CHAPTER TEN

Royal Westminster—The Abbey

THE story of Westminster is nearly as old as that of London itself.

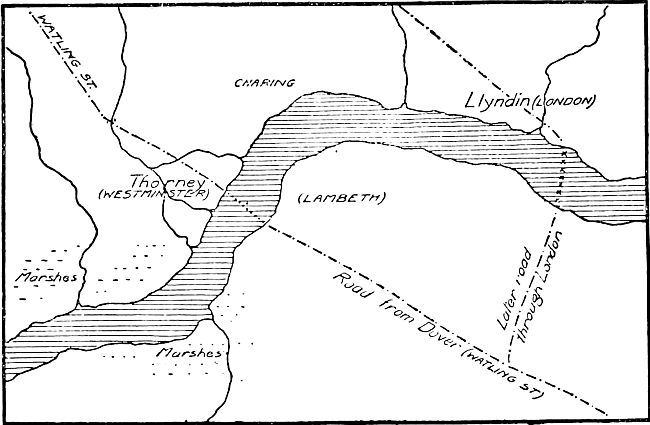

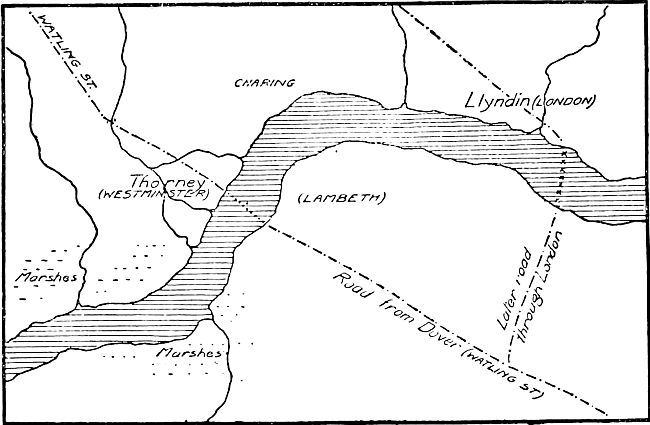

In our first chapter we spoke of the position of London being fixed to a large extent by the Kent road passing from Dover to the Midlands. That road, heading from Rochester, originally passed over—and still passes over—the Darent at Dartford, the Cray at Crayford, the Ravensbourne at Deptford; and then made its way, not to the crossing at Billingsgate, but to a still older ford or ferry which existed in very early days at the spot where Westminster now stands. If you look at the map of London, you will see that the Edgware Road, passing in a south-easterly direction from St. Albans, comes down, with but a slight curve, as if to meet this north-westerly Kent road. That they did so meet there is but little doubt, and this meeting gave us the Royal City of Westminster.

THE RIVER AT THORNEY ISLAND.

In pre-Roman days Lambeth and Westminster, Belgravia and Chelsea, were simply reedy marshes. Out of them rose a number of gravelly islands of various sizes, and one of these, larger and more solid than the rest—Thorney or Bramble Island—became in due course the site of the city which for centuries was second only to London itself; for though the building of the Bridge and the rapid growth of the Port meant the diversion of the Kentish Watling Street to a new route through London, the Thorney Island settlement grew just as steadily as that of the bluff lower down the stream, till eventually it held England’s most celebrated Abbey and Royal Palace, and its Houses of Parliament.

As so often happened in early days, the settlement developed round a religious house. Probably it originated in a British fortress. Certainly it comprised a considerable Roman station and market. But all that lies in the misty past. The legend remains that in the year 604 Sebert, King of the East Saxons, there founded a minster of the west (St. Peter’s) to rival the minster of the east (St. Paul’s) which was being erected within the City of London; and indeed we are still shown in the Abbey the tomb of this traditional founder.

When we come to the reign of Edward the Confessor we begin to get to actual definite things. Edward, as we know from our history books, was a very religious man, almost as much a monk as a King; and he took special delight in rebuilding ruined churches. While he was in exile in Normandy he made a vow to St. Peter that he would go on pilgrimage to Rome if ever he came into his kingdom. When, in the passage of time, he became King, and proposed to carry out his vows, his counsellors would not hear of such a journey; and, in the end, the Pope of Rome released him from his vow on condition that he agreed to build an Abbey to the glory of St. Peter.

This Edward did. His own particular friend, Edwin, presided over the small monastery of Thorney, so Edward determined to make this the site of his new Abbey. Pulling down the old place, he devoted a tenth part of his income to the raising of the new “Collegiate Church of St. Peter of Westminster.” Commenced in the year 1049, it became the King’s life-work, and was consecrated only eight days before his death.

In order that he might see the builders at work on his favourite project, he built himself a palace between the Abbey and the River, and for fifteen years he watched the rising into being of such an Abbey as England had never known. He endowed it lavishly with estates, and gave it the right of sanctuary, whereby all men should be safe within its walls.

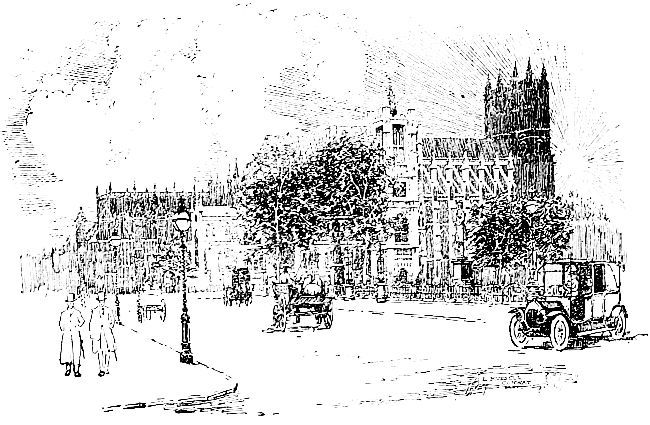

Of course, the fine structure we see as we stand in the open space known as Broad Sanctuary is not the Confessor’s building. Of that, all that now remains is the Chapel of the Pyx, the great schoolroom of Westminster School, which was the old monks’ dormitory, and portions of the walls of the south cloister. The rest has been added from time to time by the various Sovereigns. Henry III., in 1245, pulled down large portions of the old structure, and erected a beautiful chapel to contain the remains of the Abbey’s founder, and this chapel we can visit to-day. In it lies the sainted Confessor, borne thither on the shoulders of the Plantagenet nobles whose humbler tombs surround the shrine; also his Queen, Eleanor; Edward III., and that Queen who saved the lives of the burghers of Calais; also the luckless Richard II.

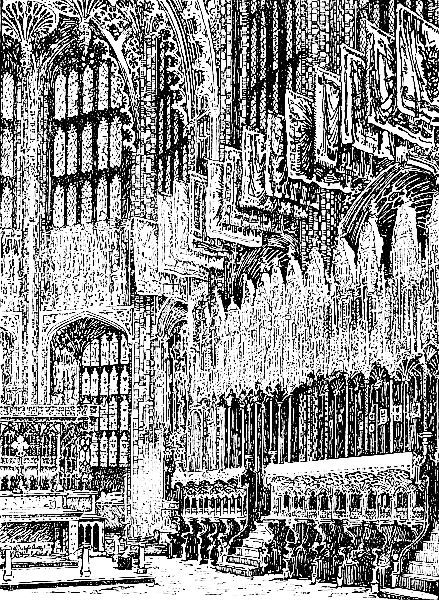

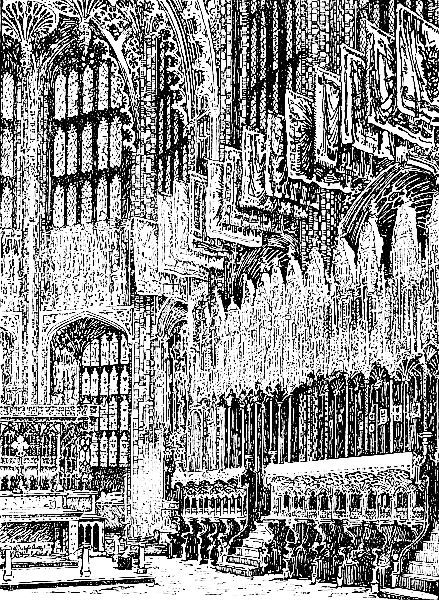

HENRY VII.’S CHAPEL, WESTMINSTER ABBEY.

Other Sovereigns also took a share; but it was left to Henry VII. to give us the body of the Abbey mainly in the shape we know. At enormous expense he erected the famous Perpendicular chapel, called by his name—one of the most beautiful and magnificent chapels in the whole world.

When we stand in the subdued light in this exquisite building, and examine the beautifully fretted stone-work of its amazing roof—a “dream in stone,” its “walls wrought into universal ornament,” the richly carved, dark-oak stalls of the Knights of the Bath with the banners of their Order drooping overhead—we find it hard to recall that this miserly man was one of the least popular of England’s Kings.

In this spot lie, in addition to the remains of Henry himself, those of most of our later Kings and Queens. Here side by side the sisters Mary and Elizabeth “are at one; the daughter of Catherine of Aragon and the daughter of Anne Boleyn repose in peace at last.” Here, too, rests that tragic figure of history, Mary Queen of Scots; and James I., Charles I., William III., Queen Anne, and George II.

For numbers of us one of the most interesting parts of the Abbey will always be “Poets’ Corner,” in the south transept. Here rest all that remains of many of our mightiest wielders of the pen, from Chaucer, the father of English poetry, down to Tennyson and Browning. Many of the names on the monuments which cluster so closely together are forgotten now, just as their works are never read; but the tablets to the memory of Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Dryden, Dickens, Tennyson, and Browning, will always serve to remind us of the mighty dead. The north transept is devoted largely to the monuments to our great statesmen and our great warriors.

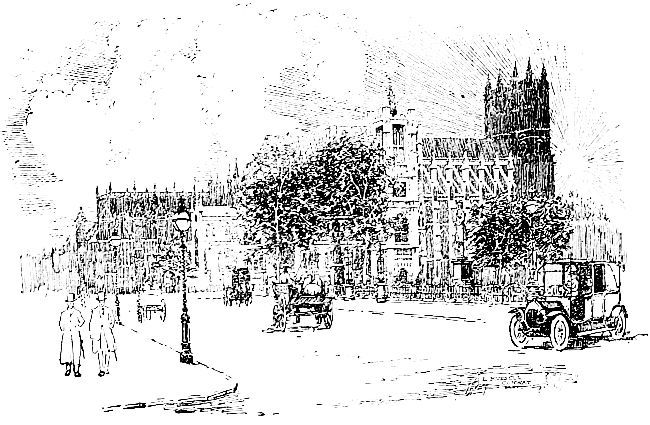

WESTMINSTER ABBEY.

In the Choir we come upon the Coronation Chairs. The Confessor in building his church had in mind that the Abbey should be the place of coronation of England’s Sovereigns; and down through the centuries this custom has been observed. Indeed, certain parts of the regalia worn by the King or Queen on Coronation Day are actually the identical articles presented to the Abbey by Edward himself. The old and battered chair is that of Edward I., the “hammer of the Scots,” who lies buried with his fellow Plantagenets in the Confessor’s Chapel. Just under the seat of the chair is the famous “stone of destiny,” brought from Scone by Edward, to mark the completeness of the defeat. Its removal to Westminster sorely troubled our northern neighbours, for they believed that the Supreme Power travelled with that stone. Since those days every English Sovereign has been crowned in this chair. Its companion was made for Mary, wife of William III.

In the Nave lies one of the most frequently visited of all the tombs—the last resting-place of the Unknown Warrior, who, brought over from France and buried with all the grandeur and solemnity of a Royal funeral, typifies for us the thousands of brave lads who made the great sacrifice—who died that we might live.

What most of us forget is that the place which we call Westminster Abbey was only the Chapel belonging to the Abbey, the place where the monks worshipped. In addition there was a whole collection of buildings where the monks ate, slept, studied, worked, etc. Of these most have been swept away. If we pass out through the door of the South Aisle we can see the ancient cloisters where the monks washed themselves, took their exercise and such little recreation as they were allowed, and where they buried their brothers. There was also the Abbot’s House, which afterwards became the Deanery, and there was the Chapter House, a building which fortunately has been preserved to us almost in its original condition. This was the place where the business of the Abbey was conducted, where the monks came together each day after Matins in order that the tasks of the day might be allotted and God’s blessing asked, where afterwards offenders were tried and penances imposed. Till the end of the reign of Henry VIII. the House of Commons met in this chamber when the monks were not using it; and afterwards it was set aside as an office for the keeping of records. When in 1540 came the dissolution of the Abbey, the Chapter House became Royal property, and that is why we now see a policeman in charge of it instead of one of the Abbey vergers.