CHAPTER V.

THE KAKHYENS.

The Kakhyens or Kakoos—The clans—Their chiefs—Mountain villages—Cultivation and crops—Personal appearance—Costume—Arms and implements—Female dress and ornaments—Women’s work—Sheroo—Morals—Marriage—Music—Births—Funerals—Religion—Language—Character—How to deal with them—Our party.

From the summit of the lofty hill, fully two thousand feet above our camp, called Shitee-doung, which it became possible to ascend during the latter part of our stay, an extensive view was obtained. From it to the north a sea of hills extended as far as the eye could reach; to the south stretched ranges of hills covered with forest, save where little clearings showed the presence of villages; to the north-east lofty parallel ranges closed in a narrow valley with a river winding down it. These hills are the country of the Kakhyens. These mountaineers belong to the widely spread race that under the name of Singphos, Kakoos, &c. occupy the hills defining the Irawady basin, up to the wall of the Khamti plain, and are probably cognate with the hill tribes of the Mishmees and Nagas. The name Kakhyen is a Burmese appellation; they invariably designating themselves as Chingpaw, or “men.”[23] By their own account the hills to the north of the Tapeng, for a month’s journey, are occupied by kindred tribes. South of the Tapeng, they occupy the hills as far as the latitude of Tagoung, and, as mentioned, were met with on our voyage near the second defile. To the east, they are found occupying the hills, and, intermixed with the Shans and Chinese, almost to Momien. Here they, as it were, run into the Leesaws, who may be a cognate, but are not an identical, race. The two chief tribes in the hills of the Tapeng valley are the Lakone and Kowrie or Kowlie, but numerous subdivisions of clans occur. All are said to have originally come from the Kakoos’ country, north-east of Mogoung; and Shans informed us that two hundred years ago Kakhyens were unknown in Sanda and Hotha valleys. To give one instance of their migrations. The Lakone tribe have at a very recent period driven the Kowlies from the northern to the southern banks of the Tapeng. A Lakone chief, having married the daughter of a Kowlie, asked permission to cultivate land belonging to his father-in-law; receiving a refusal, he took forcible possession, and drove the Kowlies across the river to the hills where they now dwell.

Among these hill tribes the patriarchal system of government has hitherto universally prevailed, although a certain, or rather uncertain, obedience is nominally due to Burmese or Chinese authorities. Thus the Ponsee and Ponline chiefs had each received a gold umbrella and the title of papada raza from the king of Burma. Each clan is ruled by an hereditary chief or tsawbwa, assisted by lieutenants or pawmines, who adjudicate all disputes among the villagers. Their office is also hereditary, and properly limited to the eldest son, whereas the chieftainship descends to the youngest son, or, failing sons, to the youngest surviving brother. The land also follows this law of inheritance, the younger sons in all cases inheriting, while the elder go forth and clear wild land for themselves. Between Tsitkaw and Manwyne seven clans under separate chiefs are met with, each chief considering himself entitled to exact a toll of four annas per mule-load from travellers through his district. The chieftain’s goodwill being secured by payment of his toll or blackmail, that of the people follows as a matter of course. When the traveller quits the lands of one chief, he is handed over by his guide to the next headman, and is as safe with him as with the former. The tsawbwa is the nominal owner of the land, but a suggestion to a villager that the chief might evict him from his holding was replied to by a significant sawing motion of the hand across the throat. As a general rule, the chief owns the slaves found everywhere among these people. Most have been stolen as children, but adults are also kidnapped. The women become concubines, the men are well treated if industrious and willing. The children of slaves belong to the owner, but really are as well treated as the members of his family. When a tsawbwa marries, he is expected to present a slave to his father-in-law, among the other gifts. The market value of a boy or girl is about forty rupees, but that of a man not more than twenty to thirty rupees, or a buffalo.

Every house pays the chief an annual tribute of a basket of rice. Whenever a buffalo is killed, a quarter is presented to him. He is usually a trader, and, besides the receipt of tolls, derives a profit from the hire of mules or coolies for transport. Save in this respect, it was impossible to help being reminded of Scottish highland clans of the olden time, so many were the points of resemblance that occurred in the customs and indeed character of these mountaineers, though, to avert all possible indignation, I hasten to add that no parallel is intended to be drawn, especially as regards their morals or social life.

The Kakhyen villages are always situated near a perennial mountain stream, generally in a sheltered glen, or straggling with their enclosures up a gentle slope, covering a mile of ground. The houses, which usually face eastwards, are all built on the same plan as that tenanted by us at Ponline. The most usual dimensions are about one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet in length, and forty to fifty feet in breadth. These large bamboo structures are veritable barracks. The first room is hospitably reserved for strangers; the others form the apartments of several families, connected by blood or marriage, which compose the household community. The back entrance is reserved for the use of the members of these families. A serious demand for compensation arose out of the inadvertence of one of our servants who entered by the family door, and thus provoked the domestic nat. The projecting eaves, supported by posts which are adorned with the skulls of buffaloes and pigs, form a portico, where men and women lounge or work by day, and at night the live stock—buffaloes, mules, ponies, pigs, and poultry—are housed, while a bamboo fence guards them from possible thief or leopard.

Near the houses are small enclosures, where white-flowered poppies, plantains, and indigo are cultivated; paddy and maize are grown together on the adjacent slopes and knolls, which are carefully scarped in terraces, presenting often the appearance of an amphitheatre. The stream is dammed near the highest point, and directed so as to overflow the terraces and rejoin the channel at the base. Bamboo conduits are sometimes used to convey the water to paddy fields or distant houses. Fresh clearings are also made every year by felling and burning the forest on the hillsides. Near every village disused paths may be seen, which have been cut to former clearings, and along which a little canal has been carried. The cleared ground is broken up with a rude hoe, but in the cultivated terraces wooden ploughs are used. Excessive rain, which makes the paddy weak and the yield scanty, is most dreaded. Generally, the natural fertility of the soil more than repays the rude husbandry with beautiful crops of rice, maize, cotton, and tobacco, of excellent quality. Near the villages, peaches, pomegranates, and guavas are grown; and the forests abound with chestnuts, plums, cherries, and various wild brambleberries. On the higher slopes, oaks and birches grow in abundance, and large areas are covered with Cinnamomum caudatum and C. cassia, the oil of which is commonly sold as oil of cinnamon. Thousands of these trees are annually felled to clear new ground for cultivation and burned where they lie. Another natural production is the tea plant (Camellia thea), which grows freely on the eastern side of the hills, and suggested dreams of future tea plantations, cultivated by improved Kakhyens or imported Shans and Paloungs.

Among the inhabitants of the villages, both those who visited our camp and the southern hillmen seen on the homeward route, the variety of faces is striking. This may be probably owing to admixture of Shan and Burmese blood, but two types may be said to predominate; the one with a fine outline of features, which recalled the womanly faces of the Cacharies and Lepchas of Sikkim. In it the oblique eye is very strongly marked, and the face is a longish, rather compressed oval, with pointed chin, aquiline nose, and prominent malars. One Kakhyen belle met with at Bhamô, with large lustrous eyes and fair skin, might almost have passed for a European. The other and by far the most prevalent type is probably the true Chingpaw, presenting a short, round face, with low forehead and very prominent malars. The ugliness of the slightly oblique eyes, separated by a wide space, the broad nose, thick protruding lips, and broad square chin, is only redeemed by the good-humoured expression. The hair and eyes are usually a dark shade of brown, and the complexion is a dirty buff. The average height for men is from five feet to five feet six inches, and four feet six inches to five feet for women. The limbs are slight, though well formed, one peculiarity being the disproportionate shortness of the legs. This is also observable among the Karens, to whom the Kakhyens bear a general resemblance, suggesting a common origin, which is further indicated by their language. Though not muscular, they are very agile, and the young girls bound like deer along the hill-paths, their loose dark locks streaming behind them. They bring down from the hills loads of firewood and deal planks which we found as much as we could lift. However interesting and picturesque their appearance may be, closer inspection dissolves the enchantment lent by distance. Both persons and clothes appear never to have been washed, and the dress, once put on, is never changed till it is worn to pieces. Neither men nor women use combs, and the state of the thick matted felt of hair can better be imagined than described. Although they never seemed to wash except faces, hands, and feet, some of the men were good swimmers and divers, and proudly exhibited their skill, disclosing thereby the fact that their bodies were tattooed with blue dots, chiefly on the chest and back. The dress of the men usually consists of a Shan jacket and short breeches of blue cotton cloth, supported by a cotton girdle. The hair is coiled in a blue or sometimes a red turban; the moustache and beard are very scanty, but their custom of eradicating the natural growth renders it hard to judge. They insert in the lobe of the ear a piece of bamboo, or a lappet of embroidered red cloth, a leaf or flower, or a piece of paper, our old newspapers being in great request; and a number of fine ratan rings encircle the leg below the knee. It seemed to us that the Kakhyen men were ready to adopt any dress; some even wore their hair in the Chinese pigtail. The “Red Pawmine,” on grand occasions, turned out in a bright red turban, rose-checked breeches, and a red blanket over his shoulders. The chiefs usually wear Chinese padded jackets, leggings made of rolls of blue cloth, and Shan shoes. They are distinguished, especially in the case of those who rigidly adhere to the ancient Kakhyen costume, by neck-hoops of silver, resembling Celtic torques, and the necklace of beads or cylinders of an ochreous earth. These are found in the Mogoung district, and are highly valued, being reputed to be the authentic handiwork of the earth nats. Some Kakoos met with at Sanda wore a broad piece of blue cotton cloth, with a red embroidered border of woollen stuff, like a kilt, reaching to the knee. This seems to be the true Kakhyen dress; and they also wore their hair uncovered, and cut straight across the forehead, like the Kakhyen maidens. No hillman is ever seen without his dah, or knife; it is half sheathed in wood, and suspended to a ratan hoop covered with embroidered cloth and adorned by a leopard’s tooth. This is slung over the right shoulder, so as to bring the hilt in front ready to the grasp of the right hand. Two sorts of dahs are in use: one the long sword, such as the Thibetans use, two feet and a half in length, with a long cylindrical wooden hilt, bound with cord and finished with a red tassel. The other is shorter and broader, widening from the hilt to the truncated tip. This knife the Burmese call “the Kakhyen’s chief”; it is wielded with great dexterity either to cut down trees or men, or to execute the fine lineal tracery with which their bamboo opium pipes and fan cases are decorated. It is appealed to in every argument, and drawn on visible foes and invisible nats with equal readiness. On one occasion we espied a woman on the hillside writhing on the ground in evident pain. A passing villager came to her assistance, and at once out flashed his dah, with which he executed several cuts in the air over the prostrate woman. This was to drive away the nat who had taken possession; he then threw earth over her head, and ran off to the village to procure help to carry her home. During the latter part of our stay, one of the police escort, during a chaffing argument with a Kakhyen visitor, was without warning felled by a blow of the dah. The savage decamped to the jungle, leaving the sepoy bleeding from a gash on his head, and another on the arm, with which he had warded off the blow and so saved his skull from being split. These dahs are made by the Shans of the Hotha valley, who are the itinerant smiths of the country. Other arms are a long matchlock, and a cross-bow, with arrows poisoned with the juice of an aconitum. They are much used in hunting; the flesh round the wound being cut out, the rest of the animal is eaten without danger. An invariable article of equipment is an embroidered bag worn over the right shoulder, containing pipe, tobacco, lime and betel box, money, and a bamboo flask of sheroo. A most ingenious apparatus supplies a light for the constant pipe. It resembles a child’s popgun, and consists of a small cylinder four inches long, open at one end, into which is very tightly fitted a piston, with a cup-shaped cavity at the lower end. In it, a small pellet of tinder is placed, the piston is driven down smartly, and as quickly withdrawn, when the tinder is found to be ignited.

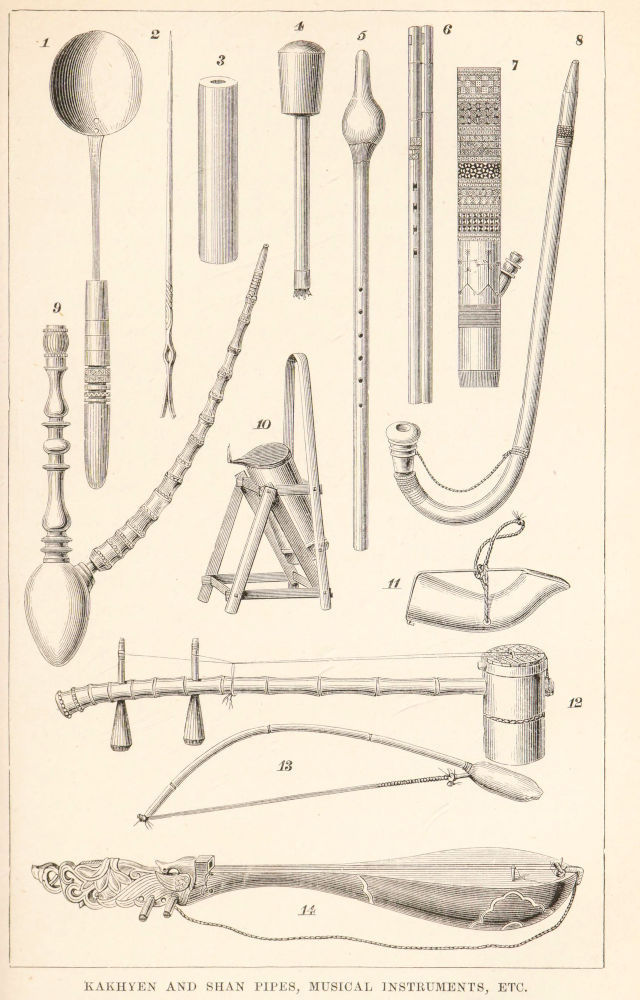

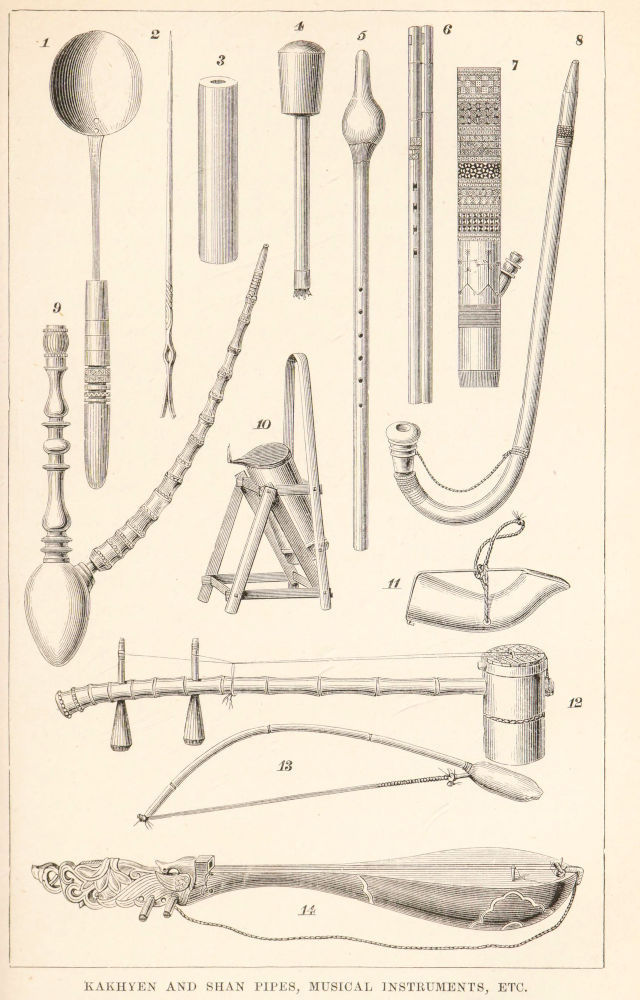

KAKHYEN AND SHAN PIPES, MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS, ETC.

Fig. 1. Kakhyen ladle for preparing opium.

2. Kakhyen opium forceps.

3. 4. Kakhyen cylinder and piston for striking fire.

5. Shan flute with gourd mouthpiece.

6. Kakhyen double flute.

7. Kakhyen opium hookah (bamboo).

8. Kakhyen opium pipe.

9. Kakhyen opium hookah, the mouthpiece made of the underground stem and the water receptacle of the segment of a remarkable bamboo with swollen internodes.

10. Chinese bamboo lamp.

11. Shan powder flask.

12. Shan violin.

13. Bow for ditto.

14. Shan guitar.

It is worth recording that the men invariably smoke opium, but not to excess; rarely, if ever, did we see them use tobacco for smoking, though they were addicted to chewing it. The juice of the poppy, exuding from incisions made in the green capsules, is collected on plantain leaves, which are dried, and in this form the opium is smoked either in hookahs made of the segment of a peculiarly shaped bamboo or in brass pipes of Chinese manufacture. Whether the cultivation and use of opium have spread from Assam or from Yunnan is uncertain, but we found it universal from the Burmese plain to Momien, although the method of smoking it among the Kakhyens differs altogether from that of the Chinese. Dr. Bayfield, in 1837, observed of the Singphos, on the western side of the Irawady valley, that, “from whatever source derived, the cultivation of the poppy is now universal;” and he describes the methods of collection and use as the same, save that coarse cloth was used instead of leaves.

The men rarely employ themselves in manual labour; a few of the more industrious assist the women to fell the jungle and set it on fire, but most of this labour is left to the women. In general, the men till the land; but between the seasons, they wander from house to house, and village to village, gossiping, drinking, or smoking. Journeys to dispose of produce, or carry goods, hunting excursions, and occasional fights or forays, are not reckoned labour. They do not work in metals, but are very skilful in adorning bamboos or wooden implements with carving. The designs of their tracery are the simplest combinations of straight lines, and rude figures of birds and animals, characteristic of the most primitive art.

The Kakhyen women have adopted the short loose Shan jacket of blue cotton, slashed with red cloth, variously ornamented, according to the means of the wearer, with cowries and silver. This covers the arms and breast, but leaves the waist exposed, save for a profusion of ratan girdles, adorned with lines of white seeds. These also support the kirtle or kilt, which reaches from the hips to the knee, the border of the skirt being chequered in red, blue, and yellow. Cowries form a favourite ornamentation of every part of the dress, and the daughters of chiefs wear broad belts of these shells. Besides the distinctive bell-girdle, fine ratan rings encircle the leg below the knee, but no shoes are worn. Most of the matrons coil their hair in the folds of the Shan turban, but the original Chingpaw head-dress is a puggery of embroidered cloth, twisted round the head, while the end, fringed with beads, falls gracefully on the shoulder. Unmarried women wear no head-dress, and cut their hair square across the forehead in a fashion not unknown in England, while their back hair, unrestrained by any fastening, streams down behind. The ears are pierced both through the lobes and upper cartilage. In the latter orifice is inserted a lappet of embroidered cloth tasselled with small green and black beads; silver tubes, reaching to the shoulder, are also worn by the wealthier belles, while the poorer display fresh flowers or leaves. Anything seems convertible into an ear-ring: thus a cheroot, or, as seen by us, a freshly plucked leek, is stuck into the ear. All who can, wear necklaces of beads, but silver hoops called gerees, and the komoung of red ochreous beads, are peculiar to the necks of high-born damsels.

It has been remarked that the men are averse to labour, but the lot of all women irrespective of rank is one of drudgery. They are not allowed to eat with the men, and are looked on as mere beasts of burden, valued only for their usefulness; but they seem contented with their lot, and are always cheerful and light-hearted. Their brisk activity forms a pleasing contrast to the lounging idleness of their lords. Much, if not most, of the field-work falls to their share, and their daily routine is one of incessant and hard labour. Their first duty in the morning is to clean and crush the rice for the daily consumption, and late at night the dull thud of the heavy pestle, with the accompaniments of their regular wild cry and the jingling of the bell-girdles, was to be heard. They fetch water from the stream, and firewood from the jungle. This latter is a most laborious task, as the girls have to search for dry wood, cut it into faggots, and bring it home on their backs. Their bare legs are often lacerated in the jungle, and the wounds, aggravated by dirt and neglect, form intractable ulcers. Many such cases were brought to our camp for treatment. Another effect of the hard work and exposure is to be observed in the frequency of grey hair among the young women, the matted locks of even girls of ten and twelve years being abundantly silvered as if by premature old age.

Their ordinary house labours include the preparation of sheroo, or Kakhyen beer, a beverage always in demand. This is regarded as a serious, almost sacred task, the women, while engaged in it, having to live in almost vestal seclusion. Certain herbs and roots dried in the sun are mixed with chillies and ginger, to avert the interference of malignant nats; the mixture is pulverised with some rice in a mortar, and reduced to a paste which is carefully preserved in the form of cakes, wrapped in mats. Crushed rice mixed with fresh plantains is steeped for half a day, and allowed to dry. It is next boiled, or “mashed,” with a due proportion of the “medicine” or powdered cake in a paungyaung, or wooden tub, placed within a copper caldron, from which it is, after cooling and fermenting for a week in a leaf-covered basket, transferred to a closely covered earthen jar. After twenty days the sheroo is fit to drink, but is better if left for six months. This forms the stock, to which water is added, and the beverage is offered in a bamboo, closed with a fresh plantain leaf. This liquor resembles very small beer, but is pleasant and refreshing. A similar beverage is found among the Lepchas of Darjeeling, who imbibe it through a reed, the Looshais and Nagas. The Khyens and Karens also prepare a rice-beer like the congee of the Burmese; the Nagas also prepare “moad” from rice, and the Khamtis and Singphos of the Hoo-kong valley distil a spirit which the latter call sahoo; but the Kakhyens procure all their supplies of samshu, or rice-spirit, from the Shan-Chinese.

It is naturally the business of the women to spin, dye, and weave the home-grown cotton. Their loom is of a primitive form, the same as that used among the Khyens, the Munipoories, and other tribes on the north-east of Assam. One end of the warp is held in position by pegs driven into the ground, and the other is kept on the stretch by a broad leather strap fastened round the back of the woman as she sits on the ground with her legs straight before her. A long piece of wood keeps the threads of the warp open, so that the shuttle, which is thirty inches long, and worked by both hands, can pass easily. With this they produce a strong thick cloth, and weave fanciful patterns of red, green, and yellow. They are also adepts at embroidery in silk and cotton, which is only applied to the decoration of the bags or havresacks worn by the men.

The code of morality of the Kakhyens has been variously represented. Unchastity before marriage is certainly not regarded as a disgrace. If possible, the parents of the girl endeavour to get the lovers married, but it is not an imperative duty. Should, however, an unmarried girl die enceinte, the father of the child is bound to compensate her parents by the present of a slave, a buffalo, a dah, and other articles, and to give a feast to the inmates of the house. Failing this, he is liable to be sold as a slave. This arises from the value set upon a marriageable daughter, both as regards her present working power and her future price as a wife, which is not lessened by an indiscretion.

Infidelity after marriage is a crime which the husband may punish on the spot by the death of both the offenders. In case of elopement of a wife, the husband is entitled to recover damages, fixed at double the amount expended by him at his marriage. For this the relatives and clansmen of the lover are held liable on pain of a feud.

The ceremony of marriage, besides the religious rites, combines the idea of purchase from the parents with that of abduction, so frequently found to underlie the nuptial rites of widely separated races. An essential preliminary is to get the diviner to predict the general fortune of the intended bride. Some article of her dress or ornaments is procured, and handed to the seer, who, we may suppose, being thereby brought en rapport with her, proceeds to consult omens and predict her bedeen or destiny. If auspicious, messengers bearing presents are sent to make proposals to the girl’s parents, who specify the dowry required and agreed to by the envoys. All being adjusted, two messengers are sent from the bridegroom to inform the bride’s friends that such a day is appointed for the marriage. They are liberally feasted, and escorted home by two of her relatives, who promise to be duly prepared. When the day comes, five young men and girls set out from the bridegroom’s village to that of the bride, where they wait till nightfall in a neighbouring house. At dusk the bride is brought thither by one of the stranger girls, as it were, without the knowledge of her parents, and told that these men have come to claim her. They all set out at once for the bridegroom’s village. In the morning the bride is placed under a closed canopy, outside the bridegroom’s house. Presently there arrives a party of young men from her village, to search, as they say, for one of their girls who has been stolen. They are invited to look under the canopy, and bidden, if they will, to take the girl away; but they reply, “It is well; let her remain where she is.”

While a buffalo, &c. are being killed as a sacrifice, the bridegroom hands over the dowry, and exhibits the trousseau provided for his bride. A wealthy Kakhyen pays for his wife a female slave, ten buffaloes, ten spears, ten dahs, ten pieces of silver, a gong, two suits of clothes, a matchlock, and an iron cooking pot. He also presents clothes and silver to the bridesmaids, and defrays the expense of the feast. Meanwhile the toomsa, or officiating priest, has arranged bunches of fresh grass, pressed down with bamboos at regular intervals, so as to form a carpet between the canopy and the bridegroom’s house. The household nats are then invoked, and a libation of sheroo and water poured out. Fowls, &c. are then killed, and their blood is sprinkled on the grass path, over which the bride and her attendants pass to the house, and offer boiled eggs, ginger, and dried fish to the household deities. This concludes the ceremony, in which the bridegroom takes no part. A grand feast follows. Besides the ordinary fare of rice, plantains, and dried fish and pork, the beef of the sacrificed buffalo and the venison of the barking deer, all cooked in large iron pots, imported from Yunnan, are the viands. Abundant supplies of sheroo and Chinese samshu prepare the guests for the dance.

The orchestra consists of a drum formed of a hollowed tree stem, covered at both ends with the skin of the barking deer, a sort of jews-harp of bamboo, which gives a very clear, almost metallic, tone, and a single or double flute, with a piece of metal inside a long slit, which the performer covers with his mouth. He also accompanies the strain with a peculiar whirring noise, produced in his throat. The marriage feast ends, like all their festivities, in great drunkenness, disorder, and often in a fight.

Breach of promise is made a cause of feud, the friends of the aggrieved fair one making it a point of honour to attack the village of the offender. The curious custom obtains that a widow becomes the wife of the senior brother-in-law, even though he be already married. The day after the birth of a child, the household’s nats are propitiated by offerings of sheroo and the sacrifice of a hog. The flesh is divided into three portions, one for the toomsa, another for the slayer and cook, and the third for the head of the household. The entrails, with eggs, fish, and ginger, are placed on the altars, all the villagers are bidden to a feast, and sheroo is handed round in order of seniority. After all have drunk, the oldest man rises and, pointing to the infant, says, “That boy, or girl, is named so and so.” When a Kakhyen dies, the news is announced by the discharge of matchlocks. This is a signal for all to repair to the house of death. Some cut bamboos and timber for the coffin, others prepare for the funeral rites. A circle of bamboos is driven into the ground, slanting outwards, so that the upper circle is much wider than the base. To each a small flag is fastened, grass is placed between this circle and the house, and the toomsa scatters grass over the bamboos, and pours a libation of sheroo. A hog is then slaughtered, and the flesh cooked and distributed, the skull being fixed on one of the bamboos. The coffin is made of the hollowed trunk of a large tree, which the men fell with their dahs. Just before it falls, a fowl is killed by being dashed against the tottering stem. The place where the head is to rest is blackened with charcoal, and a lid constructed. The body is washed by men or matrons, according to sex, and dressed in new clothes. Some of the pork, boiled rice, and sheroo, are placed before it, and a piece of silver is inserted in the mouth to pay ferry dues over the streams the spirit may have to cross. It is then coffined and borne to the grave amidst the discharge of fire-arms. The grave is about three feet deep, and three pieces of wood are laid to support the coffin, which is covered with branches of trees before the earth is filled in. The old clothes of the deceased are laid on the mound, and sheroo is poured on it, the rest being drunk by the friends around it. In returning, the mourners strew ground rice along the path, and when near the village, they cleanse their legs and arms with fresh leaves. Before re-entering the house, all are lustrated with water by the toomsa with an asperge of grass, and pass over a bundle of grass sprinkled with the blood of a fowl sacrificed during their absence to the spirit of the dead. Eating and drinking wind up the day. Next morning an offering of a hog and sheroo is made to the spirit of the dead man, and a feast and dance are held till late at night, and resumed in the morning. A final sacrifice of a buffalo in honour of the household nats then takes place, and the toomsa breaks down the bamboo fence, after which the final death dance[24] successfully drives forth the spirit, which is believed to have been still lingering round its former dwelling. In the afternoon a trench is dug round the grave, and the conical cover already described is erected, the skulls of the hog and buffalo being affixed to the posts.

The bodies of those who have been killed by shot or steel are wrapped in a mat and buried in the jungle without any rites. A small open hut is erected over the spot for the use of the spirits, for whom also a dah, bag, and basket are placed. These spirits are believed to haunt the forests as munla, like the Burman tuhsais, or ghosts, and to have the power of entering into men and imparting a second sight of deeds of violence. Funeral rites are also denied to those who die of small-pox and to women dying in child-birth. In the latter case, the mother and her unborn child are believed to become a fearful compound vampyre. All the young people fly in terror from the house, and divination is resorted to, to discover what animal the evil spirit will devour, and another with which it will transmigrate. The first is sacrificed, and some of the flesh placed before the corpse; the second is hanged, and a grave dug in the direction to which the animal’s head pointed when dead. Here the corpse is buried with all the clothes and ornaments worn in life, and a wisp of straw is burned on its face, before the leaves and earth are filled in. All property of the deceased is burned on the grave, and a hut erected over it. The death dance takes place, to drive the spirit from the house, in all cases. The former custom appears to have been to burn the body itself, with the house and all the clothes and ornaments used by the deceased. This also took place if the mother died during the month succeeding child-birth, and, according to one native statement, the infant also was thrown into the fire, with the address, “Take away your child;” but if previously any one claimed the child, saying, “Give me your child,” it was spared, and belonged to the adopting parent, the real father being unable at any time to reclaim it.

These ceremonies show the character of the religion of the people. Hemmed in as they are by Buddhist populations, they adhere to the ancient form of worship of good and evil spirits. The French missionaries have been unable to produce any effect upon them. A vague idea of a Supreme Being exists among them, as they speak of a nat in the form of a man named Shingrawah, who created everything. They do not worship, but reverence him, “because he is very big.” As their funeral rites show, they believe in a future existence. Tsojah is the abode of good men; and those who die violent deaths, and bad characters generally, go to Marai. To questions as to the place and conditions of these, an intelligent Kakhyen answered, “How can I tell? no one knows anything.”

The objects of worship are the nats benign or malignant; the first such as Sinlah, the sky spirit, who gives rain and good crops; Chan and Shitah, who cause the sun and moon to rise. These they worship, “because their fathers did so, and told their children that they were good.” Cringwan is the beneficent patron of agriculture, but the malignant nats must be bribed not to ruin the crops. When the ground is cleared for sowing, Masoo is appeased with pork and fowls, buried at the foot of the village altars; when the paddy is eared, buffaloes and pigs are sacrificed to Cajat. A man about to travel is placed under the care of Muron, the toomsa, after due sacrifices, requesting him to “tell the other nats not to harm that man.”

Neglect of Mowlain will result in the want of compraw, or silver, the great object of a Kakhyen’s desire, and if hunters forbear offerings to Chitong, some one will be killed by stag or tiger. Chitong and Muron are two of ten brothers, who have an especial interest in Kakhyen affairs, and another named Phee is the guardian of the night. Every hill, forest, and stream, has its own nat of greater or less power; every accident or illness is the work of some malignant or vindictive one of “these viewless ministers.” To discover who may be the particular nat, or how he is to be appeased, is the business of the toomsa. He prescribes and assists in all sacrifices, and calls the nats to receive their share, which with economical piety generally consists of the offal. The extraordinary method of consulting the will of the nats by a possessed medium has been already described. The meetway is distinct from a toomsa, or regular priest, but there is no sacerdotal caste, the succession being kept up by a natural selection and apprenticeship. The village toomsa practises augury from fowl bones, omens, and the fracture of burned nul grass, besides holding communication with the spirit world. Besides the occasional sacrifices, at seed-time a solemn sacrifice is offered to Ngka, the earth spirit. In this the whole community participates, and the next four days are observed as a strict sabbath, no work or journey being undertaken.

At harvest-time Sharoowa and his wife are worshipped in a similar manner by the chief and villagers. All animals sacrificed must be males, but a woman’s dress and ornaments are offered to the female nat. The namsyang, or tutelary nats of the village, are also husband and wife; he ruling the western and she the eastern portion; they are venerated twice a year with other nats by the tsawbwa. All the people repair to the head village, and the chief offers buffaloes, &c., and a grand feast is held. The skulls of the animals offered and eaten are affixed to the tsawbwa’s house, where they remain as memorials of his piety and hospitality.

These recurring seasons of seed-time in May and June and harvest-time in December seemed to us to be the only divisions of time known to these mountaineers, but they were said to have a succession of months.[25]

The language of the Kakhyens is monosyllabic, and is spoken in an ascending tone, every sentence ending in a long-drawn “ee,” in a higher key, thus—“Chingpaw poong-doon tan-key-ing eee?” “Do the Kakhyens dance?” Monsig. Bigandet says: “It is the same as used by all the Singpho tribes, and bears a great resemblance to that of the Abors and Mishmees, and other tribes of the south-western spurs of the Himalayas. The pronunciation is soft and easy, and the construction of sentences simple and direct as in English. It is totally different from the Burmese, and belongs to a completely different group.” We found very few that could speak Burmese, except the Ponline and other chiefs bordering the plain; but almost all the chiefs both north and south of the Tapeng, and many of their clansmen, could speak Chinese, and a few, such as the chiefs of Mattin, Seray, &c., could write Chinese; but the Kakhyens possess no written characters of their own.

As warriors the Kakhyens cannot be ranked high. Quarrelsome and revengeful as they are, prone to exact atonement for a wrong or feud to the last, their attacks are always made stealthily, and generally at night—they may be said to crouch and spring like the tiger. As hunters, so far as we could learn, they are not very daring, but our opportunities of observation were limited, and the hills about Ponsee did not seem to contain much animal life. Their chief quarry is the barking deer, but leopards and porcupines are said to be sometimes found, and wild elephants were reported as occasional visitors. The fierce and pugnacious bamboo rat is esteemed a dainty and valuable prize. The young lads set ingenious traps for jungle fowl and pheasants. A miniature fence of the stems of tall jungle grass is constructed down the hillside for two hundred feet, through which little runs are opened. At each a pliable bamboo is firmly fixed at one end, while the other is lightly fastened to the ground. A noose fixed to this end snares the birds, which are hoisted in the air like moles in the familiar trap. We also observed boys liming small birds in an ingenious manner, with a bird-lime obtained from the root of some plant. This was smeared on the prongs of a wooden trident fixed in a bamboo handle, which was hidden in the jungle bordering a path. On a cord across the trident, a number of ants were so fixed that they could move their wings; the constant flutter allured the birds to perch on the trident and be caught. The small boys were stimulated in the pursuit of “small deer” and all sorts of birds by the rewards given for any specimens. The collection and preservation of all manner of living things was a constant source of wonder to the Kakhyens, as well as of gain. Even the young tsawbwa caught the infection, and, moved either by greed or gratitude for medical help, brought in a young example of a red-faced monkey, closely allied to Macacus tibetanus (Milne-Edwards).

It will be evident that they are a perfectly wild race of mountaineers, supplying themselves with most of the necessaries of life by rude cultivation. They are altogether dependent on their neighbours for salt and dried fish; and as their own scanty crops furnish little superfluity, their great object is to obtain compraw, wherewith to purchase what they need. They rear no animals but pigs; and the buffaloes they own have been stolen from the plains. This habit of “cattle-lifting” causes them to be regarded as natural outlaws by the Burmese; hence the constant state of hostility and reprisals on both sides. Since the time of our visit the mountaineers have been better treated at Bhamô, and a zayat has been erected for their use outside the stockade, besides one built for them near the British Residency; but no Kakhyen can enter or leave the town without a pass, for which he has to pay toll, this licence-duty being farmed by residents in Bhamô. It must be owned that, whether their character has been deteriorated by knavish injustice on the part of Chinese traders, or high-handed extortion and wrong on the part of Burmese, they are at the present time lazy, thievish, and untrustworthy. Their savage curiosity leads them to pry into every package entrusted to them. During the return journey all the collecting-boxes were opened, and every specimen unrolled and examined, with what results of utter confusion may be imagined. They consider themselves entitled to levy blackmail on all passing through their districts, and each petty chief tries to represent himself as an independent tsawbwa, with a full control of the portion of route near his village.

As any mission or trade-convoy must, however, pass through their hills, and strong and impartial justice should characterise all our relations with them, it will not be thought presumption to suggest what appears to be the best and fairest method of dealing with them. It is thoroughly well established that the Kakhyens themselves possess no mules, or at least so few as to be insufficient for the carriage of any large amount of baggage or goods. When the chiefs have been employed to procure mules, they hire them from the Shans, acting thus as middle-men, and in our case making an exorbitant profit. Their incurable habits of pilfering and meddling curiosity render them unfit to be employed as porters. All beasts of burden, and coolies, if required, should be procured either in Burma or by direct agents, hiring them in the Shan districts subject to China; in the latter case no payments in advance should be made. The chiefs of the Kakhyens occupying the portion of the route lying within the Burmese frontier line should be summoned to Bhamô by the Burmese authorities at the instance of the British Resident, and, a proper sum, in recognition of their territorial dues, being fixed, should be informed that this will be paid at the Residency on the safe passage through their territory being accomplished and certified. A similar course can be pursued by communication with the Chinese authorities with regard to those who live within the Chinese frontier. The duties to be performed by the chiefs should be limited to guaranteeing an undisturbed passage, and providing such accommodation or supplies as may be required. With regard to provision for an open trade route, a fair tariff should be fixed upon: this has been done by the Chinese, and could be accomplished by the Burmese also. The mountain chiefs may then be required to keep the roads open and in repair, and to suppress any attempt at brigandage, on pain of being fined, and otherwise punished. It must be remarked, however, with all deference to the political branch of our service, that one cannot help thinking that it will be needful in all cases that our Residents should not issue independent summonses and orders to the hill chiefs. The ill-feeling of the Burmese has not unnaturally been excited by British officers dealing, independently of the Woon, with the chiefs, nominally at least, subordinate to him as the officer of the king of Burma. It is surely incumbent on the British Resident in the town of an independent foreign power to co-operate with and recognise the local authorities, and cultivate an entente cordiale with them. If this policy be systematically observed, the Burmese will be most fairly and properly held responsible for the conduct of the chiefs whom they claim to be dependent on their authority, and who have accepted titles and insignia from the king of Burma. It may seem fanciful to suggest ways and means of removing the difficulties of the route for a future trade; but the passage of a mission, or of future explorers of the interesting country beyond the Kakhyen hills, will be only thus made possible. The arrangements must be made with the Burmese and the Chinese; the Kakhyens, being only regarded as outlying people, paid their dues, not from fear, but from generous justice; while they are sternly repressed, and taught their own insignificance and almost inutility. These remarks may seem an example of shutting the door after the steed is stolen; but if the plan proposed widely differs from that pursued by our expedition, let it be remembered that we were pioneers in an unknown country, feeling our way through tribes and populations, the political relations of which were at that time as little known as were the physical difficulties of the route we had been commissioned to explore through their midst.

These observations are the result of the experience gained in the course of this first attempt, and the opinions then formed have been confirmed on a more recent occasion, when it was not in my power to make any practical application of the knowledge of the ways and habits of the mountaineers which had been formerly gained.

If the reader is somewhat tired of the Kakhyens, he can better understand the wearisome and anxious time passed by us at Ponsee, as all through April we alternately hoped and despaired of escaping from our open-air prison. At the end of that time our party was reduced in numbers by the departure of Williams and Stewart, who acted upon the circular already mentioned as issued by the leader of the mission. They started, under the guidance of Moung Mo, on April 29th, and reached Bhamô without delay or difficulty.