V

THE AGENTS OF THE SLAVE-TRADE

The few English people who have ever heard of Bihé at all probably imagine it to themselves as a largish town in Angola famous for its slave-market. Nothing could be less like the reality. There is no town, and there is no slave-market. Bihé is a wide district of forest and marsh, part of the high plateau of interior Africa. It has no mountains and no big rivers, except the Cuanza, which separates it from the land of the Chibokwe on the east. So that the general character of the country is rather indistinctive, and you might as well be in one part of it as another. In whatever place you are, you will see nothing but the broad upland, covered with rather insignificant trees, and worn into quiet slopes by the action of the water, which gathers in morasses of long grass, hidden in the midst of which runs a deep-set stream. Except that it is well watered, fairly cool, and fairly healthy, there is no great attraction in the region. There are a good many leopards and a few wandering lions in the north. Hippos come up the larger streams to breed, and occasionally you may see a buck or two. But it is a poor country for beasts and game, and poor for produce too, though the orange orchards and strawberry-beds at the mission stations show it is capable of better things. On the whole, the impression of the country is a certain want of character. Often while I have been plodding through woods looking over a grassy valley I could have imagined myself in Essex, except that here there are no white roads and no ancient villages. The whole scene is so unlike the popular idea of tropical Africa that it is startling to meet a naked savage carrying a javelin, and almost shocking to meet a lady with only nine inches of dress.

There is no town and no public slave-market. The Portuguese fort at Belmonte, once the home of that remarkable man and redoubtable slave-trader, Silva Porto, and the scene of his rather splendid suicide in 1890, may be taken as the centre of the district. But there are only two or three Portuguese stores gathered round it, and scattered over the whole country there are only a very limited number of other trading-houses, the largest being the headquarters of the Commercial Company of Angola, established at Caiala, one day’s journey from the fort. The trading-houses are, I think, without exception, worked by slave labor, as are the few plantations of sweet-potato for the manufacture of rum, which, next to cotton cloth, is the chief coinage in all dealings with the natives. The exchange from the native side consists chiefly of rubber, oxen, and slaves, a load of rubber (say fifty to sixty pounds), an ox, and a young slave counting as about equal in the recognized currency. In English money we might put the value at £9.

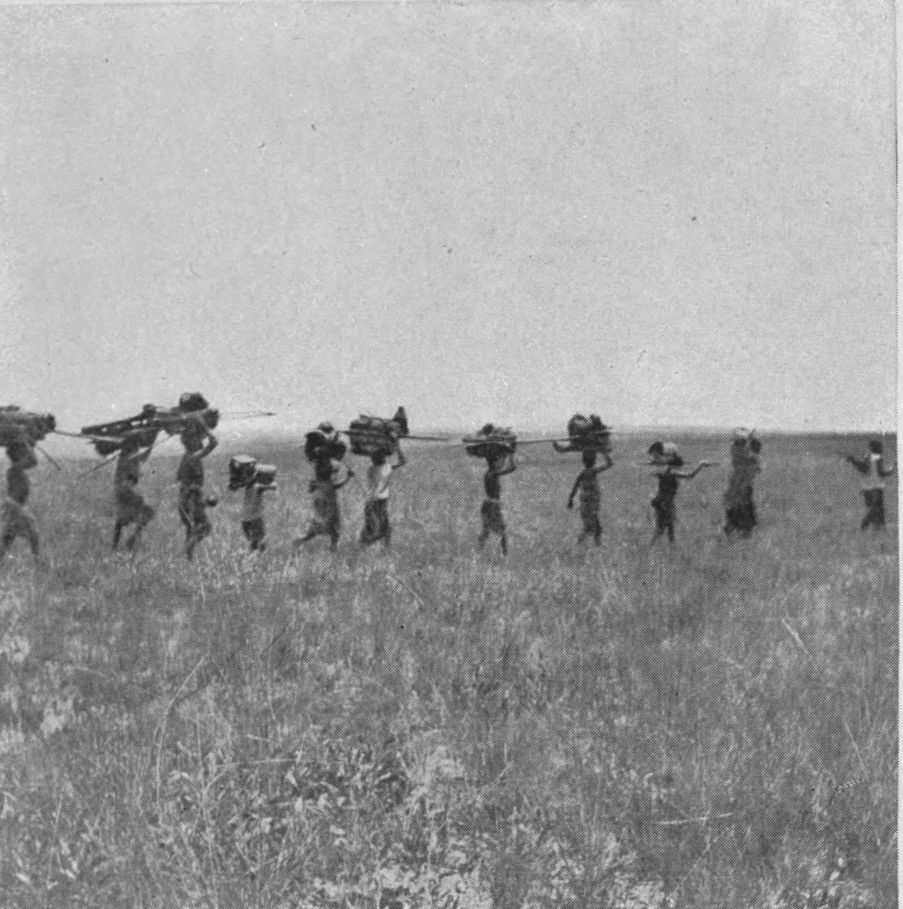

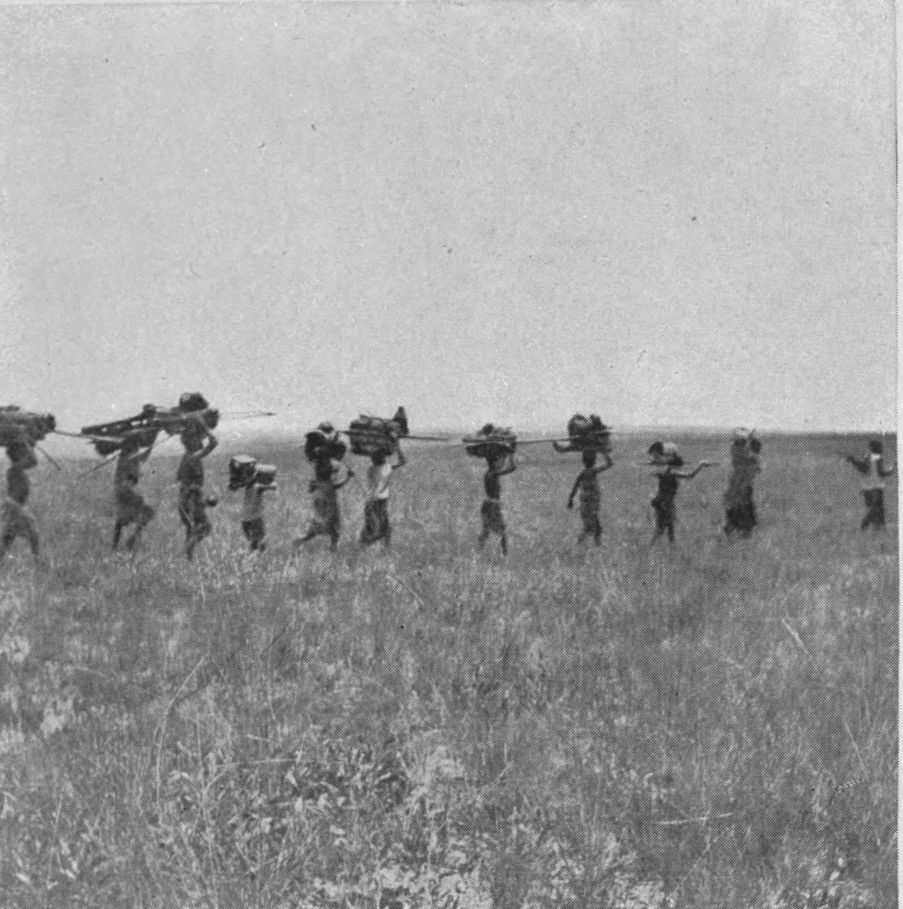

CARRIERS ON THE MARCH

It is through these trading-houses that the slave-trade has hitherto been chiefly conducted, and if you want slaves you can buy them readily from any of the larger houses still. But the Bihéans have themselves partly to blame for the ill repute of their country. They are born traders, and will trade in anything. For generations past, probably long before the Portuguese established their present feeble hold upon the country, the Ovimbundu, as they are called, have been sending their caravans of traders far into the interior—far among the tributaries of the Congo, and even up to Tanganyika and the great lakes. Like all traders in Central Africa, they tramp in single file along the narrow and winding foot-paths which are the roads and trade routes of the country. They carry their goods on their heads or shoulders, clamped with shreds of bark between two long sticks, which act as levers. The regulation load is about sixty pounds, but for his own interest a man will sometimes carry double as much. As a rule, they march five or six hours a day, and it takes them about two months to reach the villages of Nanakandundu, which may be taken as the centre of African trade, as it is the central point of the long and marshy watershed which divides the Zambesi from the Congo. For merchandise, they carry with them cotton cloth, beads, and salt, and at present they are bringing out rubber for the most part and a little beeswax. As to slaves, guns, gunpowder, and cartridges are the best exchange for them, owing to the demand for such things among the “Révoltés”—the cannibal and slave-dealing tribes who are holding out against the Belgians among the rivers west of the Katanga district. But the conditions of this caravan slave-trade have been a good deal changed in the last three years, and I shall be able to say more about it after my farther journey into the interior.

As traders, the Bihéans have gained certain advantages. Their Umbundu language almost takes the place in Central West Africa that the Swahili takes on the eastern side. It will carry you fairly well, at all events, along the main foot-paths of trade. They are richer than other tribes, too; they live a little better, they wear rather larger cloths, and get more to eat. But they are naturally despised by neighbors who live by fighting, hunting, fishing, and the manly arts. They are tainted with the softness of trade. In the rising against the Portuguese in 1902, which brought such benefits to all this part of Angola, nearly all of them refused to take any share. They are losing all skill and delight in war. They are almost afraid of their own oxen, and scarcely have the courage to train them. For the wilder side of African life a Bihéan is becoming almost as useless as a board-school boy from Hackney. For skill or sense of beauty in the common arts of metal-work, wood-work, basket-weaving, or ornament, they cannot compare to any of the neighboring tribes. In fact, they are a commercial people, and they pay the full penalty which all commercial peoples have to pay.

Away from the main trade route the country is rather thickly inhabited. The villages lie scattered about in clusters of five or six together. All are strongly stockaded, for custom rather than defence (unless against leopards), and all have rough gates of heavy swinging beams that can be dropped at night, like a portcullis. Most people would say the huts were round; but only the cattle-breeding tribes, like the Ovampos in the south, have round huts. The Bihéan huts are intended to be oblong or square, but as natives have no eye for the straight line, and the roofs are invariably conical, one is easily mistaken. Except to those who have seen nothing better than the filth and grime of English cities, the villages would not appear remarkably clean. They cannot compare for neatness and careful arrangement to the Zulu villages, for instance, nor even to the neighboring Chibokwe. But each family has its separate enclosure, with huts according to its size or the number of the wives, and usually a little patch of garden—for peppers, tomatoes the size of damsons, and perhaps some tobacco. Somewhere in the centre of the enclosures there is sure to be a largish open space with a town hall or public club (onjango). This is much the same in all villages in Central Africa—a pointed, shady roof, supported by upright beams, set far enough apart to admit of entrance on any side. It serves as a parliament-house, a court of justice, a general workshop (especially for metal-workers among the Chibokwe), and for lounge, or place of conversation and agreeable idleness. Perhaps a good club is the best idea we can form of it. It forms a meeting-place for politics, news, chatter, money-making, and games, nor have I ever seen a woman inside.

On the dusty floor a piece of hard ground, three or four inches above the rest of the surface, is usually left as the throne or place of honor for the chief. There he reclines, or sits on a stool six inches high, and exercises the usual royal functions. He is clothed in apparel which one soon comes to recognize as kingly. It is some sort of cap or hat and a shirt. The original owners of both were probably European, but time enough has elapsed to secure them the veneration due to the symbols of established authority, and they are covered with layer upon layer of tradition. Thus arrayed, the chief sits from morning till evening in the very heart of his kingdom and contemplates its existence. Sometimes a criminal case or a dispute about debt comes up for his decision. Then he has the assistance of three elders of the village, and in extreme cases he is supposed to seek the wisdom of the white man at the fort. But the expense of such wisdom is at least equal to its value, and rather than risk the delay, the uncertainty of justice, and the certainty of some contribution to the legal fees in pigs, oxen, or rubber, the villagers usually settle up their own differences more quickly and good-naturedly now than they used, and so out of the strong comes forth sweetness. In the last resort the ancient tests of poison and boiling water are still regarded as final (as, indeed, they are likely to be), and men who have lived long in the country and know it well assure me that those tests are still recommended by the wisdom of the white man at the fort.

Adjoining the public square the chief has his own enclosure, with the royal hut for his wives, who may number anything from four to ten or so, the number, as in all countries, being regulated by the expense. Leaving the politics, law, games, and other occupations of public life to the more strictly intellectual sex, the wives, like the other women of the village, follow the primeval labor of the fields (which, as a rule, are of their own making), and go out at dawn with basket and hoe on their heads and babies wrapped to their backs, returning in the afternoon to pound the meal in wooden mortars, and otherwise prepare the family’s food.

I have had difficulty in finding out why one man is chief rather than another. It is not entirely a matter of blood or of wealth, still less of character. But all these go for something, and the villagers themselves appear to have a certain voice in the selection, though the choice must lie within the bounds of the “blood royal.” Constitutionally, I believe, the same principle holds in the case of the British crown. I have never heard of a disputed succession in an African village, though disputes often arise in the larger tribes, as among the Cunyami, where a very intelligent chief was lately poisoned by his brother, as too peaceable and philosophic for a king. But there is no longer a king or head chief in Bihé. The last was captured over twenty years ago, after a mythical resistance in his umbala or capital of Ekevango, the ancient trees of which can be seen from the American mission at Kamundongo. So he joined the kings in exile, and, I believe, still drags out an existence of memories in the Santiago of Portuguese Guinea. There remain the chiefs of districts, and the headmen of villages, and though, as I have described, their state is hardly to be distinguished from that of royalty, they are generally allowed to live to enjoy it.

But best of all I like a chief in his moments of condescension, when he steps down from his four inches of mud and squats in the level dust with the rest, just to show the young men how games should be played. Chiefs appear to be specially good at the games which take the place of cards and similar leisurely pastimes in European courts. The favorite is a mixture of backgammon and “Archer up.” It is played either on a hewn log or in the dust, and consists in getting a large number of beans through four rows of holes. At first it looks like “go as you please,” but in time, as you watch, certain rules rise out of chaos, and you find that the best player really wins. The best player is nearly always the chief, and I have no doubt he devotes long hours of his magnificent leisure to pondering over the more scientific aspects of the pursuit. In the same way one has heard of European kings renowned for their success at Monte Carlo, baccarat, and bridge.

But, besides the games, the chiefs are the repositories of traditional wisdom, and for this function it is harder to find a parallel among civilized courts. The wisdom is usually expressed in symbolic diagrams upon the dust. In his moments of fatherly instruction the chief will smooth a surface with his hand, and on it trace with his fingers a mystic line—I think it must always be a continuous and unbroken line—which expresses some secret of human existence. Sometimes the design is merely heraldic, as in this conventional figure of a one-headed eagle, which I recommend to the German Emperor for a new flag. But generally there is a hidden significance, not to be detected without superior information. The chief, for instance, will imprint five spots on the sand, and round them trace an interminable line which just misses each spot in turn. The five spots signify the vain ambitions of man, and the line is man’s vain effort ever to reach them. Or again, he will mark nine points with his finger on the sand and trace a line which will surround eight of them and always come back to the ninth, which stands in the centre. Till superior wisdom informed you, probably you would hardly guess that the eight points are the “thoughts” of man, and that the ninth, to which the line always returns, is the end of the whole matter—that no solution of the thoughts of man is ever to be found:

“Earth could not answer, nor the seas that mourn.”

It is surprising to find a philosophy so Omarian so far from Nashipur and Babylon, but there it is.

The Ovimbundu of Bihé, like all the natives in this part of Africa, have also a large stock of proverbs. Out of a number of Umbundu proverbs I have heard, we may take three as pretty fair samples of wisdom: “If you miss, don’t break your bow,” which I like better than the English doggerel of, “Try, try, try again,” or, “A bad carpenter quarrels with his tools”; “Speak of water and the fish are gone,” a proverb that will bear many interpretations, though I think it really means, “Never introduce your donah to your pal”; and, “The lion needs no servant,” which I like best of all, but can find no parallel for among a race so naturally snobbish as ourselves. A variation of the proverb runs, “A pig has no servant, a lion needs none.” I have heard many stories of folk-lore, too—legends or fables of animals, something in the manner of “Uncle Remus.” As that the mole came late and got no tail, or that the hen one day claimed the crocodile for her brother, and all the beasts, under the hippo, assembled to support the crocodile, and all the birds, under the eagle, to support the hen. After long argument the hen demanded whether the crocodile did not spring from an egg like herself. The claim was admitted, and since then the crocodile and the hen have been brother and sister.

More in the character of “Uncle Remus” is the favorite story how the dog became the friend of man. Once upon a time a leopard intrusted a starving dog with the care of her cubs. All went well till a turtle appeared upon the scene and induced the dog to bring out one of the cubs and share it between them, saying she could show the leopard the same cub twice over and persuade her that the whole brood was flourishing. This went on very satisfactorily for some days, the dog and turtle devouring a cub daily, and the dog producing one of the cubs for the leopard’s inspection twice, three times, four times over, as the case demanded. At last only one cub was left alive, and it had to be produced eight or nine times, according to the original number of the litter. Next day there was no cub left at all, and the dog invited the leopard to walk into the den and contemplate her healthy young nursery for herself. No sooner had she entered the cave than the dog bolted for the nearest village, and rushed among the huts, crying, “Man, man, the leopard is coming!” Since which day the dog has never left the village, but has remained the friend of man.

Nearly akin to folk-lore are the quaint sayings and brief stories which sum up the daily experience of a people. Take, for instance, this dilemma, turning on an antipathy which appears to be the common heritage of all mankind: “I go to bury my mother-in-law. The king sends for me to attend his council. If I do not go to the king, he will cut my head off. If I do not bury my mother-in-law, she may come to life. I go to bury my mother-in-law.” More unusual to English ears was the statement made quite seriously in my presence by a young man who was inquiring about the manner of life in England. “If you can buy things there,” he said, “there is no need to marry.” Certainly not; when you can buy meal in a shop, why expose yourself to the annoyance and irritation of keeping wives to sow and gather and pound and sift the mealies for you?

Like all the tribes of this region, the Bihéans are much given to dancing, especially under a waxing moon, and when the dry season is just beginning—say in the end of April. It so happens that the Bihéan dances I have seen have been almost always the dances of children, and they were very pretty. Sometimes a girl is lifted on the hands of a group of children and jumped up and down in that perilous position, while the others dance and sing round her. Sometimes the dance is a kind of “hen and chickens” or “prisoners’ base.” But the prettiest dance I know is the frog dance, in which the children crouch down in rows and leap over the ground, clapping their elbows sharply against their naked sides, with exactly the effect of Spanish castanets, while their hard, bare feet stamp the dust in time. Then they have a game something like “hunt the slipper,” two rows sitting on the ground opposite each other, and tossing about a knotted cloth with their legs. All these dances and games are accompanied by monotonous and violent singing, the words of the song being repeated over and over again. They are generally of the simplest kind, and have no apparent connection with the dance. The song which I heard to the frog dance, for instance, ran: “I am going to my mother in the village. I am going to my mother in the village.”

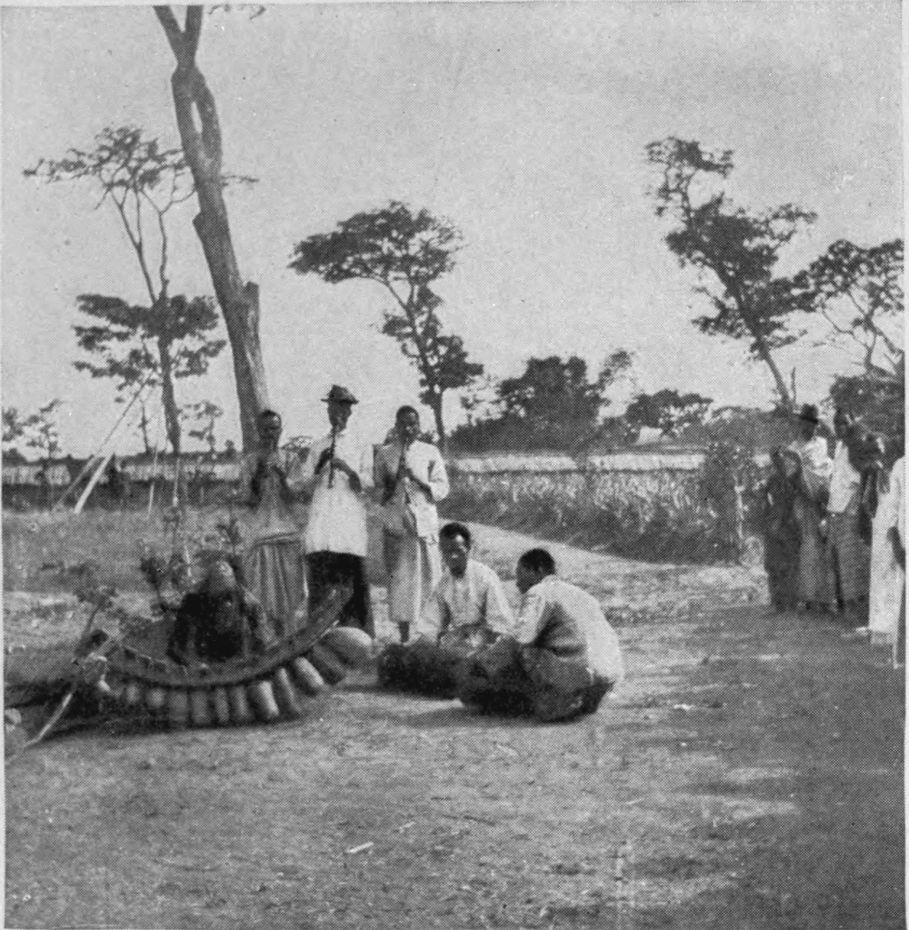

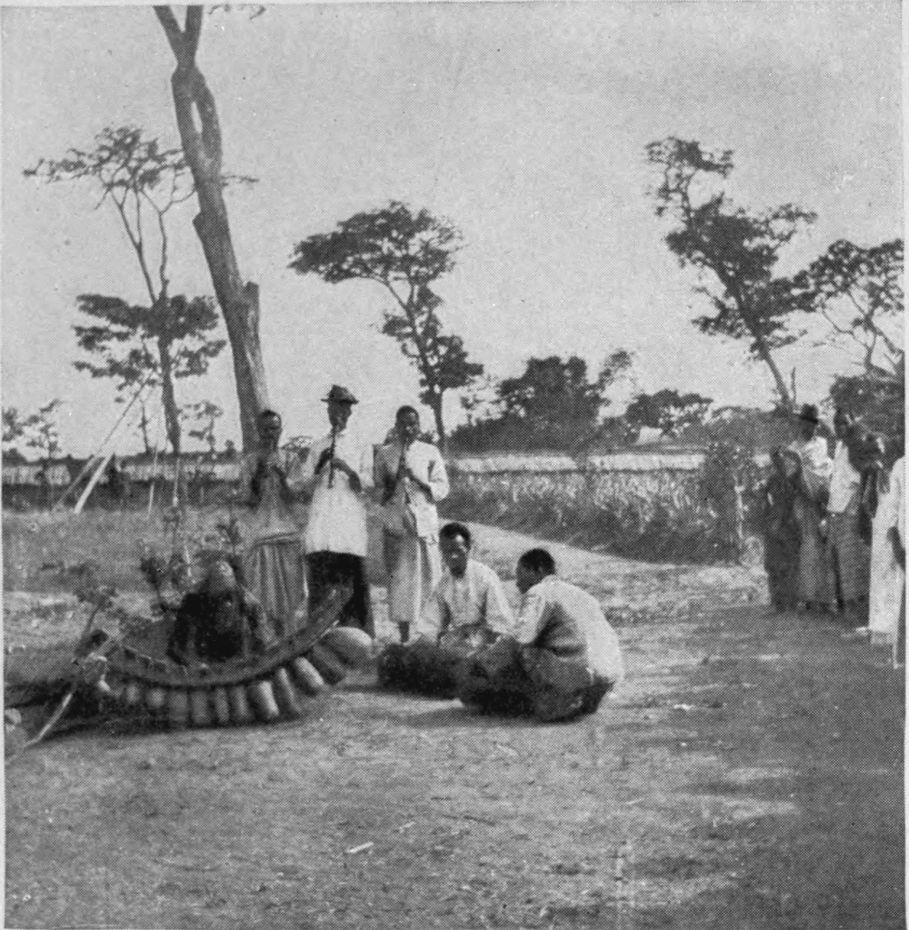

Various musical instruments are used all through this part of Africa, perhaps the simplest being the primeval fiddle. A string of bark is stretched across half a gourd, and made to vibrate with a notched stick drawn to and fro across it. The player holds the gourd against his breastbone, and hisses through his teeth in time to the movement, sometimes adding a few words of song. After an hour or so he thus works himself and his audience up almost to hypnotic frenzy. If this is the simplest instrument, the alimba is the most elaborate. It is a series of wooden slats—twelve or fourteen—attached to a curved framework about six feet long. Behind the slats gourds are fixed as sounding-boards, but the number of gourds does not necessarily correspond to the slats. The player squats in the middle of the curve and strikes the wood with rubber hammers. Though there is no true scale of any kind, the individual notes are often fine and the result very beautiful, especially before the singing begins.

But the true instruments of Central Africa are the ochisanji and the drum. The ochisanji is the primeval piano, a row of iron keys (sometimes two rows) being laid upon a small oblong board, which is covered with carving. The keys are played with the thumbs, and some loose beads or bits of iron at the bottom of the board set up a rattling which, to us, does not improve the music. But it is really a beautiful instrument, and I can well imagine that when a native hears it far from his village he is filled with the same yearning that a Swiss feels at the sound of a cow-horn. It is the common accompaniment to all native songs, the words being spoken to it rather than sung. Nearly all carriers have an ochisanji tied round their necks, and one of my carriers used to sing me a minor song, lamenting his poverty, his loss of an ox, and loss of a lover, and between each verse he put in a sobbing refrain, very musical and melancholy. The ochisanji also is sometimes laid across half a hollow gourd, to improve the tone.

BIHÉAN MUSICIANS

And then there is the drum! The drum is undoubtedly as much the national instrument of Africa as the bagpipe is of Scotland. It is made out of almost anything—the bark of a tree stitched together into a cylinder and covered with goat-skin at each end, or a hollow stump, or even a large gourd will serve. But there is one kind of drum valued above all others—so precious that, when a village owns one, it is kept in a little house all to itself. This drum is shaped just like an old-fashioned carpet-bag, half open, except that the top is longer than the bottom. It measures about four feet high by three feet long, and is about eight inches broad at the bottom, the sides tapering as towards the mouth. The inside is hollowed out with axes, the whole being made of one solid block of wood. Half-way along the sides, near the top or mouth, rough lumps of rubber are fixed, and these are thumped either with a rubber-headed drumstick or with the fist, while a second player taps the wood with a bit of stick. The result is the most overwhelming sound I have heard. I know the war-drum, and I know the glory of the drums in the Ninth Symphony, but I have never known an instrument that had such an effect upon the mind as this African ochingufu. To me it is intensely depressing. At its first throb my heart sinks into my boots. Far from being roused to battle by such a sound, my instinct would be to hide under the blanket. But to the native soul it is truly inspiring. To all their great dances this is the sole accompaniment, and for hour after hour of the night they will keep up its unvaried beat without intermission, one drummer after another taking his turn, while the dance goes on, and from time to time the dancers and the crowd raise their monotonous chant. The invention of this terrible instrument was altogether beyond Bihéan art, though they sometimes imitate the models for themselves. But the greater number of the drums are still imported from the far interior, around the sources of the Zambesi, and they have become a regular article of commerce. Many a time, along the great foot-path of trade, I have seen a carrier bringing down the drum as part of his load from some village hundreds of miles east of Bihé, and I have wondered at the demon of terror and revelry which lay enchanted in that common-looking piece of hollow wood.

But then the whole country is full of other demons, not of revelry, but certainly of terror. At the gates (that is, the narrow gaps in the stockade) of nearly all villages stands a little cluster of sticks with the skulls of antelopes on their tops. Sometimes the sticks are roofed over with a little straw. Sometimes they are tied up with strips of cloth like little flags, or a few bits of broken pot are laid in the shrine and a little meal is scattered around. Often a similar shrine is set up inside the village itself, and where a chief lives in his umbala or capital among the ancient trees it will very likely have developed into a “Kandundu”—the abode of a great magic spirit, who dwells in a kind of cage on the top of a long pole. The worship of the Kandundu is in some vague way connected with a frog, and the spirit is supposed to reveal himself and utter his oracles to the witch-doctor in that form. But if you get a chance of exploring that cage on the palm pole, you generally find no frog, but only greasy rags. The bright point about the Kandundu is that the spirit can become actively benevolent instead of being merely a terror to be averted, like most of the spirits in Africa. The same high praise can also be given to Okevenga, whose name may be connected with the great river Okavango, and who is certainly a benevolent spirit, watching over women, and helping them with their fields, their sowing, and their children.

These are the only two exceptions I have hitherto met with to the general malignity of the spiritual world in this part of Africa. The spirits of the dead are always evil disposed, when they return at all, and they are the common agents of the witchcraft that plays so large a part in village life and is the cause of so much slavery. It is not uncommon for a woman to kill herself in order to haunt her mother-in-law or another wife of whom she is jealous. And it is partly to keep the spirit quiet for the year or so before it gradually fades away into nothingness that poles surmounted by the skulls of oxen are set above a grave. Partly also this is to display the wealth of the family, which could afford to kill an ox or two at the funeral feast; just as in England the mass of granite heaped upon a tomb is intended rather to establish the respectability of the deceased than to secure his repose.

Slavery exists quite openly throughout Bihé in the three forms of family slavery among the natives themselves, domestic slavery to the Portuguese traders, and slavery on the plantations. The purchase of slaves is rendered easier by certain native customs, especially by the peculiar law which gives the possession of the children to the wife’s brother, even during the lifetime of both parents. The law has many advantages in a polygamous country, and the parents can redeem their children and make them their own property by various payments, but, unless the children are redeemed, the wife’s brother can claim them for the payment of his own debts or the debts of his village. I think this is chiefly done in the payment of family debts for witchcraft, and I have seen a case in which, for a debt of that kind, a mother has been driven to pawn her own child herself. Her brother had murdered her eldest boy, and, going into the interior to trade, had died there. Of course his wives and other relations charged her with witchcraft through her murdered boy’s spirit, and she was condemned to pay a fine. She had nothing to pay but her two remaining children, and as the girl was married and with child, she was unwilling to take her. So she pawned her little boy to a native for the sum required, though she knew he would almost certainly be sold as a slave to the Portuguese long before she could redeem him, and she would have no chance of redress.

In that particular case, which happened recently, a missionary, who knew the boy, advanced an ox in his place; but the missionary’s intervention was, of course, entirely accidental, and the facts are only typical of the kind of thing that is repeatedly happening in places where there is no one to help or to know.

In a village in the northwest of Bihé I have seen a man—the headman of the place—who has been gradually tempted on by a Portuguese trader till he has sold all his children and all the other relations in his power for rum. Last of all, one morning at the beginning of this winter (1905), he told his wife to smarten herself up and come with him to the trader’s house. She appears to have been a particularly excellent woman, of whom he was very fond. Yet when they arrived at the store he received a keg of rum and went home with it, leaving his wife as the trader’s property.

In the same district I met a boy who told me how his father was sold in the middle of last January. They were slaves to a native named Onbungululu in the village of Chariwewa, and his father, in company with twenty other of the slaves, was sold to a certain Portuguese trader, who acts on behalf of the “Central Committee of Labor and Emigration,” and was draughted quietly away through the bush for the plantations in San Thomé.

To show how low the price of human beings will run, I may mention a case that happened in January, 1905, on the Cuanza, just over the northeast frontier of Bihé. I think I noticed in an earlier chapter that there was much famine there last winter, and so it came about that a woman was sold for forty yards of cloth and a pig (cloth being worth about fourpence a yard), and was brought into Bihé by the triumphant purchaser.

But that was an exception, and the following instance of the slave-trader’s ways is more typical. Last summer a Portuguese, who is perhaps the most notorious and reckless slave-trader now living in Bihé, and whose name is familiar far in the interior of Africa, sent a Bihéan into the southern Congo with orders to bring out so many slaves and with chains to bind them. As the Bihéan was returning with the slaves, one of them escaped, and the trader demanded another slave and three loads of rubber as compensation. This the Bihéan has now paid, but in the mean time the trader’s personal slaves have attacked and plundered his village. The trader himself is at present away on his usual business in the remote region of the Congo basin called Lunda, and it is thought his return is rather doubtful; for the “Révoltés” and other native tribes in those parts accuse him of selling cartridges that will not fit their rifles. But he appears to have been flourishing till quite lately, for the natives in the village where I am staying say that he has sent out a little gang of seven slaves, which passed down the road only the day before yesterday, on their way to San Thomé.

But about that road, which has been for centuries the main slave route from the interior to the Portuguese coast, I shall say more in my next letter, when I have myself passed up and down it for some hundreds of miles and had an opportunity of seeing its present condition.