VIII

THE SLAVE ROUTE TO THE COAST

After coming out from the interior by passing again through the Hungry Country from the Zambesi basin to the Cuanza, I determined to continue following the old slave route down to Benguela and the sea. I have already spoken of this route as the main road of Central Africa, and the two hundred and seventy or three hundred miles of it which connect Bihé with the coast are crowded with trade, especially at the beginning of the dry season, which was the time of my journey. It is only a carrier’s track, though the Portuguese, as their habit is, have forced the natives to construct a few miles of useless road here and there, at intervals of several days’ march. But along that winding track, sometimes so steep and difficult that it is like a goat-path in the Alps, thousands of carriers pass every year, bearing down loads of rubber and beeswax, and bringing back cotton, salt, tinned foods, and, above all, rum. It is against the decree of the Brussels Conference of 1890 to introduce rum into Bihé at all, but who cares about decrees when rum pays and no one takes the trouble to shoot? And down this winding track the export slaves have been driven century after century. I suppose the ancestors of half the negroes in the United States and of nearly all in Cuba and Brazil came down it. And thousands of export slaves still come down it every year. Laws and conferences have prohibited the slave-trade for generations past, but who cares about laws and conferences as long as slavery pays and no one takes the trouble to shoot?

How the traffic is worked may be seen from some things which I observed upon my way. Being obliged to wait at various places to arrange carriers and recover from fevers, I spent about five weeks on the road from the crossing of the Cuanza to the sea, though it can be done in three weeks, or even in seventeen days. For the first few days I was back again in the northern part of the Bihé district, and I early passed the house of a Portuguese trader of whose reputation I had heard before. He is still claiming enormous damages for injury to his property in the war of 1902. The villagers have appealed to the fort at Belmonte against the amount, but are ordered to pay whatever he asks. To supply the necessary rubber and oxen they have now pawned their children into slavery without hope of redemption. Two days before I passed the house a villager, having pawned the last of his children and possessing nothing else, had shot himself in the bush close by. Things like that make no difference to the trader. It is the money he wants. The damage done to his property three years ago must be paid for twentyfold. Still, he is not simply the “economic man” of the old text-books. He has a decadent love of art, distinct from love of money, and just before I passed his house he had summoned the chiefs of the village as though for a conference, had locked them up in his compound, and every night he was making the old men dance for his pleasure. To the native mind such a thing is as shocking as it would be to Englishmen if Mr. Beit or Mr. Eckstein kept the Lord Chancellor and the Archbishop of Canterbury to gambol naked before him on Sunday afternoons.

ON THE WAY TO THE COAST

So the matter stands, and the villagers must go on selling more and more of their wives and children that the white man’s greed may be satisfied.

A day or two farther on I turned aside from the main track to visit one of the agents whom the government has specially appointed to conduct the purchase of slaves for the islands of San Thomé and Principe. There are two agents officially recognized in the Bihé district. On my way I met an old native notorious for a prosperous career of slave-trading. At the moment he was leading along a finely built man by a halter round his neck, but at sight of me he dropped the end of rope. A man who was with me charged him at once with having just sold two of his own slaves—a man and a woman—for San Thomé. He protested with righteous indignation. He would never think of doing such a thing! Sell for San Thomé! He would even give a long piece of cloth to rescue a native from such a fate! Yet, beyond question, he had sold the man and woman to the Agent that morning. They were at the Agent’s house when I arrived, and I was told he had only failed to sell the other slave because his price was too high.

The Agent himself was polite and hospitable. Business was pretty brisk. I knew he had sent off eight slaves to the coast only three days before, with orders that they should carry their own shackles and be carefully pinned together at night. But we talked only of the rumored division of the Congo, for on the other subject he was naturally a little shy, and I found out long afterwards that he knew the main object of my journey.[6] Next day, however, he was alone with the friend who had accompanied me, and he then attempted to defend his position as Agent by saying the object of the government was to buy up slaves through their special agents and “redeem” them from slavery by converting them into “contract laborers” for San Thomé. The argument was ingenious. The picture of a pitiful government willing to purchase the freedom of all slaves without thought of profit, and only driven to contract them for San Thomé because otherwise the expense would be unbearable—it is almost pathetic. But the Agent knew, as every one out here knows, that the people whom the government buys and “redeems” have been torn from their homes and families on purpose to be “redeemed”; that but for the purchases by the government agents for San Thomé the whole slave-traffic would fall to pieces; and that the actual condition of these “contracted laborers” upon the islands does not differ from slavery in any point of importance.

Leaving on the right the volcanic district of North Bihé, with its boiling springs and great deposits of magnesia, the path to the coast continues to run westward and a point or two south through country typical of Africa’s central plateau. There are the usual wind-swept spaces of bog and yellow grass, the usual rolling lines of scrubby forest, and the shallow valleys with narrow channels of water running through morass. The path skirts the northern edge of the high, wet plain of Bouru-Bouru, and on the same day, after passing this, I saw far away in the west a little blue point of mountain, hanging like an island upon the horizon. A few hours afterwards bare rock began to appear through the bog-earth and sand of the forest, and next morning new mountains came into sight from hour to hour as I advanced, till there was quite a cluster of little blue islands above the dark edges of the trees.

The day after, when I had been walking for about two hours through the monotonous woods, the upland suddenly broke. It was quick and unexpected as the snapping of a bowstring, and far below me was revealed a great expanse of country—broad valleys leading far away to the west and north, isolated groups of many-colored mountains, bare and shapely hills of granite and sandstone, and one big, jagged tooth or pike of purple rock, rising sheer from a white plain thinly sprinkled with trees and marked with watercourses. The whole scene, bare and glowing under the cloudless sky of an African winter, was like those delicate landscapes in nature’s most friendly wilderness which the Umbrians used to paint as backgrounds to the Baptist or St. Jerome or a Mother and Child. To one who has spent many months among the black forest, the marshes and sand-hills of Bihé and the Hungry Country, it gleams with a radiance of jewels, and is full of the inward stir and longing that the sudden vision of mountains always brings.[7]

At the top of the hill was a large sweet-potato plantation for rum. A gang of twenty-three slaves—chiefly women—was clearing a new patch from the bush for an extension of the fields. Over them, as usual, stood a Portuguese ganger, who encouraged their efforts with blows from a long black chicote, or hippo whip, which he rapidly tried to conceal down his trousers leg at sight of me.

At the foot of the hill, where a copious stream of water ran, a similar rum-factory had just been constructed. The hideous main building—gaunt as a Yorkshire mill—the whitewashed rows of slave-huts, the newly broken fields, the barrels just beginning to send out a loathsome stench of new spirit—all were as fresh and vile as civilization could make them. As we passed, the slaves were just enjoying a holiday for the burial of one of their number who had died that morning. They were gathered in a large crowd round the grave on the edge of the bush. Presently six of them brought out the body, wrapped in an old blanket, rolled it sideways into the shallow trench, and covered it up with earth and stones. As we climbed the next hill, my carriers, who were much interested, kept saying to one another: “Slaves! Poor slaves!” Then we heard a bell ring. The people began to crawl back to their work. The slaves’ holiday was over.

We had now passed from Bihé into the district of Bailundu, and the mountains stood around us as we descended, their summits rising little higher than the level of the Bihéan plateau—say five to six thousand feet above the sea. A detached hill in front of us was conspicuous for its fortified look. From the distance it was like one of the castellated rocks of southern France. It was the old Umbala, or king’s fortress, of Bailundu, and here the native kings used to live in savage magnificence before the curse of the white men fell. On the summit you still may see the king’s throne of three great rocks, the heading-stone where his enemies suffered, the stone of refuge to which a runaway might cling and gain mercy by declaring himself the king’s slave, the royal tombs with patterned walls hidden in a depth of trees, and the great flat rock where the women used to dance in welcome to their warriors returning from victory. One day I scrambled up and saw it all in company with a man who remembered the place in its high estate and had often sat beside the king in judgment. But all the glory is departed now. The palace was destroyed and burned in 1896. The rock of refuge and the royal throne are grown over with tall grasses. Leopards and snakes possess them merely, and it is difficult even to fight one’s way up the royal ascent through the tangle of the creepers and bush.[8]

At the foot of the hill, within a square of ditch and rampart, stands the Portuguese fort, the scene of the so-called “Bailundu war” of 1902. It was here that the native rising began, owing to a characteristic piece of Portuguese treachery, the Commandant having seized a party of native chiefs who were visiting him, at his own invitation, under promise of peace and safe-conduct. The whole affair was paltry and wretched. The natives displayed their usual inability to combine; the Portuguese displayed their usual cowardice. But, as I have shown before, the effect of the outbreak was undoubtedly to reduce the horrors of the slave-trade for a time. The overwhelming terror of the slave-traders and other Portuguese, who crept into hiding to shelter their precious lives, showed them they had gone too far. The atrocious history of Portuguese cruelty and official greed which reached Lisbon at last did certainly have some effect upon the national conscience. As I have mentioned in earlier letters, Captain Amorim of the artillery was sent out to mitigate the abominations of the trade, and for a time, at all events, he succeeded. Owing to terror, the export of slaves to San Thomé ceased altogether for about six months after the rising. It has gone back to its old proportions now—the numbers averaging about four thousand head a year (not including babies), and gradually rising.[9] But since then the traders have not dared to practise the same open cruelties as before, and the new regulations for slave-traffic—known as the Decree of January 29, 1903—do, at all events, aim at tempering the worst abuses, though their most important provisions are invariably evaded.

Only a mile or two from the fort, and quite visible from the rocks of the old Umbala, stands the American mission village of Bailundu—I believe the oldest mission in Angola except the early Jesuits’. It was founded in 1881, and for more than twenty years has been carried on by Mr. Stover and Mr. Fay, who are still conducting it. The Portuguese instigated the natives to drive them out once, and have wildly accused them of stirring up war, protecting the natives, and other crimes. But the mission has prospered in spite of all, and its village is now, I think, the prettiest in Angola. How long it may remain in its present beautiful situation one cannot say. Twenty years ago it was surrounded only by natives, but now the Portuguese have crept up to it with their rum and plantations and slavery, and where the Portuguese come neither natives nor missions can hope to stay long. It may be that in a year or two the village will be deserted, as the American mission village of Saccanjimba, a few days farther east, has lately been deserted, and the houses will be occupied by Portuguese convicts with a license to trade, while the church becomes a rum-store. In that case the missionaries will be wise to choose a place outside the fifty-kilometre radius from a fort, beyond which limit no Portuguese trader may settle. So true it is that in modern Africa an honest man has only the whites to fear. But unhappily new forts are now being constructed at two or three points along this very road.

Soon after leaving Bailundu the track divides, and one branch of it runs northwest, past the foot of that toothed mountain, or pike,[10] and so at length reaches the coast at Novo Redondo—a small place with a few sugar-cane plantations for rum and a government agency for slaves. I am told that on this road the slaves are worse treated and more frequently shackled than upon the path I followed, and certainly Novo Redondo is more secret and freer from the interference of foreigners than Benguela. But I think there cannot really be much difference. The majority of slaves are still brought down the old Benguela route, and scattered along it at intervals I have found quite new shackles, still used for pinning the slaves together, chiefly at night, though it is true the shackles near the coast are not nearly so numerous as in the interior.

I was myself determined to follow the old track and come down to the sea by that white path where I had seen the carriers ascending and descending the mountains above Katumbella many months before. Within two days from Bailundu I entered a notorious lion country. Lions are increasing rapidly all along the belt of mountains here, and they do not hesitate to eat mankind, making no prejudiced distinction between white and black. Their general method is to spring into a rest-hut at night and drag off a carrier, or sometimes two, while the camp is asleep. All the rest-camps in this district are strongly stockaded with logs, twelve or fourteen feet high, but carriers are frequently killed in spite of all the stockade. There is one old lion who has made quite a reputation as a man-hunter, and if he had an ancestral hall he could decorate it with the “trophies” of about fifty human heads. He has chosen for his hunting-lodge some cave near the next fort westward from Bailundu, and there at eve he may sometimes be seen at play upon the green. Two officers are stationed in the fort, but they do not care to interfere with the creature’s habits and pursuits. They do not even train their little toy gun on him. Perhaps they are humanitarians. So he devours mankind at leisure.

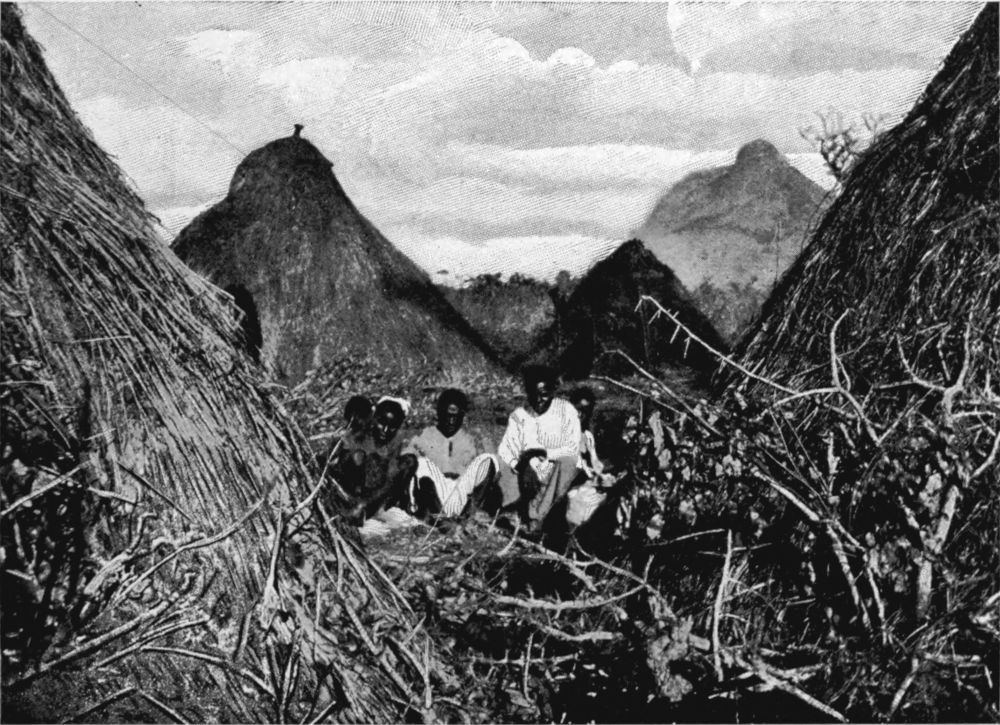

CARRIERS’ REST-HUTS

When we camped near that fort, my boys insisted I should sleep in a hut inside the stockade instead of half a mile away from them as usual. The huts are made of dry branches covered with dry leaves and grass. Inside that stockade I counted over forty huts, and each hut was crammed with carriers—men, women, and children—for the dry-season trade was beginning. There must have been five or six hundred natives in that camp at night. The stockade rose fourteen feet or more and was impenetrable. The one gate was sealed and barred with enormous logs to keep out the lion. I was myself given a hut in the very centre of the camp as an honor. And in every single hut around me a brilliant fire was lighted for cooking and to keep the carriers warm all night. One spark gone wrong would have burned up the whole five hundred of us without a chance of escape. So when we came to the stockaded camp of the next night I pitched my tent far outside it as usual, and listened to the deep sighing and purring of the lions with great indifference, while the boys marvelled at a rashness which was nothing to their own.

As one goes westward farther into the mountains, the path drops two or three times by sudden, steep descents, like flights of steps down terraces, and at each descent the air becomes closer and the plants and beasts more tropical, till one reaches the deep valleys of the palm, the metallic butterfly, and thousands of yellow monkeys. Beside the route great masses of granite rise, weathered into smooth and unclimbable surface, like the Matopo hills. The carriers from the high interior suffer a good deal at each descent. “We have lost our proper breathing,” they say, and they pine till they return to the clearer air. It is here that many of the slaves try to escape. If they got away, there would not be much chance for them among the shy and apelike natives of the mountain belt, who remain entirely savage and are reputed to be cannibal still. But the slaves try to escape, and are generally brought back to a fate worse than being killed and eaten. On May 17th, five days above Katumbella, I met one of them who had been caught. He was a big Luvale man, naked, his skin torn and bleeding from his wild rush through thorns and rocks. In front and behind him marched one of his owner’s slaves with drawn knives or matchets, two feet long, ready to cut him down if he tried to run again. I asked my boys what would happen to him, and they said he would be flogged to death before the others. I cannot say. I should have thought he was too valuable to kill. He must have been worth over £20 as he stood, and £30 when landed at San Thomé. But, of course, the trader may have thought it would pay better to flog him to death as an example. True, it is not always safe to kill a slave. Last April a man in Benguela flogged a slave to death with a hippo whip, and, no doubt to his great astonishment, he found himself arrested and banished for a time to Mozambique—“the other coast,” as it is called—a far from salubrious home. But five days’ inland along the caravan route the murderer of a slave would be absolutely secure, if he did not mind the loss of the money.

Two days later I met another of those vast caravans of natives, one of which I had seen just the other side of the Cuanza. This caravan numbered nearly seven hundred people, and, under the protection of an enormous Portuguese banner, they were marching up into the interior with bales and stores, wives and children, intending to be absent at least two years for trade. These large bodies of men are a great source of supply to the government slave-agents; for when they find two tribes at war, they hire themselves out to fight for one on condition of selling the captives from the other, and so they secure an immense profit for themselves, while pleasing their allies and bringing an abundance of slaves for the Portuguese government to “redeem” by sending them to labor at San Thomé till their lives end.

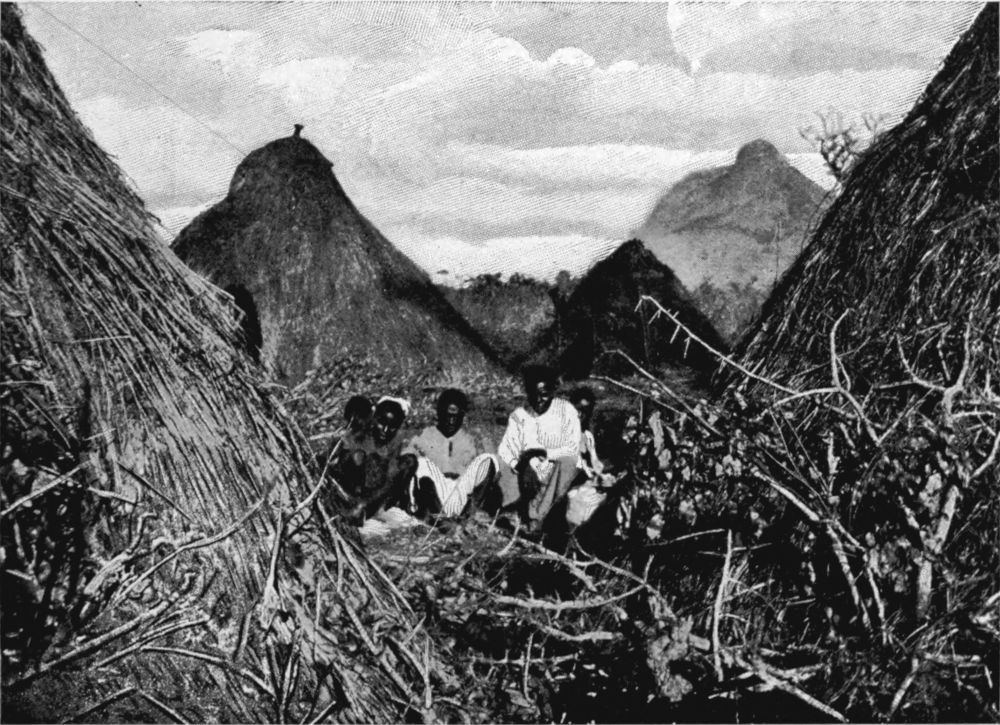

The next day’s march brought us to a straight piece of valley, where such a number of rest-huts have been gradually built that the place looks like a large native village. All the little paths from the interior meet here, because it stands at the mouth of a long and very deep valley, sometimes called the cañon, by which alone the next belt of dry and mountainous country can be crossed. The water is dirty and full of sulphur, but it has to be carried in gourds for the next day’s march, because for twenty-five miles there is no water at all.

Natives here come down from the nearest villages and sell sweet-potatoes and maize to the carriers in exchange for salt and chips of tobacco or sips of rum, so that at this season, when the carriers every night number a thousand or more, there is something like a fair. Mixed up with the carriers are the small gangs of slaves, who are collected here in larger parties before being sent on to the coast.

With the help of one of my boys I had some conversation that evening with a woman who was kept waiting for other gangs, just as I was kept waiting because fever made me too weak to move. She was a beautiful woman of about twenty or little more, with a deep-brown skin and a face of much intelligence, full of sorrow. She had come from a very long way off, she said—far beyond the Hungry Country. She thought four moons had gone since they started. She had a husband and three children at home, but was seized by the men of another tribe and sold to a white man for twenty cartridges. She did not know what kind of cartridges they were—they were “things for a gun.” Her last baby was very young, very young. She was still suckling him when they took her away. She did not know where she was going. She supposed it was to Okalunga—a name which the natives use equally for hell or the abyss of death, the abyss of the sea and for San Thomé. She was perfectly right. She was one of the slaves who had been purchased, probably on the Congo frontier, on purpose for the Portuguese government’s agent to “redeem” and send to the plantations. It is a lucrative business to supply such philanthropists with slaves. And it is equally lucrative for the philanthropists to redeem them.

The long, dry cañon, where the carriers have to climb like goats from rock to rock along the steep mountain-side, with fifty or sixty pounds on their heads, brought us at last to a brimming reach of the Katumbella River. It is dangerous both from hippos and crocodiles; though the largest crocodiles I have ever seen were lower down the river, on the sand-banks close to its mouth, where they devour women and cattle, and lie basking all their length of twenty to thirty feet, just like the dragons of old. From the river the path mounts again for the final day’s march through an utterly desert and waterless region of mountain ridges and stones and sand, sprinkled with cactus and aloes and a few gray thorns. But, like all this mountain region, the desert gives ample shelter to eland, koodoo, and other deer. Buffaloes live there, too, and in very dry seasons they come down at night to drink at the river pools close to the sea.

The sea itself is hidden from the path by successive ridges of mountain till the very last edge is reached. On the morning of my last day’s trek a heavy, wet mist lay over all the valleys, and it was only when we climbed that we could see the mountain-tops, rising clear above it in the sunshine. But before mid-day the mist had gone, and, looking back from a high pass, I had my last view over the road we had travelled, and far away towards the interior of the strange continent I was leaving. Then we went on westward, and climbed the steep and rocky track over the final range, till at last a great space of varied prospect lay stretched out below us—the little houses of Katumbella at our feet, the fertile plain beside its river green with trees and plantations; on our right the white ring of Lobito Bay, Angola’s future port; on our left a line of yellow beach like a road leading to the little white church and the houses of Benguela, fifteen miles away; and beyond them again to the desert promontory, with grotesque rocks. And there, far away in front, like a vast gulf of dim and misty blue, merging in the sky without a trace of horizon, stretched the sea itself; and to an Englishman the sea is always the way home.

So, as I had hoped, I came down at last from the mountains into Katumbella by that white path which has been consecrated by so much misery. And as I walked through the dimly lighted streets and beside the great court-yards of the town that night, I heard again the blows of the palmatoria and chicote and the cries of men and women who were being “tamed.”

“I do not trouble to beat my slaves much—I mean my contracted laborers,” said the trader who was with me. “If they try to run away or anything, I just give them one good flogging, and then sell them to the Agent for San Thomé. One can always get £16 per head from him.”

A few days afterwards, on the Benguela road, I passed a procession of forty-three men and women, marching in file like carriers, but with no loads on their heads. Four natives in white coats and armed with guns accompanied them, ready to shoot down any runaway. The forty-three were a certain company’s detachment of “voluntary laborers” on their way to the head “Emigration Agent” at Benguela and to the ship for San Thomé. Third among them marched that woman who had been taken from her husband and three children and sold for twenty cartridges.

Thus it is that the islands of San Thomé and Principe have been rendered about the most profitable bits of the earth’s surface, and England and America can get their chocolate and cocoa cheap.