CHAPTER EIGHT

How Fire destroyed what the River had made

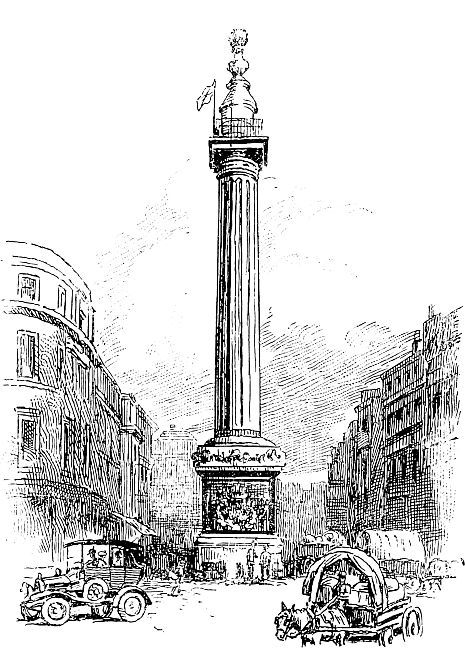

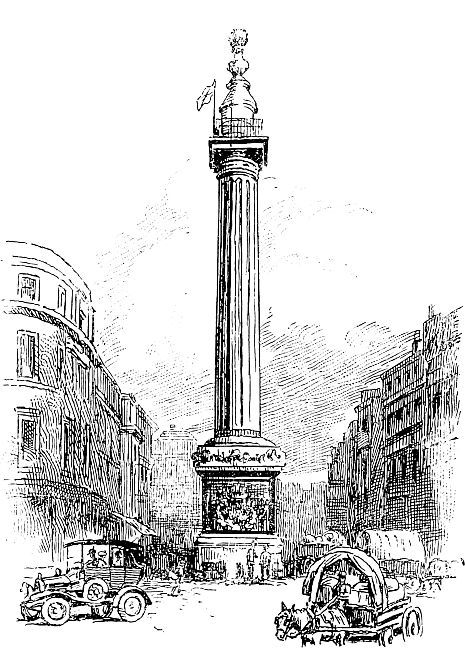

LEAVING the Tower by the Byward Gate, and passing along Great Tower Street and Eastcheap, we come to the spot

“Where London’s column pointing to the skies,

Like a tall bully, lifts its head and lies.”

This is, of course, the Monument, which for many years indicated to all and sundry that the Great Fire of 1666 was the work of the Roman Catholics. Till the year 1831 the inscription, added in 1681 at the time of the Titus Oates affair, perpetuated the lie in stone, but in that year it was removed by the City Council. Now the gilt urn with its flames, which we can see well if we ascend the 345 steps to the iron cage at the top, merely commemorates the Fire itself, without any reference to its cause, as in the original structure. From the top of the Monument we can get perhaps the very finest of all views of London and its River.

THE MONUMENT.

But there is one thing which should preface our account of the Great Fire, and that is an account of the Great Plague which visited and afflicted London in the previous year. Of course, the Fire was in one sense a terrible disaster for London, yet the destruction which it wrought was in reality a great blessing to the plague-ridden city.

The Plague, by no means the first to visit London, came over from the Continent, where for years it had been decimating the large cities. It broke out with terrible power in the summer of the year 1665—a dry, scorching summer which made the flushing of the open street drains an impossible thing, and gave every help to the dread pestilence. If we want to read a thrilling description of London at this time we have only to turn to the “Journal of the Plague Year,” by Defoe, the author of “Robinson Crusoe.” This was not actually a journal, for Defoe was only four years old in 1665, but it was a faithful account based on first-hand information. In its simply written pages (to quote from Sir Walter Besant) “we see the horror of the empty streets; we hear the cries and lamentations of those who are seized and those who are bereaved. The cart comes slowly along the streets with the man ringing a bell and crying, ‘Bring out your dead! Bring out your dead!’ We think of the great holes into which the dead were thrown in heaps and covered with a little earth; we think of the grass growing in the streets; the churches deserted; the roads black with fugitives hurrying from the abode of Death; we hear the frantic mirth of revellers snatching to-night a doubtful rapture, for to-morrow they die. The City is filled with despair.” As we can well imagine, the King and his courtiers fled from Whitehall and the Tower away into the country; the Law Courts were shifted up river to Oxford. Naturally all business stopped, and trade was at a standstill. Ships in hundreds lay idle in the Pool, waiting for the cargoes which came not, because the wharves and warehouses were deserted; laden ships that sailed up the Thames speedily turned about and made for the Continental ports. So it went on, the visitation increasing in fury, till in September there were nearly 900 fell each day. Then it abated slightly, but continued through the winter, on into the following summer, and in the end more than 97,000 people perished out of a population of 460,000.

Then, on September 2, came that other catastrophe, the Great Fire. Starting in a baker’s shop in Pudding Lane, near the Monument, it was driven westwards by a strong east wind.

The London of Stuart days gave the Fire every possible help. Not much survives to-day to show us what things were like, but the quaint, timber-fronted houses of Staple Inn (Holborn) and No. 17, Fleet Street, and the pictures painted at the time, give us a fair idea of the inflammable nature of the buildings; and when we remember that these wooden houses, old, dry, and coated with pitch, were in some streets so close to those opposite that it was possible to shake hands from the overhanging upper stories, we are not surprised at the rapidity with which the Fire spread.

The diaries of two gentlemen—Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn, the former one of the King’s Ministers, the latter a wealthy and learned gentleman of the Court—bring home to us plainly the terror of the seven days’ visitation. To begin with, very few took any special notice of the outbreak: fires were too common to cause great consternation. Even Pepys himself tells us that he returned to bed; but when the morning came and it was still burning, he was disturbed. Says he: “By and by Jane tells me that she hears that above 800 houses have been burned down to-night by the fire we saw, and that it is now burning down all Fish Street, by London Bridge. So I made myself ready presently, and walked to the Tower; and there got up upon one of the high places; and there I did see the houses at that end of the bridge all on fire, and an infinite great fire on this and the other side of the end of the bridge.”

London Bridge, as you will remember from a former chapter, was very narrow, and the houses projected out over the River, held in place by enormous timber struts; and these, with the wooden frames of the three-storied houses, gave the fire a good hold. Moreover the burning buildings, falling on the Bridge, blocked the way to any who would have fought the flames. After about a third of the buildings had been destroyed the fire was stopped by the pulling down of houses and the open space; but not before it had done great damage to the stone structure itself. The heat was so intense that arches and piers which had remained firm for centuries now began to show signs of falling to pieces, and it was found necessary to spend £1,500, an enormous sum in those days, on repairs before any rebuilding could be attempted.

Day after day the Fire continued. Says Evelyn: “It burned both in breadth and length, the churches, public halls, Exchange, hospitals, monuments, and ornaments, leaping after a prodigious manner from house to house and street to street, at great distances one from the other....

“Here we saw the Thames covered with goods floating, all the barges and boats laden with what some had time and courage to save, as, on the other, the carts, etc., carrying out to the fields, which for many miles were strewed with movables of all sorts, and tents erected to shelter both people and what goods they could get away....

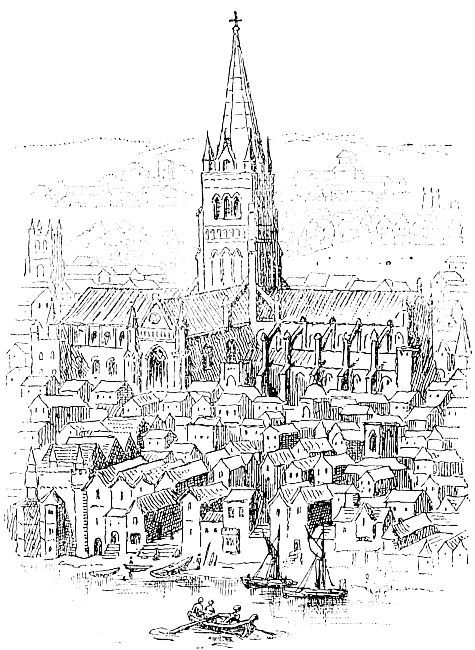

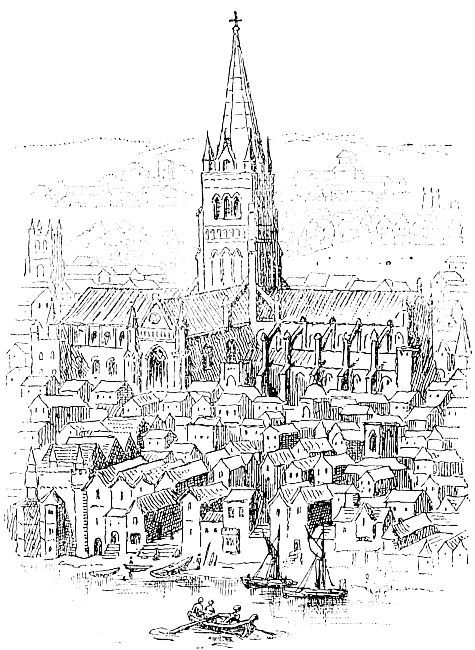

“(Sept. 7) At my return I was infinitely concerned to find that goodly Church (cathedral), St. Paul’s, now a sad ruin. It was astonishing to see what immense stones the heat had in a manner calcined, so that all the ornaments, columns, friezes, capitals, and projectures of massie Portland stone flew off, even to the very roof, where a sheet of lead covering a great space (no less than six acres by measure) was totally melted; the ruins of the vaulted roof falling broke into St. Faith’s, which being filled with the magazines of books belonging to the Stationers, and carried thither for safety, they were all consumed, burning for a week following.... Thus lay in ashes that most venerable Church, one of the most ancient pieces of [189]

[190]early piety in the Christian world, besides near 100 more. The exquisitely wrought Mercers’ Chapel, the sumptuous Exchange, the august fabric of Christchurch, all the rest of the Companies’ Halls, splendid buildings, arches, entries, all in dust.…

OLD ST. PAUL’S (A.D. 1500).

“The people who now walked about the ruins appeared like men in some dismal desert or rather in some great city laid waste by a cruel enemy....The by-lanes and narrower streets were quite filled up with rubbish, nor could one have possibly known where he was, but by the ruins of some Church or Hall, that had some remarkable tower or pinnacle remaining....”

Just as the Plague was by no means the first plague which had visited the city, so there had been other serious outbreaks of fire, but those two visitations were by far the worst in the history of London. We can gather some idea of the scene of desolation which resulted when we read that the ruins covered an area of 436 acres—387 acres, or five-sixths of the entire city within the walls and 73 acres without; that the Fire wiped out four city gates, one cathedral, eighty-nine parish churches, the Royal Exchange, Sion College, and all sorts of hospitals, schools, etc.

Yet gradually, not within three or four years, as is commonly stated in history books, but slowly, as the ruined citizens found money for the purpose, there rose from the débris another London—a London with broader, cleaner streets, with larger and better-built houses of stone and brick; with fine public buildings and a new Cathedral—a London more like the city which we know. So modern London began its life.

The River did not make a new London as it had made the old city. Shops, markets, quays, public buildings, did not spring up naturally in places where the trade of the time demanded them, as they had done in the old days, otherwise much would have changed. Instead, the new city very largely rebuilt itself on the foundations of the old, quite regardless of comfort or utility.

Its supremacy as a Port was never in doubt. With the tremendous break in London’s commerce, caused first by the Plague and then by the devastation of the Fire, it would have seemed possible for the shipping to decrease permanently; but it never did. So firmly was London Port established in the past that it lived on strongly into modern times, despite many excellent reasons why it should lose its great place.