VI

THE WORST PART OF THE SLAVE ROUTE

I was going east along the main trade route—the main slave route—by which the Bihéans pass to and fro in their traffic with the interior. It is but a continuation of the track from Benguela, on the coast, through the district of Bihé, and it follows the long watershed of Central Africa in the same way. The only place where that watershed is broken is at the passage of the Cuanza, which rises far south of the bank of high ground, but has made its way northward through it at a point some three days’ journey east of the Bihéan fort at Belmonte, and so reaches the sea on the west coast, not very far below Loanda.

It forms the frontier of Bihé, dividing that race of traders from the primitive and savage tribes of the interior. But on both sides along its banks and among its tributaries you find the relics of other races of very different character from the Bihéans—the Luimbi, whose women still wear the old coinage of white cowry-shells in their hair, and the Luchazi, who support their loads with a strap round their foreheads, like the Swiss, and whose women dress their hair with red mud, and carry their babies straddled round the hip instead of round the back.

Going eastward along this pathway into the interior, I had reached the banks of the Cuanza one evening towards the end of the wet season. It had been raining hard, but at sunset there was a sullen clear which left the country steaming with damp. On my left I could hear the roar of the Cuanza rapids, where the river divides among rocky islands and rushes down in breakers and foam. And far away, across the river’s broad valley, I could see the country into which I was going—straight line after line of black forest, with the mist rising in pallid lines between. It was like a dreary skeleton of the earth.

CROSSING THE CUANZA

Such was my first sight of “the Hungry Country”—that accursed stretch of land which reaches from just beyond the Cuanza almost to the Portuguese fort at Mashiko. How far that may be in miles I cannot say exactly. A rapid messenger will cover the distance in seven days, but it took me nine, and it takes most people ten or twelve. My carriers had light loads, and in spite of almost continuous fevers and poisoned feet we went fast, walking from six till two or even four o’clock without food, so that, even allowing for delays at the deep morasses and rivers and the long climbs up the forest hills, I think we cannot have averaged less than twenty miles a day, and probably we often made twenty-five. I should say that the distance from the Cuanza to Mashiko must be somewhere about two hundred and fifty miles, and it is Hungry Country nearly the whole way.

Still less is it certain how far the district extends in breadth from north to south. I have often looked from the top of its highest uplands, where a gap in the trees gave me a view, in the hope of seeing something beyond. But, though the hill might be six thousand feet above the sea, I could never get a sight of anything but forest, and still more forest, till the waves of the land ended in a long, straight line of blue—almost as straight and blue as the sea—and nothing but forest all the way, with not a trace of man. Yet the whole country is well watered. Deep and clear streams run down the middle of the open marshes between the hills. For the first day or two of the journey they flow back into the Cuanza basin, but when you have climbed the woody heights beyond, you find them running north into the Kasai, that great tributary of the Congo, and south into the Lungwebungu or the Luena, the tributaries of the Zambesi. At some points you stand at a distance of only two days’ journey from the Kasai and the Lungwebungu on either side, and there is water flowing into them all the year round. In Africa it is almost always the want of water that makes a Hungry Country, but here the rule does not hold.

At first I thought the character of the soil was sufficient reason for the desert. Except for the black morasses, it is a loose white sand from end to end. The sand drifts down the hills like snow, and banks itself up along any sheltered or level place, till as you plod through it hour after hour, almost ankle-deep, while your shadow gradually swallows itself up as the sun climbs the sky, your only thought becomes a longing for water and a longing for one small yard of solid ground. The trees are poor and barren, and I noticed that the farther I went the soft joints of the grasses, which ought to be sweet, became more and more bitter, till they tasted like quinine.

This may be the cause of another thing I noticed. All living creatures in this region are crazy for salt, just like oxen on a “sour veldt.” Salt is far the best coinage you can take among the Chibokwe. I do not mean our white table-salt. They reject that with scorn, thinking it is sugar or something equally useless; but for the coarse and dirty “bay-salt” they will sell almost anything, and a pinch of it is a greater treat to a child than a whole bride-cake would be in England.

I have tested it especially with the bees that swarm in these forests and produce most of the beeswax that goes to Europe. I first noticed their love of salt when I salted some water one afternoon in the vain hope of curing the poisoned sores on my feet. In half an hour the swarms of bees had driven me from my tent. I was stung ten times, and had to wait about in the forest till the sun set, when the bees vanished, as by signal.

Another afternoon I tested them by putting a heap of sugar, a paper smeared with condensed milk, and a bag of salt tightly wrapped up in tar-paper side by side on the ground. I gave them twenty minutes, and then I found nothing on the sugar, five flies on the milk, and the tar-paper so densely covered with bees that they overlapped one another as when they swarm. For want of anything better, they will fight over a sweaty shirt in the same way; and once, by the banks of a stream, they sent all my carriers howling along the path by creeping up under their loin-cloths. The butterflies seek salt also. If you spread out a damp rag anywhere in tropical Africa, you will soon have brilliant butterflies on it. But if you add a little salt in the Hungry Country, the rag will be a blaze of colors, unless the bees come and drive the butterflies off.

As I said, the natives feel the longing too. Among the Chibokwe, the women burn a marsh-grass into a potash powder as a substitute; and if a native squats down in front of you, puts out a long, pink tongue and strokes it appealingly with his finger, you may know it is salt he wants. The scarcity has become worse since the Belgians, following their usual highwayman methods, have robbed the natives of the great salt-pans in the south of the Congo State and made them a trade monopoly.

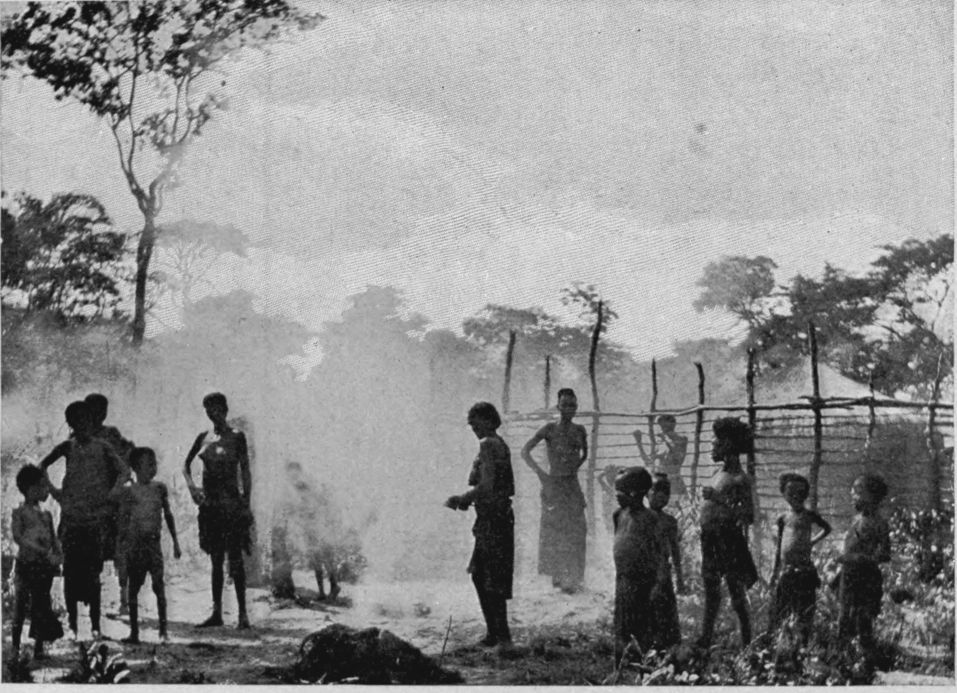

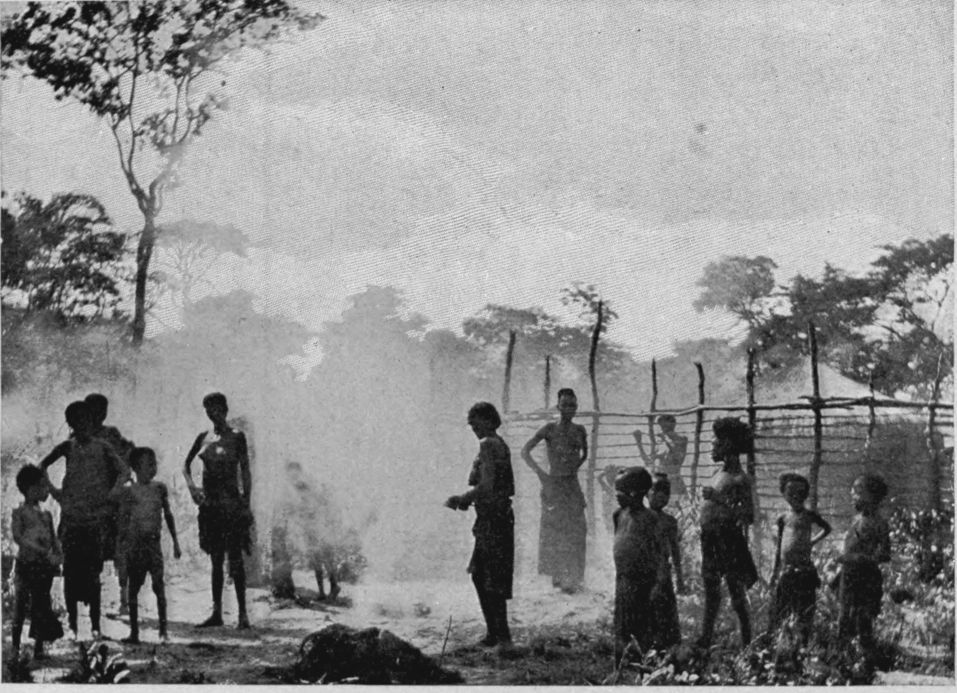

NATIVES BURNING GRASS FOR SALT

In the character of the soil, then, there seemed to be sufficient reason for the name of the country, and I should have been satisfied with it but for distinct evidences that a few spots along the path have been inhabited not so very long ago. Here and there you come upon plants which grow generally or only on the site of deserted villages or fields; such as the atundwa—a plant with branching fronds that smell like walnut leaves. It yields a fruit whose hard and crimson case just projects from the ground and holds a gray bag of seeds, very sour, and almost as good to eat or drink as lemons. But still more definite is the evidence of travellers, like the missionary explorer Mr. Arnot, who first traversed the country over twenty years ago, and has described to me the villages he found there then. There was, for instance, the large Chibokwe town of Peho, which was built round the head of a marsh close upon the main path some two or three days west of Mashiko. You will still find the place marked, about the size of London, on any map of Angola or Africa, but I have looked everywhere for it along the route in vain. A Portuguese once told me he thought it was a few days’ journey north of his house near Mashiko. But he was wrong. The whole place has entirely disappeared, and has less right than Nineveh to a name on a modern map.[1]

The Chibokwe have a custom of destroying their villages and abandoning the site whenever a chief dies, and this in itself is naturally very puzzling to all geographers. But I think it hardly explains the utter abandonment of the Hungry Country. It is commonly supposed that no wild animals will live in the region, but that is not true, either. Many times, when I have wandered away from the foot-path, I have put up various antelopes—lechwe and duikers—and beside the marshes in the early morning I have seen the fresh spoor of larger deer, as well as of porcupines and wart-hogs. Cranes are fairly common, and green parrots very abundant. Almost every night one hears the leopards roar. “Roar” is not the word: it is that deep note of pleasurable expectancy that they sound a quarter of an hour before feeding-time at the Zoo, and they would not make that noise if there was nothing in the country to eat. All these reasons put together drive me unwillingly to think there may be some truth in the native belief that the whole land has been laid under a curse which will never be removed. As I write, the rumor reaches us that the basin of the Zambesi and all its tributaries have just been awarded to Great Britain, so that nearly the whole of the Hungry Country will come under English rule. It is important for England, therefore, that the curse should be forgotten, and in time it may be. All I know for certain is that undoubtedly a curse lies upon the country now.[2]

There are two ferries over the Cuanza, one close under the Portuguese fort, the other a comfortable distance up-stream, well out of observation. It is a typically Portuguese arrangement. The Commandant’s duty is to stop the slave-trade, but how can he be expected to see what is going on a mile or so away! Even as you come down to the river, you find slave-shackles hanging on the bushes. You cross the stream in dugout canoes, running the chance of being upset by one of the hippos which snort and pant a little farther up. You enter the forest again, and now the shackles are thick upon the trees. This is the place where most of the slaves, being driven down from the interior, are untied. It is safe to let them loose here. The Cuanza is just in front, and behind them lies the long stretch of Hungry Country, which they could never get through alive if they tried to run back to their homes. So it is that the trees on the western edge of the Hungry Country bear shackles in profusion—shackles for the hands, shackles for the feet, shackles for three or four slaves who are clamped together at night. The drivers hang them up with the idea of using them again when they return for the next consignment of human merchandise; but, as a rule, I think, they find it easier to make new shackles as they are wanted.

A shackle is easily made. A native hacks out an oblong hole in a log of wood with an axe; it must be big enough for two hands or two feet to pass through, and then a wooden pin is driven through the hole from side to side, so that the hands or feet cannot stir until it is drawn out again. The two hands or feet do not necessarily belong to the same person. You find shackles of various ages—some quite new, with the marks of the axe fresh upon them, some old and half eaten by ants. But none can be very old, for in Africa all dead wood quickly disappears, and this is a proof that the slave-trade did not really end after the war of 1902, as easy-going officials are fond of assuring us.

When I speak of the shackles beside the Cuanza, I do not mean that this is the only place where they are to be found. You will see them scattered along the whole length of the Hungry Country; in fact, I think they are thickest at about the fifth day’s journey. They generally hang on low bushes of quite recent growth, and are most frequent by the edge of the marshes. I cannot say why. There seems to be no reason in their distribution. I have been assured that each shackle represents the death of a slave, and, indeed, one often finds the remains of a skeleton beside a shackle. But the shackles are so numerous that if the slaves died at that rate even slave-trading would hardly pay, in spite of the immense profit on every man or woman who is brought safely through. It may often happen that a sick slave drags himself to the water and dies there. It may be that some drivers think they can do without the shackles after four or five days of the Hungry Country. But at present I can find no satisfactory explanation of the strange manner in which the shackles are scattered up and down the path. I only know that between the Cuanza and Mashiko I saw several hundreds of them, and yet I could not look about much, but had to watch the narrow and winding foot-path close in front of me, as one always must in Central Africa.

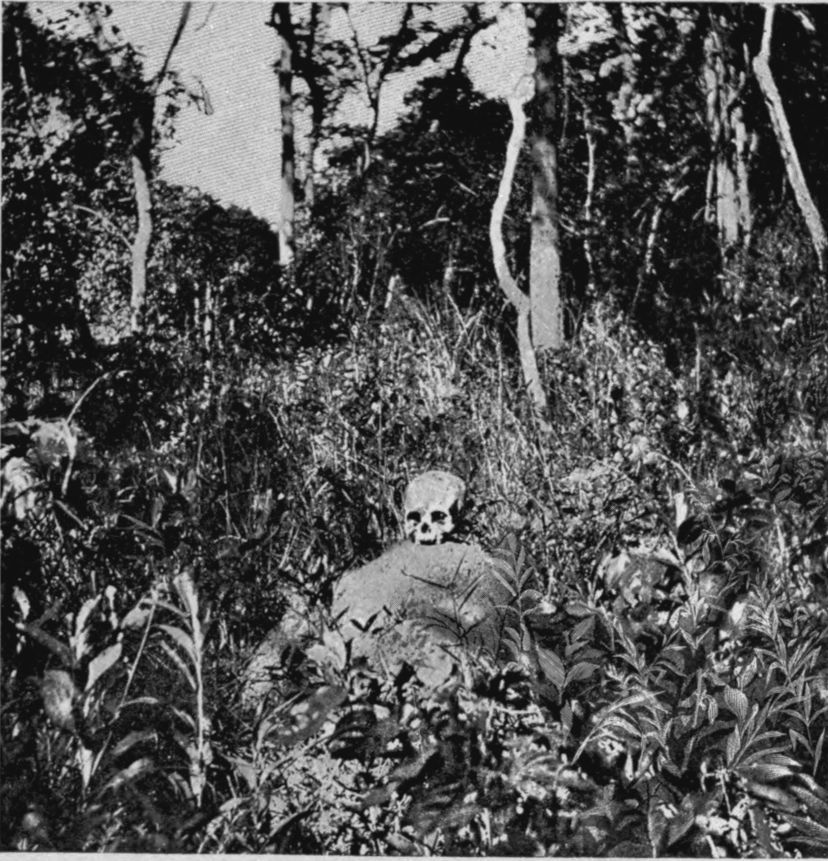

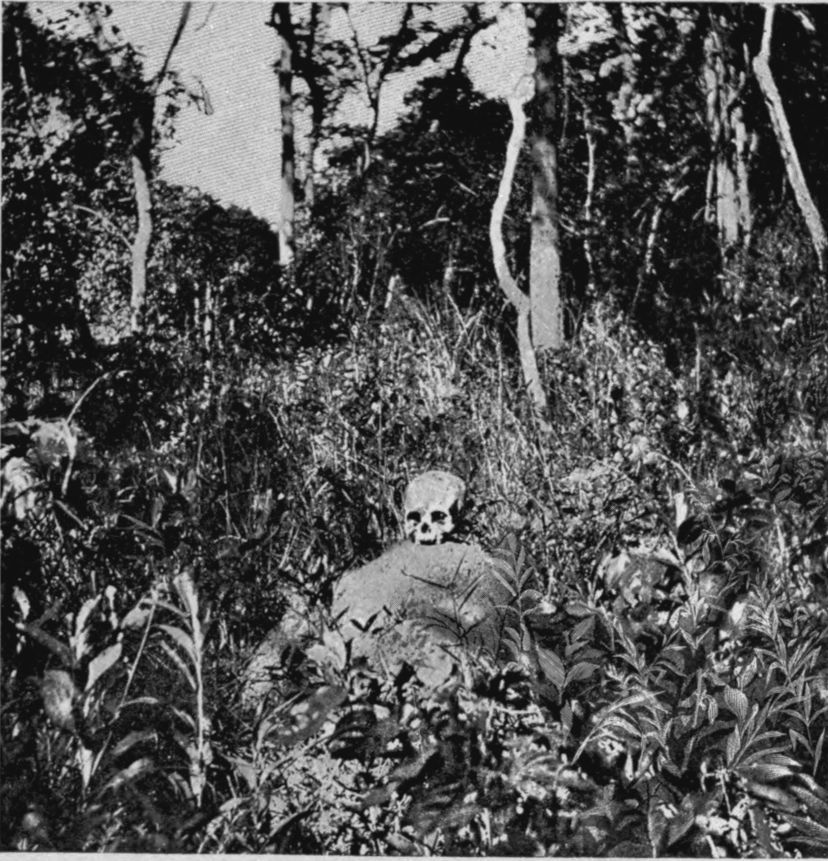

SKELETON OF SLAVE ON A PATH THROUGH THE HUNGRY COUNTRY

That path is strewn with dead men’s bones. You see the white thigh-bones lying in front of your feet, and at one side, among the undergrowth, you find the skull. These are the skeletons of slaves who have been unable to keep up with the march, and so were murdered or left to die. Of course the ordinary carriers and travellers die too. It is very horrible to see a man beginning to break down in the middle of the Hungry Country. He must go on or die. The caravan cannot wait for him, for it has food for only the limited number of days. I knew a distressful Irishman who entered the route with hardly any provision, broke down in the middle, and was driven along by his two carriers, who threatened his neck with their axes whenever he stopped, and only by that means succeeded in getting him through alive. Still worse was a case among my own carriers—a little boy who had been brought to carry his father’s food, as is the custom. He became crumpled up with rheumatism, and I found he had bad heart-disease as well. He kept on lying down in the path and refusing to go farther. Then he would creep away into the bush and hide himself to die. We had to track him out, and his father beat him along the march till the blood ran down his back.

But with slaves less trouble is taken. After a certain amount of beating and prodding, they are killed or left to die. Carriers are always buried by their comrades. You pass many of their graves, hung with strips of rag or decorated with a broken gourd. But slaves are never buried, and that is an evidence that the bones on the path are the bones of slaves. The Bihéans have a sentiment against burying slaves. They call it burying money. It is something like their strong objections to burying debtors. The man who buries a debtor becomes responsible for the debts; so the body is hung up on a bush outside the village, and the jackals consume it, being responsible for nothing.

Before the great change made by the “Bailundu war” of 1902, the horrors of the Hungry Country were undoubtedly worse than they are now. I have known Englishmen who passed through it four years ago and found slaves tied to the trees, with their veins cut so that they might die slowly, or laid beside the path with their hands and feet hewn off, or strung up on scaffolds with fires lighted beneath them. My carriers tell me that this last method of encouraging the others is still practised away from the pathway, but I never saw it done myself. I never saw distinct evidence of torture. The horrors of the road have certainly become less in the last three years, since the rebellion of 1902. Rebellion is always good. It always implies an unendurable wrong. It is the only shock that ever stirs the self-complacency of officials.

I have not seen torture in the Hungry Country. I have only seen murder. Every bone scattered along that terrible foot-path from Mashiko to the Cuanza is the bone of a murdered man. The man may not have been killed by violence, though in most cases the sharp-cut hole in the skull shows where the fatal stroke was given. But if he was not killed by violence, he was taken from his home and sold, either for the buyer’s use, or to sell again to a Bihéan, to a Portuguese trader, or to the agents who superintend the “contract labor” for San Thomé, and are so useful in supplying the cocoa-drinkers of England and America, as well as in enriching the plantation-owners and the government. The Portuguese and such English people as love to stand well with Portuguese authority tell us that most of the men now sold as slaves are criminals, and so it does not matter. Very well, then; let us make a lucrative clearance of our own prisons by selling the prisoners to our mill-owners as factory-hands. We might even go beyond our prisons. It is easy to prove a crime against a man when you can get £10 or £20 by selling him. And if each of us that has committed a crime may be sold, who shall escape the shackles?

The most recent case of murder that I saw was on my return through the Hungry Country, the sixth day out from Mashiko. The murdered man was lying about ten yards from the path hidden in deep grass and bracken. But for the smell I should have passed the place without noticing him as I have no doubt passed scores, and perhaps hundreds, of other skeletons that lie hidden in that forest. How long the man had been murdered I could not say, for decay in Africa varies with the weather, but the ants generally contrive that it shall be quick. I think the thing must have been done since I passed the place on my way into the country, about a month before. But possibly it was a few days earlier. My “headman” had heard of the event (a native hears everything), but it did not impress him or the other carriers in the least. It was far too common. Unhappily I do not understand enough Umbundu to make out the exact date or the details, except that the man was a slave who broke down with the usual shivering fever on the road and was killed with an axe because he could go no farther. As to the cause of death there was no doubt. When I tried to raise the head, the thick, woolly hair came off in my hand like a woven pad, leaving the skull bare, and revealing the deep gash made by the axe at the base of the skull just before it merges with the neck. As I set it down again, the skull broke off from the backbone and fell to one side. Having laid a little earth upon the body, I went on. It would take an army of sextons to bury all the poor bones which consecrate that path.

Yet, in spite of the shackles hanging on the trees, and in spite of the skeletons upon the path and the bodies of recently murdered men, I have not seen a slave caravan such as has been described to me by almost every traveller who has passed along that route into the interior. I mean, I have not seen a gang of slaves chained together, their hands shackled, and their necks held fast in forked sticks. I am not sure of the reason; there were probably many reasons combined. It is just the end of the wet season, just the time when the traders think of sending in for slaves, and not of bringing them out. Directly the natives in the Bihéan village near which I was staying heard I was going to Mashiko, though they knew nothing of my object, they said, “Now a messenger will be sent ahead to warn the slave-traders that an Englishman is coming.” The same was told me by two Englishmen who traversed the country last autumn for the mining concession, and in my case I have not the slightest doubt that messengers were sent. Again, a Portuguese trader, living on the farther side of the Hungry Country, upon the Mushi-Moshi (the Simoï, as the Portuguese classically call it), told me the drivers now bring the slaves through unknown bush-paths north of the old route. He kept a store which, being on the edge of the Hungry Country, was as frequented and lucrative as a wine-and-spirit house must be on the frontier of a prohibition State. And he was the only Portuguese I have met who recognized the natives as fellow-subjects, and even as fellow-men, with rights of their own. He also boasted, I think justly, of the good effects of the war in 1902.

All these reasons may have contributed. But still I think that the old caravan system has been reduced within the last three years. The shock to public feeling in Portugal owing to the Bailundu war and its revelations; the disgrace of certain officers at the forts, who were convicted of taking a percentage of slaves from the passing caravans as hush-money; the strong action of Captain Amorim in trying to suppress the whole traffic; the instructions to the forts to allow no chained gangs to pass—all these things have, I believe, acted as a check upon the old-fashioned methods. There is also an increased risk in obtaining slaves from the interior in large batches. The Belgians strongly oppose the entrance of the traders into their state, partly because guns and powder are the usual exchange for slaves, partly because they wish to retain their own natives under their own tender mercies. The line of Belgian forts along the frontier is quickly increasing. Some Bihéan traders have been shot. In one recent case, much talked of, a bullet from a Maxim gun struck the head of a gang of slaves, marching as usual in single file, and killed nine in succession. In any case, the traders seem to have discovered that the palmy days when they used to parade their chained gangs through the country, and burn, flog, torture, and cut throats as they pleased, are over for the present. For many months after the war even the traffic to San Thomé almost ceased. It has begun again now and is rapidly increasing. As I noted in a former letter, an order was issued in December, 1904, requiring the government agents to press on the supply. But at present, I think, the slaves are coming down in smaller gangs. They are not, as a rule, tortured; they are shackled only at night, and the traders take a certain amount of pains to conceal the whole traffic, or at least to make it look respectable.

As to secrecy, they are not entirely successful. A man whose word no one in Central Africa would think of doubting has just sent down notice from the interior that a gang of two hundred and fifty slaves passed through the Nanakandundu district, bound for the coast, in the end of February (1905), shackles and all. The man who brought the message had done his best to avoid the gang, fearing for his life. But there is no doubt they are coming through, and I ought to have met them near Mashiko if they had not taken a by-path or been broken up into small groups.

It was probably such a small group that I met within a day’s journey of Caiala, the largest trading-house in Bihé. I was walking at about half an hour’s distance from the road, when suddenly I came upon a party of eighteen or twenty boys and four men hidden in the bush. At sight of me they all ran away, the men driving the boys before them. But they left two long chicotes or sjamboks (hide whips) hanging on the trees, as well as the very few light loads they had with them. After a time I returned, and they ran away again. I then noticed that they posted a man on a tree-top to observe my movements, and he remained there till I trekked on with my own people. Of course the evidence is not conclusive, but it is suspicious. Men armed with chicotes do not hide a group of boys in the bush for nothing, and it is most probable that they formed part of a gang going into Bihé for sale.

I may have passed many such groups on my journey without knowing it, for it is a common trick of the traders now to get up the slaves as ordinary carriers. But among all of them, there was only one which was obviously a slave gang, almost without concealment. My carriers detected them at once, and I heard the word “apeka” (slaves)[3] passed down the line even before I came in sight of them. The caravan numbered seventy-eight in all. In front and rear were four men with guns, and there were six of them in the centre. The whole caravan was organized with a precision that one never finds among free carriers, and nearly the whole of it consisted of boys under fourteen. This in itself would be almost conclusive, for no trade caravan would contain anything like that proportion of boys, whereas boys are the most easily stolen from native villages in the interior, and, on the whole, they pay the cost of transport best. But more conclusive even than the appearance of the gang was the quiet evidence of my own carriers, who had no reason for lying, who never pointed out another caravan of slaves, and yet had not a moment’s doubt as to this.

The importation of slaves from the interior into Angola may not be what it was. It may not be conducted under the old methods. There is no longer that almost continuous procession of chained and tortured men and women which all travellers who crossed the Hungry Country before 1902 describe. For the moment rubber has become almost as lucrative as man. The traffic has been driven underground. There is now a feeling of shame and risk about it, and the military authorities dare not openly give it countenance as before. But I have never heard of any case in which they openly interfered to stop it, and the thing still goes on. It is, in fact, fast recovering from the shock of the rebellion of 1902, and is now increasing again every month.

It will go on and it will increase as long as the authorities and traders habitually speak of the natives as “dogs,” and allow the men under their command to misuse them at pleasure. To-day a negro soldier in the white Portuguese uniform seized a little boy at the head of my carriers, pounded his naked feet with the butt of his rifle, and was beating him unmercifully with the barrel, when I sprang upon him with two javelins which I happened to be carrying because my rifle was jammed. At sight of me the emblem of Portuguese justice crawled on the earth and swore he did not know it was a white man’s caravan. That was sufficient excuse.

Three days ago word came to me on the march that one of my carriers had been shot at and wounded. We were in a district where three Chibokwe natives actually with shields and bows as well as guns had hung upon our line as we went in. I had that morning warned the carriers for the twentieth time that they must keep together, and had set an advanced and rear guard, knowing that stray carriers were being shot down. But natives are as incapable of organization as of seeing a straight line, and my people were straggled out helplessly over a length of five or six miles. Hurrying forward, I found that the bullet—a cube of copper—had just missed my carrier’s head, had taken a chip out of his hand, and gone through my box. The carrier behind had caught the would-be murderer, and there he stood—a big Luvale man, with filed teeth, and head shaved but for a little tuft or pad at the top. I supposed he ought to be shot, but my rifle was jammed, and I am not a born executioner. However, I cleared a half-circle and set the man in the middle. A great terror came into his face as I went through the loading motions. I had determined, having blindfolded him, to catch him a full drive between the eyes. This would give him as great a shock as death. He would think it was death, and yet would have time to realize the horror of it afterwards, which in the case of death he would not have. But when all was ready, my carriers, including the wounded man, set up a great disturbance, and seized the muzzle of my rifle and turned it aside. They kept shouting some reason which I did not then understand. So I gave the punishment over to them, and they took the man’s gun—a trade-gun or “Lazarino,” studded with brass nails—stripped him of his powder-gourd, cloth, and all he had, beat him with the backs of their axes, and drove him naked into the forest, where he disappeared like a deer.

I found out afterwards that their reason for clemency was the fear of Portuguese vengeance upon their villages, because the man was employed by the fort at Mashiko, and therefore claimed the right of shooting any other native at sight, even over a minute’s dispute about yielding the foot-path.

Such small incidents are merely typical of the attitude which the Portuguese take towards the natives and allow their own black soldiers and slaves to take. As long as this attitude is maintained, the immensely profitable slave-traffic which has filled with its horrors this route for centuries past will continue to fill it with horrors, no matter how secret or how legalized the traffic may become.

I have pitched my tent to-night on a hill-side not far from the fort of Matota, where a black sergeant and a few men are posted to police the middle of the Hungry Country. In front of me a deep stream is flowing down to the Zambesi with strong but silent current in the middle of a marsh. The air is full of the cricket’s call and the other quiet sounds of night. Now and then a dove wakes to the brilliant moonlight, and coos, and sleeps again. Sometimes an owl cries, but no leopards are abroad, and it would be hard to imagine a scene of greater peace or of more profound solitude. And yet, along this path, there is no solitude, for the dead are here; neither is there any peace, but a cry.