CHAPTER FIVE

The Marshes

THE stretch between Gravesend and the beginnings of the Metropolis can scarcely be regarded as an interesting portion of the River. True, there are one or two places which stand out from the commonplace level, but for the most part there is nothing much to attract; and certainly from the point of view of the navigator of big ships there is much in this stretch to repel, for here are to be found the numerous shoals which tend to make the passage of the River so difficult.

Indeed, the problem of the constant filling of the bed of the River has always been a difficult one with the authorities. The River brings down a tremendous quantity of material (it is estimated that 1,000 tons of carbonate of lime pass beneath Kingston Bridge each day), and the tides bring in immense amounts of sand and gravel. Now, what becomes of all this insoluble material? It passes on, carried by the stream or the tidal waters, till it reaches the parts of the River where the downflowing stream and the incoming sea-water are in conflict, and so neutralize each other that there is no great flow of water. Then, no longer impelled, the material sinks to the bottom and forms great banks of sand, etc., which would in time grow to such an extent that navigation would be impeded, were not dredgers constantly engaged in the work of clearing the passage. It was largely this obstacle to efficient navigation that led to the creation of the great deep-sea docks at Tilbury.

Northfleet, formerly a small village straggling up the side of a chalk hill, is now to all intents a suburb of Gravesend, so largely has each grown in recent years. Here, officially at any rate, are situated (about a mile to the west of Gravesend proper) those notorious Rosherville Gardens which in the middle of last century made Gravesend famous, and provided Londoners with a plausible reason for a trip down the River. The gardens were laid out in 1830 to 1835 by one Jeremiah Rosher, several disused chalk-pits being used for the purpose; and here the jovial Cockney visitors regaled themselves within quaint little arbours with tea and the famous Gravesend shrimps, and later danced to the light of Chinese lanterns till it was time to return citywards from the day’s high jinks.

The Dockyard at Northfleet, constructed towards the end of the eighteenth century, was at one time a place of considerable importance, for here were built and launched numbers of fine vessels, both on behalf of the Royal Navy and of the East India Company. Now it has dwindled to comparative insignificance. Indeed, from a shipping point of view, the only interest lies in the numerous and familiar tan-sailed barges of the Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers; for Northfleet is one of the main centres of the cement industry so far as the Thames-side is concerned—an industry which is in evidence right along this stretch till the chalk hills end at Greenhithe, the town from which Sir John Franklin set out in 1845 on his illfated expedition to the North-West Passage.

At Grays (or Grays Thurrock, as it is more properly called), on the Essex bank, are numbers of those curious subterranean chalk caves which are a feature of most of the chalk uplands on both sides of the River, and which have caused so much discussion among the archæologists. These consist of vertical shafts, 3 or 4 feet in diameter, dug down through anything from 50 to 100 feet of sand into the chalk below, where they widen out into caves 20 or more feet long. As many as seventy-two of them have been counted within a space of 4 acres in the Hangman’s Wood at Grays. What they were for no one can tell. All sorts of things have been conjectured, from the fabulous gold-mines of Cunobeline to the smugglers’ refuges of comparatively modern times. One thing is certain: they are of tremendous age. Probably they were used by their makers mainly as secret storehouses for grain. They are commonly called Dene-holes or Dane-holes, and are said to have served as hiding-places in that hazardous period when the Danes made life in the valley anything but pleasant. But this, while it may have been true, in no way solves the mystery of their origin.

Purfleet, especially from a distance, is by no means unattractive, for quite close to the station a wooded knoll, quaintly named Botany, rises from the general flatness, and its greenery, contrasting strongly with the white of the chalk-pits, lifts the town out of that dreariness, merging into the positively ugly, which is the keynote of this part of the River beside the Long and Fiddler’s Reaches. The Government powder-magazine sets the fashion in beauty along a stretch which includes lime-kilns, rubbish heaps of all sorts, and various small and dingy works. Here at Purfleet (and also at Thames Haven, lower down the River) have in recent years been set down great installations for the storage of petrol and other liquid fuels—a riverside innovation of great and increasing importance.

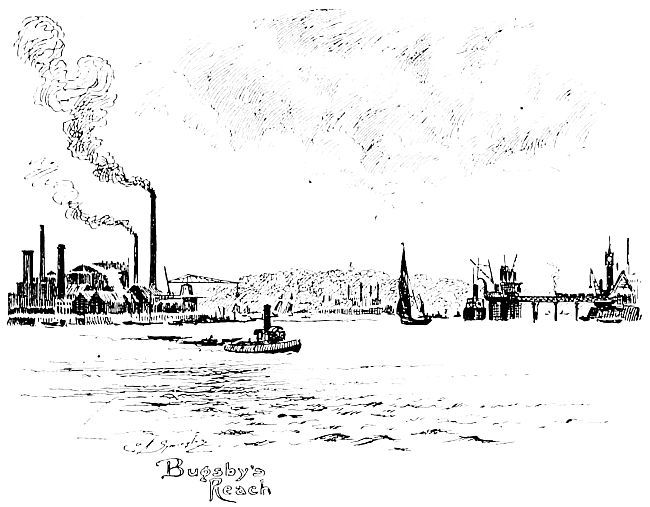

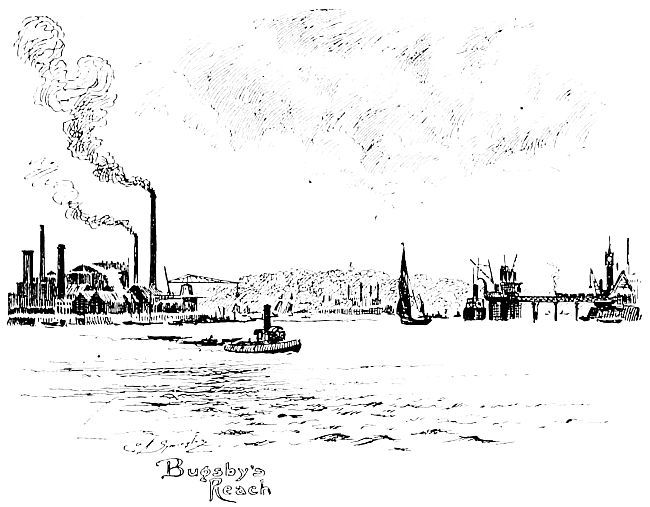

Bugsby’s Reach

To the west of Purfleet lies a vast stretch of flats, known as Dagenham Marshes, in many places considerably lower than the level of the River at high tide, but protected from its advances by the great river-wall. Apparently the wall at this spot must have been particularly weak, for right through the Middle Ages and onwards we find it recorded that great stretches of the meadows were laid under water owing to the irruption of the tidal waters into the wall. There were serious inundations in 1376, 1380, and 1381, when the landowners combined to effect repairs. Again in 1594 and 1595 there was a serious failure of the dyke, with the result that the whole adjacent flats were covered twice a day. Now, this in itself would not have been so extremely serious; but the constant passing in and out of the water caused a deep hole to be washed out just inside the wall, and made the material bank up and form a bar on the opposite side of the stream. For a quarter of a century nothing was done, but eventually the Dutchman Vermuyden was called in, and he repaired the wall successfully. But in the days of Anne came an even more serious irruption, when the famous Dagenham breach was formed. One night in the year 1707, owing to the carelessness of the official in charge, the waters broke the dyke once more, and swamped an area of a thousand acres or more, doing a vast deal of mischief. Once again the danger to navigation occurred, as the gravel, etc., swept out at each tide, formed a shoal half-way across the River, and fully a mile in length. So dangerous, indeed, was it that Parliament stepped in to find the £40,000 needed for the repairs—a sum which the owners of the land could not have found. The waters were partially drained off, and the bank repaired; but a very big lake remained behind the wall, and remains to this day, as most anglers are aware.

Towards the end of last century a scheme was set on foot for the construction of an immense dock here, because, it was urged, the excavations already done by the water would render the cost of construction smaller. Parliament agreed to the proposal, and it appeared as if this lonely part of Essex might become a great commercial centre; but the construction of the Tilbury Docks effectively put an end to the scheme. Now there is a Dagenham Dock, but it is merely a fair-sized wharf, engaged for the most part in the coal trade.

Barking stands on the River Roding, a tributary which comes down by way of Ongar from the Hatfield Forest district near Epping, and which, before it joins the main River, widens out to form Barking Creek, which was, before the rise of Grimsby, the great fishing harbour.

Barking is a place of great antiquity, and of great historic interest, though one would scarcely gather as much from a casual glance at its very ordinary streets with their commonplace shops and rows of drab houses—just as one would scarcely gather any idea of the charm of the Roding at Ongar and above from a glimpse of the slimy Creek. The town, in fact, goes even so far as to challenge the rival claims of Westminster and the City to contain the site of the earliest settlements of prehistoric man along the River valley. And certainly the earthworks discovered on the north side of the town—fortifications more than forty acres in extent and quite probably of Ancient British origin—even if they do not justify the actual claim, at least support the town in its contention that it is a place of great age.

Little or nothing is known, however, till we come to the time of the foundation of its Abbey in the year 670. In that year, perhaps by reason of its solitude out there in the marshes, the place appealed to St. Erkenwald, the Bishop of London, as a good place for a monastic institution, and the great Benedictine Abbey of the Blessed Virgin, the first English convent for women, arose from the low-lying fenlands, and started its life under the direction of the founder’s sister, St. Ethelburgha.

It was destroyed by the Danes when they ventured up river in the year 870, but was rebuilt by King Edgar, after lying practically desolate for a century. By the time of the Conquest it had become a place of very great importance in the land, and to it came William after the treaty with the citizens of London, and to it he returned when his coronation was over, and there established his Court till such time as the White Tower should be finished by the monk Gundulf and his builders.

Certainly it is a strange commentary on the irony of Time that this present-day desolation of drab streets should once have been the centre of fashion, to which came all the nobles in the south of England, bringing their ladies fair, decked out in gay apparel to appear before the King.

In 1376 the Abbey met with its first great misfortune. In that year Nature conspired to the undoing of man’s great handiwork on the River, and the tide made a great breach at Dagenham, thereby causing the flooding of many acres of the Abbey lands, and driving the nuns from their home to higher ground at Billericay. So much was the prosperity of the Abbey affected by this disaster that the Convent of the Holy Trinity, in London, granted the Abbess the sum of twenty pounds annually (a large sum in those days) to help with the reclaiming of the land.

Now of all the fine buildings of the Abbey practically nothing is left. At the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries it passed into the King’s hands, and was afterwards sold to Lord Clinton. It has since gone through many ownerships, but no one has seen fit to preserve it. So that now practically all we can find is a sadly disfigured gateway at the entrance to the churchyard. This was at one time referred to as the “Chapel of the Holy Rood Loft atte Gate,” but the name was afterwards changed to the more conveniently spoken “Fire-bell Gate.” Of the actual Abbey buildings nothing remains.

The London church of All Hallows, Barking, standing at the eastern end of Tower Street, quite close to Mark Lane Station, bears witness to the privileges and great power of the nunnery in ancient days, for the church was probably founded by the Abbey, and certainly the patronage of the living was in the hands of the Abbess from the end of the fourteenth century to the time of the suppression of the monasteries.

Just to the west of the Creek mouth is the outfall of the northern drainage system of London. Vast quantities of sewage are brought daily, by means of a gigantic concrete outfall sewer, which passes across the flats from Old Ford and West Ham to Barking; and there they are deposited in huge reservoirs covering ten acres of ground. The sewage passes through four great compartments which together hold thirty-nine million gallons; and, having been rendered more or less innocuous, is discharged into the Thames at high tide. This arrangement was one of the chief objections urged against the great barrage at Gravesend.