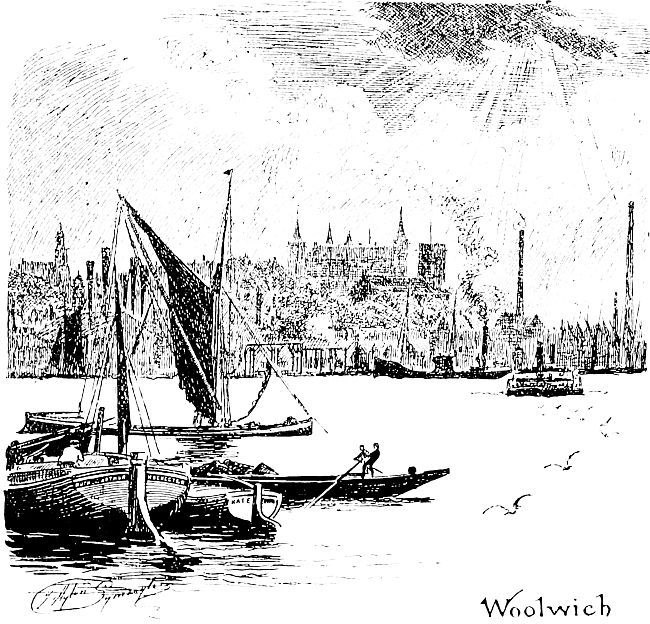

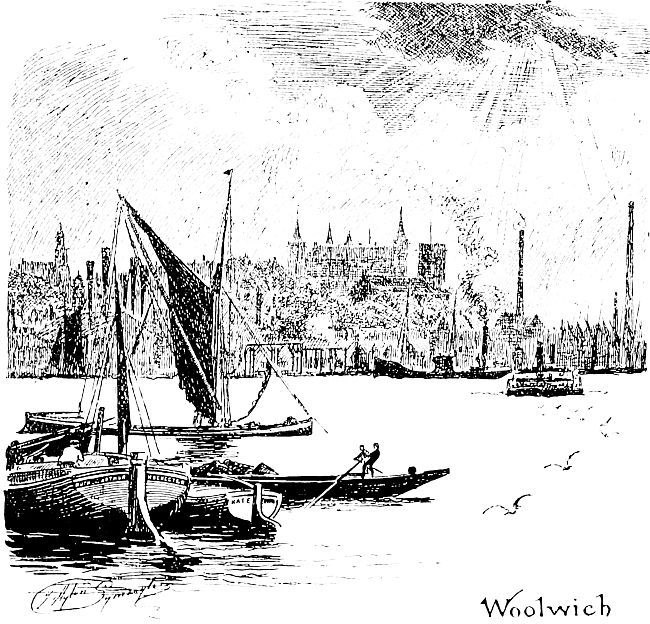

CHAPTER SIX

Woolwich

FOR many years there was a local saying to the effect that “more wealth passes through Woolwich than through any other town in the world,” and, though at first sight this may seem a gross exaggeration, yet when we remember that Woolwich is in two parts, one on each side of the River, we can see at once the justice of that claim, for it simply meant that all the vast traffic to and from the Pool of London went along the Thames as it flowed between the two divisions of the town.

To-day as we look at the drab, uninteresting place which occupies the sloping ground extending up Shooter’s Hill and the riverside extent from Charlton to Plumstead, we find it difficult to believe that this was ever a place of such great charm that London folk found in it a favourite summer-time resort. Yet we have only to turn up the “Diary” of good old Pepys to read (May 28, 1667): “My wife away down with Jane and Mr. Hewer to Woolwich, in order to a little ayre, and to lie there to-night, and so to gather may-dew to-morrow morning, which Mrs. Yarner hath taught her is the only thing in the world to wash her face with; and I am contented with it.”

Of course, in those days Woolwich was in the country, surrounded by fields and woods, in the latter of which lurked footpads ever ready to relieve the unwary traveller of his purse. Thus we have Pepys writing in 1662: “To Deptford and Woolwich Yard. At night, I walked by brave moonlight with three or four armed men to guard me, to Rotherhithe, it being a joy to my heart to think of the condition that I was now in, that people should of themselves provide this for me, unspoke to. I hear this walk is dangerous to walk by night, and much robbery committed there”; and again in 1664: “By water to Woolwich, and walked back from Woolwich to Greenwich all alone; saw a man that had a cudgel, and though he told me he laboured in the King’s yard, yet, God forgive me! I did doubt he might knock me on the head behind with his club.”

Woolwich

Even a hundred years ago Woolwich was a comparatively small place, consisting largely of the one main street, the High Street, with smaller ways running down to the riverside. Shooter’s Hill was then merely wild heathland, ill-reputed as the haunt of highwaymen.

Yet, for all that, Woolwich has been an important place through long years, for here have existed for centuries various Government factories and storehouses—at first the dockyards, and afterwards the Arsenal.

Just when the dockyards were founded it is difficult to say, but it is generally agreed that it was either at the end of the reign of Henry VII. or at the beginning of that of Henry VIII. Certain it is that from the latter’s reign down to the early days of Victoria the dockyard flourished. From its slips were launched many of the most famous of the early old “wooden walls of England”—the Great Harry (afterwards called the Henry Grace de Dieu), the Prince Royal, the Sovereign Royal, and also many of those made famous by the glorious victories of Drake and Cavendish, and in the wonderful voyages of Hawkins and Frobisher. The Sovereign Royal, which was launched in the time of Charles I., was a fine ship of over 1,600 tons burden, and carried no less than a hundred guns. “This royal ship,” says old Stow, “was curiously carved, and gilt with gold, so that when she was in the engagement against the Dutch they gave her the name of the ‘Golden Devil,’ her guns, being whole cannon, making such havoc and slaughter among them.”

With the passing away of the “wooden walls” and the advent of those huge masses of steel and iron which have in modern times taken the place of the picturesque old “three-deckers,” Woolwich began to decay as a Royal dockyard; for it soon became an unprofitable thing to build at Thames-side, and the shipbuilding industry migrated to towns nearer to the coalfields and the iron-smelting districts.

Yet Woolwich continued, and has continued right down to this very day, its activities as a gun-foundry and explosives factory. Just when this part of the Royal works was founded we do not know. There is a story extant (and for years the story was accepted as gospel) to the effect that the making of the Arsenal was due entirely to a disastrous explosion at Moorfields in the year 1716. Apparently much of the Government work in those days was put out to contract, and a certain factory in the Moorfields area took a considerable share in the work. On one occasion a very large crowd had assembled to witness the casting of some new and more up-to-date guns from the metal of those captured by the Duke of Marlborough. Just as everything was ready, a clever young Swiss engineer, named Schalch, noticed that the material in the moulds was wet, and he warned the authorities of the danger. No notice was taken, the molten metal was poured into the castings, and there was a tremendous explosion. According to the story, the authorities were so impressed by the part which Schalch had played in the matter that they appointed him to take charge of a new Government foundry, and gave him the choice of a site on which to build his new place, and he chose the Woolwich Warren, slightly to the east of the Royal Dockyards. This is a most interesting story, and one with an excellent moral, no doubt—such a story, in fact, as would have delighted the heart of old Samuel Smiles; but, unfortunately for its veracity, there have been discovered at Woolwich various records which prove the existence of the Arsenal before Schalch was born.

In normal times the Arsenal provides employment for more than eight thousand hands, but, of course, in war-time this number is increased tremendously. During the South African War, for instance, more than twenty thousand were kept on at full time, and the numbers during the Great War, when women were called in to assist and relieve the boys and men, were even greater.

Of course, we cannot see everything at Woolwich Arsenal. There are certain buildings in the immense area where strangers are never permitted to go. In these various experiments are being carried out, various new inventions tested, and for this work secrecy is essential. It would never do for a rival foreign Power to get even small details of a new gun, or explosive, or other warlike device. But still there is much that can be seen (after permission to visit has been obtained from the War Office)—remarkable machines which turn out with amazing rapidity the various parts of cartridges and shells; giant rolling machines and steam-hammers that fashion the huge blocks of steel, and tremendous machines that convert them into huge guns; machines by which gun-carriages and ammunition-waggons are turned out by the dozen.

Half a century ago there was a great stir at Woolwich when the Arsenal turned out for the arming of the good ship Hercules a new gun known as the “Woolwich Infant.” This weapon, which required a fifty-pound charge of powder, could throw a projectile weighing over two hundredweights just about six miles, and could cause a shell to pierce armour more than a foot thick at a distance of a mile. Naturally, folk in those days thought them terrible weapons. But the “infants” were soon superseded, for a few years later Woolwich turned out what were known as “eighty-one-ton guns”—deadly weapons which could fire a shell weighing twelve hundred pounds. Folk lifted their hands in surprise at the attainments of those days; but it is difficult to imagine their amazement if they could have seen our present-day guns firing shells thirty miles, or the great “Big Bertha,” by means of which the Germans fired shots from a distance of seventy miles into Paris.

The tremendous guns of to-day are built up, not cast in moulds all in one piece, as were those in the early years of the Woolwich foundry. There is an inner tube and an outer, the latter of which is shrunk on to the former. The larger tube is heated, and of course the metal expands. While it is in that condition the other is placed inside, and the whole thing is lowered by tremendous cranes into a big bath of oil. The metal contracts again as it cools, and in that way the outer tube is fixed so tightly against the inner that they become practically one single tube, but with greatly added strength. The tube is then carried to a giant lathe, where it receives the rifling on its inner surface.

When we turn away from Woolwich it is perhaps with something like a sigh to think that men will spend all this money, and devote all this time and labour and material, merely in order that they may be able to blow each other to pieces.