CHAPTER IV

MEDIÆVAL TRAVELS

In the Middle Ages—that is, in the thousand years between the irruption of the barbarians into the Roman Empire in the fifth century and the discovery of the New World in the fifteenth—the chief stages of history which affect the extension of men's knowledge of the world were: the voyages of the Vikings in the eighth and ninth centuries, to which we have already referred; the Crusades, in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; and the growth of the Mongol Empire in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The extra knowledge obtained by the Vikings did not penetrate to the rest of Europe; that brought by the Crusades, and their predecessors, the many pilgrimages to the Holy Land, only restored to Western Europe the knowledge already stored up in classical antiquity; but the effect of the extension of the Mongol Empire was of more wide-reaching importance, and resulted in the addition of knowledge about Eastern Asia which was not possessed by the Romans, and has only been surpassed in modern times during the present century.

Towards the beginning of the thirteenth century, Chinchiz Khan, leader of a small Tatar tribe, conquered most of Central and Eastern Asia, including China. Under his son, Okkodai, these Mongol Tatars turned from China to the West, conquered Armenia, and one of the Mongol generals, named Batu, ravaged South Russia and Poland, and captured Buda-Pest, 1241. It seemed as if the prophesied end of the world had come, and the mighty nations Gog and Magog had at last burst forth to fulfil the prophetic words. But Okkodai died suddenly, and these armies were recalled. Universal terror seized Europe, and the Pope, as the head of Christendom, determined to send ambassadors to the Great Khan, to ascertain his real intentions. He sent a friar named John of Planocarpini, from Lyons, in 1245, to the camp of Batu (on the Volga), who passed him on to the court of the Great Khan at Karakorum, the capital of his empire, of which only the slightest trace is now left on the left bank of the Orkhon, some hundred miles south of Lake Baikal.

Here, for the first time, they heard of a kingdom on the east coast of Asia which was not yet conquered by the Mongols, and which was known by the name of Cathay. Fuller information was obtained by another friar, named WILLIAM RUYSBROEK, or Rubruquis, a Fleming, who also visited Karakorum as an ambassador from St. Louis, and got back to Europe in 1255, and communicated some of his information to Roger Bacon. He says: "These Cathayans are little fellows, speaking much through the nose, and, as is general with all those Eastern people, their eyes are very narrow.... The common money of Cathay consists of pieces of cotton paper; about a palm in length and breadth, upon which certain lines are printed, resembling the seal of Mangou Khan. They do their writing with a pencil such as painters paint with, and a single character of theirs comprehends several letters, so as to form a whole word." He also identifies these Cathayans with the Seres of the ancients. Ptolemy knew of these as possessing the land where the silk comes from, but he had also heard of the Sinæ, and failed to identify the two. It has been conjectured that the name of China came to the West by the sea voyage, and is a Malay modification, while the names Seres and Cathayans came overland, and thus caused confusion.

Other Franciscans followed these, and one of them, John of Montecorvino, settled at Khanbalig (imperial city), or Pekin, as Archbishop (ob. 1358); while Friar Odoric of Pordenone, near Friuli, travelled in India and China between 1316 and 1330, and brought back an account of his voyage, filled with most marvellous mendacities, most of which were taken over bodily into the work attributed to Sir John Maundeville.

The information brought back by these wandering friars fades, however, into insignificance before the extensive and accurate knowledge of almost the whole of Eastern Asia brought back to Europe by Marco Polo, a Venetian, who spent eighteen years of his life in the East. His travels form an epoch in the history of geographical discovery only second to the voyages of Columbus.

In 1260, two of his uncles, named Nicolo and Maffeo Polo, started from Constaninople on a trading venture to the Crimea, after which they were led to visit Bokhara, and thence on to the court of the Great Khan, Kublai, who received them very graciously, and being impressed with the desirability of introducing Western civilisation into the new Mongolian empire, he entrusted them with a message to the Pope, demanding one hundred wise men of the West to teach the Mongolians the Christian religion and Western arts. The two brothers returned to their native place, Venice, in 1269, but found no Pope to comply with the Great Khan's request; for Clement IV. had died the year before, and his successor had not yet been appointed. They waited about for a couple of years till Gregory X. was elected, but he only meagrely responded to the Great Khan's demands, and instructed two Dominicans to accompany the Polos, who on this occasion took with them their young nephew Marco, a lad of seventeen. They started in November 1271, but soon lost the company of the Dominicans, who lost heart and went back.

They went first to Ormuz, at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, then struck northward through Khorasan Balkh to the Oxus, and thence on to the Plateau of Pomir. Thence they passed the Great Desert of Gobi, and at last reached Kublai in May 1275, at his summer residence in Kaipingfu. Notwithstanding that they had not carried out his request, the Khan received them in a friendly manner, and was especially taken by Marco, whom he took into his own service; and quite recently a record has been found in the Chinese annals, stating that in the year 1277 a certain Polo was nominated a Second- Class Commissioner of the PrivyCouncil. His duty was to travel on various missions to Eastern Tibet, to Cochin China, and even to India. The Polos amassed much wealth owing to the Khan's favour, but found him very unwilling to let them return to Europe. Marco Polo held several important posts; for three years he was Governor of the great city of Yanchau, and it seemed likely that he would die in the service of Kublai Khan.

But, owing to a fortunate chance, they were at last enabled to get back to Europe. The Khan of Persia desired to marry a princess of the Great Khan's family, to whom he was related, and as the young lady upon whom the choice fell could not be expected to undergo the hardships of the overland journey from China to Persia, it was decided to send her by sea round the coast of Asia. The Tatars were riot good navigators, and the Polos at last obtained permission to escort the young princess on the rather perilous voyage. They started in 1292, from Zayton, a port in Fokien, and after a voyage of over two years round the South coast of Asia, successfully carried the lady to her destined home, though she ultimately had to marry the son instead of the father, who had died in the interim. They took leave of her, and travelled through Persia to their own place, which they reached in 1295. When they arrived at the ancestral mansion of the Polos, in their coarse dress of Tatar cut, their relatives for some time refused to believe that they were really the long-lost merchants. But the Polos invited them to a banquet, in which they dressed themselves all in their best, and put on new suits for every course, giving the clothes they had taken off to the servants. At the conclusion of the banquet they brought forth the shabby dresses in which they had first arrived, and taking sharp knives, began to rip up the seams, from which they took vast quantities of rubies, sapphires, carbuncles, diamonds, and emeralds, into which form they had converted most of their property. This exhibition naturally changed the character of the welcome they received from their relatives, who were then eager to learn how they had come by such riches.

In describing the wealth of the Great Khan, Marco Polo, who was the chief spokesman of the party, was obliged to use the numeral "million" to express the amount of his wealth and the number of the population over whom he ruled. This was regarded as part of the usual travellers' tales, and Marco Polo was generally known by his friends as "Messer Marco Millione."

Such a reception of his stories was no great encouragement to Marco to tell the tale of his remarkable travels, but in the year of his arrival at Venice a war broke out between Genoa and the Queen of the Adriatic, in which Marco Polo was captured and cast into prison at Genoa. There he found as a fellow-prisoner one Rusticano of Pisa, a man of some learning and a sort of predecessor of Sir Thomas Malory, since he had devoted much time to re-writing, in prose, abstracts of the many romances relating to the Round Table. These he wrote, not in Italian (which can scarcely be said to have existed for literary purposes in those days), but in French, the common language of chivalry throughout Western Europe. While in prison with Marco Polo, he took down in French the narrative of the great traveller, and thus preserved it for all time. Marco Polo was released in 1299, and returned to Venice, where he died some time after 9th January 1334, the date of his will.

Of the travels thus detailed in Marco Polo's book, and of their importance and significance in the history of geographical discovery, it is impossible to give any adequate account in this place. It will, perhaps, suffice if we give the summary of his claims made out by Colonel Sir Henry Yule, whose edition of his travels is one of the great monuments of English learning:—

"He was the first traveller to trace a route across the whole longitude of Asia, naming and describing kingdom after kingdom which he had seen with his own eyes: the deserts of Persia, the flowering plateaux and wild gorges of Badakhshan, the jade-bearing rivers of Khotan, the Mongolian Steppes, cradle of the power that had so lately threatened to swallow up Christendom, the new and brilliant court that had been established by Cambaluc; the first traveller to reveal China in all its wealth and vastness, its mighty rivers, its huge cities, its rich manufactures, its swarming population, the inconceivably vast fleets that quickened its seas and its inland waters; to tell us of the nations on its borders, with all their eccentricities of manners and worship; of Tibet, with its sordid devotees; of Burma, with its golden pagodas and their tinkling crowns; of Laos, of Siam, of Cochin China, of Japan, the Eastern Thule, with its rosy pearls and golden-roofed palaces; the first to speak of that museum of beauty and wonder, still so imperfectly ransacked, the Indian Archipelago, source of those aromatics then so highly prized, and whose origin was so dark; of Java, the pearl of islands; of Sumatra, with its many kings, its strange costly products, and its cannibal races; of the naked savages of Nicobar and Andaman; of Ceylon, the island of gems, with its sacred mountain, and its tomb of Adam; of India the Great, not as a dreamland of Alexandrian fables, but as a country seen and personally explored, with its virtuous Brahmans, its obscene ascetics, its diamonds, and the strange tales of their acquisition, its sea-beds of pearl, and its powerful sun: the first in mediæval times to give any distinct account of the secluded Christian empire of Abyssinia, and the semi-Christian island of Socotra; to speak, though indeed dimly, of Zanzibar, with its negroes and its ivory, and of the vast and distant Madagascar, bordering on the dark ocean of the South, with its Ruc and other monstrosities, and, in a remotely opposite region, of Siberia and the Arctic Ocean, of dog-sledges, white bears, and reindeer-riding Tunguses."

Marco Polo's is thus one of the greatest names in the history of geography; it may, indeed, be doubted whether any other traveller has ever added so extensively to our detailed knowledge of the earth's surface. Certainly up to the time of Mr. Stanley no man had on land visited so many places previously unknown to civilised Europe. But the lands he discovered, though already fully populated, were soon to fall into disorder, and to be closed to any civilising influences. Nothing for a long time followed from these discoveries, and indeed almost up to the present day his accounts were received with incredulity, and he himself was regarded more as "Marco Millione" than as Marco Polo.

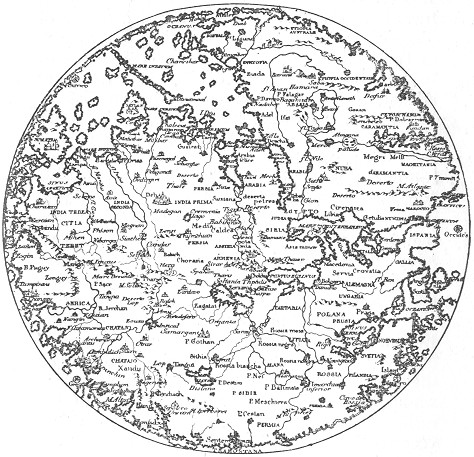

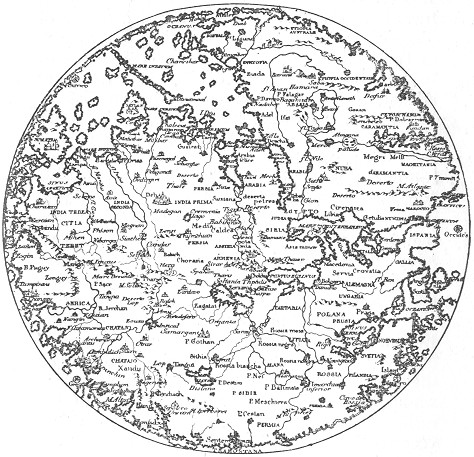

FRA MAURO'S MAP, 1457.

Extensive as were Marco Polo's travels, they were yet exceeded in extent, though not in variety, by those of the greatest of Arabian travellers, Mohammed Ibn Batuta, a native of Tangier, who began his travels in 1334, as part of the ordinary duty of a good Mohammedan to visit the holy city of Mecca. While at Alexandria he met a learned sage named Borhan Eddin, to whom he expressed his desire to travel. Borhan said to him, "You must then visit my brother Farid Iddin and my brother Rokn Eddin in Scindia, and my brother Borhan Eddin in China. When you see them, present my compliments to them." Owing mainly to the fact that the Tatar princes had adopted Islamism instead of Christianity, after the failure of Gregory X. to send Christian teachers to China, Ibn Batuta was ultimately enabled to greet all three brothers of Borhan Eddin. Indeed, he performed a more extraordinary exploit, for he was enabled to convey the greetings of the Sheikh Kawan Eddin, whom he met in China, to a relative of his residing in the Soudan. During the thirty years of his travels he visited the Holy Land, Armenia, the Crimea, Constantinople (which he visited in company with a Greek princess, who married one of the Tatar Khans), Bokhara, Afghanistan, and Delhi. Here he found favour with the emperor Mohammed Inghlak, who appointed him a judge, and sent him on an embassy to China, at first overland, but, as this was found too dangerous a route, he went ultimately from Calicut, via Ceylon, the Maldives, and Sumatra, to Zaitun, then the great port of China. Civil war having broken out, he returned by the same route to Calicut, but dared not face the emperor, and went on to Ormuz and Mecca, and returned to Tangier in 1349. But even then his taste for travel had not been exhausted. He soon set out for Spain, and worked his way through Morocco, across the Sahara, to the Soudan. He travelled along the Niger (which he took for the Nile), and visited Timbuctoo. He ultimately returned to Fez in 1353, twenty-eight years after he had set out on his travels. Their chief interest is in showing the wide extent of Islam in his day, and the facilities which a common creed gave for extensive travel. But the account of his journeys was written in Arabic, and had no influence on European knowledge, which, indeed, had little to learn from him after Marco Polo, except with regard to the Soudan. With him the history of mediæval geography may be fairly said to end, for within eighty years of his death began the activity of Prince Henry the Navigator, with whom the modern epoch begins.

Meanwhile India had become somewhat better known, chiefly by the travels of wandering friars, who visited it mainly for the sake of the shrine of St. Thomas, who was supposed to have been martyred in India. Mention should also be made of the early spread of the Nestorian Church throughout Central Asia. As early as the seventh century the Syrian Christians who followed the views of Nestorius began spreading them eastward, founding sees in Persia and Turkestan, and ultimately spreading as far as Pekin. There was a certain revival of their missionary activity under the Mongol Khans, but the restricted nature of the language in which their reports were written prevented them from having any effect upon geographical knowledge, except in one particular, which is of some interest. The fate of the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel has always excited interest, and a legend arose that they had been converted to Christianity, and existed somewhere in the East under a king who was also a priest, and known as Prester John. Now, in the reports brought by some of the Nestorian priests westward, it was stated that one of the Mongol princes named Ung Khan had adopted Christianity, and as this in Syriac sounded something like "John the Cohen," or "Priest," he was identified with the Prester John of legend, and for a long time one of the objects of travel in the East was to discover this Christian kingdom. It was, however, later ascertained that there did exist such a Christian kingdom in Abyssinia, and as owing to the erroneous views of Ptolemy, followed by the Arabs, Abyssinia was considered to spread towards Farther India, the land of Prester John was identified in Abyssinia. We shall see later on how this error helped the progress of geographical discovery.

The total addition of these mediæval travels to geographical knowledge consisted mainly in the addition of a wider extent of land in China, and the archipelago of Japan, or Cipangu, to the map of the world. The accompanying map displays the various travels and voyages of importance, and will enable the reader to understand how students of geography, who added on to Ptolemy's estimate of the extent of the world east and west the new knowledge acquired by Marco Polo, would still further decrease the distance westward between Europe and Cipangu, and thus prepare men for the voyage of Columbus.

[Authorities: Sir Henry Yule, Cathay and the Way Thither, 1865; The Book of Ser Marco Polo, 1875.]