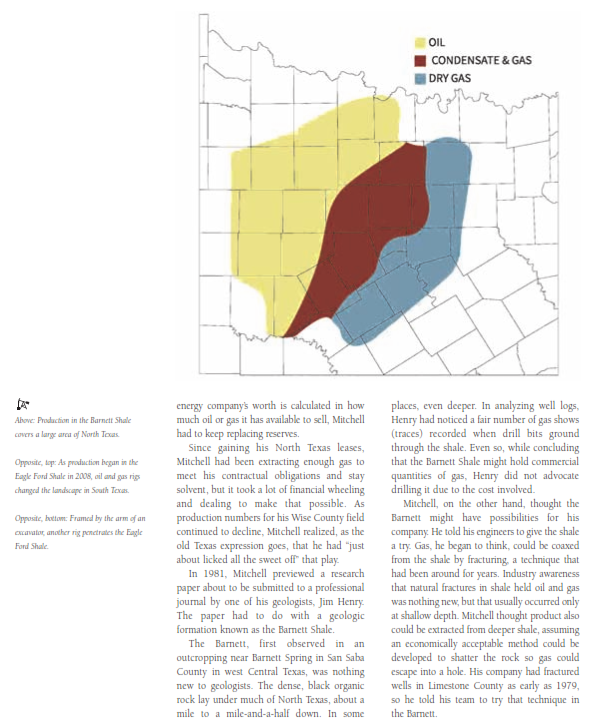

CHAPTER 1 1

UNCONVENTIONAL THINKING: SHALE PRODUCTION

When word began to spread about the amount of gas blowing out of one of Mitchell Energy's new wells in Wise County, executives and geologists with other companies in the competitive, but mostly cordial, Texas oil industry didn't believe what they were hearing. Old George Mitchell apparently had decided to play a practical joke on some of his fellow Texas oil men.

But the numbers were real. The news from North Texas, coming when just about everyone believed the once oil- and gas-rich Lone Star State's figurative fuel tank was slowly but steadily headed toward "empty," presaged a one-two punch of booms that would be equal to or greater than the 1901 Spindletop gusher that began the age of oil in Texas. Even the discovery of the storied East Texas oil field, the so-called Black Giant that came to life in 1930, was not as significant as what had transpired in Wise County.

Of course, as with many momentous changes, it took a while for the oil industry, not to mention Texas and the nation in general, to grasp the significance of what had happened that summer day in 1998. The innovation in unconventional production techniques, overseen by Mitchell, proved to be a Super Bowl-level game changer for Texas, the U.S. and the world. But it all started long before that prolific gas well came in near the close of the 20th century.

Later nominated for a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Galveston-born son of a Greek immigrant revolutionized the industry. Mitchell majored in petroleum engineering at Texas A&M University, graduating as class valedictorian in 1940, a year before the U.S. entered World War II. Following his military service in the Army Corps of Engineers, Mitchell got hired by Amoco, spending most of his time working on rigs in the swamps of Louisiana, learning the oil business the greasy, hands-on way. But he never forgot what one of his professors at A&M had told him: "If you want to drive a Chevrolet, work for a big oil company, but if you want to drive a Cadillac be an independent."

It did not take Mitchell long to decide he'd prefer a Cadillac over a Chevy, so in 1946 he and his older brother Johnny formed their own company in Houston. Having worked on rigs, Mitchell had both an engineering and scientific understanding of the energy business. And he would continue learning and studying, often staying up most of the night pouring over photostatic copies of drillings logs, hoping to find a geologic pattern others had missed.

The thirty-something oilman's level of success changed from okay to a lot better on the basis of a tip he got from a Chicago bookie in 1952. But the Windy City gambler wasn't touting a hot thoroughbred. Over coffee at a downtown Houston drug store in the building where Mitchell had an office, the bookie told Mitchell about a ranch in North Texas that might have good potential for gas. It turned out that someone Mitchell had known at A&M had been shopping the deal around for at least two years, but Mitchell didn't know that at first.

Mitchell reviewed the property's known geology and decided the bookmaker, who of course wanted some of the action, just might have spotted a sure bet. He leased 6,000 acres on the David J. Hughes Ranch in Wise County and soon brought in a substantial gas well. Quickly and quietly, he leased an additional 300,000 acres-an area about a third of the size of the sprawling King Ranch in South Texas-at $3 an acre.

His company went on to develop what at first seemed to be a robust gas field, but by the late 1970s Mitchell and his colleagues began to notice an ominous if slow decline in production. That was a big problem, because since the mid-1950s Mitchell had held a very lucrative contract to supply 100 million cubic feet of natural gas daily for Chicago, the nation's second-largest city. To stay in business, his company would have to meet that demand every year of the contract. On top of that, since an