CHAPTER NINE

The Riverside and its Palaces

TO-DAY, when we stand upon Waterloo Bridge and let our gaze rest upon the Embankment, as it sweeps round in the large arc of a circle from Blackfriars past Charing Cross to Westminster, it is hard indeed to picture the time when these massive buildings—hotels, public buildings, suites of offices, etc.—were not there, when the green grass grew right down to the water’s edge on the left strand or bank of the River, when a walk from the one city to the other was a walk through country lanes and fields. It is hard indeed to brush away all the ugly, grey reminders of the present, and see a little of the past in its beauty—for beautiful the River undoubtedly was in Plantagenet, Tudor, and Stuart times.

We have spoken of the growth of the city, and what the River meant to it; of the wharves and warehouses which extended from the Tower to the Fleet River. That was the commercial London of those days. Westwards from the Fleet, along the side of the Thames, spread the more picturesque signs of London’s prosperity—the dwellings of some of the wealthy and influential.

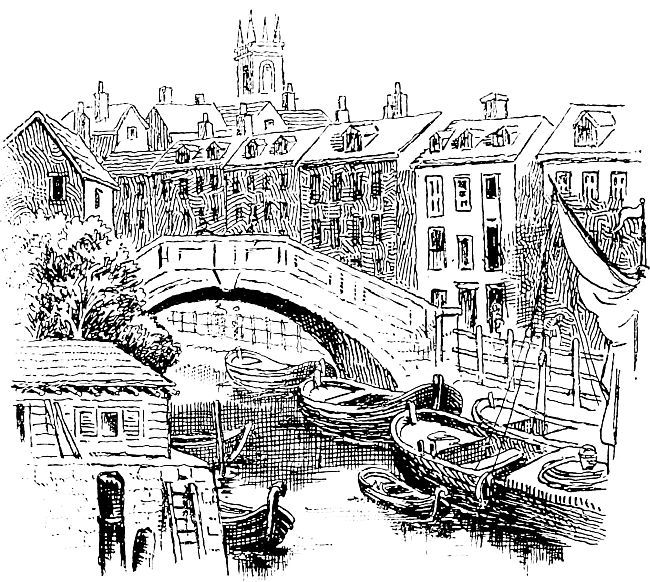

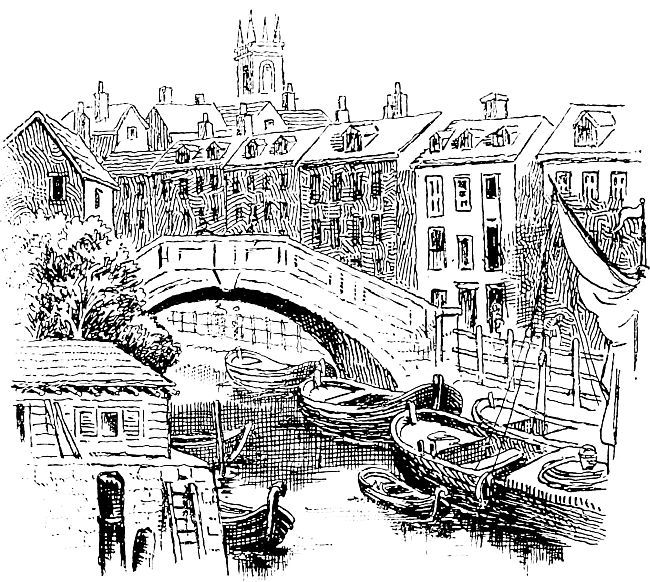

THE FLEET RIVER AT BLACKFRIARS (A.D. 1760).

From the western end of the city—Ludgate and Newgate—spread out westwards the suburbs, part of the city, though not actually within its walls, until an outer limit was reached at Temple Bar, situated at the western extremity of one of London’s most famous thoroughfares, Fleet Street, named after the little river which flowed down where Farringdon and New Bridge Streets are, and which emptied itself, and still empties itself, in the shape of a main drain, into the Thames beneath Blackfriars Bridge.

Between Fleet Street and the River stood the Convent of the White Friars, and that most famous of places the Temple.

In the Middle Ages the Church was far more intimately concerned with the everyday life of the people than it is to-day, for the simple reason that the clergy attended to the care of the sick and aged, to the teaching of the young, and other charitable works. Now it must be understood that there were in this country two classes of clergy—the monks, who were known as “regular clergy” (who lived by a regulus or rule), and the ordinary clergy, much as we have them to-day, in charge of our cathedrals, parish churches, etc., these last being known as “secular clergy.” For the upkeep of the Church folk paid what were known as “tithes.” To begin with, this “tithe,” or tax, was handed over to the bishop, who divided it out into four parts—one for the building itself, one for the poor, one for the priest, and one for himself. Gradually, however, the “regulars” obtained control of affairs, receiving the tithes, and, instead of giving the full quarters to the “seculars,” they simply paid them what they thought fit, and appropriated the remainder for themselves. This led to two things: the monasteries became enormously wealthy, and the seculars became exceedingly poor and dissatisfied; so that there was constant strife between the two branches. Many nobles, ignorant of the true condition of affairs, and wishing the excellent charitable work of the Church to be continued, made great gifts to the Church. Unfortunately these very great gifts were sometimes apt to do the very opposite to what their donors intended. Instead of the monks devoting themselves more and more earnestly to the care of the needy, they began to think more of their own comfort and position. They erected for themselves extensive and comfortable dwellings, with their own breweries, mills, and farms, and they lived on the fat of the land. They indulged themselves until their luxury became a byword with the common people. Then arose two great teachers, St. Francis of Assisi and St. Dominic, who were led to protest against the abuses. They founded new Orders of religious men—called the Friars—who went from place to place with no money and only such clothes as covered them. These men believed in and taught the blessedness of poverty.

Many of them came over from the Continent and settled in various parts of the city. If you pick up a map of London, even one of to-day, you will see such names as Blackfriars, Whitefriars, Crutched Friars, Austin Friars—showing where they made their homes. Some, the Black Friars, took up a position and eventually built for themselves a fine monastery and church just outside the city walls at the mouth of the Fleet River. Others, the White Friars or Carmelite Monks, made themselves secure just to the west of the Fleet.

Whitefriars was one of London’s sanctuaries; within its precincts wrong-doers were safe from the arm of the Law. Now, in certain periods of our history, such things as sanctuaries were good; they frequently prevented innocent men and women suffering at the hands of tyrants and unscrupulous enemies. So that the right of sanctuary was always most jealously guarded. But, as time went on, this led to abuses, and when the monasteries were closed by Henry VIII., the Lord Mayor of London asked the King to abolish the sanctuary rights of Blackfriars; but he would not do so. The consequence was that Blackfriars and Whitefriars, particularly the latter, became sinks of iniquity. In the latter, which was nicknamed Alsatia, congregated criminals of all sorts—thieves, coiners, forgers, debtors, cut-throats, burglars—as we can read in Scott’s novel, “The Fortunes of Nigel.” For years it held its evil associations, but it became so bad that in 1697 there was passed a Bill abolishing for ever the sanctuary rights of Whitefriars.

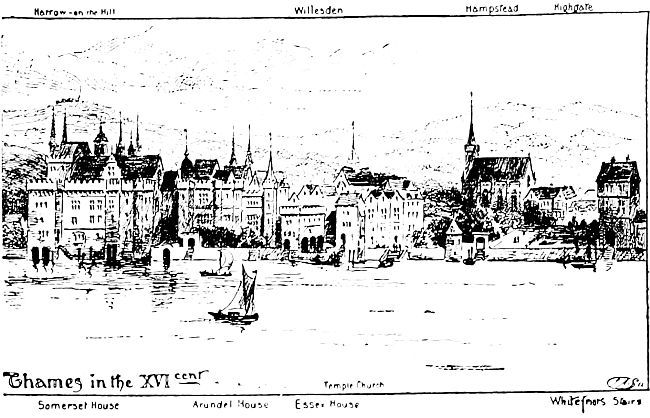

West of Whitefriars is the Temple, which, with its quiet old courtyards, its beautiful church, and its restful gardens stretching down to the Embankment, is one of London’s most fascinating places.

It gets its name from its founders, the Knights Templars—a great Order of men who lived in the time of the Crusades, and whose white mantles with a red cross have been famous ever since. These knights, who took vows to remain unmarried and poor, set themselves the great task of guarding the pilgrims’ roads to the Holy Land.

In 1184 the Red Cross Knights settled on the banks of the River Thames, and made their home there in what was called the New Temple. For 130 years they abode there, gradually increasing in wealth and power, till in the end their very strength defeated them. Princes and nobles who had given them great gifts of money for their worthy work saw that money used, not for charitable purposes, but to keep up the pomp and luxury of the place, and soon various folk in high places coveted the Templars’ wealth and power, and determined to defeat them.

So well did these folk work that in 1313 the Order was broken up, and the property came into the King’s hands. A few years later the Temple was leased by the Crown to those men who were studying the Law in London, and in their hands it has been ever since, becoming their own property in the reign of King James I.

Originally the Temple was divided into three parts—the Inner Temple, the Outer Temple, and the Middle Temple. The Outer Temple, which stood west of Temple Bar, and therefore outside the city, was pulled down years ago, and now only the two remain.

Here in their chambers congregate the barristers who conduct the cases in the Law Courts just across the road; and here are still to be found the students, all of whom must spend a certain time in the Temple (or in one of the other Inns of Court—Gray’s Inn or Lincoln’s Inn) before being allowed to practise as a barrister.

OLD TEMPLE BAR, FLEET STREET (NOW AT THEOBALD’S PARK).

The Temple Church, which belongs to both Inns of Court, is one of the few pieces of Norman architecture which survive to us in London. It is round in shape, now a rare thing. On the floor, and in many other places, may be seen the Templars’ emblem—the red cross on a white ground with the Paschal Lamb in the centre. Figures of departed knights keep watch over this strange church, their legs crossed to signify (so it is said) that they had fought in one or other of the Crusades.

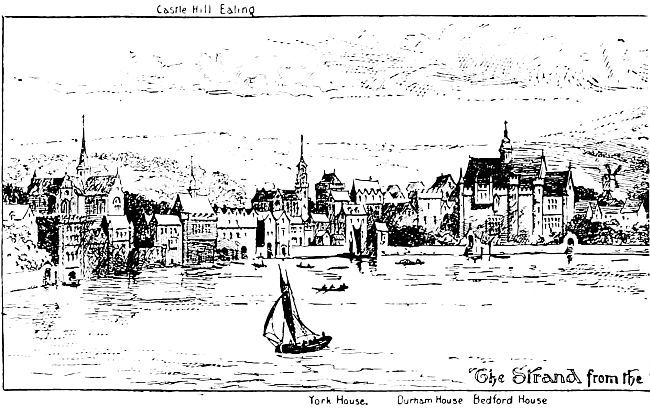

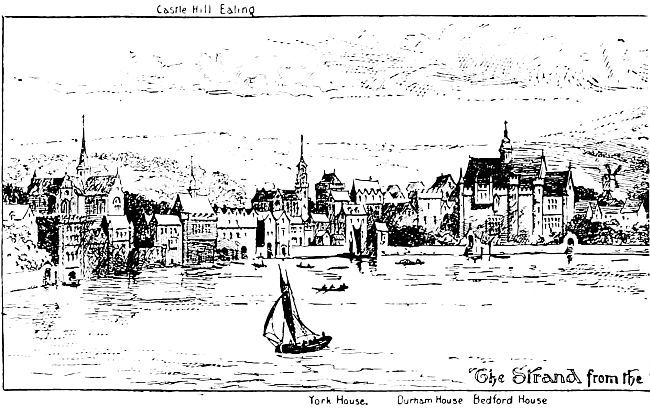

The Strand from the …

Castle Hill. Ealing. York House. Durham House. Bedford House.

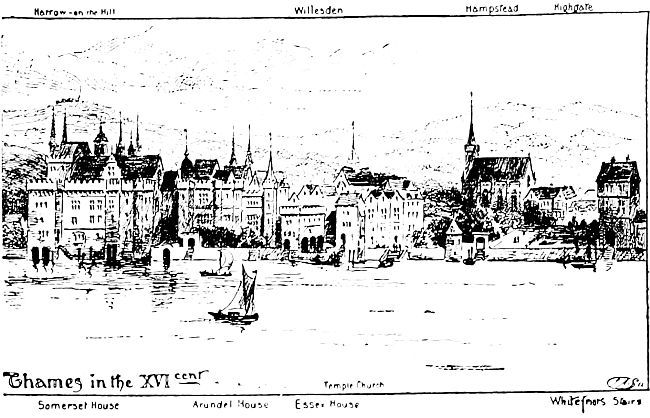

... Thames in the XVIcent

Temple Church. Somerset House. Arundel House. Essex House.

Whitefriars Stairs.

The Temple Gardens, which still run down to the Embankment, were one time famous for their roses, and, according to Shakespeare, were the scene of that famous argument which led to the bitter struggle known as the War of the Roses. You probably remember the famous passage, ending with the lines—

“And here I prophesy—this brawl to-day,

Grown to this faction in the Temple Garden,

Shall send between the red rose and the white

A thousand souls to death and deadly night.”

First Part of King Henry VI., Act II. Sc. 4.

Westwards from the Temple as far as Westminster stretched a practically unbroken line of palaces, each standing in beautiful grounds which sloped down in terraces to the water’s edge. There was Somerset House, which for long was a Royal residence. Lord Protector Somerset began the building of it in 1549, pulling down a large part of St. Paul’s cloisters and also the churches of St. John’s, Clerkenwell, and St. Mary’s le Strand to provide the materials for his builders; but long before its completion Somerset was executed for treason, and the property went to the Crown.

Here Elizabeth lived occasionally while her sister Mary was reigning. The old palace was pulled down in 1756, and the present fine building erected on the site. This modern structure, with its fine river front, so well combines strength and elegance that it seems a pity it does not stand clear of other buildings.

The rest of the palaces, westwards, survive for the most part only as names. Where now rises the great mass of the Savoy Hotel once stood the ancient Palace of the Savoy, rising, like some of the city houses, straight out of the River, with a splendid water-gate in the centre. It was the oldest of the Strand palaces, being built by Peter of Savoy as early as 1245. After various ownerships, it passed into the hands of John of Gaunt, and was his when it was plundered and almost entirely burnt down by the followers of Wat Tyler in 1381. From that time onwards it had a chequered existence, being in turn prison and hospital, till at last in 1805 it was swept away when the approach to Waterloo Bridge was made. There is still in the street leading down to the Embankment the tiny Chapel Royal of the Savoy, but it has been too often restored to have much more interest than a name.

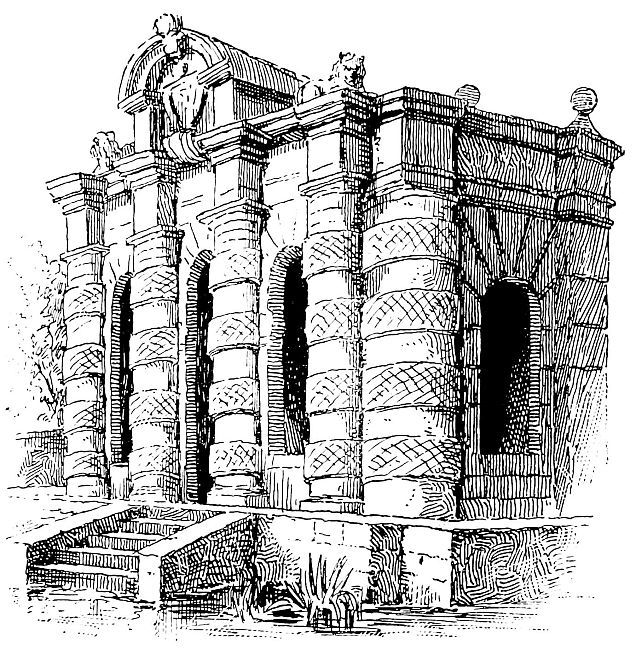

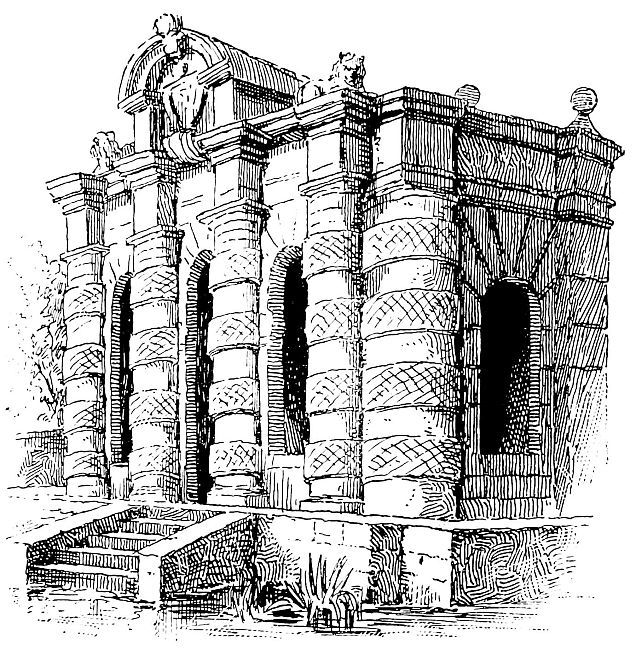

Where now comes the Cecil Hotel stood originally the famous palace or inn of the Cecils, the Earls of Salisbury. York House, the town palace of the Archbishops of York, stood where now is Charing Cross Station. This at one time belonged to the famous Steenie, Duke of Buckingham and favourite of James I. Buckingham pulled down the old house in order that another and more glorious might rise in its place; but this was never done. Only the water-gate was built, and this lovely relic still stands in the Embankment Gardens, and from its position, some distance behind the river-wall, shows us how skilful engineers have saved quite a wide strip of the foreshore.

In all probability each of these Strand palaces had its water-gate, from which the nobles and their ladies set out in their gay barges when about to attend the Court at Westminster or go shopping in London.

THE WATER-GATE OF YORK HOUSE.

Just beyond York House came Hungerford House, which has given its name to the railway bridge crossing from the station; and then came Northumberland House, which was the last of the great historic riverside palaces to be demolished, being pulled down in comparatively modern times to make way for Northumberland Avenue. Other famous palaces are remembered in the names of Durham Street and Scotland Yard.

When in 1529 Wolsey fell from his high estate, Henry VIII., his unscrupulous master, at once took possession of his palace at Whitehall, and made it the principal Royal residence. To give it suitable surroundings he formed (for his own sport and pleasure) the park which we now call St. James’s Park. When later he dissolved the monasteries he seized a small hospital, known as St. James-in-the-Fields, standing on the far side of the estate, and converted it into a hunting lodge. This afterwards became the famous Palace of St. James’s.

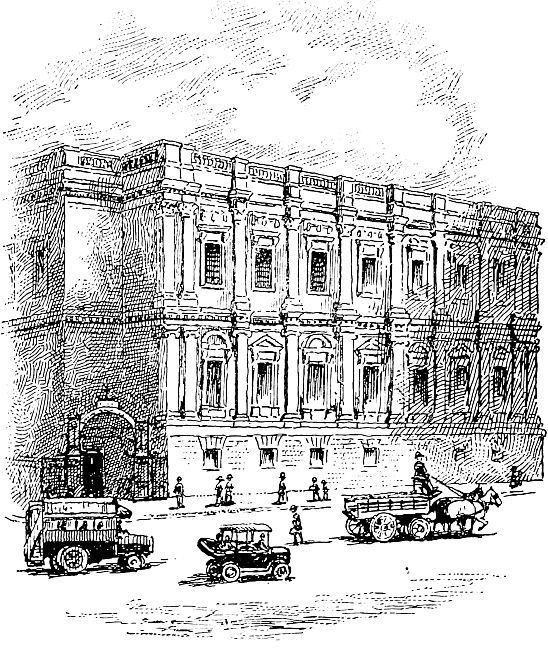

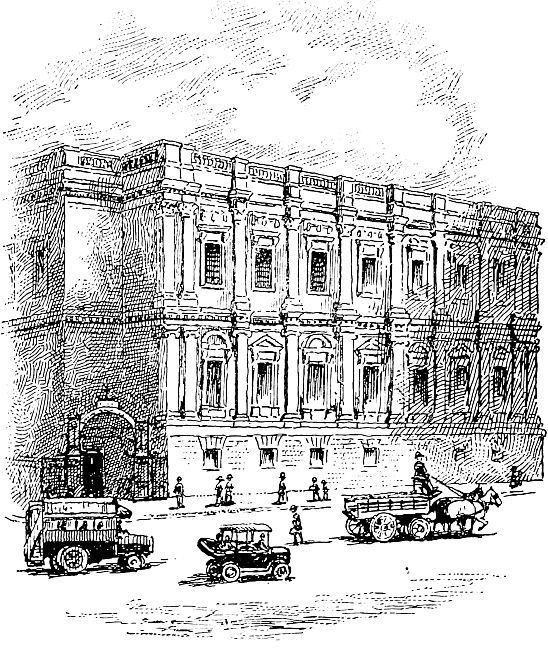

Of Whitehall Palace all that now remains is the Banqueting Hall (now used to house the exhibits of the United Service Institution), built in the reign of James I. by the famous architect Inigo Jones; the rest perished by fire soon after the revolution of 1688. For some time afterwards St. James’s Palace was the only Royal residence in London, but the Sovereigns soon provided themselves with the famous Kensington and Buckingham Palaces.

THE BANQUETING HALL, WHITEHALL PALACE.