CHAPTER SEVEN

The Tower of London

LONDON has many treasures to show us, if we take the trouble to look for them, but it has no relic of the past so perfect as its Tower—a place which every Briton, especially every Londoner, ought to see and try to understand.

If only the Tower’s silent old stones could suddenly gain the power of speech, what strange tales they would have to tell of the things which have occurred during their centuries of history—tales of things glorious and tales of things unspeakably tragic. Though the latter would easily outweigh the former in number, I am afraid; for this grim stronghold is a monument to evil rather than to good.

The Tower has often been spoken of as the key to London, and there is truth in the saying, for its position is certainly an excellent one. When William of Normandy descended on England with his great company of knights and their retainers, he professed to have every consideration for the people of London, and certainly he treated the citizens quite fairly according to the terms of the treaty. But, at the same time, he apparently did not feel any too sure of them, and so he called in the monk, Gundulf, to erect a fortress, which to all appearances was merely a strengthening of the fortifications already there, but which in reality was intended to serve as a constant reminder of the power and authority of the conquering king.

The spot chosen was the angle at the eastern corner, just where the wall turns sharply inland from the River, and no position round London could have been better chosen. In the first place it guarded London from the river approach, ready to hold off any enemy venturesome enough to sail up the Thames to attack the city. But also, and this undoubtedly was what was in the mind of the Conqueror, it frowned down on the city.

A formidable Norman Keep was erected, with walls 15 feet thick, so strongly built that they stand to-day practically as they stood 900 years ago, save that stone-faced windows were put in a couple of centuries ago to take the place of the narrow slits or loopholes which served for light and ventilation in a fortress of this sort.

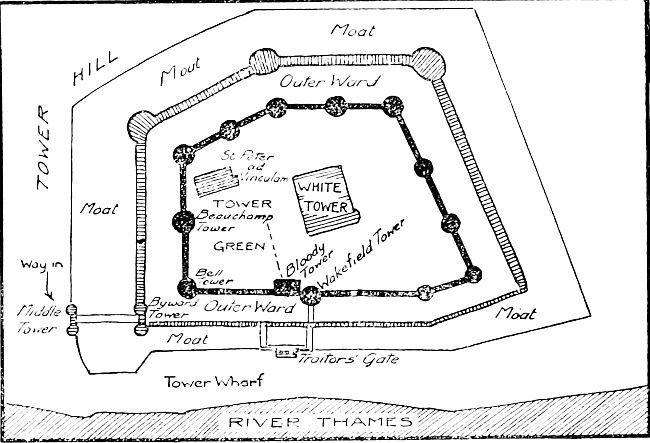

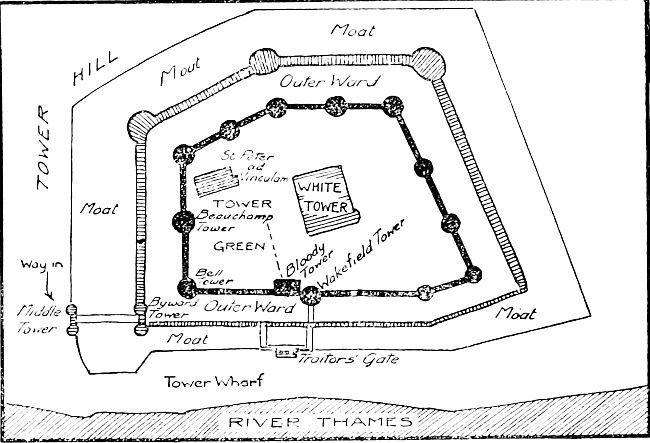

GROUND PLAN OF THE TOWER.

To understand the Tower of London properly (and we really want some idea of it before any visit, otherwise it is merely a confusion of towers and open spaces without any meaning) we must realize that it consists of three separate lines of defences, all erected at different times. The innermost, the Keep or White Tower, we have touched upon. Beyond that, and separated from it by an open space known as the Inner Ward, is the first wall, with its twelve towers, among them the Beauchamp Tower, the Bell Tower, the Bloody Tower, and the Wakefield Tower. Then, beyond that again, and separated by another open space known as the Outer Ward, is yet another wall; and still beyond is the Moat, outside everything. So that any attacking army, having successfully negotiated the Moat, would find itself with the outer wall to scale and break, and within that another inner wall, 46 feet high. The garrison, driven back from these two, could even then retire to the innermost keep, with its walls 15 feet thick, and there hold out for a great length of time against the fiercest attacks. So that, you will readily see, the Tower was a fortress of tremendous strength in days before the use of heavy artillery.

The outer defences were added to William’s White Tower from time to time by various monarchs. The first or inner wall, 8 feet thick, begun in the Conqueror’s days, was added to and strengthened by Stephen, Henry II., and John. The outer wall and the Moat were completed by Henry II.; and the Tower thus took its present shape.

Most of our Sovereigns, from the Conqueror’s time right down to the Restoration, used the Tower of London. Kings and Queens who were powerful used it as a prison for their enemies; those who were weak and feared the people used it as a fortress for themselves. This latter use of the Tower was particularly instanced in the reign of Stephen—an illuminating chapter in the story of London.

Stephen, following the death of Henry I., was elected King by the Great Council, and duly crowned in London; but the barons soon saw that he was unfitted for the task of ruling, and they took sides with the Empress Matilda, hoping thereby to get nearer the independence they desired. Stephen for a time held his own with the aid of a number of trusty barons, but in 1139 he offended the Church by his rough treatment of the Bishops of Lincoln and Salisbury, and his supporters fell away. Consequently he was compelled in the following year to seek safety in the Tower, close to his loyal followers, the citizens of London.

Now the constable of the Tower in those days was one Geoffrey de Mandeville, about as unscrupulous and cruel a rascal as could be imagined. Stephen, to ensure his support, made him Earl of Essex, and for a time all went well. But when, following Stephen’s defeat and capture in 1141, the Empress Matilda moved to London to be crowned, Geoffrey de Mandeville had not the slightest compunction in taking sides with her, for which he was rewarded by the gift of castles, revenues, and the office of Sheriff of Essex. But Matilda offended the citizens of London to such an extent that they drove her from the city and attacked Mandeville in the Tower. Whereupon Mandeville, without any hesitation, transferred his allegiance to Maud of Boulogne, Stephen’s wife, who was rallying his scattered forces—which allegiance was purchased by making Mandeville the Sheriff of Hertfordshire, Middlesex, and London, as well. Nothing, however, could serve to make this treacherous man act straightly, and when later Stephen found him planning yet another revolt in favour of Matilda, he attacked him suddenly, took him prisoner, and removed him from all public affairs.

This chapter in English history is far from showing the English nobles in a good light, but it is exceedingly interesting as revealing the extent to which London was beginning to count in the kingdom.

To-day we enter from the city side by what is known as the Middle Tower—a renovated and modernized gateway, with a big, stone-carved Royal Arms above its arch. The name “Middle” strikes us as curious, seeing that it is the first protection on the landward side, until we remember or learn that originally there was another Tower, the Lion Tower, nearer the city (approximately where the refreshment room now stands) and separated from the Middle Tower by a drawbridge. But the Lion Tower disappeared many many years ago, and only two of the three outer defences remain, the Middle Tower and the Byward Tower, the latter reached by a permanent bridge over the Moat.

Once through the Byward Gateway and we are between the inner and outer defences. Leaving on our left the Bell Tower, a strong, irregular, octagonal tower, which gets its name from the turret whence curfew bell rings each night, we walk along parallel to the River, past the frowning gateway of the Bloody Tower on our left, with its low arch which originally gave the only entrance to the Inner Ward, and on our right, and exactly opposite, the Traitor’s Gate, the riverside passage through the outer walls. Skirting the Wakefield Tower, we pass through a comparatively modern opening, and so come upon the amazing Norman Keep of William the Conqueror.

This Keep is not quite square, though it appears to be, and no one of its four sides corresponds to any other. Its greatest measurements are from north to south 116 feet, and from east to west 96 feet. Inside, three cross walls, from 6 to 8 feet thick, divide each floor into three separate apartments of unequal sizes. It is a building complete in itself, with everything required for a fortress, a Royal dwelling, and a prison. Probably, as you walk about the cold, gloomy chambers, you will say to yourselves that you can understand the fortress and the prison parts, but that you could never imagine it as a dwelling. But you must remember that with coverings on the floor and with the bare walls hung with beautiful tapestries, as was the custom in early days, and with furniture in position, the apartments must have presented a much more comfortable appearance.

The first story, or main floor, was the place where abode the garrison—the men-at-arms and their officers; and above on the other two floors were the State apartments—St. John’s Chapel and the Banqueting Hall on the second story, and the great Council Chamber of the Sovereign on the third floor. Beneath were great dungeons, terrible places without light or ventilation, having in those days no entrance from the level ground, but reached only by that central staircase which rose from them to the roof.

In these days the Keep is largely used as an armoury; and we can gain a fine idea of the different kinds of armour worn in different periods, and of the weapons used and of the cruel implements of torture. It also contains several good models of the Tower at different times, and a short study of these will do much to get rid of the confusion which most folk feel as they hurry from tower to tower without any general idea of the place.

Leaving the ancient Keep, we cross the only wide open space of the fortress, a paved quadrangle which keeps its antique and now inappropriate name of Tower Green, where in bygone days some of the Tower’s most famous prisoners have paraded in solitude on the grass. Here, marked by a tablet, is the site of the scaffold where died Lady Jane Grey, Anne Boleyn, Katherine Howard, and other famous prisoners of State. It is a quiet, moody spot, where the black ravens of the Tower, as they stand sentinel beneath the sycamore trees, at times seem the only things in keeping with the sadness of the place.

To our right is the little Church of St. Peter ad Vinculam, which will be shown to us by one of the quaintly garbed “Beef-eaters” (if one can be spared from other duties), the famous Yeomen of the Guard who still wear the uniform designed in Henry the Eighth’s days. Concerning this little sanctuary Lord Macaulay wrote: “There is no sadder spot on earth.... Death is there associated with whatever is darkest in human nature and in human destiny, with the savage triumph of implacable enemies, with the inconstancy, the ingratitude, the cowardice of friends, with all the miseries of fallen greatness and of blighted fame. Thither have been carried through successive ages, by the rude hands of gaolers, without one mourner following, the bleeding relics of men who had been the captains of armies, the leaders of parties, the oracles of senates, and the ornaments of courts.”

Close together in a small space before the Altar, raised slightly above the level of the floor, lie the mortal remains of two Queens, Anne Boleyn and Katherine Howard, Margaret of Salisbury, last of the proud Plantagenets, Lord and Lady Rochford, the Dukes of Somerset, Northumberland, Monmouth, Suffolk, and Norfolk, the Earl of Essex, Lady Jane Grey, Lord Guilford Dudley, and Sir Thomas Overbury.

As we pass on and come to the Beauchamp Tower, and later to the Bloody Tower, we see the tiny prisons where these unfortunates, and many others, languished in confinement, waiting their tragic end, whiling away the weary hours by carving quaint inscriptions on the stone walls; and, in the latter, we are shown the tiny apartment where perished the little Princes at the instigation of their uncle, Richard III.

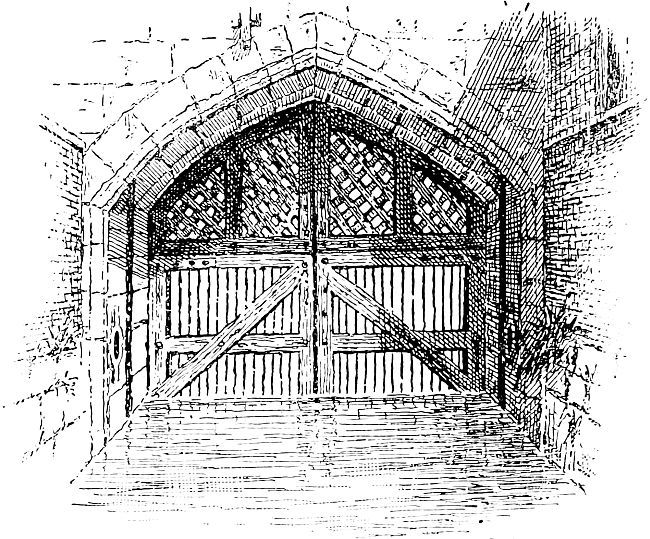

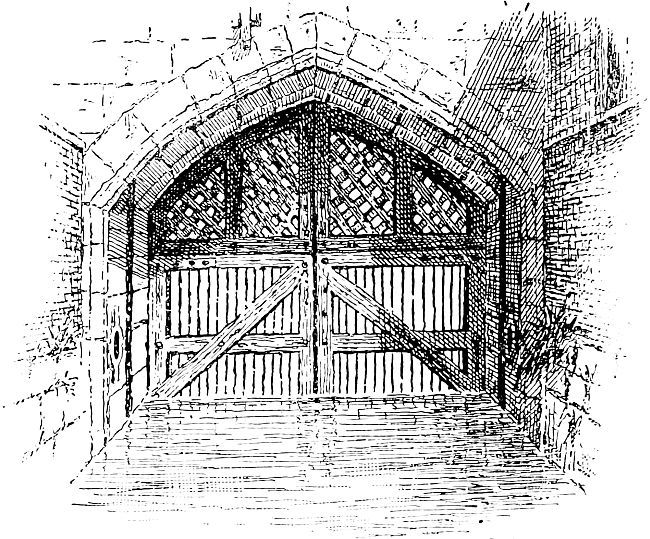

From our point of view there remains just one more thing to consider, and that is the Tower’s connection with the River. Probably few of us, as we try to think back through the centuries, realize how important the Thames was even as a highway. We know from our reading that London’s streets were narrow, crooked, and of very little use for a big amount of traffic; yet we do not see in our mind’s eye the great waterway which everybody, rich and poor, used in those days, alike for business and pleasure. And, of course, the Tower contributed very largely to this water traffic, for the King, his nobles, and all who had business at Westminster, travelled constantly to and fro in the great painted barges which made the River a gayer and brighter place than it is in our days. For the purpose of such travellers there was provided the Queen’s Steps at the Tower Wharf, in order to avoid the use of the sinister Traitor’s Gate—that low, frowning archway, which gave entrance from the River, and through which very many famous persons, innocent and guilty alike, passed to their doom, brought thither by water at the behest of the Sovereign.

TRAITOR’S GATE.

According to John Stow, who wrote in Elizabeth’s reign, the Tower was then “a citadel to defend or command the city; a royal palace for assemblies or treaties; a prison of state for the most dangerous offenders; the only place of coinage for all England at this time; the armoury for warlike provision; the treasury of the ornaments and jewels of the Crown; and general conserver of most records of the King’s courts of justice at Westminster.” All that is changed now. The Tower has long since ceased to be a Royal residence. As a defence of the city it would not last more than a few minutes against modern artillery. Save for the period of the great war, when it held the bodies of numerous spies and traitors and saw the execution of several, it has for many years given up its claim to be a prison. The records which filled the little Chapel of St. John have now been moved to the Record Office, and the making of money goes on at the Mint just across the road. The Crown Jewels still find a home here, in the Wakefield Tower, the prison where Henry VI. came to his violent end. Yet, despite all these changes, the fortress is still the Tower of London—perhaps the city’s most fascinating relic.