CHAPTER IV.

PONSEE CAMP.

Desertion of the muleteers—Our encampment—Visit of hill chiefs—Sala’s demands—A mountain excursion—Messengers from Momien—Shans refuse presents—Stoppage of supplies—Ill-feeling—Tsawbwa of Seray—St. Patrick’s Day—Retreat of Sala—The pawmines of Ponsee—A burial-ground—Visit to the Tapeng—The silver mines—Approach of the rains—Hostility of Ponsee—Threatened attack—Reconciliation—A false start—Letters from Momien—A hailstorm—Circular to the members of the mission—Beads and belles—Friendly relations with Kakhyens—Their importance.

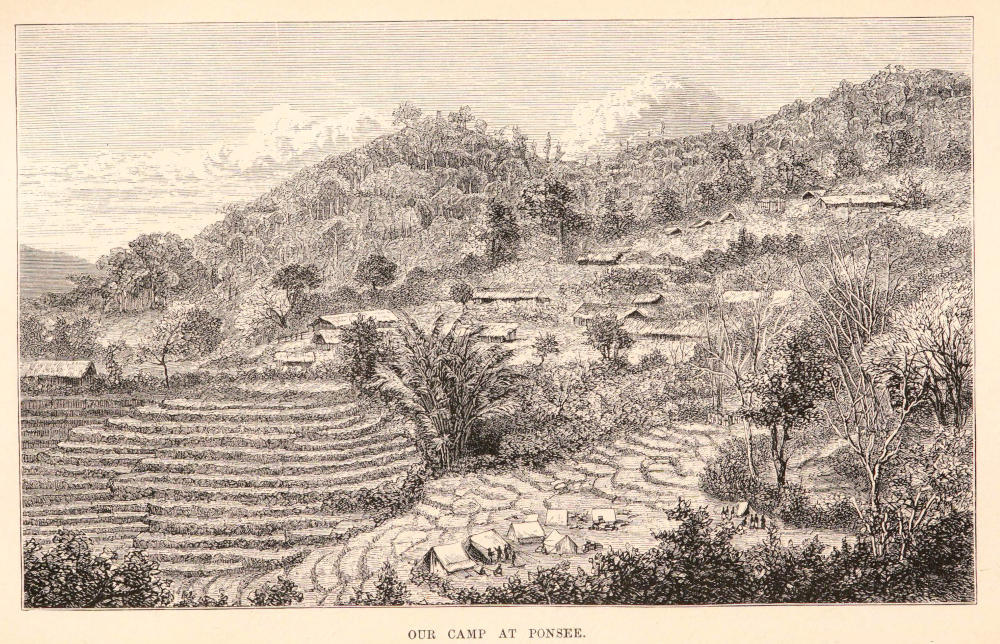

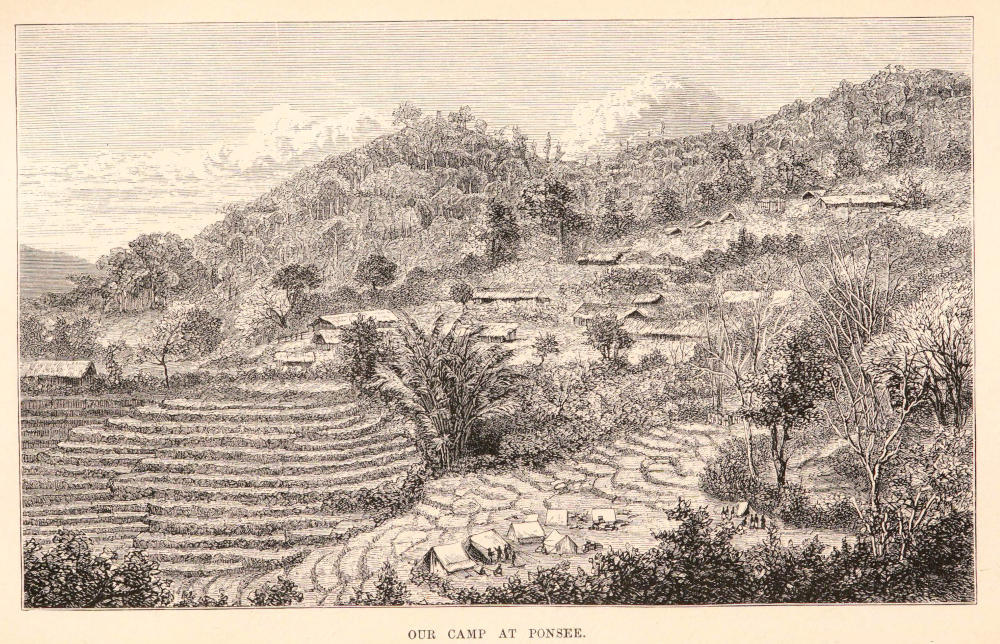

On the first night of our sojourn at Ponsee, we were roused from our beds in the open air by a violent thunderstorm, which threatened a drenching, but fortunately let us off with only a few heavy drops. One of the party drew his bed under a small thatched shed close by, and slept soundly, to awake in the morning and find that he had shared his shelter with a deceased Kakhyen, on whose grave he had been reposing. At an early hour, Sala came to inform Sladen that a small army of Shans and Kakhyens had collected to oppose our progress, but that two thousand rupees might purchase their goodwill. When informed that the disposable funds would not admit of such costly travelling, he significantly remarked that the Panthays were rich, and would be glad to assist us. This obstacle might be imaginary, but a most real difficulty left us no time to reflect on it, for instead of preparing for a start, the muleteers, without a word of complaint, or indeed any communication with us, proceeded to unpack their loads, flinging all the baggage on the ground. I went to look after my boxes, but was warned off by a Kakhyen, who flourished his dah, and worked himself up into such a fury that retreat appeared the wisest course. In a short time the mules and drivers marched away, taking the road to Manwyne, leaving us and our baggage destitute of any means of transit. A few beasts remained, belonging to Ponline, but too few to be taken into account. Here was an unexpected dilemma, such as would have delighted Sir Samuel Baker, who says he “finds pleasure in a downright fix.” Sladen set off to find out, if possible, the meaning of it all from Sala, who was seated comfortably drunk in the chief’s house. He declared that the muleteers had been influenced by messages from the Shan tsawbwas of Sanda and Muangla, threatening them with death if they brought us on. He advised threats of exclusion of the Shans from the Burmese fairs by way of reprisals, but Sladen indignantly told him that he came to promote peace, and not dissension, and that he would write conciliatory letters, explaining the object of the expedition to those chiefs who had been misled. Thereupon Sala grew confidential, and let out what certainly seemed the truth, in vino veritas, about our missing interpreter Moung Shuay Yah, who had been last seen or heard of at Ponline. It appeared that this half Chinese scoundrel had finally endeavoured to persuade Sala, and on his refusal the Talone tsawbwa, to murder Sladen and plunder the cash-chest. Thwarted in his villainous projects, he had returned to Bhamô, of which latter fact confirmation was afforded a few days later. Matters looked unpromising; it was whispered that the muleteers had become aware that our detention at Ponsee was certain, and were unwilling to hazard a delay, the profits of which would go into the greedy pockets of the Ponline chief. Besides the dark aspect of affairs, the natural atmosphere was overcast, heavy clouds presaging storm, and to be prepared against all consequences, we removed our quarters to the plateau vacated by the muleteers, where the three sepoy palls, or small tents, accommodated the Europeans, while the sepoys and followers set to work to construct bamboo tents, thatched with leaves and grass for their protection, and speedily a regular camp was established in a favourable position. Sala showed himself in a new light, later on in the day, when he came down very drunk, and dressed in a yellow silk cloth which he had stolen from Sladen’s servant. He was at first inconveniently affectionate, and, seizing Sladen by both hands, vowed eternal friendship; he then grew inquisitive about our rifles and revolvers, and required Sladen to show his marksmanship by splitting a bamboo forty yards off. A refusal to gratify him changed him at once into a violent savage, pouring out a flood of the foulest abuse in Burmese. With tact and patience, he was restrained from violence, but the real treacherous nature of the animal had shown itself unmistakably. He finally assured Sladen that he might make up his mind not to quit Ponsee until he had paid two bushels of rupees. More agreeable visitors arrived, in the persons of the Kakhyen chiefs of Nyoungen, Wacheoon, and Ponwah, small hill districts on the road to Manwyne. These tsawbwas all brought presents of fowls and rice, for which they received cloth as a return. The chief of Ponwah was a wiry little highlander, with oblique eyes, and strongly marked features of a Tartar type, adorned with two scanty tufts by way of moustache, and a sparse beard carefully restricted to the front of his chin. His dress was different from that of the other tsawbwas, and argued a higher social condition. It consisted of a blue turban, blue padded woollen jacket, a kilt of the same material and colour, with a red and blue border, finished off with richly embroidered leggings, and short blue woollen hose with thick soles. A leopard’s fang adorned his dah, and a cloth bag contained his metal pipe and bamboo flask of samshu, which frequently found its way to his thirsty lips; before each draught he dipped his finger into the liquor, and poured a few drops on the ground as a libation to the earth nats. The mother of the young Ponsee tsawbwa also came down, attended by a number of girls, bringing sheroo, or beer, cooked rice, eggs, and vegetables. Beads were distributed, but they begged for rupees; and a few four-anna pieces hardly contented them. One of us gallantly presented an importunate damsel with a pretty little bottle of perfume, and to make her appreciate it, poured a little on her hand, and signed to her to rub it on her face, but having done so, she evinced her disgust by wry faces, spitting at and abusing the donor, as though he had insulted her, to his extreme confusion.

OUR CAMP AT PONSEE.

The day of anxiety was followed by a night of rain and storm. Heavy gusts of wind, sweeping down the lofty shoulder of the mountain, threatened to carry away the light tents, and it required all our efforts to prevent this catastrophe by holding stoutly on to the tent poles. The interior was of course inundated, and beds and bedding saturated with water, but some of the followers were worse off, having no shelter of any sort. Our troubles, however, were only beginning. The Nanlyaw tamone,[21] who had been ordered to accompany us as interpreter, and had failed to do so, arrived with orders from the Woon of Bhamô to the tsawbwas of Ponsee and Ponline to repair at once to Bhamô, and assist in an inquiry about reopening the silver mines. The message and the messenger were both suspicious, and some obstructive influence speedily showed itself. A demand was set up for three hundred rupees, compensation for five houses said to have been destroyed by a jungle fire, originating in the embers of our camp-fire at Lakong. Sala evidently thought that any demands would be complied with to prevent his deserting us, and talked much about the imperative orders of the governor. By way of relief from the discussion, we made an excursion up the mountain to a height about six hundred feet above our camp, whence a splendid panorama unrolled itself of the Burmese plain as far as Bhamô, and the junction of the Tapeng with the majestic Irawady. We passed numerous oaks, and a grove of trees bearing nuts exactly like our own hazels. At the highest point reached, a Kakhyen village was found, snugly nestled in a beautifully cool hollow, with a small stream flowing down the hillside.

Our appearance startled three women, proceeding to fill the bamboos, which serve as water pitchers, carried in a wicker basket at the back; they darted into a hollow below the road, and, turning their backs to us, waited till we had passed by. A thousand feet below us, a deep ravine resounded with the cry of hoolock monkeys, howling at the full pitch of their voices. Shooting, either for sport or purposes of science, was rendered extremely difficult by the dense jungle and the steep sides of the deep gorges, where the birds are mostly found, for a bird, when shot, dropped down a steep declivity, into long grass or tangled shrub, where search was useless.

On our return, a cock and hen partridge, of a new species, belonging to the genus Bambusicola, were shot in the cleared ground, and in the woods the cry of an oriole was often heard, but the birds were invisible. Descending by another route, passing the rice clearings, where wild strawberries carpeted the ground with flowers and fruit, and two sorts of violets and various brambles were also in flower, we reached the camp, and were soon plunged again into debate with Sala. The fellow was sulky and angry, demanding six hundred rupees blackmail, and three hundred as compensation for the village fire, threatening as an alternative to leave us to “be lost in the hills and never more heard of.” Sladen temperately refused to submit to such extortionate demands, but, to prove his friendly intentions, offered to compensate for any actual damage, and to send presents to the chiefs en route. His arguments had such an effect on Sala that he was content to ask for one hundred rupees to settle the “fire.”

At this stage of the interview all were surprised by the sudden appearance on the scene of three strangers, dressed in gorgeous Chinese costume, and attended by half a dozen others; two of their faces were familiar, and they saluted Sladen with an air of recognition, but Sala and he were at first equally puzzled as to their identity. The two foremost were arrayed in blue satin skull-caps embroidered with gold, padded and embroidered jackets of fine blue cloth, and wide trousers of yellow silk. They wore new broad cane hats and gold embroidered Chinese shoes. The hilts of their dahs were each enriched with half the lower jaw of a leopard, and suspended from their button-holes was a decoration consisting of a pink and blue square of cloth, with a cipher embroidered in the corner. This was full dress Panthay uniform, which one of them proceeded to divest himself of, and exhibited his ragged Kakhyen garb underneath, and then Sladen recognised Lawloo, the scout despatched by him from Bhamô to the governor of Momien. He produced, carefully rolled up, a packet addressed in Arabic on a strip of red paper, which contained an envelope stamped with Chinese hieroglyphics in red, and a letter written in Arabic, and stamped with Chinese devices in red and blue; attached to this was another letter in Chinese. The latter no one could read, and a combined attempt made by the native doctor and the jemadar to decipher the former also failed, but Lawloo assured us that the governor of Momien was most friendly. He had received the messengers with all respect, and had equipped them in the gorgeous dresses which had disguised them from our recognition. He had also sent with them Shatoodoo, an officer in the Mahommedan service, a tall, fair-skinned, well-built man, dressed in blue uniform, with a fine intelligent face and the quiet self-possession of a well-bred gentleman. Our couriers, men belonging to the Cowlie tribe, bore their new honours with great composure; they completely ignored the presence of the Ponline tsawbwa, while they told of their kindly reception, and explained the purport of the letters. The governor had expected us by the “ambassadors’” route, which leads from Bhamô into Hotha, where he had arranged to meet us. They said we were not to advance at present via Manwyne, unless we were strong enough to fight our way past Mawphoo fort, the stronghold of Li-sieh-tai. The messengers, on their return, though conspicuous by their Panthay uniform, had travelled openly and unmolested through the Shan states, which had been declared to be hostile to our advance. The immediate effect was to cause Sala and the pawmines to withdraw from our tents, which was a great relief, as they had infested them, squatting on the beds for hours together, smoking, and chewing tobacco and betel, while any remonstrance was at once replied to with an angry scowl and a flourish of the naked dah. But the peace did not last long. The tsawbwa soon recommenced his demands, and day after day the fire question was discussed, and terms of settlement agreed upon, only to be insolently repudiated on the first occasion.

The next day more practical preparations for opening the route were made by the despatch of letters and presents to the Kakhyen chief of Seray, and to the Shan chiefs or headmen of Manwyne and Manhleo. Two of the Ponline pawmines and the interpreter Moung Mo, the tamone of Hentha village, whose services and goodwill we had secured, went in charge of the presents, and Sladen’s Burmese writer was also sent, by way of check on the pawmines. They returned in a few days with the presents, which the chiefs had declined to accept, as the tsawbwa of Sanda had refused his consent to our passage, and the Manwyne people, though favourably disposed, were afraid of the poogain, or headman, of Manhleo, a town situated on the south bank of the Tapeng, opposite Manwyne. This official was an inveterate enemy of the Panthays, and a few years before had massacred a Panthay caravan of peaceful merchants. The character and intentions of the expedition had been so misrepresented by the Chinese traders at Bhamô that the Shans were naturally indisposed to run any risks from our presence among them.

The refusal of the presents caused Sala to raise his demands; “all the people, Burmese, Chinese, and Shans,” he declared, were leagued against us, and if we did not secure his protection, we should have our heads cut off. This was his usual argument, illustrated by holding an imaginary head with his left hand, and making the motion of sawing at the supposed neck with his right.

A more practical result of the secret opposition was the stoppage of supplies. Soon after our arrival the Shans from the Manwyne district had discovered that there was a sure market for their provisions, and a regular bazaar had been established in our lines. Kakhyen villagers as well as Shans brought in fowls, rice, salt, vegetables, &c., and competition had kept prices down; empty beer bottles were found to be highly prized, and one bottle was worth twelve measures of rice. Among other things, the Manwyne Shans brought in sugar candy, and preserved milk in the form of thin cakes of paste like a film of coagulated cream, which placed in a cup of water over night supplied a cup of excellent milk in the morning. The method of preparation we could not learn, but the result was undeniably successful. The attendance of Shans, however, fell off, owing to the ill-usage received by many of them from the Kakhyens, who helped themselves to their goods, and paid them with abuse and blows. Hence supplies fell short, and prices rose accordingly, and it became unsafe moreover to wander for any distance from the camp. On one occasion one of us was tempted to indulge in a bath in the small stream which flowed immediately below. There was a most perfect douche, where the water leapt over a huge boulder, embowered in gigantic bamboos and splendid ferns, as though contrived for the secret bath of a Kakhyen sylvan nymph: but the unhappy European invader was scarcely in full enjoyment of the refreshing douche than he was saluted with a shower of stones and broken branches from some villagers who had watched him. This was a ludicrous side of popular hostility, but as the “fire” question continued to be discussed, almost daily warnings were brought to us that ill-disposed Kakhyens were collected on the heights above, intending to attack the camp under cover of night.

A slight change in affairs was effected by the arrival of the tsawbwa of Seray, a village four miles distant, who made his appearance on the 13th, attended by his pawmines and a numerous retinue. He was a rather short stout man of about forty-five, dressed in blue from turban to shoes; his manner was serious and respectful, and his remarks sensible, but evincing great curiosity about all the novelties that presented themselves. When he found leisure to discuss business matters, he asked us the particulars of the fire question, saying that if it were settled, he would undertake to guide us by a hill route to Momien, so as to avoid the necessity of passing through Sanda. Sladen explained to him that though the fire question had been settled three times, he would now submit it finally to his arbitration, and the demand, which had risen to five hundred rupees, was by his award satisfied by a promise of two hundred and sixty. Notwithstanding this settlement, that evening both the tsawbwas came down to request us to keep fires burning, and maintain a careful watch all night, as over a hundred men had collected on the hillside commanding the camp, intending to try their chance in a night attack, according to their usual tactics. Sala had endeavoured, he said, to dissuade them, and had finally told them he would look on while they were shot down by our men. The night, however, passed off more quietly than the days, which were occupied in ceaseless discussions; the question of mule hire being again in debate. Sala brought forward the preposterous demand of twenty rupees a piece for one hundred and sixty mules, those, namely, whose owners had deserted at this place. This demand was supported by fictitious tallies, and his disgust at finding we had kept an accurate account was great, while his fury at the laughter with which his attempts at extortion were met found vent in the usual pantomimic prophecy of our decapitation. The party of tsawbwas was increased by the arrival of the chief of Wacheoon, who brought a present of rice and sheroo; the object of his visit being to make the pertinent inquiry as to what still detained us at Ponsee.

On St. Patrick’s Day, matters came to a crisis. All the morning the tsawbwas and pawmines were assembled in our tent, arguing about the mule hire; even the respectable chief of Seray had caught the infection of covetousness, and demanded twenty rupees a mule for a journey of a few hours. The Seray chief was attended by a Chinaman who had been in his employment from his youth, and now acted as his chief trader. He had interpreted the Momien letters, and seemed to desire to be useful, but it was plain that he regarded the expedition as a military one, designed to assist the Panthays. He declared that the Sanda people were willing to receive us, but were restrained by fear of Li-sieh-tai. Sladen offered five hundred rupees, in addition to the money already paid, for sufficient carriage to Manwyne, where he would await the answer to his letters despatched the day before by the former messengers to Momien and to the tsawbwa of Sanda, as he was determined not to advance without the full consent of all the Shan chiefs. He then, by a happy thought, recounted to the assembled tsawbwas the sums of money and presents that the arch robber Sala had received from him for distribution. At this startling revelation, the chief of Ponsee was evidently exasperated, and a storm was brewing, when suddenly a shot was fired from a house on the hill above us, and a bullet, or slug, whizzed over the tent in which we were sitting, and presently another struck the head of a camp cot inside. All were naturally startled, but no one believed the first shot to have been intentionally aimed until the second was fired after the lapse of a few minutes. Sala and the pawmines sprang out, and vociferated frantically to the people in the village above. The chief of Seray sat silent, and presently announced that he should return to his own home, and the meeting was forthwith dissolved.

True to his word, the Seray chief departed the next day, leaving the message that he would return as soon as we were rid of Ponline; and the next news was that the Ponsee chief had threatened Sala with instant vengeance, and that our friend and protector had decamped to his own village, taking with him all the presents entrusted to him for the officials of Manwyne, &c., and forcibly carrying off our Burmese interpreter Moung Mo.

The tsawbwa and pawmines of Ponsee, who now came to the front, as self-appointed arbiters of our destinies, so far as progress was concerned, have not yet been introduced.

The tsawbwa was a youth of eighteen, who possessed no influence. What natural intelligence he might possess was obscured by his habits of continual intoxication and debauchery, in company with a number of “fast” young Kakhyens. He had hitherto preserved a sort of sullen neutrality, occasionally, however, conveying to us useful warnings, but acting neither for nor against us. The real power seemed to be exercised by his pawmines, four brothers who had generally shown themselves friendly. The eldest was a good-for-nothing merry-andrew, in a chronic state of intoxication. The next in age was a quiet, sensible man, who seemed fully to appreciate the advantages that would accrue to his people from the reopening of the trade between Yunnan and Burma, and he frequently declared that he was ready to give us all the help in his power. He was nicknamed by us the “Red Pawmine;” and his next brother and constant companion, a little spare man, with high cheek-bones, deeply sunken eyes, and features sharpened and worn by bad health, was appropriately styled “Death’s Head.” He was by far the ablest, but his quick, nervous temperament and violent temper rendered him a difficult man to deal with. The youngest, as excitable, but far less intelligent, was regarded with jealous eyes by his three elder brothers.

The young tsawbwa for about a week subsequent to Sala’s departure professed himself our friend, and a few days of tranquil and almost patient expectation ensued, during which we endeavoured to extend our acquaintance with the hill country about us, of which we had as yet been able to see no more than the outskirts of our camp or rather prison.

Accordingly, Stewart and I started on our ponies to ascend the mountain, taking Deen Mahomed as interpreter and a native boy to act as guide. No sooner had the party passed the tsawbwa’s house than a hue and cry was raised by one of the pawmines, who shouted orders to the lad to return at once. Disregarding the outcry, we pushed on along a narrow bridle-path, but were delayed by the obstinacy of a pony who declined to face a difficult bit of road, and the villagers overtaking us, the guide was dragged away by the pawmine. The tsawbwa was appealed to, but he declared that it was not safe to go up, as there was a village of “bad Kakhyens” on the mountain, and Deen Mahomed was warned with gesture symbolical of throat-cutting of what would happen to him if he got another guide. We consoled ourselves for this failure by a visit to a burial-ground, on the top of a thickly wooded height, which lay to the east of the camp. The path leading to it was sprinkled at intervals with ground rice, as an offering to the nats, and on two of the graves, which were quite recent, lay a little tobacco and a small cylindrical box containing chillies, while outside the surrounding trench the skull of a pig, with some more tobacco, had been placed. The conical roof of bamboos and grass was decorated with a finial of wood cut into two flag-like arms, painted with rosettes in black and red, which ridiculously resembled guide-posts.

The tsawbwa proved more obliging a day or two afterwards, when a request was sent to him for a guide to conduct us to the Tapeng river. The path led along the saddle of the long spurs running down to the valley, and the climate as we descended changed from temperate to tropical; the upper forest consisted of oaks, cherry, apple, and peach trees, especially in a magnificently wooded glen, while a large mountain stream made its way over a rocky channel, forming at one place a splendid waterfall over a perpendicular cliff of gneiss. Along the tops of the fruit trees a large troop of monkeys (Presbytis albocinereus) were leisurely wandering.

In descending we could only keep our footing by clutching at the overhanging branches, as our feet slipped on the fallen leaves and bamboo spathes which lay heaped in the steep and narrow path. The roots which projected every now and then were another and even worse impediment. Where, as often happened, the path turned a sharp angle on the crests of the precipitous spurs, great caution was needful, for if one had lost his equilibrium in such a place, he would have certainly sent all in front of him down the almost perpendicular declivity. As the lower level was reached, the trees became essentially tropical, intermixed with musæ, bamboos, ratans, and splendid ferns, while huge cable-like creepers intertwined their leafy cordage, and orchids of various and novel species displayed their fantastic beauties, and loaded the air with perfume.

After a long scramble down, we climbed over a secondary spur, and at its foot reached a sandy strand shaded by a magnificent banyan covered with the fragrant blossoms of a large yellow orchid (Dendrobium andersoni, Scott). Before us the roaring Tapeng rushed in a torrent forty yards wide, over a rocky bed, in a succession of foaming rapids and deep smooth reaches. At this point its bed was about thirteen to fourteen hundred feet above the plains at Tsitkaw, twenty miles distant, so that its descent is nearly seventy feet in the mile, the water mark indicating the highest rise of the flood to be twelve feet above its present level.

The only birds visible were two water wagtails flitting from boulder to boulder in the middle of the torrent. The rocks in position were gneiss, with veins and large embedded oblong pieces of quartzite; the quartz often standing out in bold relief where the gneiss surface had been worn away by the action of the water. Huge boulders of the same rock and pure white crystalline marble were strewn along the river bed. Along the bank a footpath led to a spot where a raft lay ready, in the deep smooth water above a rapid, to ferry over passengers to the silver mines. The raft was attached by a loop to a bark rope, stretched across the river. Our guide expressed his readiness “for a consideration” to conduct us across, but not “that day;” so we made our way back again, and if the descent had been difficult, it may be imagined how much more so was the return journey, which, however, was safely accomplished.

A few days after this trip, we started, accompanied by two of the Ponsee pawmines, for a visit to the silver mines. We reached the river by the next spur, to the west of the path followed on the former excursion, and, leaving the servants to prepare breakfast under the banyan tree, made for the raft. The guide rope was fastened to a fallen tree, six feet above the river on the opposite bank, while on our side it was carried over forked branches, firmly fixed in the ground and secured to a huge boulder. The raft proved to be on the other side, and one of the Burmese followers caught hold of the rope, and hand over hand succeeded in making his way across the strong current. He was followed by one of the pawmines, who evinced a careful dexterity which argued him to be well accustomed to what seemed a dangerous task. The raft was then brought across, one man in front running the loop along the rope, and the other sitting behind with a paddle to keep it stemming the stream. It was a simple wedge-shaped platform of bamboos lashed together, presenting a sort of prow which is kept against the rush of the stream. Bamboos at each side supported seats of split bamboo, and when the raft, which carried six persons, was loaded, the “deck” was a couple of inches under water.

Arrived at the other side, we were struck by the prevalence of white marble, and the extraordinary contorted folds of an abrupt cliff of blue crystalline quartzite rock, about fifty feet high, overlooking the ferry. A narrow footpath to the north-east of this cliff led to a ridge of pure white crystalline marble, of the same structure as the marble of the Tsagain hills. The ridge, which was destitute of trees, was about six hundred feet above the level of the river, running almost parallel with its course for about a mile. A small watercourse dividing the ridge from a rounded hill covered with waterworn boulders of the quartzite rock marked the limits of the marble, which terminated so abruptly as to be at once noticeable, and the pawmine said there was no silver beyond this limit. We walked along the almost level top of the treeless ridge, and found at the eastern side a pleasant valley, where the cultivated terraces showed signs of the neighbourhood of a village, and a Bauhinia in full bloom of white flowers with violet centre occurred in great profusion.

The mines consisted of a series of galleries about four feet in diameter, run horizontally into the slope of the ridge facing the river. Our conductors led us along the steep hillside, strewn with large masses of iron pyrites, and overgrown with grass and low jungle, so thick that each man had to cut his way with a dah. We passed about thirty of these adits, which penetrated the hillside for two or three hundred feet, sloping slightly downwards, and with passages opening at right angles. I crawled into one of them, preceded by a guide with a lantern, and made my way for a considerable distance along the tunnel, the sides of which showed red earth mixed with masses of marble and quartzite, but my progress was stopped by finding the passage blocked by the fallen roof, the bamboo props used when the mine was worked having given way. No detailed information regarding the productiveness of these mines could be obtained, and since the outbreak of the civil war in Yunnan they had not been worked, save to a very small and intermittent extent by the Kakhyens. The heaps of slag in the glen near the small watercourses, where all smelting operations had been conducted, showed that a very considerable quantity of ore used to be raised. Specimens of the ore assayed by Professor Oldham have been found to contain 0·191 per cent. of silver in the galena. The mines are of easy access, and from their close proximity to the borders of China, little or no difficulty would be experienced in finding labourers to work them. Silver is also said to be found on the right bank of the river, at a great elevation on the hillsides to the west of Ponsee; and gold is asserted to occur near the same locality, and specimens were shown to me at Bhamô in grains some of which were as large as small peas.

From the mines we returned across the river, and breakfasted on the bank of the Tapeng, treating our Kakhyen companions to some of the eatables, their approval of which was indicated by jerking their fists with the thumb extended, which emphatically signifies that anything is very good. The forefinger is held straight to indicate that a man is good, and crooked to denote one who is not to be trusted.

So we returned to Ponsee, where we must again take up the tangled thread of events bearing on our progress. A month had passed since our arrival, and the advance of the season was marked by the call of the cuckoo, which was often heard in the eastern woods. The jungle had all been felled in the new clearings, and nightly fires illuminated the opposite hills, caused by the burning of the jungle over acres of ground. Heavy thunder showers almost every night did not add to our comfort, and heralded the speedy setting in of the south-west monsoon.

But we were apparently as far off from any extrication from our detention as ever.

The Seray tsawbwa had on March 22nd returned with news that a Panthay official had arrived at Sanda, and that the country so far was open. He also produced a letter addressed to himself by the governor of Momien, requesting him to give us all the help in his power, and promising to reimburse any expense he might be put to in our service. The chief seemed fully disposed to help, and started for his own village to procure mules, with which he promised to return in two days, leaving his Chinese clerk to help us as an interpreter.

This was pleasant, and the improved temper of the people was shown by the arrival of messengers from the widow of a tsawbwa ruling a district on the road to Manwyne, with a present of fowls, eggs, and an uninviting compound of flour and chillies; accompanied by a message that she and her people would come and escort us to Manwyne. The dowager of the late chief of that town also sent Sladen the gift of two Kakhyen bags, and a curious implement forming a toothbrush and tongue-scraper combined.

The Seray chief, however, did not show according to promise, and a week after his departure news came that two Chinamen had arrived from Bhamô, with a party of fifty armed Burmese. These men gave out that they had been sent to recommence mining operations at the silver mines. The immediate result was that the Seray chief, first by a messenger, and then in person, repudiated his engagement to procure mules, alleging that the Ponsee chief had threatened to kill him if he assisted us to quit the Ponsee territory. Argument and expostulation were useless, and he nodded assent when Sladen attributed his change of purpose to private instructions received from Bhamô. He departed, after warning us to be on our guard against the Ponsee chief, who had resolved to attack the camp.

The hostility of the Ponsee chief was soon shown, for the day after the arrival of the Burmese his Kakhyens drove off all the Shans from our little bazaar; the chief himself came down with his dah drawn, and cut down one of the traders, which act of violence made him liable to pay an indemnity to the Manwyne people. His pawmines came next with the intelligence that he had summoned two neighbouring tsawbwas to his assistance, that two buffaloes had been slaughtered, and a grand sacrificial feast was to be held that night, after which the nats would be consulted as to our fate, when, if the oracle commended it, the Kakhyens, drunk with sheroo and samshu, would attack the camp. One of the buffaloes had been supplied by the Burmese, and the symbolic present of a pound of flesh, the acceptance of which signified consent, had been offered to and accepted by the tsare-daw-gyee, or Burmese royal secretary, in charge of the party. The pound of flesh had been also sent to the pawmines, but rejected by them, and they loudly denounced their chief as an uncontrollable madman.

A wholesome fear of the European strangers had gradually grown up; they were believed to possess supernatural powers. Breech-loading rifles and revolvers, and “Bryant and May’s matches,” which ignited only on the box, and defied wind and rain, argued a close alliance with the nats of the elements; while the photographic apparatus appeared in Kakhyen eyes to be the instruments of conjurers, who could control the sun himself. Hence but few of the Kakhyens would join the chief, whom they considered bent on his own destruction. While the conspirators were revelling and consulting, our police escort was drawn out and exercised, and the ominous sound of three volleys from fifty guns, which to their universal astonishment and awe all went off at once, terrified them, and gave a significant hint that assailants would meet a warm reception. The pawmines prayed that they and their houses might be spared in the general destruction that must overtake our enemies, and the news soon reached us that the meetway, who was secretly in our pay, had announced that the nats disapproved of the conspiracy.

The pawmines then requested permission to introduce the two hostile tsawbwas, who accordingly arrived; their naturally villainous faces were not improved by an expression of sheepish fear, but they lightened up when Sladen received them kindly, and without upbraiding them explained the advantages that would arise to all if our plans should be carried out. A present of an empty biscuit tin and a beer bottle quite won their hearts, and converted them into fast friends. The pawmines then represented that the young chief, with whom, on his repentance, they had made friends, desired to be forgiven and received into favour. It was argued that he felt very sore at Ponline having defrauded him of his rightful gains, and it was agreed that by way of making up for all neglect he should receive one hundred rupees! He swore eternal friendship, and vowed that henceforth we were his relations. Sladen asked him why he had omitted his relations in the late distribution of beef, at which he grinned, and went off awkwardly enough, but still in good humour.

During the first few days of April, the situation was hopeful and exciting, but the tsawbwa and his pawmines, though outwardly reconciled, soon made it evident that their respective interests clashed too much for united action. The chief volunteered to go and procure mules, the pawmines offered to supply any number of coolies. The amount to be paid on our arrival at Manwyne was fixed at five hundred rupees, and this was eagerly coveted by the rivals; each in turn denounced the other as entertaining designs of looting the baggage, and the pawmines declared that the chief dared not show his face in Manwyne on account of a private feud.

Sladen refused to accept the separate services of either the chief or his subordinates, and this straightforward policy compelled a seeming reconciliation. The Seray tsawbwa sent his pawmines with sixty men and six mules, far too few for the baggage of the party; his men, however, declared they could carry it all, and facetiously advised us to build houses for permanent residence at Ponsee, as the latter chief would never be able to procure mules.

An amusing interlude was afforded by the arrival of a half-caste, professing to be one of the chief men of the tsawbwa-gadaw, or dowager chieftainess, of Manwyne. He came in a breathless state of excitement, and announced that he had succeeded in hiring two hundred mules, but that the caravan had been detained by the Kakhyen chiefs on the road, who had sent him to say that they would allow them to pass for one hundred rupees, and as a pledge of their sincerity had entrusted him with an amber chain worth that sum. The fellow must have had a high opinion of our credulity, for the chain, when produced, was valued at about eight annas, and he was summarily dismissed.

At last, terms were arranged; the pawmines were to supply coolies, while the tsawbwa was to find carriage for forty mule-loads, and the 7th of April was appointed for the start. We were up with daylight, tents were speedily struck, and baggage packed for the march. The coolies soon assembled, and the area of our little camp was covered with wild-looking Kakhyens armed to the teeth with matchlocks, spears, and dahs, looking much more like a horde of banditti than peaceful porters. Their demeanour was in keeping with their appearance, and their dishonest purpose was evidenced by the bare-faced rivalry displayed by the different parties in seizing upon the packages which seemed most valuable, irrespective of size or weight. The precaution had been taken of telling off the escort into parties, with strict orders to prevent the exit of any baggage until all were in readiness for a start. The crisis was brought on by Sladen’s japanned tin cases. The youngest pawmine, who was first on the field, had appropriated them for his coolies, but when his brother, “Death’s Head,” appeared, very much excited, early as it was, with drink, he claimed them for his men. On his brother’s refusal to give them up, he lost all command over himself. After a violent outburst of passion, he made a dash at the gold sword which the king had presented to Sladen, and snatched it from the Burmese servant in charge. This attempt was frustrated by Williams, who with a vigorous wrench rescued the sword from “Death’s Head’s” grasp. Thus foiled, he attacked the Burmese clerk, who was taking down the names of the coolies, and threatened to cut him down. A general hubbub ensued, during which he rushed off to a camp fire, lit his slow-match, and advanced priming his matchlock, till he was close to Sladen, when he fired off his piece in the air. The consternation which ensued reached its climax when an assistant surveyor in a foolish panic fired his revolver. The Kakhyens showed that they had no relish for a fight, and, throwing down their loads, bolted in all directions. We of course remained quiet, while the tsawbwa showed more sense than could have been expected, calling upon the Kakhyens not to fly, and after a time order was restored. One of us followed “Death’s Head,” who had sat down at the end of the camp to reload his gun, and by a little persuasion got him to send his gun up to the village, and return to his duties. The loads were all arranged, and the escort had been so distributed that each set of coolies could be under surveillance, with a chain of communication between the van and rear-guard, while the coolies carrying the japanned tin cases were placed under the immediate supervision of armed followers, so that they could not “bolt” without creating an alarm. It was high noon before all was ready, and then the tsawbwa and pawmines, perhaps disgusted with these salutary precautions, announced that, as Manwyne could not be reached that day, our departure must be postponed till the morrow. This was pleasant after toiling six hours under a broiling sun, but we had nothing to oppose to native caprice save patience, strongly tempered with misgivings, which proved to be correct. The next morning no coolies appeared, and the pawmines came down to say that they could not fulfil their promise, as the tsawbwa had refused his co-operation. The chief himself soon afterwards arrived to lay the onus of the failure on the pawmines. A probable instigator of the whole scheme was the Nanlyaw tamone, who, after a long absence, suddenly presented himself in our camp, and whom Sladen, having had repeated proofs of his machinations, at once arrested as a spy; but at the urgent intercession of his friends, the pawmines, he was dismissed with a strong caution not to show himself again in our vicinity.

At this juncture, when all hope of extrication from our Ponsee prison seemed to have vanished, letters arrived from the governor of Momien, informing Sladen that he was about to take the field in person, with a strong force, to attack Li-sieh-tai, and drive him from his stronghold of Mawphoo. The letters further recommended us not to attempt to advance beyond Manwyne until advices should reach us of the defeat of the Chinese partisan. A second letter was a circular addressed to the Kakhyen chiefs, exhorting them to give all possible aid to the expedition. This at once gave a vantage ground, from which to deal with our highland friends, and it was improved by Sladen. Kakhyens, Burmese, and Shans had alike conceived extravagant ideas of the value of our baggage, and showed beyond doubt that the hope of getting possession of all, or a part of it, was a strong motive of their action or inaction. The leader therefore began to proclaim on all sides that though we had cheerfully endured privations and delays, in the hope of thoroughly conciliating the natives, they were not to imagine our patience to be inexhaustible. If we should be compelled to abandon all or any part of our baggage, it would be piled up and burned before our departure; thus they would lose their expected plunder, and incur the risk of future reprisals, or demands for compensation, and, above all, certainly alienate those who sought to be their friends. To this the chiefs replied in substance as follows: “Do not blame us for your misfortunes; we have been always in doubt how to act, on account of the many warnings we have received against aiding your progress. Now we know you. You have always been kind to us, and are a powerful people.”

Vexatious and harassing as had been our detention at Ponsee, it is certain that it would have been before this period quite impossible to proceed beyond Manwyne, and our residence among these semi-savage tribes served to convert their first suspicions into confidence, and to impress them with the value of our friendship. The uniform kindness with which all just services were requited, as contrasted with the treatment to which they had hitherto been subjected in their dealings with other races, especially with the Burmese, gradually worked its effect.

At this time letters were received through Burmese agency, from no less a person than Moung Shuay Yah, who since his treacherous desertion had never been heard of. Now all of a sudden his name was mentioned ad nauseam by the Burmese followers, and two Kakhyens arrived with letters purporting to have been written at some halting-place in the Shan country; but the bearers contradicted each other, and could not tell when, or from whom, they had received the letters. Next day, another letter was brought by one of the silver mining party, which, he said, Moung Shuay Yah had given him fourteen days before, but which he had forgotten to deliver. The fact was the interpreter had started for Momien, having heard of the change of our prospects, and our probable advance to that city. As it was needful, if possible, to save appearances, Moung Shuay Yah in his letter declared that he had been obliged to fly to save his life from the anger of Sala. Fortunately his place was by this time well supplied by Moung Mo, whom, it may be remembered, Sala had carried off with him, but who had returned and placed himself at Sladen’s disposal. He amply corroborated all that had been before told us of the efforts of the Bhamô people to obstruct our progress. Orders had been received from Mandalay, conveying the king’s displeasure at our detention at Ponsee, and authorising Sala to take us to Manwyne, but he had replied that after being induced by the Burmese of Bhamô to compromise himself with us, he would have nothing further to do with it.

It was supposed by our leader that the express object of stationing the armed miners at Ponsee was to deter the Kakhyens from helping us. Moung Mo, in addition, assured us that he had ascertained that Li-sieh-tai had sworn to oppose any attempt on our part to penetrate the Shan states, and he advised us on no account to proceed to Manwyne without an intimation from the Panthays that the road was open. An important circumstance occurred at this time in the arrival of messengers and a Chinese interpreter from Momien. They brought no letters, but were charged by the Tah-sa-kon[22] to make personal inquiries into the real objects of the mission and our circumstances at Ponsee. It transpired that letters from Bhamô had informed the governor that we represented a powerful nation in alliance with the Chinese, and foes to the Mahommedans all over the world, and that our real object was to destroy the Panthay dominion in Yunnan.

Sladen thoroughly dispelled these suspicions, and sent away the envoys completely satisfied as to the genuineness of our pacific intentions. The probabilities of an advance were, however, still remote and uncertain, and the wet season had fairly set in, marked by a constant succession of thunder and heavy rains. Dense masses of mist rolled up the valley like vast advancing curtains, shrouding the mountains in their gigantic folds, and producing an artificial twilight, and torrents of rain descended for three or four hours incessantly, soaking the tents; our waterproof blankets alone saving the inmates from complete saturation, but not from the utter discomfort of living in a puddle.

One storm deserves accurate description. Up to 4 P.M. of April 12th, the wind had been blowing in fitful cool gusts from the south-west, but at that hour there was a sudden lull; distant thunder was heard echoing among the mountains, and heavy black clouds came rolling up; a few drops of rain gave, as it were, the signal for a discharge of hailstones, or rather flakes of ice. The wind blew in violent gusts, and thunder rumbled over head, but the flashes of lightning were very faint. The hailstones were circular discs about the size of a shilling, flat on one side, and convex on the other. A white nucleus two-eighths of an inch in diameter, and in many cases with a prominent boss of clear ice on the convex side, formed the centre of a pellucid zone surrounded by an opaque one, in its turn encased in clear ice; the inner margin of this external zone was filled with a dark substance, resembling mud combined with delicate ice crystals; the whole disc strongly resembling a glass eye; when fractured, the nucleus separated itself as a small short column, flat at one end, and convex at the other.

During the storm, which lasted for twenty minutes, the aneroid rose from 26·62 to 26·65, and the attached thermometer registered 67°, the maximum heat during the day having been 84°.

It was evident that the season was closed for purposes of engineering survey and exploration, and this, combined with the reduced state of the exchequer, induced the leader of the expedition to address a circular to the members of the party, placing before them the facts, and suggesting that it would be for the interests of the public service that the numbers should be reduced in order to curtail the future expense of transport. It was necessary in fact to lighten the ship, and each was invited to consider how far he could assist in this needful work. Sladen had determined to remain, if necessary, for some months, until the opportunity should arrive to visit Momien, and at all hazards personally communicate with the Panthays; but he felt that he ought to place it in the power of the other members of the expedition to return, especially as the work which some of them had been despatched to effect could not be performed. This circular was sent round on the 17th, and the news of the fall of Mawphoo and the utter defeat of Li-sieh-tai reached us on the 18th of April, and was afterwards fully confirmed by despatches from the Tah-sa-kon, announcing his victory and writing to us to advance under the protection of all the chiefs en route. Our friends the tsawbwa and his pawmines, who had been day by day “making believe,” as children say, to discuss plans for procuring mules, were evidently much influenced by this; but they could not help showing their greed for rupees, and their continual demand was that three hundred should be paid before starting.

It was only later on that we learned that all these Kakhyens, especially Sala, had always been steady adherents of Li-sieh-tai, and that his utter defeat made them thoroughly anxious to conciliate the victorious Panthays.

The tsawbwa presented himself in a very penitent mood, and, confessing all his past misconduct, averred his determination to give up drink and debauchery and do his duty as a chief. Linking his fingers together with an expressive shake, he vowed leal service to his English friends, and then started off in company with his head pawmine on the road to Manwyne, where he expected to meet the Seray chief, and arrange means for our transport.

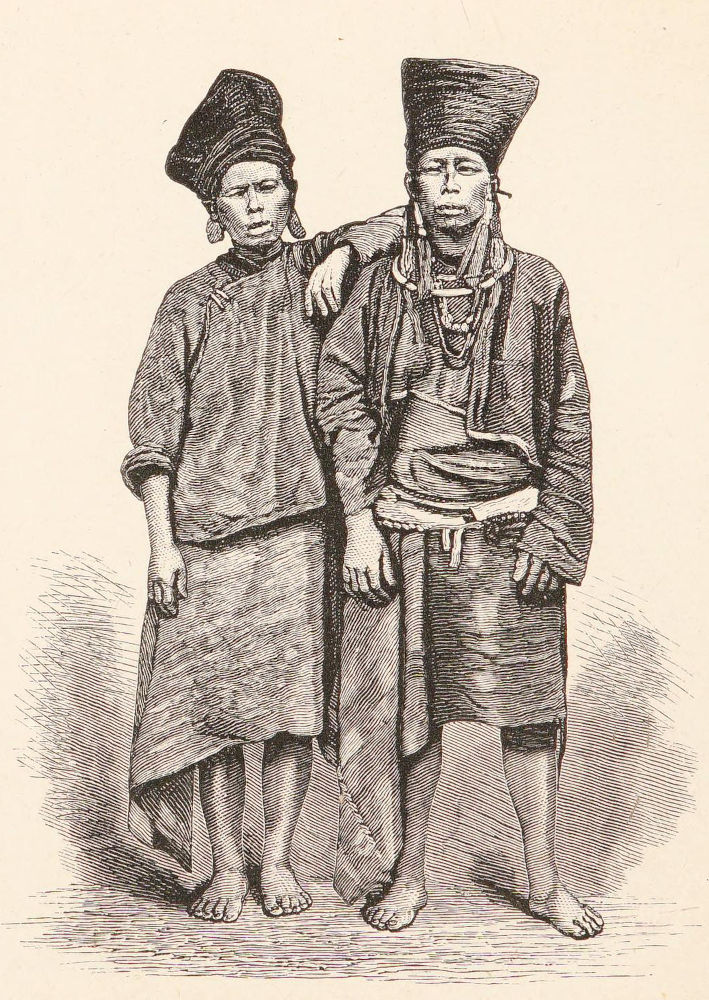

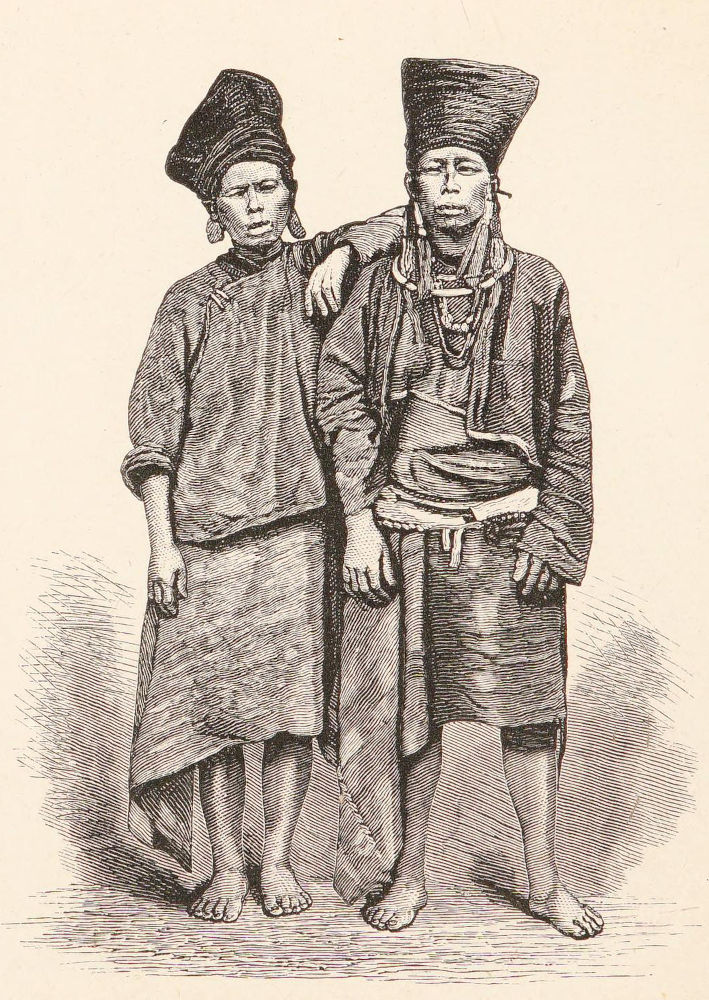

As if a new order of things had set in, our camp now was daily crowded by Kakhyens, all in the highest good humour. The women of the village came down en masse, bringing presents of fowls, eggs, sheroo, and rice, but the fair ones had an eye to business; beads, looking-glasses, bright new silver coins, and what they seemed most to prize, red cloth, were in great demand. A brisk trade was driven in the various ornaments, and they stripped off their bead necklaces and ratan girdles and leggings with great glee, and even a bell-girdle, the distinctive ornament of Kakhyen aristocracy, which hitherto even rupees had failed to secure, was now acquired in return for red cloth; indeed, it seemed quite possible to purchase a Kakhyen belle, ornaments, and all, for a few yards of the much prized material; and they returned home with great glee, shorn of their decorations, but rich in beads and cloth. Some came to solicit medical aid; cases of severe ulcerations, caused probably by their labour in the jungle, and aggravated by dirt, being common. The gratitude evinced for the relief given was touchingly shown by the presents, deposited with a fearful humility that showed the donor’s belief in the intimate connection between the doctor and the nats. Every day both chiefs and people from the more distant villages flocked in, and none came empty-handed. Gifts of rice, vegetables, tobacco, and sheroo, were brought not merely in the hope of return presents, but evidently as signs of amity. There could be no mistaking their feeling, that strangers who behaved with kindness and justice were welcome. These poor hill people had hardly ever known what it was to be treated with confidence; on either side, Burmese and Chinese had wronged and oppressed them. Monsig. Bigandet states that they had formerly been characterised by a genial kindliness and ready hospitality to strangers, but that the cruel treatment they experienced in Burmese towns, and the fraudulent evasion of payment for their services, had rendered them suspicious, greedy, and treacherous. It is not to be wondered at if the presence among them of strangers of an unknown race, escorted by an armed force, should at first have been regarded by them with fear and dislike, and it is with a modest pride that we recall the kindly confidence in the strangers which had sprung up towards the end of our long detention at Ponsee. The people from the distant villages continually asked, “Why did you not come our way? we should have then had some of the good things that you have brought for the Ponsee people.” The camp was perpetually full; the men, after curiously inspecting the many wonders that presented themselves, chatted and smoked with our followers; and the women, old and young, eagerly petitioned for small hand glasses, and black or green beads, the latter being most valued, and straightway converted their prizes into personal decorations. The young women formed in lines, each clasping her neighbour in a coquettish embrace, their shyness had vanished, they chatted and flirted freely, and did not even flinch from being photographed.

The friendly intercourse with these visitors gave us most welcome opportunities of inquiry into their customs, their national and social life. There was no backwardness in answering any questions, and the record of delays and difficulties may be well interrupted by a few pages devoted to these mountaineers. Those of whom we saw the most were all dwellers to the north of the Tapeng, but some of the visitors came from the southern hills, and the general characteristics distinguish both these and the clans visited by us on the return journey, who seem to be more civilised than their northern congeners. It is right here to acknowledge that the following account of this people has been rendered fuller and more accurate by the use of some notes furnished by Major Sladen from accounts given by natives, and by the use of a valuable memoir on the territories written by the learned and indefatigable missionary, Bishop Bigandet, whose warmest sympathies have been called out for these poor mountaineers, of whom he said, “It is of the utmost importance to know them, their character and habits, and to be prepared to secure their good will, whenever the thought of opening communications with Western China shall have been seriously entertained.”

KAKHYEN MEN.

KAKHYEN MATRONS.