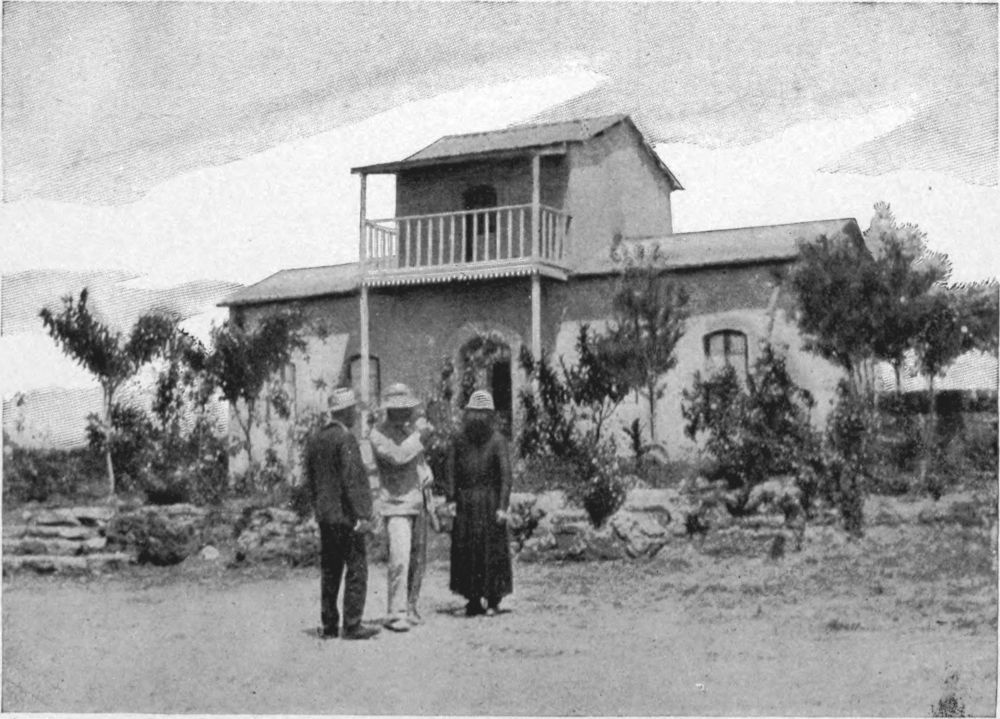

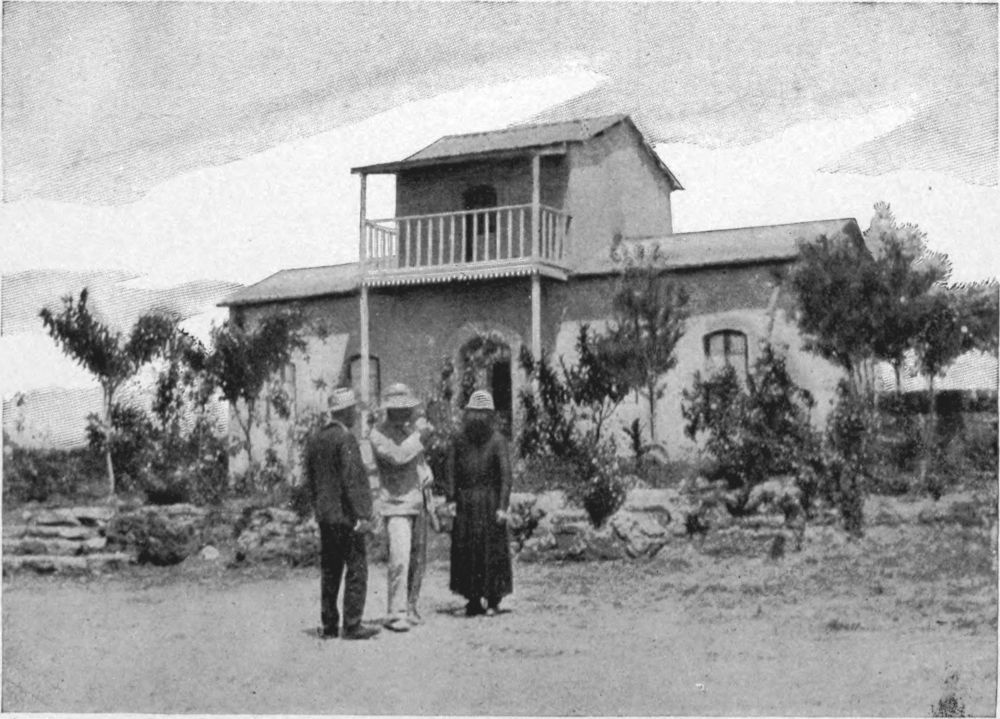

He is responsible, further, for the safety of the Catholic mission, which stands close beside the wagon track itself, overlooking a wide prospect of woodland and grass which reminds one of the view over the Weald of Kent from Limpsfield Common or Crockham Hill. The mission has a tin-roofed church, a gate-house, cells for the four Fathers and five Brothers, dormitories for a kind of boarding-school they keep, excellent workshops, a forge, and a large garden, where the variety of plants and fruits shows what the natives might do but for their unalterable belief that every new plant which comes to maturity costs the life of some one in the village.

CATHOLIC MISSION AT CACONDA

Though under Portuguese allegiance and drawing money from the state, all the Fathers and Brothers were French or Alsatian. The superior was a blithe and energetic Norman, who probably could tell more about Angola and its wildest tribes than any one living. But to me, caution made him only polite. The Fathers are said to maintain that acrid old distinction between Catholic and Protestant—not, one would have thought, a matter of great importance—and in the past they have shown much hostility to all other means of enlightening the natives except their own. But things are quieter just now, and over the whole mission itself broods that sense of beauty and calm which seems almost peculiar to Catholicism. One felt it in the gateway with its bell, in the rooms, whitewashed and unadorned, in the banana-walk through the garden, in the workshops, and even under that hideous tin roof, when some eighty native men and women knelt on the bare, earthen floor during the Mass at dawn.

It is said, but I do not know with what truth, that the Fathers buy from the slave-traders all the “boys” whom they bring up in the mission. The Fathers themselves steadily avoided the subject in conversing with me, but I think it is very probable. About half a mile off is a Sisters’ mission, where a number of girls are trained in the same way. When the boys and girls intermarry, as they generally do, they are settled out in villages within sight of the mission. I counted five or six such villages, and this seems to show, though it does not prove, that most of the boys and girls came originally from a distance, or have no homes to return to. On the whole, I am inclined to believe that but for slavery the mission’s work must have taken a different form. But why the Fathers should be so cautious about confessing it I do not know, unless they are afraid of being called supporters of the slave-trade because they buy off a few of its victims, and so might be counted among its customers.

From Caconda it took me only three weeks with the wagon to reach the Bihé district, which, I believe, was a record for the wet season. There are five rivers to cross, all of them difficult, and the first and last—the Cuando and the Kukema—dangerous as well. The track also skirts round the marshy source of other great watercourses, and it was with delight that I found myself at the morass which begins the great river Cunene, and, better still, at a little “fairy glen” of ferns and reeds where the Okavango drips into a tiny basin, and dribbles down till it becomes the great river which fills Lake Ngami—Livingstone’s Lake Ngami, so far away, on the edge of Khama’s country!

The wagon had, besides, to struggle across many of those high, upland bogs which are the terror of the transport-rider in summer-time. The worst and biggest of these is a wide expanse something like an Irish bog or a wet Salisbury Plain, which the Portuguese call Bourru-Bourru, from the native Vulu-Vulu. It is over five thousand feet above the sea, and so bare and dreary that when the natives see a white man with a great bald head they call it his Vulu-Vulu. It was almost exactly midsummer there when I crossed it, and I threw no shadow at noon, but at night I was glad to cower over a fire, with all the coats and blankets I had got, while the mosquitoes howled round me as if for warmth.

Two points of history I must mention as connected with this part of my journey. The day after I crossed the Calei I came, while hunting, to a rocky hill with a splendid view over the valley, only about a mile from the track. On the top of the hill I found the remains of ancient stone walls and fortifications—a big circuit wall of piled stones, an inner circle, or keep, at the highest point, and many cross-walls for streets or houses. The whole was just like the remains of some rude mediæval fortress, and it may possibly have been very early Portuguese. More likely, it was a native chief’s kraal, though they build nothing of the kind now. Among the natives themselves there is a vague tradition of a splendid ancient city in this region, which they remember as “The Mountain of Money.” Possibly this was the site, and it is strange that no Boers or other transport-riders I met had ever seen the place.

The other point comes a little farther on—about three days after one crosses the Cunughamba. It is the place by the roadside where, three years ago, the natives burned a Portuguese trader alive and made fetich-medicine of his remains. It happened during the so-called “Bailundu war” of 1902, to which I have referred before. On the spot I still found enough of the poor fellow’s bones to make any amount of magic. But if bones were all, I could have gathered far more in the deserted village of Candombo close by. Here a great chief had his kraal, surrounded by ancient trees, and clustered round one of the mightiest natural fortresses I have ever seen. It rises above the trees in great masses and spires of rock, three or four hundred feet high, and in the caves and crevasses of those rocks, now silent and deserted, I found the pitiful skeletons of the men, women, and children of all the little tribe, massacred in the white man’s vengeance. Whether the vengeance was just or unjust I cannot now say. I only know that it was exacted to the full.