CHAPTER III

GEOGRAPHY IN THE DARK AGES

We have seen how, by a slow process of conquest and expansion, the ancient world got to know a large part of the Eastern Hemisphere, and how this knowledge was summed up in the great work of Claudius Ptolemy. We have now to learn how much of this knowledge was lost or perverted—how geography, for a time, lost the character of a science, and became once more the subject of mythical fancies similar to those which we found in its earliest stages. Instead of knowledge which, if not quite exact, was at any rate approximately measured, the mediæval teachers who concerned themselves with the configuration of the inhabited world substituted their own ideas of what ought to be.[1] This is a process which applies not alone to geography, but to all branches of knowledge, which, after the fall of the Roman Empire, ceased to expand or progress, became mixed up with fanciful notions, and only recovered when a knowledge of ancient science and thought was restored in the fifteenth century. But in geography we can more easily see than in other sciences the exact nature of the disturbing influence which prevented the acquisition of new knowledge.

[Footnote 1: It is fair to add that Professor Miller's researches have shown that some of the "unscientific" qualities of the mediæval mappœ mundi were due to Roman models.]

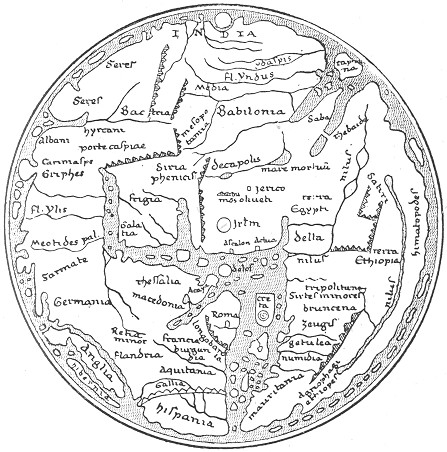

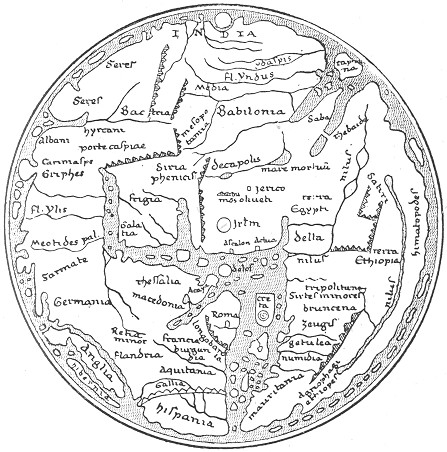

Briefly put, that disturbing influence was religion, or rather theology; not, of course, religion in the proper sense of the word, or theology based on critical principles, but theological conceptions deduced from a slavish adherence to texts of Scripture, very often seriously misunderstood. To quote a single example: when it is said in Ezekiel v. S, "This is Jerusalem: I have set it in the midst of the nations... round about her," this was not taken by the mediæval monks, who were the chief geographers of the period, as a poetical statement, but as an exact mathematical law, which determined the form which all mediæval maps took. Roughly speaking, of course, there was a certain amount of truth in the statement, since Jerusalem would be about the centre of the world as known to the ancients—at least, measured from east to west; but, at the same time, the mediæval geographers adopted the old Homeric idea of the ocean surrounding the habitable world, though at times there was a tendency to keep more closely to the words of Scripture about the four corners of the earth. Still, as a rule, the orthodox conception of the world was that of a circle enclosing a sort of T square, the east being placed at the top, Jerusalem in the centre; the Mediterranean Sea naturally divided the lower half of the circle, while the Ægean and Red Seas were regarded as spreading out right and left perpendicularly, thus dividing the top part of the world, or Asia, from the lower part, divided equally between Europe on the left and Africa on the right. The size of the Mediterranean Sea, it will be seen, thus determined the dimensions of the three continents. One of the chief errors to which this led was to cut off the whole of the south of Africa, which rendered it seemingly a short voyage round that continent on the way to India. As we shall see, this error had important and favourable results on geographical discovery.

GEOGRAPHICAL MONSTERS

Another result of this conception of the world as a T within an O, was to expand Asia to an enormous extent; and as this was a part of the world which was less known to the monkish map- makers of the Middle Ages, they were obliged to fill out their ignorance by their imagination. Hence they located in Asia all the legends which they had derived either from Biblical or classical sources. Thus there was a conception, for which very little basis is to be found in the Bible, of two fierce nations named Gog and Magog, who would one day bring about the destruction of the civilised world. These were located in what would have been Siberia, and it was thought that Alexander the Great had penned them in behind the Iron Mountains. When the great Tartar invasion came in the thirteenth century, it was natural to suppose that these were no less than the Gog and Magog of legend. So, too, the position of Paradise was fixed in the extreme east, or, in other words, at the top of mediæval maps. Then, again, some of the classical authorities, as Pliny and Solinus, had admitted into their geographical accounts legends of strange tribes of monstrous men, strangely different from normal humanity. Among these may be mentioned the Sciapodes, or men whose feet were so large that when it was hot they could rest on their backs and lie in the shade. There is a dim remembrance of these monstrosities in Shakespeare's reference to

"The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads

Do grow beneath their shoulders."

In the mythical travels of Sir John Maundeville there are illustrations of these curious beings, one of which is here reproduced. Other tracts of country were supposed to be inhabited by equally monstrous animals. Illustrations of most of these were utilised to fill up the many vacant spaces in the mediæval maps of Asia.

One author, indeed, in his theological zeal, went much further in modifying the conceptions of the habitable world. A Christian merchant named Cosmas, who had journeyed to India, and was accordingly known as COSMAS INDICOPLEUSTES, wrote, about 540 A.D., a work entitled "Christian Topography," to confound what he thought to be the erroneous views of Pagan authorities about the configuration of the world. What especially roused his ire was the conception of the spherical form of the earth, and of the Antipodes, or men who could stand upside down. He drew a picture of a round ball, with four men standing upon it, with their feet on opposite sides, and asked triumphantly how it was possible that all four could stand upright? In answer to those who asked him to explain how he could account for day and night if the sun did not go round the earth, he supposed that there was a huge mountain in the extreme north, round which the sun moved once in every twenty-four hours. Night was when the sun was going round the other side of the mountain. He also proved, entirely to his own satisfaction, that the sun, instead of being greater, was very much smaller than the earth. The earth was, according to him, a moderately sized plane, the inhabited parts of which were separated from the antediluvian world by the ocean, and at the four corners of the whole were the pillars which supported the heavens, so that the whole universe was something like a big glass exhibition case, on the top of which was the firmament, dividing the waters above and below it, according to the first chapter of Genesis.

THE HEREFORD MAP.

Cosmas' views, however interesting and amusing they are, were too extreme to gain much credence or attention even from the mediæval monks, and we find no reference to them in the various mappœ mundi which sum up their knowledge, or rather ignorance, about the world. One of the most remarkable of these maps exists in England at Hereford, and the plan of it given on p. 53 will convey as much information as to early mediæval geography as the ordinary reader will require. In the extreme east, i.e. at the top, is represented the Terrestrial Paradise; in the centre is Jerusalem; beneath this, the Mediterranean extends to the lower edge of the map, with its islands very carefully particularised. Much attention is given to the rivers throughout, but very little to the mountains. The only real increase of actual knowledge represented in the map is that of the north-east of Europe, which had I naturally become better known by the invasion of the Norsemen. But how little real knowledge was possessed of this portion of Europe is proved by the fact that the mapmaker placed near Norway the Cynocephali, or dog-headed men, probably derived from some confused accounts of Indian monkeys. Near them are placed the Gryphons, "men most wicked, for among their misdeeds they also make garments for themselves and their horses out of the skins of their enemies." Here, too, is placed the home of the Seven Sleepers, who lived for ever as a standing miracle to convert the heathen. The shape given to the British Islands will be observed as due to the necessity of keeping the circular form of the inhabited world. Other details about England we may leave for the present.

It is obvious that maps such as the Hereford one would be of no practical utility to travellers who desired to pass from one country to another; indeed, they were not intended for any such purpose. Geography had ceased to be in any sense a practical science; it only ministered to men's sense of wonder, and men studied it mainly in order to learn about the marvels of the world. When William of Wykeham drew up his rules for the Fellows and Scholars of New College, Oxford, he directed them in the long winter evenings to occupy themselves with "singing, or reciting poetry, or with the chronicles of the different kingdoms, or with the wonders of the world." Hence almost all mediæval maps are filled up with pictures of these wonders, which were the more necessary as so few people could read. A curious survival of this custom lasted on in map-drawing almost to the beginning of this century, when the spare places in the ocean were adorned with pictures of sailing ships or spouting sea monsters.

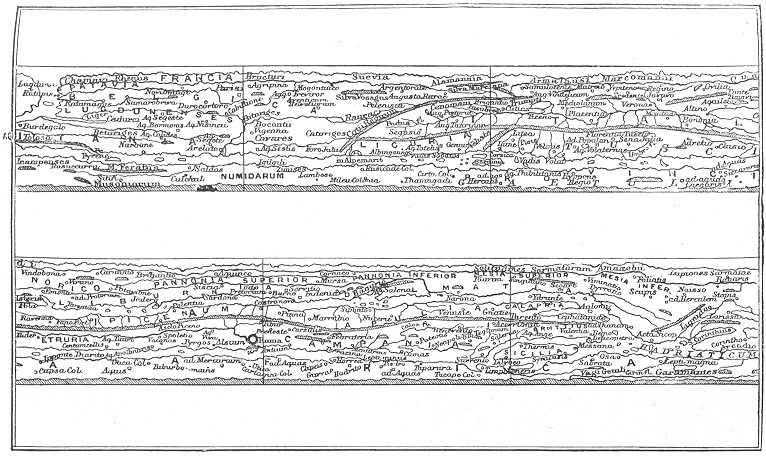

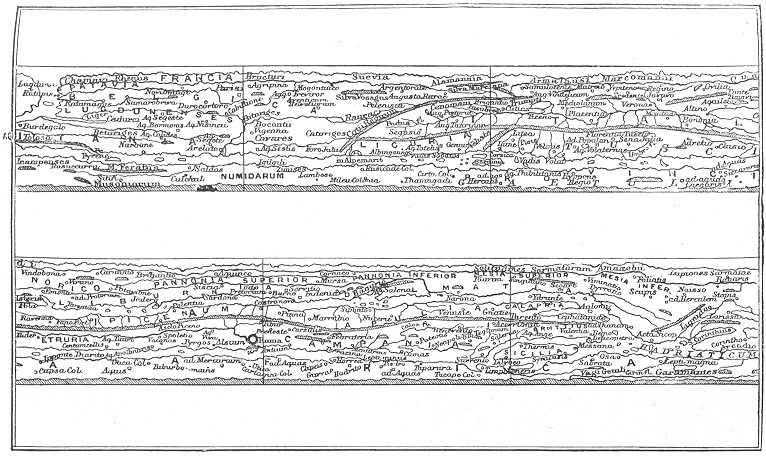

When men desired to travel, they did not use such maps as these, but rather itineraries, or road- books, which did not profess to give the shape of the countries through which a traveller would pass, but only indicated the chief towns on the most-frequented roads. This information was really derived from classical times, for the Roman emperors from time to time directed such road-books to be drawn up, and there still remains an almost complete itinerary of the Empire, known as the Peutinger Table, from the name of the German merchant who first drew the attention of the learned world to it. A condensed reproduction is given on the following page, from which it will be seen that no attempt is made to give anything more than the roads and towns. Unfortunately, the first section of the table, which started from Britain, has been mutilated, and we only get the Kentish coast. These itineraries were specially useful, as the chief journeys of men were in the nature of pilgrimages; but these often included a sort of commercial travelling, pilgrims often combining business and religion on their journeys. The chief information about Eastern Europe which reached the West was given by the succession of pilgrims who visited Palestine up to the time of the Crusades. Our chief knowledge of the geography of Europe daring the five centuries between 500 and 1000 A.D. is given in the reports of successive pilgrims.

THE PEUTINGER TABLE—WESTERN PART.

This period may be regarded as the Dark Age of geographical knowledge, during which wild conceptions like those contained in the Hereford map were substituted for the more accurate measurements of the ancients. Curiously enough, almost down to the time of Columbus the learned kept to these conceptions, instead of modifying them by the extra knowledge gained during the second period of the Middle Ages, when travellers of all kinds obtained much fuller information of Asia, North Europe, and even, as, we shall see, of some parts of America.

It is not altogether surprising that this period should have been so backward in geographical knowledge, since the map of Europe itself, in its political divisions, was entirely readjusted during this period. The thousand years of history which elapsed between 450 and 1450 were practically taken up by successive waves of invasion from the centre of Asia, which almost entirely broke up the older divisions of the world.

In the fifth century three wandering tribes, invaded the Empire, from the banks of the Vistula, the Dnieper, and the Volga respectively. The Huns came from the Volga, in the extreme east, and under Attila, "the Hammer of God," wrought consternation in the Empire; the Visigoths, from the Dnieper, attacked the Eastern Empire; while the Vandals, from the Vistula, took a triumphant course through Gaul and Spain, and founded for a time a Vandal empire in North Africa. One of the consequences of this movement was to drive several of the German tribes into France, Italy, and Spain, and even over into Britain; for it is from this stage in the world's history that we can trace the beginning of England, properly so called, just as the invasion of Gaul by the Franks at this time means the beginning of French history. By the eighth century the kingdom of the Franks extended all over France, and included most of Central Germany; while on Christmas Day, 800, Charles the Great was crowned at Rome, by the Pope, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, which professed to revive the glories of the old empire, but made a division between the temporal power held by the Emperor and the spiritual power held by the Pope.

One of the divisions of the Frankish Empire deserves attention, because upon its fate rested the destinies of most of the nations of Western Europe. The kingdom of Burgundy, the buffer state between France and Germany, has now entirely disappeared, except as the name of a wine; but having no natural boundaries, it was disputed between France and Germany for a long period, and it may be fairly said that the Franco-Prussian War was the last stage in its history up to the present. A similar state existed in the east of Europe, viz. the kingdom of Poland, which was equally indefinite in shape, and has equally formed a subject of dispute between the nations of Eastern Europe. This, as is well known, only disappeared as an independent state in 1795, when it finally ceased to act as a buffer between Russia and the rest of Europe. Roughly speaking, after the settlement of the Germanic tribes within the confines of the Empire, the history of Europe, and therefore its historical geography, may be summed up as a struggle for the possession of Burgundy and Poland.

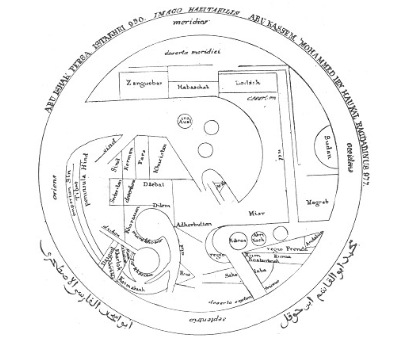

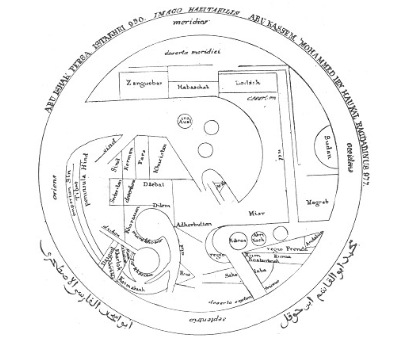

But there was an important interlude in the south-west of Europe, which must engage our attention as a symptom of a world-historic change in the condition of civilisation. During the course of the seventh and eighth centuries (roughly, between 622 and 750) the inhabitants of the Arabian peninsula burst the seclusion which they had held since the beginning, almost, of history, and, inspired by the zeal of the newly-founded religion of Islam, spread their influence from India to Spain, along the southern littoral of the Mediterranean. When they had once settled down, they began to recover the remnants of Græco-Roman science that had been lost on the north shores of the Mediterranean. The Christians of Syria used Greek for their sacred language, and accordingly when the Sultans of Bagdad desired to know something of the wisdom of the Greeks, they got Syriac-speaking Christians to translate some of the scientific works of the Greeks, first into Syriac, and thence into Arabic. In this way they obtained a knowledge of the great works of Ptolemy, both in astronomy—which they regarded as the more important, and therefore the greatest, Almagest—and also in geography, though one can easily understand the great modifications which the strange names of Ptolemy must have undergone in being transcribed, first into Syriac and then into Arabic. We shall see later on some of the results of the Arabic Ptolemy.

The conquests of the Arabs affected the knowledge of geography in a twofold way: by bringing about the Crusades, and by renewing the acquaintance of the west with the east of Asia. The Arabs were acquainted with South-Eastern Africa as far south as Zanzibar and Sofala, though, following the views of Ptolemy as to the Great Unknown South Land, they imagined that these spread out into the Indian Ocean towards India. They seem even to have had some vague knowledge of the sources of the Nile. They were also acquainted with Ceylon, Java, and Sumatra, and they were the first people to learn the various uses to which the cocoa-nut can be put. Their merchants, too, visited China as early as the ninth century, and we have from their accounts some of the earliest descriptions of the Chinese, who were described by them as a handsome people, superior in beauty to the Indians, with fine dark hair, regular features, and very like the Arabs. We shall see later on how comparatively easy it was for a Mohammedan to travel from one end of the known world to the other, owing to the community of religion throughout such a vast area.

Some words should perhaps be said on the geographical works of the Arabs. One of the most important of these, by Yacut, is in the form of a huge Gazetteer, arranged in alphabetical order; but the greatest geographical work of the Arabs is by EDRISI, geographer to King Roger of Sicily, 1154, who describes the world somewhat after the manner of Ptolemy, but with modifications of some interest. He divides the world into seven horizontal strips, known as "climates," and ranging from the equator to the British Isles. These strips are subdivided into eleven sections, so that the world, in Edrisi's conception, is like a chess-board, divided into seventy-seven squares, and his work consists of an elaborate description of each of these squares taken one by one, each climate being worked through regularly, so that you might get parts of France in the eighth and ninth squares, and other parts in the sixteenth and seventeenth. Such a method was not adapted to give a clear conception of separate countries, but this was scarcely Edrisi's object. When the Arabs—or, indeed, any of the ancient or mediæval writers—wanted wanted to describe a land, they wrote about the tribe or nation inhabiting it, and not about the position of the towns in it; in other words, they drew a marked distinction between ethnology and geography.

THE WORLD ACCORDING TO IBN HAUKAL.

But the geography of the Arabs had little or no influence upon that of Europe, which, so far as maps went, continued to be based on fancy instead of fact almost up to the time of Columbus.

Meanwhile another movement had been going on during the eighth and ninth centuries, which helped to make Europe what it is, and extended considerably the common knowledge of the northern European peoples. For the first time since the disappearance of the Phœnicians, a great naval power came into existence in Norway, and within a couple of centuries it had influenced almost the whole sea-coast of Europe. The Vikings, or Sea-Rovers, who kept their long ships in the viks, or fjords, of Norway, made vigorous attacks all along the coast of Europe, and in several cases formed stable governments, and so made, in a way, a sort of crust for Europe, preventing any further shaking of its human contents. In Iceland, in England, in Ireland, in Normandy, in Sicily, and at Constantinople (where they formed the Varangi, or body-guard of the Emperor), as well as in Russia, and for a time in the Holy Land, Vikings or Normans founded kingdoms between which there was a lively interchange of visits and knowledge.

They certainly extended their voyages to Greenland, and there is a good deal of evidence for believing that they travelled from Greenland to Labrador and Newfoundland. In the year 1001, an Icelander named Biorn, sailing to Greenland to visit his father, was driven to the south-west, and came to a country which they called Vinland, inhabited by dwarfs, and having a shortest day of eight hours, which would correspond roughly to 50° north latitude. The Norsemen settled there, and as late as 1121 the Bishop of Greenland visited them, in order to convert them to Christianity. There is little reason to doubt that this Vinland was on the mainland of North America, and the Norsemen were therefore the first Europeans to discover America. As late as 1380, two Venetians, named Zeno, visited Iceland, and reported that there was a tradition there of a land named Estotiland, a thousand miles west of the Faroe Islands, and south of Greenland. The people were reported to be civilised and good seamen, though unacquainted with the use of the compass, while south of them were savage cannibals, and still more to the south-west another civilised people, who built large cities and temples, but offered up human victims in them. There seems to be here a dim knowledge of the Mexicans.

The great difficulty in maritime discovery, both for the ancients and the men of the Middle Ages, was the necessity of keeping close to the shore. It is true they might guide themselves by the sun during the day, and by the pole-star at night, but if once the sky was overcast, they would become entirely at a loss for their bearings. Hence the discovery of the polar tendency of the magnetic needle was a necessary prelude to any extended voyages away from land. This appears to have been known to the Chinese from quite ancient times, and utilised on their junks as early as the eleventh century. The Arabs, who voyaged to Ceylon and Java, appear to have learnt its use from the Chinese, and it is probably from them that the mariners of Barcelona first introduced its use into Europe. The first mention of it is given in a treatise on Natural History by Alexander Neckam, foster-brother of Richard, Cœur de Lion. Another reference, in a satirical poem of the troubadour, Guyot of Provence (1190), states that mariners can steer to the north star without seeing it, by following the direction of a needle floating in a straw in a basin of water, after it had been touched by a magnet. But little use, however, seems to have been made of this, for Brunetto Latini, Dante's tutor, when on a visit to Roger Bacon in 1258, states that the friar had shown him the magnet and its properties, but adds that, however useful the discovery, "no master mariner would dare to use it, lest he should be thought to be a magician." Indeed, in the form in which it was first used it would be of little practical utility, and it was not till the method was found of balancing it on a pivot and fixing it on a card, as at present used, that it became a necessary part of a sailor's outfit. This practical improvement is attributed to one Flavio Gioja, of Amalfi, in the beginning of the fourteenth century.

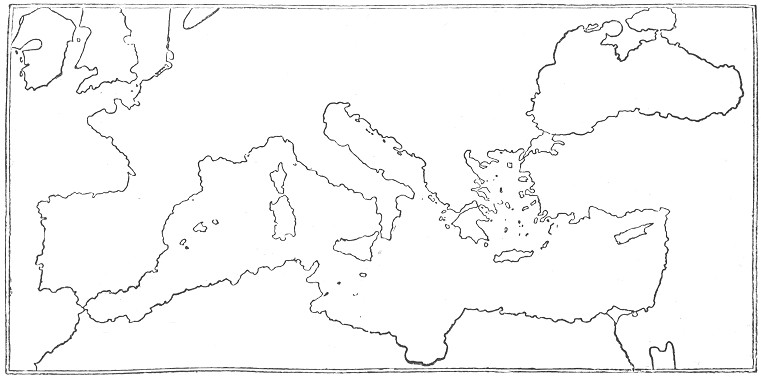

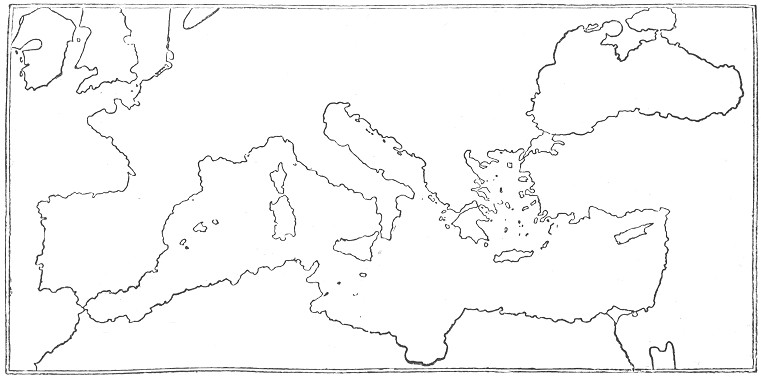

THE MEDITERRANEAN COAST IN THE PORTULANI.

When once the mariner's compass had come into general use, and its indications observed by master mariners in their voyages, a much more practical method was at hand for determining the relative positions of the different lands. Hitherto geographers (i.e., mainly the Greeks and Arabs) had had to depend for fixing relative positions on the vague statements in the itineraries of merchants and soldiers; but now, with the aid of the compass, it was not difficult to determine the relative position of one point to another, while all the windings of a road could be fixed down on paper without much difficulty. Consequently, while the learned monks were content with the mixture of myth and fable which we have seen to have formed the basis of their maps of the world, the seamen of the Mediterranean were gradually building up charts of that sea and the neighbouring lands which varied but little from the true position. A chart of this kind was called a Portulano, as giving information of the best routes from port to port, and Baron Nordenskiold has recently shown how all these portulani are derived from a single Catalan map which has been lost, but must have been compiled between 1266 and 1291. And yet there were some of the learned who were not above taking instruction from the practical knowledge of the seamen. In 1339, one Angelico Dulcert, of Majorca, made an elaborate map of the world on the principle of the portulano, giving the coast line—at least of the Mediterranean—with remarkable accuracy. A little later, in 1375, a Jew of the same island, named Cresquez, made an improvement on this by introducing into the eastern parts of the map the recently acquired knowledge of Cathay, or China, due to the great traveller Marco Polo. His map (generally known as the Catalan Map, from the language of the inscriptions plentifully scattered over it) is divided into eight horizontal strips, and on the preceding page will be found a reduced reproduction, showing how very accurately the coast line of the Mediterranean was reproduced in these portulanos.

With the portulanos, geographical knowledge once more came back to the lines of progress, by reverting to the representation of fact, and, by giving an accurate representation of the coast line, enabled mariners to adventure more fearlessly and to return more safely, while they gave the means for recording any further knowledge. As we shall see, they aided Prince Henry the Navigator to start that series of geographical investigation which led to the discoveries that close the Middle Ages. With them we may fairly close the history of mediæval geography, so far as it professed to be a systematic branch of knowledge.

We must now turn back and briefly sum up the additions to knowledge made by travellers, pilgrims, and merchants, and recorded in literary shape in the form of travels.

[Authorities: Lelewel, Géographie du Moyen Age, 4 vols. and atlas, 1852; C. R. Beazley, Dawn of Geography, 1897, and Introduction to Prince Henry the Navigator, 1895; Nordenskiold, Periplus, 1897.]