VII

SAVAGES AND MISSIONS

The Chibokwe do not sell their slaves; they kill them; and this distinction between them and the Bihéans is characteristic. The Bihéans are carriers and traders. They always have an eye fixed on the margin of profit. They will sell anything, including their own children, and it is waste to kill a man who may be sold to advantage. But the Chibokwe are savages of a wilder race, and no Bihéan would dare buy a Chibokwe slave, even if they had the chance. They know that the next Bihéan caravan would be cut to pieces on its way.

It is impossible to fix the limits of the Chibokwe country. The people are always on the move. It is partly the poverty of the land that drives them about, partly their habit of burning the village whenever the chief dies; and as villages go by the chief’s name, they are the despair of geographers. But in entering the interior you may begin to be on your guard against the Chibokwe two days after crossing the Cuanza. They have a way of cutting off stray carriers, and, as I mentioned in my last letter, my own little caravan was dogged by three of them with shields and spears, who might have been troublesome had they known that the Winchester with which I covered the rear was only useful as a club. It was in the Chibokwe country, too, that the one attempt was made to rob my tent at night, and again I only beat off the thieves by making a great display with a jammed rifle. On one side their villages are mixed up with the Luimbi, on the other with the Luena people and the Luvale, who are scattered over the great, wet flats between Mashiko and Nanakandundu. But they are a distinct people in themselves, and they appear to be increasing and slowly spreading south. If the King of Italy’s arbitration gives the Zambesi tributaries to England, the Chibokwe will form the chief part of our new fellow-subjects, and will share the legal advantages of Whitehall.[4]

They file or break their teeth into sharp points, whereas the Bihéans compromise by only making a blunt angle between the two in front. It used to be said that pointed teeth were the mark of cannibalism, but I think it more likely that these tribes at one time had the crocodile or some sharp-toothed fish as their totem, and certainly when they laugh their resemblance to pikes, sharks, or crocodiles is very remarkable. Anyhow, the Chibokwe are not cannibals now, except for medicine, or in the hope of acquiring the moral qualities of the deceased. But I believe they eat the bodies of people killed by lightning or other sudden death, and the Bihéans do the same.

Though not so desert as the Hungry Country, the soil of their whole district is poor, and the people live in great simplicity. Hardly any maize is grown, and the chief food is the black bean, a meal pounded from yellow millet, and a beetle about four inches long. In all villages there are professional hunters and fishers, but game is scarce, and the fish in such rivers as the Mushi-Moshi (Simoï) are not allowed to grow much above the size of whitebait. Honey is to be found in plenty, but for salt, which is their chief desire, they have to put up with the ashes of a burned grass, unless they can buy real salt from the Bihéans in exchange for millet or rubber. Just at present rubber is their wealth, and they are doing rather a large trade in it. All over the forests they are grubbing up the plant by the roots, and in the villages you may hear the women pounding and tearing at it all the afternoon. But rubber thus extirpated gives a brief prosperity, and in two years, or five at the most, the rubber will be exhausted and the Chibokwe thrown back on their natural poverty.

In the arts they far surpass all their neighbors on the west side. They are so artistic that the women wear little else but ornament. Their houses are square or oblong, with clean angles and straight sides, and the roofs, instead of being conical, are oblong too, having a straight beam along the top, like an English cottage. The tribe is specially famous for its javelins, spears, knives, hatchets, and other iron-work, which they forge in the open spaces round the village club-house, working up their little furnaces with wooden tubes and bellows of goat-skin, like loose drum-heads, pulled up and down with bits of stick to make a draught. A simple pattern is hammered on some of the axes, and on the side of one hut I saw an attempt at fresco—a white figure on a red ground under a white moon—the figure being quite sufficiently like an ox.

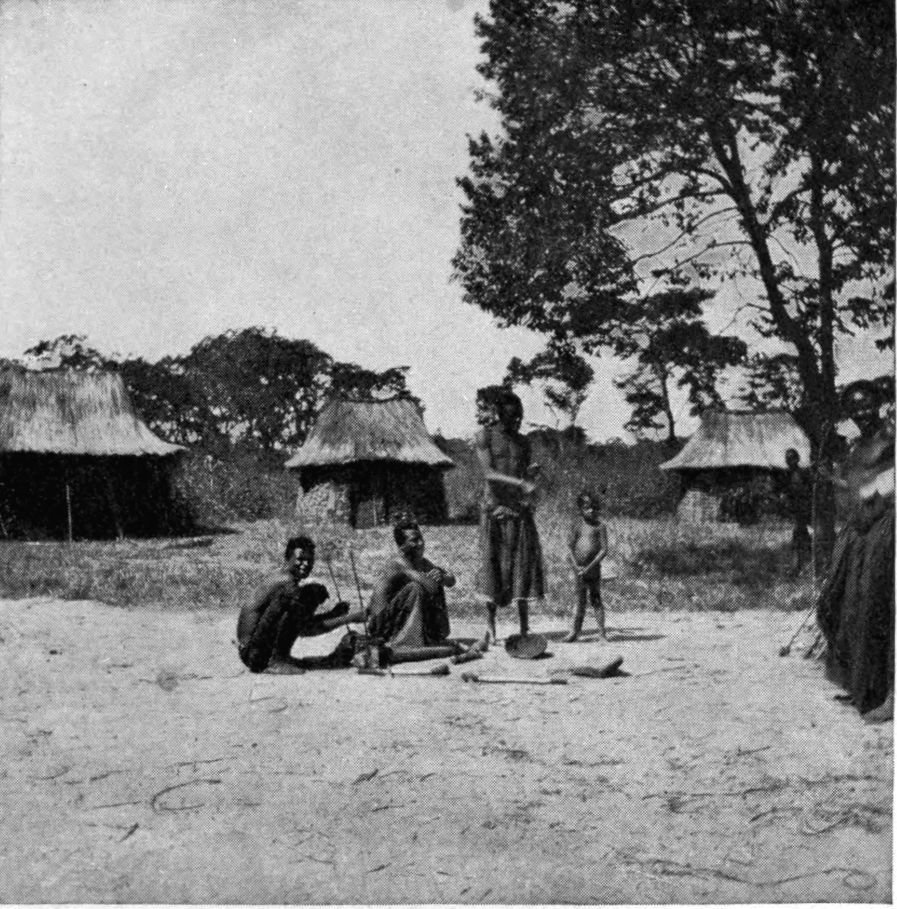

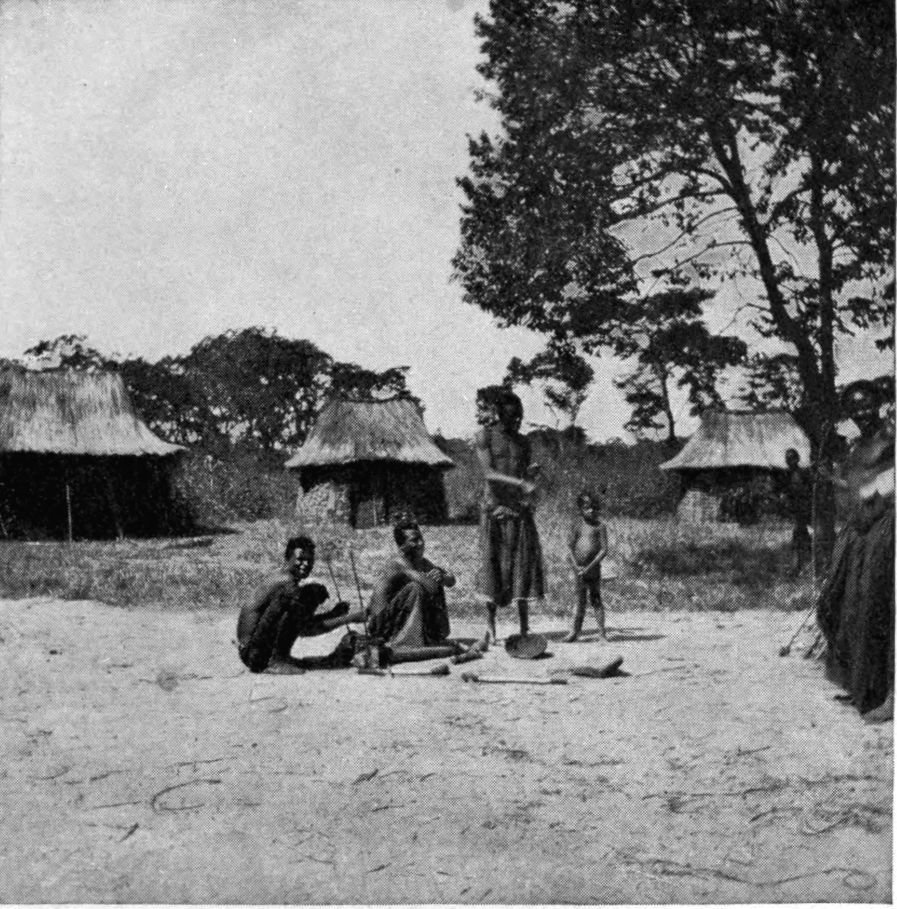

A CHIBOKWE FORGE WHERE NATIVE SPEARS ARE MADE

In dancing, the Chibokwe excel, like the Luvale people, who are their neighbors on the eastern side, farther in the interior, and their dances are much the same. It is curious that their favorite form is almost exactly like the well-known Albanian dance of the Greeks. Standing in a broken circle, they move round and round to a repeated song, while the leader sets the pace, and now and again springs out into the centre to display his steps. The Chibokwe introduce a few varieties, the man in the centre beckoning with his hand to any one in the ring to perform the next solo, and he in turn calling on another. There is also much more movement of the body than in the Albanian dance, the chief object of the art being to work the shoulders up and down, and wriggle the backbone as much like a snake as possible. But the general idea of the dance is the same, and neither the movement nor the singing nor the beat of the drum alters much throughout a moonlit night.

It is natural that the Chibokwe should have retained much of the religious feeling and rites which the commercial spirit has destroyed in the Bihéans. They are far more alive to the spiritual side of nature, and the fetich shrines are more frequent in all their villages. The gate of every village, and, indeed, of almost every house, has its little cluster of sticks, with antelope skulls stuck on the tops, or old rags fluttering, or a tiny thatched roof covering a patch of strewn meal. The people have a way of painting the sticks in red and black stripes, and so the fisher paints the rough model of a canoe that he hangs by his door to please the fishing spirit. Or sometimes he hangs a little net, and the hunter, besides his cluster of horned skulls, almost always hangs up a miniature turtle three or four inches long. I cannot say for what reason, but all these charms are not to avert evil so much as to win the favor of a benign spirit who loves to fish or hunt. So far the rites are above the usual African religion of terror or devil-worship. But when a woman with child carves a wooden bird to hang over her door, and gives it meal every evening and sprinkles meal in front of her door, I think her object is to ward off the spirits of evil from herself and her unborn baby.

In a Chibokwe village, one burning afternoon, I found a native woman being treated for sickness in the usual way. She was stretched on her back in the dust and dirt of the public place, where she had lain for four days. The sun beat upon her; the flies were thick upon her body. Over her bent the village doctor, assiduous in his care. He knew, of course, that the girl was suffering from witchcraft. Some enemy had put an evil spirit upon her, for in Africa natural death is unknown, and but for witchcraft and spirits man would be immortal. But still the doctor was trying the best human means he knew of as well. He had plastered the girl’s body over with a compound of leaves, which he had first chewed into a pulp. He had then painted her forehead with red ochre, and was now spitting some white preparation of meal into her nose and mouth. The girl was in high fever—some sort of bilious fever. You could watch the beating of her heart. The half-closed eyes showed deep yellow, and the skin was yellow too. Evidently she was suffering the greatest misery, and would probably die next day.

It happened that two Americans were with me, for I had just reached the pioneer mission station at Chinjamba, beyond Mashiko. One of them was a doctor, with ten years’ experience in a great American city, and after commending the exertions of the native physician, he asked to be allowed to assist in the case himself. The native agreed at once, for the white man’s fame as an exorcist had spread far through the country. Four or five days later I saw the same girl, no longer stretched on hot dust, no longer smeared with spittle, leaves, and paint, but smiling cheerfully at me as she pounded her meal among the other women.

The incident was typical of those two missionaries and their way of associating with the natives. It is typical of most young missionaries now. They no longer go about denouncing “idols” and threatening hell. They recognize that native worship is also a form of symbolism—a phase in the course of human ideas upon spiritual things. They do not condemn, but they say, “We think we know of better things than these,” and the native is always willing to listen. In this case, for instance, after the girl had been put into a shady hut and doctored, the two missionaries sat down on six-inch native stools outside the club-house and began to sing. They were pioneers; they had only three hymns in the Chibokwe language, and they themselves understood hardly half the words. No matter; they took the meaning on trust. By continued repetition, by feeling no shame in singing a hymn twenty or thirty times over at one sitting, they had got the words fixed in the native minds, and when it came to the chorus the whole village shouted together like black stars. The missionaries understood the doctrine, the people understood the words; it was not a bad combination, and I thought those swinging choruses would never stop. The preaching was perhaps less exhilarating to the audience, but so it has sometimes been to other congregations, and the preacher’s knowledge of the language he spoke was only five months old.

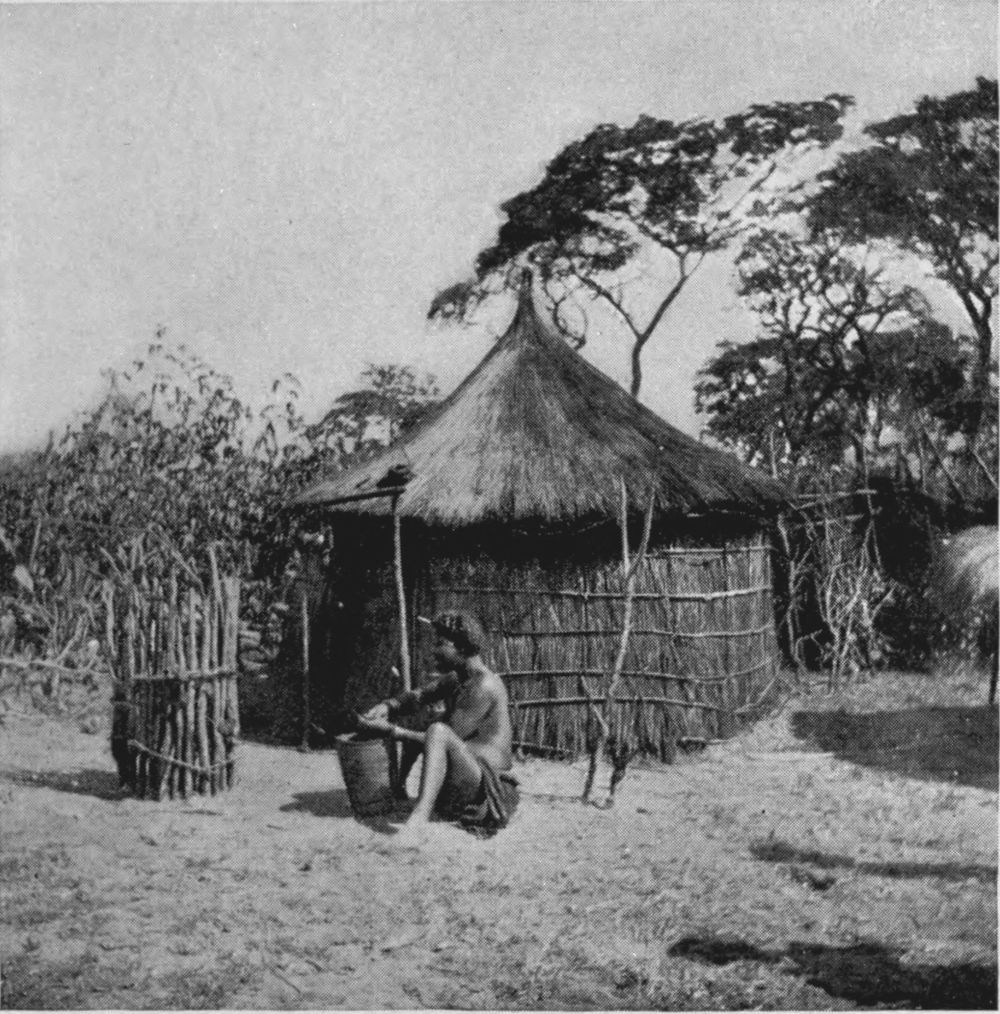

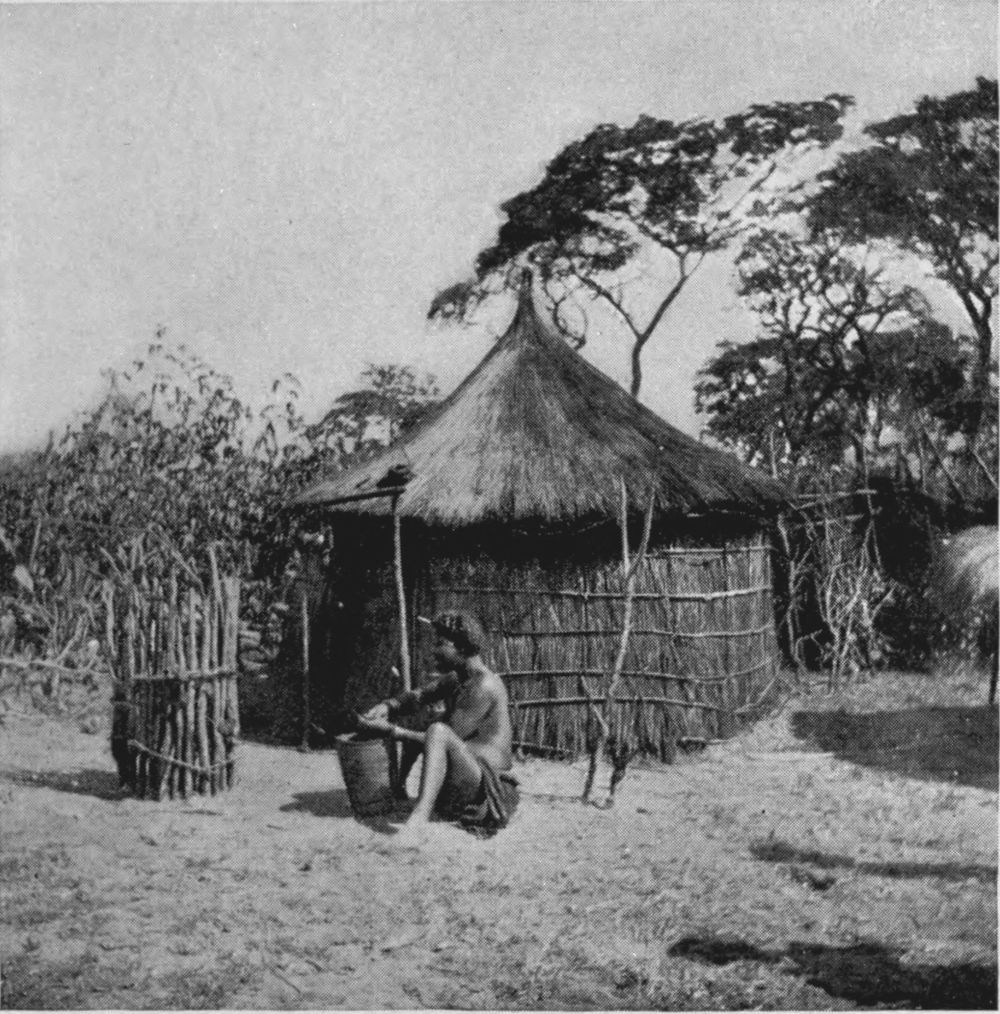

A CHIBOKWE WOMAN AND HER FETICHES

At the mission it was the same thing. The pioneers had set up a log hut in the forest, admitting the air freely through the floor and sides. They were living in hard poverty, but when they shared with me their beans and unleavened slabs of millet, it was pleasant to know that each of the two doors on either side of the hut was crammed with savage faces, eagerly watching the antics of civilization at meals. One felt like a lantern-slide, combining instruction with amusement. The audience consisted chiefly of patients who had built a camp of forty or fifty huts close outside the cabin, and came every morning to be cured—cured of broken limbs, bad insides, wounds, but especially of the terrible sores and ulcers which rot the shins and thighs, tormenting all this part of Africa. Among the patients were three kings, who had come far from the east. The greatest of them had brought a few wives—eight, I think—and some children, including a singularly fascinating princess with the largest smile I ever saw. Every morning the king came to my tent, showed me his goitre, asked for tobacco, and sat with me an hour in silent esteem. As I was not then accustomed to royalty, I was uncertain how three kings would behave themselves in hospital life; but in spite of their rank and station, they were quite good, and even smiled upon the religious services, feeling, no doubt, as all the rich feel, that such things were beneficial for the lower orders.

On certain evenings the missionaries went out into the hospital camp to sing and pray. They sat beside a log fire, which threw its light upon the black or copper figures crowding round in a thick half-circle—big, bony men, women shining with castor-oil, and swarms of children, hardly visible but for a sudden gleam of eyes and teeth. The three invariable hymns were duly sung—the chorus of the favorite being repeated seventeen times without a pause, as I once counted, and even then the people showed no sign of weariness. The woman next to me on that occasion sang with conspicuous enthusiasm. She was young and beautiful. Her mop of hair, its tufts solid with red mud, hung over her brow and round her neck, dripping odors, dripping oil. Her bare, brown arms jingled with copper bracelets, and at her throat she wore the section of round white shell which is counted the most precious ornament of all—“worth an ox,” they say. Her little cloth was dark blue with a white pattern, and, squatted upon her heels, she held her baby between her thighs, stuffing a long, pointed breast into his mouth whenever he threatened to interrupt the music. For her whole soul was given to the singing, and with wide-open mouth she poured out to the stars and darkened forests the amazing words of the chorus:

“Haleluyah! mwa aku kula,

Jesu vene mwa aku sanga:”

There were two other lines, which I do not remember. The first line no one could interpret to me. The second means, “Jesus really loves me.” The other two said, “His blood will wash my black heart white.”

To people brought up from childhood in close familiarity with words like these there may be nothing astonishing about them. They have unhappily become the commonplaces of Christianity, and excite no more wonder than the sunrise. But I would give a library of theology to know what kind of meaning that brown Chibokwe woman found in them as she sat beside the camp-fire in the forest beyond the Hungry Country, and sang them seventeen times over to her baby and the stars.

When at last the singing stopped, one of the missionaries began to read. He chose the first chapter of St. John, and in that savage tongue we listened to the familiar sentences, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Again I looked round upon that firelit group of naked barbarians. I remembered the controversies of ages, the thinkers in Greek, the seraphic doctors, the Byzantine councillors, the saints and sinners of the intellect, Augustine in the growing Church, Faust in his study—all the great and subtle spirits who had broken their thought in vain upon that first chapter of St. John, and again I was filled with wonder. “For Heaven’s sake, stop!” I felt inclined to cry. “What are these people to understand by ‘the beginning’? What are we to understand by ‘the Word’?” But when I looked again I recognized on all faces the mood of stolid acquiescence with which congregations at home allow the same words to pass over their heads year after year till they die as good Christians. So that I supposed it did not matter.

There seems to be a fascination to missionaries in St. John’s Gospel, and, of course, that is no wonder. It is generally the first and sometimes the only part of the New Testament translated, and I have seen an old chief, who was diligently learning to read among a class of boys, spelling out with his black fingers such words as, “I am in the Father, and the Father in me.” No doubt it may be said that religion has no necessary connection with the understanding, but I have sometimes thought it might be better to begin with something more comprehensible, both to savages and ourselves.

On points of this kind, of course, the missionaries may very well be right, but in one thing they are wrong. Most of them still keep up the old habit of teaching the early parts of the Old Testament as literal facts of history. But if there is anything certain in human knowledge, the Old Testament stories have no connection with the facts of history at all. No one believes they have. No scholar, no man of science, no theologian, no sane man would now think of accepting the Book of Genesis as a literal account of what actually happened when the world and mankind began to exist. Yet the missionaries continue to teach it all to the natives as a series of facts. I have heard one of the most experienced and influential of all the missionaries discussing with his highest class of native teachers whether all Persons of the Trinity were present at Eve’s temptation; and when one of them asked what would have happened if Adam had refused to eat the apple, the class was driven to suppose that in that case men would have remained perfect, while women became as wicked as we see them now. It was a doctrine very acceptable to the native mind, but to hear those rather beautiful old stories still taught as the actual history of the world makes one’s brain whirl. One feels helpless and confused and adrift from reason, as when another missionary, whose name is justly famous, told me that there were references to Moscow in Ezekiel, and Daniel had exactly foretold the course of the Russo-Japanese war. The native has enough to puzzle his brain as it is. On one side he has the Christian ideal of peace and good-will, of temperance and poverty and honor and self-sacrifice, and of a God who is love. And on the other side he has somehow to understand the Christian’s contumely, the Christian’s incalculable injustice, his cruelty and deceit, his insatiable greed for money, his traffic in human beings whom the Christian calls God’s children. When the native’s mind is hampered and entangled in questions like these, no one has a right to increase his difficulties by telling him to believe primitive stories which, as historical facts, are no truer than the native’s own myths.

But, happily, matters of intellectual belief have very little to do with personality, and many good men have held unscientific views on Noah’s Ark. Contrary to nearly all travellers and traders in Africa, I have nothing but good to say of the missionaries and their work. I have already mentioned the order of the Holy Spirit and their great mission at Caconda. The same order has two other stations in South Angola and a smaller station among the mountains of Bailundu, about two hours distant from the fort and the American mission there. Its work is marked by the same dignity and quiet devotion as marks the work of all the orders wherever I have come across their outposts and places of danger through the world. It is constantly objected that the Portuguese have possessed this country for over four centuries, and have done nothing for the improvement or conversion of the natives, and I bear in mind those bishops of Loanda who sat on marble thrones upon the quay christening the slaves in batches as they were packed off by thousands to their misery in Cuba and Brazil. Both things are perfectly true. The Portuguese are not a missionary people. I have not met any but French, Alsatians, and Germans in the missions of the order out here. But that need not in the least diminish our admiration of the missions as they now are. Nor should we be too careful to remember the errors and cruelties of any people or Church in the past, especially when we reflect that England, which till quite lately was regarded as the great foe of slavery all over the world, was also the originator of the slave export, and that the supreme head of the Anglican Church was one of the greatest slave-traders ever known.

As to the scandals and sneers of traders, officials, and gold-prospectors against the missions, let us pass them by. They are only the weary old language of “the world.” They are like the sneers of butchers and publicans at astronomy. They are the tribute of the enemy, the assurance that all is not in vain. It would be unreasonable to expect anything else, and dangerous to receive it. The only thing that makes me hesitate about the work of the order is that many traders and officials have said to me, “The Catholic missions are, at all events, practical; they do teach the natives carpentering and wagon-building and how to dig.” It is perfectly true and admirable, and, as a matter of fact, the other missions do the same. But a mission might teach its followers to make wagons enough for a Boer’s paradise and doors enough for all the huts in Africa and still have failed of its purpose.

Besides the order of the Holy Spirit, there are two other notable orders at work in Angola—the American mission (Congregationalist) under the “American Board,” and the English mission (Plymouth Brethren) under divine direction only. Each mission has four stations, and each is about to start a new one. Some members of the English mission are Americans, like the pioneers at Chinjamba, and all are on terms of singular friendship, helping one another in every possible way, almost like the followers of Christ. Of all sects that I have ever known, these are the only two that I have heard pray for each other, and that without condemnation—I mean they pray in a different spirit from the Anglican prayer for Jews, Turks, infidels, and heretics. There is another American order, called the Wesleyan Episcopalian, with stations at Loanda and among the grotesque mountains of Pungo Ndongo. English-speaking missionaries have now been at work in Loanda for nearly twenty-five years, and some of the pioneers, such as Mr. Arnot, Mr. Currie, Mr. Stover, Mr. Fay, and Mr. Sanders, are still directing the endeavor, with a fine stock of experience to guide them. They have outlived much abuse; they have almost outlived the common charge of political aims and the incitement of natives to rebellion, as in 1902. The government now generally leaves them alone. The Portuguese rob them, especially on the steamers and in the customs, but then the Portuguese rob everybody. Lately the American mission village at Kamundongo in Bihé has been set on fire at night three or four times, and about half of it burned down. But this appears to be the work of one particular Portuguese trader, who has a spite against the mission and sends his slaves from time to time to destroy it. An appeal to the neighboring fort at Belmonte would, of course, be useless. If the Chefe were to see justice done, the neighboring Portuguese traders would at once lodge a complaint at Benguela or Loanda, and he would be removed, as all Chefes are removed who are convicted of justice. But, as a rule, the missions are now left very much to themselves by the Portuguese, partly because the traders have found out that some of the missionaries—four at least—are by far the cleverest doctors in the country, and nobody devotes his time to persecuting his doctor.

As to the natives, it is much harder to judge their attitude. Their name for a missionary is “afoola,” and though, I believe, the word only means a man of learning, it naturally suggests an innocent simplicity—something “a bit soft,” as we say. At first that probably was the general idea, as was seen when M. Coillard, the great French missionary of Barotzeland, had a big wash in his yard one afternoon, and next Sunday preached to an enthusiastic congregation all dressed in scraps of his own linen. And to some extent the feeling still exists. There are natives who go to a mission village for what they can get, or simply for a sheltered existence and kindly treatment. There are probably a good many who experience religious convictions in order to please, like the followers of any popular preacher at home. But, as a rule, it is not comfort or gain, it is not persuasive eloquence or religious conviction that draws the native. It is the two charms of entire honesty and of inward peace. In a country where the natives are habitually regarded as fair game for every kind of swindle and deceit, where bargains with them are not binding, and where penalties are multiplied over and over again by legal or illegal trickery, we cannot overestimate the influence of men who do what they say, who pay what they agree, and who never go back on their word. From end to end of Africa common honesty is so rare that it gives its possessor a distinction beyond intellect, and far beyond gold. In Africa any honest man wins a conspicuous and isolated greatness. In twenty-five years the natives of Angola have learned that the honesty of the missionaries is above suspicion. It is a great achievement. It is worth all the teaching of the alphabet, addition, and Old Testament history, no matter how successful, and it is hardly necessary to search out any other cause for the influence which the missionaries possess.

So, as usual, it is the unconscious action that is the best. Being naturally and unconsciously honest, the missionaries have won the natives by honesty—have won, that is to say, the almost imperceptible percentage of natives who happen to live in the three or four villages near their stations; and it must be remembered that you might go through Angola from end to end without guessing that missionaries exist. But, apart from this unconscious influence, there are plenty of conscious efforts too. There is the kindergarten, where children puddle in clay and sing to movement and march to the tune of “John Brown.” There are schools for every stage, and you may see the chief of a village doing sums among the boys, and proudly declaring that for his part 3 + 0 + 1 shall equal five.[5] There are carpenters’ shops and forges and brick-kilns and building classes and sewing classes for men. There are Bible classes and prayer-meetings and church services where six hundred people will be jammed into the room for four hundred, and men sweat, and children reprove one another’s behavior, and babies yell and splutter and suck, and when service is over the congregation rush with their hymn-books to smack the mosquitoes on the walls and see the blood spurt out. There are singing classes where hymns are taught, and though the natives have nothing of their own that can be called a tune, there is something horrible in the ease with which they pick up the commonplace and inevitable English cadences. I once had a set of carriers containing two or three mission boys, and after the first day the whole lot “went Fantee” on “Home, Sweet Home,” just a little wrong. For more than two years I have journeyed over Africa in peace and war, but I have never suffered anything to compare to that fortnight of “Home, Sweet Home,” just a little wrong, morning, noon, and night.

All these methods of instruction and guidance are pursued in the permanent mission stations, to say nothing of the daily medical service of healing and surgery, which spreads the fame of the missions from village to village. Many out-stations, conducted by the natives themselves, have been formed, and they should be quickly increased, though it is naturally tempting to keep the sheep safe within the mission fold. If the missionaries were suddenly removed in a body, it is hard to say how long their teaching or influence would survive. My own opinion is that every trace of it would be gone in fifty or perhaps in twenty years. The Catholic forms would probably last longest, because greater use is made of a beautiful symbolism. But in half a century rum, slavery, and the oppression of the traders would have wiped all out, and the natives would sink into a far worse state than their original savagery. Whether the memory of the missions would last even fifty years would depend entirely upon the strength and number of the out-stations.

In practical life, the three great difficulties which the missions have to face are rum, polygamy, and slavery. From their own stations rum can be generally excluded, though sometimes a village is persecuted by a Portuguese trader because it will not buy his spirit. But the whole country is fast degenerating owing to rum. “You see no fine old men now,” is a constant saying. Rum kills them off. It is making the whole people bloated and stupid. Near the coast it is worst, but the enormous amount carried into the interior or manufactured in Bihé is telling rapidly, and I see no hope of any change as long as rum plantations of cane or sweet-potato pay better than any others, and both traders and government regard the natives only as profitable swine.

As a matter of argument, polygamy is a more difficult question still. It is universally practiced in Africa, and no native man or woman has ever had the smallest scruple of conscience or feeling of wrong about it. Where the natives can observe white men, they see that polygamy is in reality practiced among them too. If they came to Europe or America, they would find it practiced, not by every person, but by every nation under one guise or another. It seems an open question whether the native custom, with its freedom from concealment and its guarantees for woman’s protection and support, is not better than the secret and hypocritical devices of civilization, under which only one of the women concerned has any protection or guarantee at all, while a man’s relation to the others is nearly always stealthy, cruel, and casual. However, the missionaries, after long consideration, have decided to insist upon the rule of one man one wife for members of their Churches, and when I was at one station a famous Christian chief, Kanjumdu of Chiuka—by far the most advanced and intelligent native I have ever known—chose one wife out of his eight or ten, and married her with Christian rites, while the greater part of his twenty-four living children joined in the hymns. It was fine, but my sympathy was with one of the rejected wives, who would not come to the wedding-feast and refused to take a grain of meal or a foot of cloth from his hand ever again.

As to slavery, I have already spoken about the missionaries’ attitude. They dare not say anything openly against it, because if they published the truth they would probably be poisoned and certainly be driven out of the country, leaving their followers exposed to a terrible and exterminating persecution. So they help in what few special cases they can, and leave the rest to time and others. It is difficult to criticize men of such experience, devotion, and singleness of aim. One must take their judgment. But at the same time one cannot help remembering that a raging fire is often easier to deal with than a smouldering refuse-heap, and that in spite of all the blood and sorrow, the wildest revolution on behalf of justice has never really failed.

But, as I said, it is hard for me to criticize the missionaries out here. My opinion of them may be misguided by the extraordinary kindliness which only traders and officials can safely resist, and I suppose one ought to envy the reasonableness of such people when, after enjoying the full hospitality of the mission stations, they spend the rest of their time in sneering at the missionaries. Nothing can surpass mission hospitality. The stranger’s condition, poverty, or raggedness does not matter in the least, nor does the mission’s own scarcity or want. Whatever there is belongs to the strangers, even if nothing is left but a dish of black beans and a few tea-leaves, used already. In a long and wandering life I have nowhere found hospitality so complete and ungrudging and unconscious. Only those who have lived for months among the dirt and cursing of ox-wagons, or have tramped with savages far through deserts wet and dry, plunged in slime or burned with thirst, worn with fever and poisoned with starvation, could appreciate what it means to come at last into a mission station and see the trim thatched cottages, like an old English village, and to hear the quiet and pleasant voices, and feel again the sense of inward peace, which, I suppose, is the reward of holy living. How often when I have been getting into bed the night after I have thus arrived, I have thought to myself, “Here I am, free from hunger and thirst, in a silent room, with a bed and real sheets, while people at home probably picture me dying in the depths of a dismal forest where pygmies sharpen their poisoned arrows and make their saucepans ready, or a lion stands rampant on one side of me, and, on the other side, a unicorn.”