CHAPTER XI

DANA, AS MITCHELL SAW HIM

A Picture of the Room Where One Man Ruled for Thirty Years.—The Democratic Ways of a Newspaper Autocrat.—W. O. Bartlett, Pike, and His Other Early Associates.

THE English historian, Kinglake, wrote a description of John T. Delane, the most famous editor of the London Times, which Mr. Dana’s associate, Mr. Mitchell, liked to quote as a picture of what Mr. Dana was not. It is a fine limning of the great editor, as great editors were supposed to be before Dana showed his disregard for the journalistic dust of the ages:

From the moment of his entering the editor’s room until four or five o’clock in the morning, the strain he had to put on his faculties must have been always great, and in stirring times almost prodigious. There were hours of night when he often had to decide—to decide, of course, with great swiftness—between two or more courses of action momentously different; when, besides, he must judge the appeals brought up to the paramount arbiter from all kinds of men, from all sorts of earthly tribunals; when despatches of moment, when telegrams fraught with grave tidings, when notes hastily scribbled in the Lords or Commons, were from time to time coming in to disturb, perhaps even to annul, former reckonings; and these, besides, were the hours when, on questions newly obtruding, yet so closely, so importunately, present that they would have to be met before sunrise, he somehow must cause to spring up sudden essays, invectives, and arguments which only strong power of brain, with even much toil, could supply. For the delicate task any other than he would require to be in a state of tranquillity, would require to have ample time. But for him there are no such indulgences; he sees the hand of the clock growing more and more peremptory, and the time drawing nearer and nearer when his paper must, must be made up.

That, mark you, was Delane, not Dana. When Mr. Dana counselled the young men at Cornell never to be in a hurry, he meant it. Fury was never a part of his system of life and work. Probably he viewed with something like contempt the high-pressure editor of his own and former days. There was no agony in the daily birth of the Sun. Mr. Mitchell said of his chief:

Mr. Dana has always been the master, and not the slave, of the immediate task. The external features of his journalism are simplicity, directness, common sense, and the entire absence of affectation. He would no more think of living up to Mr. Kinglake’s ideal of a great, mysterious, and thought-burdened editor, than of putting on a conical hat and a black robe spangled with suns, moons, and stars, when about to receive a visitor to his editorial office in Nassau Street.

That office in Nassau Street, of which every reader of the Sun, and surely every newspaperman in America, formed his own mental picture! To some imaginations it probably was a bare room, with a desk for the editor and, close by, the famous cat. To other imaginations, whose owners were familiar with Mr. Dana’s love for the beautiful, the office may have been a studio unmarred by the presence of a single unbeautiful object. Both visions were incorrect.

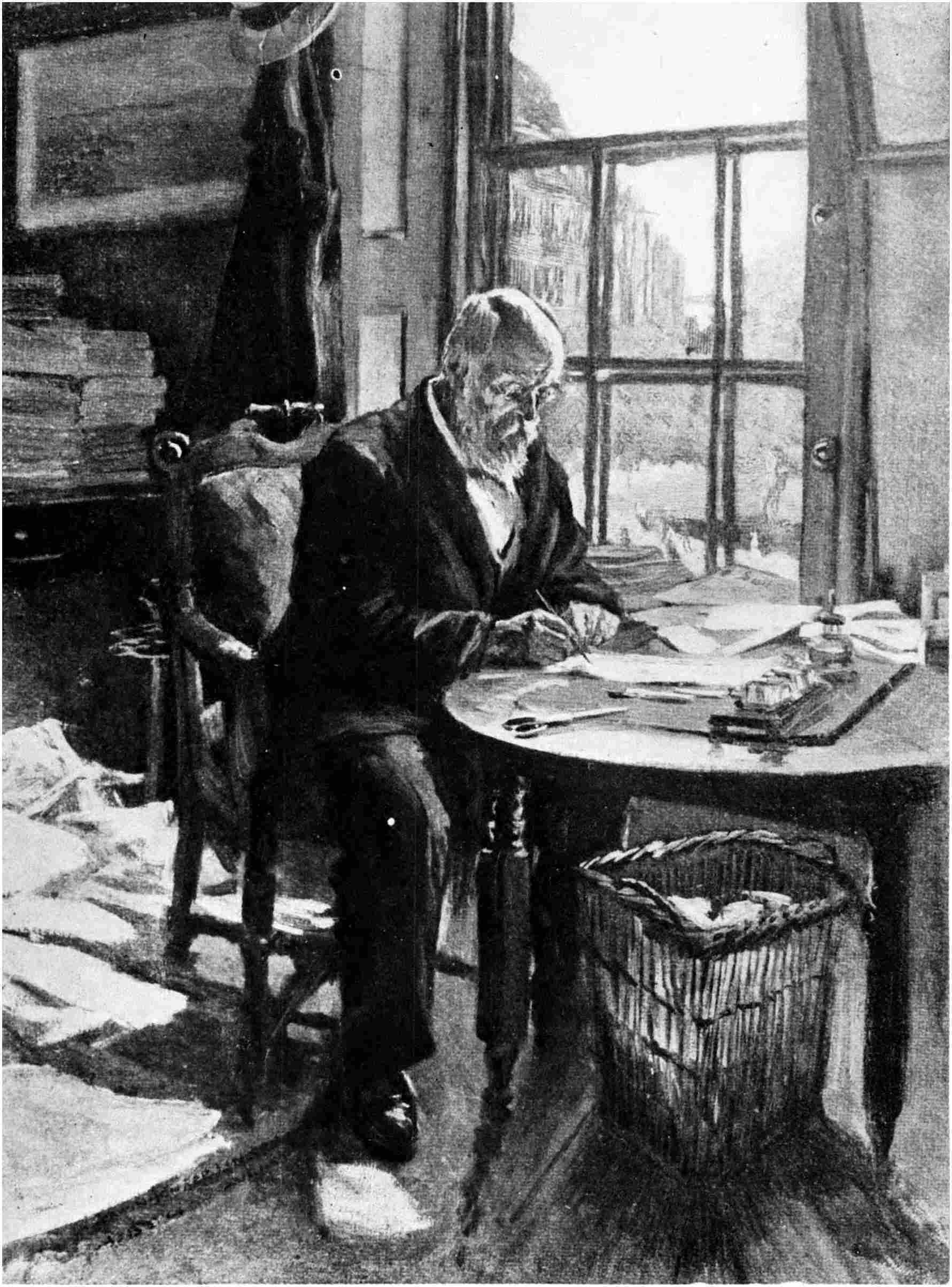

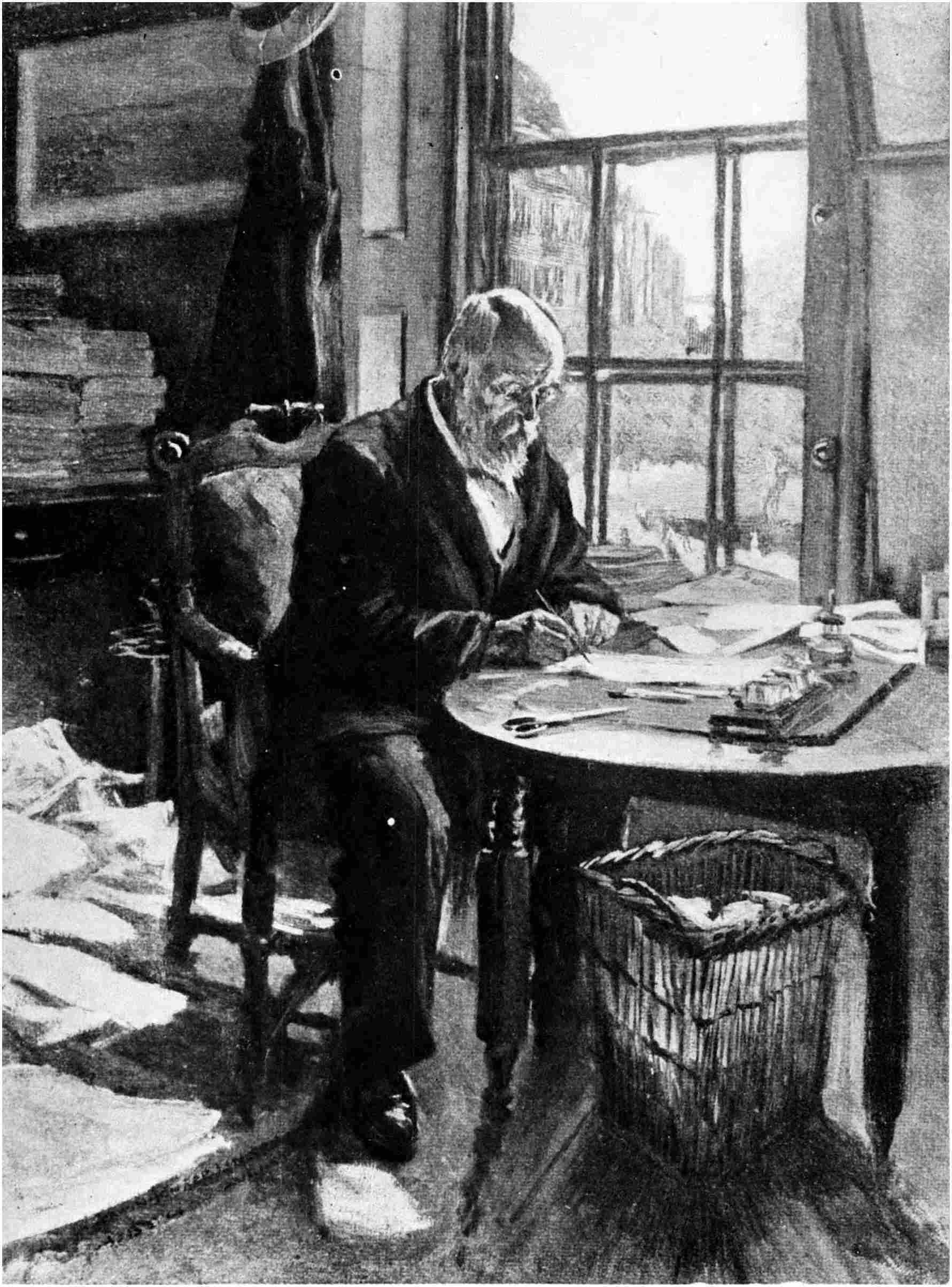

(Drawn from Life by Corwin Knapp Linson)

MR. DANA IN HIS OFFICE

Surroundings were nothing to Dana. To him an office was a place to work, to convert ideas into readable form. What would works of art be in such a place to a man who took more interest in the crowds that went to and fro on Park Row beneath his window? Let the room itself be described by Mr. Mitchell, who set down this picture of it after he had spent hours in it with Mr. Dana almost daily for twenty years:

In the middle of the small room a desk-table of black walnut of the Fulton Street style and the period of the first administration of Grant; a shabby little round table at the window, where Mr. Dana sits when the day is dark; one leather-covered chair, which does duty at either post, and two wooden chairs, both rickety, for visitors on errands of business or ceremony; on the desk a revolving case with a few dozen books of reference; an ink-pot and pen, not much used except in correcting manuscript and proofs, for Mr. Dana talks off to a stenographer his editorial articles and his correspondence, sometimes spending on the revision of the former twice as much time as was required for the dictation; a window-seat filled with exchanges, marked here and there in blue pencil for the editor’s eyes; a big pair of shears, and two or three extra pairs of spectacles in cache against an emergency—these few items constitute what is practically the whole objective equipment of the editor of the Sun. The shears are probably the newest article of furniture in the list. They replaced, three or four years ago, another pair of unknown antiquity, besought and obtained by Eugene Field, and now occupying, alongside of Mr. Gladstone’s ax, the place of honor in that poet’s celebrated collection of edged instruments.

For the non-essentials, the little trapezoid-shaped room contains a third table containing a file of the newspaper for a few weeks back, and a heap of new books which have passed review; an iron umbrella-rack; on the floor a cheap Turkish rug; and a lounge covered with horsehide, upon which Mr. Dana descends for a five minutes’ nap perhaps five times a year.

The adornments of the room are mostly accidental and insignificant. Ages ago somebody presented to Mr. Dana, with symbolic intent, a large stuffed owl. The bird of wisdom remains by inertia on top of the revolving bookcase, just as it would have remained there if it had been a stuffed cat or a statuette of “Folly.” Unnoticed and probably long ago forgotten by the proprietor, the owl solemnly boxes the compass as Mr. Dana swings the case, reaching in quick succession for his Bible, his Portuguese dictionary, his compendium of botanical terms, or his copy of the Democratic national platform of 1892. On the mantelpiece is an ugly, feather-haired little totem figure from Alaska, which likewise keeps its place solely by possession. It stands between a photograph of Chester A. Arthur, whom Mr. Dana liked and admired as a man of the world, and the japanned calendar-case which has shown him the time of year for the last quarter of a century. A dingy chromolithograph of Prince von Bismarck stands shoulder to shoulder with George, the Count Joannes.

The same mingling of sentiment and pure accident marks the rest of Mr. Dana’s picture-gallery. There is a large and excellent photograph of Horace Greeley, who is held in half-affectionate, half-humorous remembrance by his old associate in the management of the Tribune. Another is of the late Justice Blatchford, of the United States Supreme Court; it is the strong face of the fearless judge whose decision from the Federal bench in New York twenty years ago blocked the attempt to drag Mr. Dana before a servile little court in Washington to be tried without a jury on the charge of criminal libel, at the time when the Sun was demolishing the District Ring.

Over the mantel is Abraham Lincoln. There are pictures of the four Harper brothers and of the Appletons. Andrew Jackson is there twice, once in black and white, once in vivid colors. An inexpensive Thomas Jefferson faces the livelier Jackson. A framed diploma certifies that Mr. Dana was one of several gentlemen who presented to the State a portrait in oils of Samuel J. Tilden. On different sides of the room are William T. Coleman, the organizer of the San Francisco Vigilantes, and a crude colored print of the Haifa colony at the foot of Mount Carmel in Syria. Strangest of all in this singular collection is a photograph of a tall, lank, and superior-looking New England mill-girl, issued as an advertisement by some Connecticut concern engaged in the manufacture of spool-cotton.

For a good many years the most available wall-space in Mr. Dana’s office was occupied by a huge pasteboard chart, showing elaborately, in deadly parallel columns, the differences in the laws of the several States of the Union respecting divorce. It was put there, and it remained there, serving no earthly purpose except to illustrate the editor’s indifference as to his immediate surroundings, until it disappeared as mysteriously as it had come.

Such were Mr. Dana’s surroundings, with nothing to indicate, as Mr. Mitchell remarked, that the occupant “knew Manet from Monet, or old Persian lustre from Gubbio.”

It is twenty years since Dana went out of that room for the last time, and the room and the old building are no more, but the stuffed owl is still at his post in the office of the editor of the Sun. He is an older if not wiser bird, and he is no longer subjected to the revolutions of the bookcase, for Mr. Mitchell has given him a firmer perch beside his door. From a nearby wall Mr. Dana’s pictures of the four Harpers keep vigil, too.

Dana was interested in everything, read everything, saw almost everybody. His own office was almost as free as the great main office of the Sun, where sat everybody from the managing editor down to the office-boy. One day Dana, coming into the big room, saw carpenters building a partition between the room and the head of the stairs that led to the street. It was explained to him that the public was inclined to be unnecessarily intrusive at times.

“Take the partition down,” he said. “A newspaper is for the public.”

That this was not always a desirable plan is illustrated in a story about Dana, probably apocryphal, but characteristic. One night the city editor rushed into his chief’s room.

“Mr. Dana,” he said, “there’s a man out there with a cocked revolver. He is very much excited, and he insists on seeing the editor-in-chief.”

“Is he very much excited?” inquired Mr. Dana, returning to the proof that he was reading. “If you think it is worth while, ask Amos Cummings if he will see the gentleman and write him up.”

Persons in search of alms would enter Mr. Dana’s room without ceremony. If they were Sisters of Charity, as often was the case, Mr. Dana would walk up and down, telling them of his visit with the Pope, and would finish by giving them one of the silver dollars of which his pocket seemed to have an endless supply. Almost every day, when he despatched a boy to a nearby restaurant for his sandwich and bottle of milk, he would give him a five-dollar bill and instruct him to bring back the change all in silver. He liked to jingle the coins in his pocket and to have them ready for alms-giving.

Dana was never fussy, never overbearing with his men. He bore patiently with the occasional sinner, and tried to put the best face on a mistake.

The Dana patience extended also to outsiders. On one occasion William M. Laffan, then the dramatic critic and later the owner of the Sun, wrote a severe criticism of a performance by Miss Ada Rehan. Augustin Daly hurried to Mr. Dana’s office the next afternoon.

“Mr. Dana,” he said, “I have called to try to convince you that you should discharge your dramatic editor. He has—”

“I see,” said Dana, smiling. “Well, Mr. Daly, I will speak to Mr. Laffan about the matter, and if he thinks that he really deserves to be discharged, I will most certainly do it!”

Thirty or forty years ago the belief was not uncommon, among those ignorant of editorial methods and the limitations of human powers, that Mr. Dana wrote every word that appeared on the editorial page of the Sun. It is likely that this flattering myth came to his ears and caused him more than one chuckle. Dana wrote pieces for the Sun, many of them, but he never essayed the superhuman task of filling the whole page with his own self. Nobody knew better than he what a bore a man becomes who flows opinion constantly, whether by voice or by pen.

For Dana, not the eternal verities in allopathic doses, but the entertaining varieties, carefully administered. He might be immensely interested in the destruction of the Whisky Ring, and in writing about that infamy articles which would scorch the ears of Washington; but he knew that not every man, woman, and child who read the Sun was furious about the Whisky Ring or cared to read columns of opinion about it every day. They must have pabulum in the form of an article about the princely earnings of Charles Dickens, or the identification of Mount Sinai, or the mysterious murder of a French count.

So he hired men who could compare Dickens’s lectures with Thackeray’s, or were familiar with the controversy over Mount Barghir, or who knew a murder mystery when they saw it. They wrote, and he read and sometimes edited, but usually approved, for he knew that newspaper success lay not so much in a choice of topics as in a choice of men. He knew that the success of an editorial page came less from inside opinions than from outside interest. Dana’s remarkable success in the exaltation of journalism to literary heights was won not so much through what he wrote, but through what he left other men free to write.

His own work as a writer for the Sun took but a fraction of his busy day. He dictated his articles to Tom Williams, his stenographer, a Fenian and a bold man.

“Can you write as fast as I talk?” asked Dana when Williams applied for the job.

“I doubt it, Mr. Dana,” said Williams; “but I can write as fast as any man ought to talk.”

For twenty years Tom Williams transcribed articles that absorbed the readers of the Sun, but his own heart was down the bay, near his Staten Island home, where he spent most of his spare time in fishing and sailing. It was always a grief to Williams to enter the office on an election or similarly important night, and to find that no one paid any attention to his stories about how the fish were biting.

Dana had no doubt—nor had any one, least of all those who came under his editorial condemnation—of his own ability as a trenchant writer. The expression of thought was an art which he had studied from boyhood. Whatever of the academic appeared in his early work had been driven out during his service on the Tribune and in the war, particularly the latter, for as a reporter for the government he learned to avoid all but the salients of expression. But as the editor of the Sun he found less delight in his own product than in the work of some other man whose literary ability answered his own standards of terseness, vigour, and illumination. The new man would help the Sun, and that was all that Dana asked.

That another man’s work should be mistaken for his own, or his own for another man’s, was to Dana nothing at all, except perhaps a source of amusement. The anonymity of the writers on the Sun was so complete that the public knew their work only as a whole; but whenever anything particularly biting or humorous appeared, the same public instantly decided that Dana must have written it.

No king, no clown, to rule this town!

That line, born in the Sun’s editorial page, will live as long as Shakespeare. In eight words it embodied the protest of New York against the arrogance and stupidity of machine political rule. Ten thousand times, at least, it has been credited to Dana, but as a matter of fact it was written by W. O. Bartlett.

Bartlett was one of those great newspaper writers whose fate—or choice—it is never to own a newspaper and never to attract public attention through the writing of signed articles or books. Writing was not primarily his profession, and by the older men of New York who remember him he is recalled as a brilliant lawyer rather than as a writer. He met Dana through Secretary Stanton, and he was the Sun’s attorney soon after Dana and his friends bought the paper. His law-offices were in the Sun Building, directly below Mr. Dana’s own offices. There, and also at the Hoffman House, where he lived when he was not on his estate at Brookhaven, Long Island, Mr. Bartlett wrote his articles for the Sun.

Bartlett was a writer of the school of simplicity. His style of reducing a proposition to its most elementary form, so that it was clear to even the Class B intellect, was the admiration and envy of all who knew his articles. It was an inspiration, too, to many young newspapermen of his day.

The manner of Mr. Arthur Brisbane of the Evening Journal, luring the reader into a sociological dissertation by first inquiring whether he knows “Why a Flea Jumps So Far,” is the Bartlett manner, with such modifications as are necessary to reach the attention of a group intellectually somewhat different from Bartlett’s readers. Only Bartlett did not spend too much time on the flea. Of the three men whose articles have most distinguished the first column of the Sun’s editorial page, each has had his own weapon when leading to attack. Dana struck with a sword. Mitchell used—and uses—the rapier. Bartlett swung the mace. It was jewelled with the gems of language, but still it was a mace; and if it crushed the skull of the enemy at the first blow, so much the better. It was Bartlett, for instance, who wrote the article in which the Democratic candidate for President in 1880, General Hancock, was referred to as “a good man, weighing two hundred and forty pounds.”

W. O. Bartlett wrote for the Sun from 1868 until his death in 1881. He was the foremost figure in the group of older men around Dana—the men who had been prominent in political and literary life before the Civil War. Other notable men of middle age who were chosen by Mr. Dana to write editorial articles were James S. Pike, Fitz-Henry Warren, Henry B. Stanton, and John Swinton.

James Shepherd Pike’s articles appeared more frequently in the columns of the Sun than Pike himself appeared in the office, for most of his work was done in Washington. He was about eight years older than Mr. Dana, but they were great friends from the earliest days of Dana’s Tribune experience. For five years, beginning in 1855, Pike was a Washington correspondent and one of the associate editors of the Tribune. During the Civil War he was United States minister to the Netherlands, a reward for his services in his home State, Maine, where he was useful in uniting the anti-slavery forces. He was a brother of Frederick A. Pike, a war-time Representative from Maine, whose “Tax, fight, emancipate!” was the Republican watchword from its utterance in 1861.

Pike was one of the group that supported Greeley for the Presidency in 1872. He was one of the really great publicists of his day. He wrote “The Restoration of the Currency,” “The Financial Crisis,” “Horace Greeley in 1872,” “A Prostrate State”—which was a description of the Reconstruction era in South Carolina—and “The First Blows of the Civil War,” this last a volume of reminiscent correspondence, some newspaper, some personal. The friendship and literary association of Pike and Dana lasted more than thirty years, and ended only with Pike’s death in 1882, just after he had passed threescore and ten.

Fitz-Henry Warren, who has been already referred to in this narrative as the author of the Tribune’s cry, “On to Richmond!” wrote many editorial articles for Dana, who had conceived a great admiration for Warren when both were in the service of the Tribune, Dana as managing editor and Warren as head of the Washington bureau. Warren emerged from the Civil War not only a major-general, but a powerful politician, and it was not until several years later, after he had served in the Iowa Senate and as minister to Guatemala, that Dana was able to bring the pen of this transplanted New Englander to the office of the Sun. Once there, it did splendid work.

It is not easy to identify the editorials that appeared in the Sun under the Dana régime; not so much because of the lapse of years, but because the spirit of Dana so permeated everything that was printed on his page that it is difficult to say with certainty, “This Dana wrote, this Bartlett, this Mitchell, this Warren, and this Pike.” But, for the purpose of giving some small idea of the grace and magnificence of Warren’s style, here is a paragraph from an editorial article known to have been written by him on the death of Charles Sumner in March, 1874:

Men spoke softly on the street; their very voices betokened the impending event, and even their footfalls are said to have been lighter than common. But in the neighborhood of the Senator’s house there was a sense of singular and touching interest. Splendid equipages rolled to the corner, over pavements conceived in fraud and laid in corruption, to testify the regard of their occupants for eminent purity of life. Liveried servants carried hopeless messages from the door of him who was simplicity itself, and to whom the pomp and pageantry of this evil day were but the evidences of guilty degeneracy. Through all those lingering hours of anguish the sad procession came and went.

On the sidewalk stood a numerous and grateful representation of the race to whom he had given the proudest efforts and the best energies of his existence. The black man bowed his head in unaffected grief, and the black woman sat hushing her babe upon the curbstone, in mute expectation of the last decisive intelligence from the chamber above.

General Warren continued to write for the Sun until 1876, and he died two years afterward, when he was only sixty-two years old, in Brimfield, Massachusetts, the town of his birth.

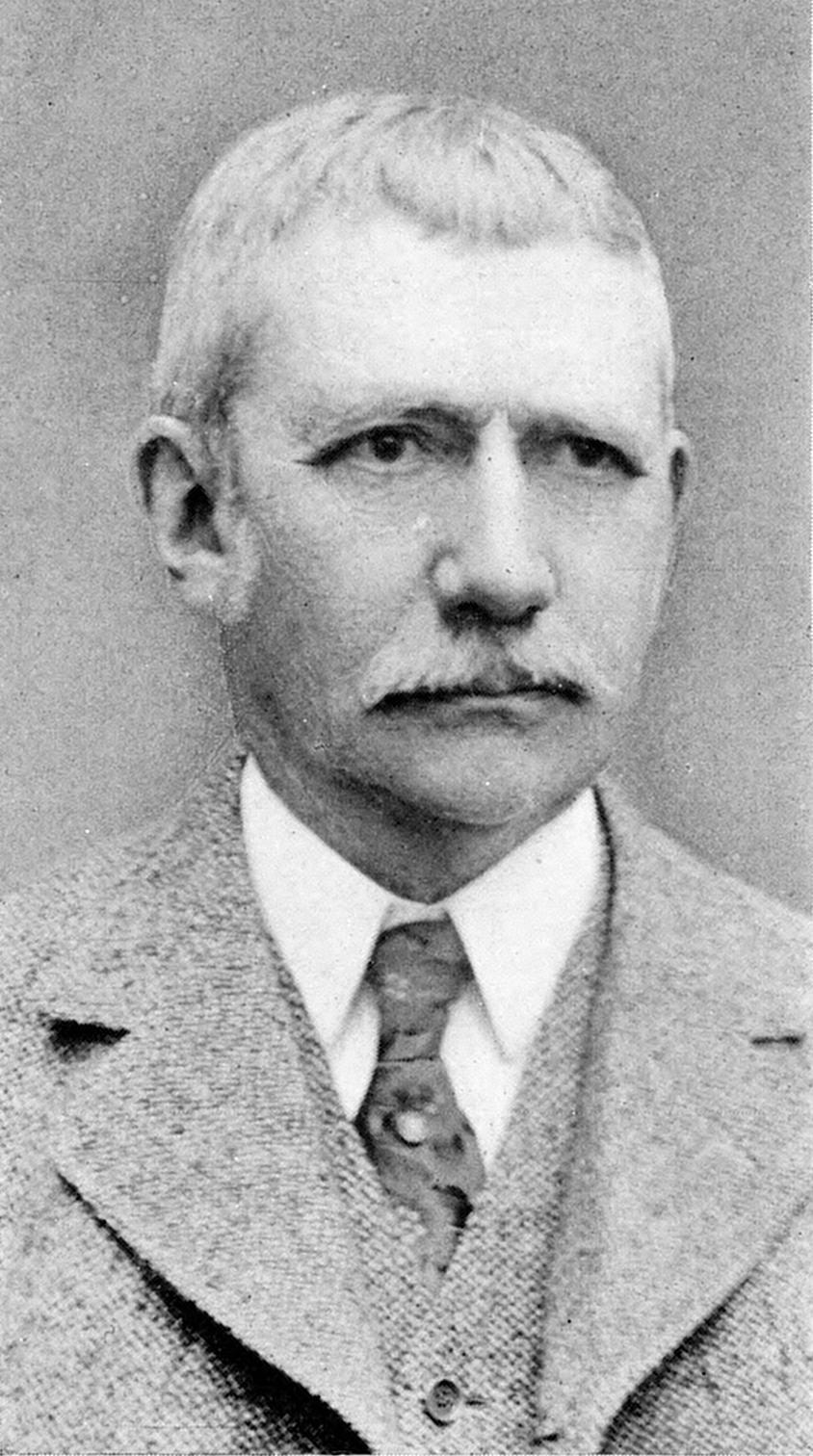

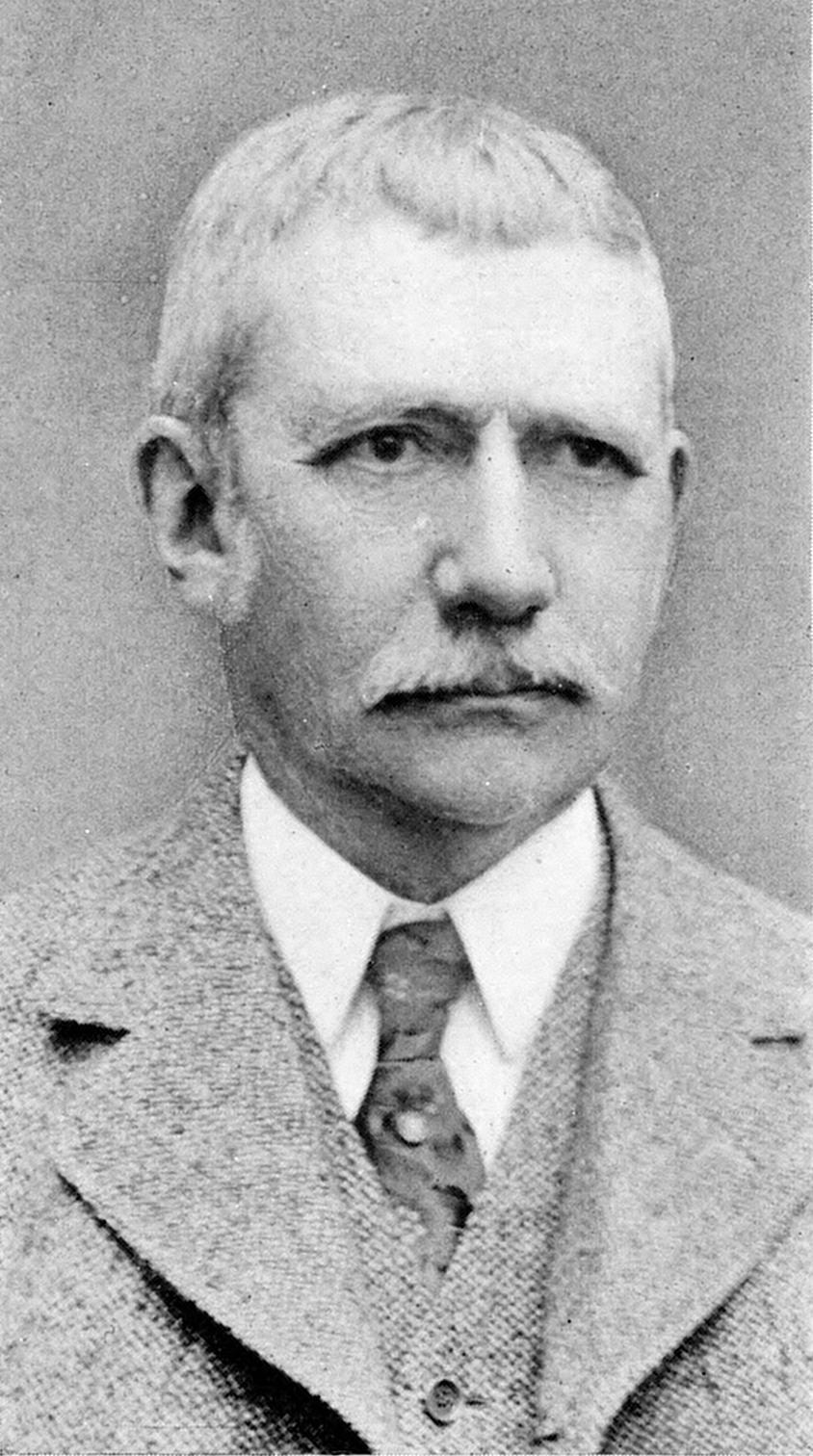

JOSEPH PULITZER

ELIHU ROOT

JUDGE WILLARD BARTLETT

Although Henry Brewster Stanton was a comparatively old man when he began writing for the Sun, his activities in that line lasted for nearly twenty years. In 1826, when he was twenty-one years old, he entered newspaper work on Thurlow Weed’s Monroe Telegraph, published in Rochester. Soon afterward he became an advocate of the anti-slavery cause. In 1840 he married Elizabeth Cady, and with her went abroad, where in Great Britain and France they worked for the relief of the slaves in the United States. It was during that journey that Elizabeth Cady Stanton signed the first call for a woman’s rights convention.

On his return to America Stanton studied law with his father-in-law, Daniel Cady. After his admission to the bar he practised in Boston, but he returned to New York and politics in 1847. He left the Democratic party to become one of the founders of the Republican party.

Dana met Stanton when the latter was a writer for the Tribune, and when Dana came into the control of the Sun he secured the veteran as a contributor. Stanton knew politics from A to Z, and his brief articles, filled with political wisdom and often salted with his dry humour, were just the class of matter that Dana wanted for the editorial page. Stanton was also a capable reviewer of books. He wrote for the Sun from 1868 until his death in 1887. Henry Ward Beecher said of him:

“I think Stanton has all the elements of old John Adams—able, staunch, patriotic, full of principle, and always unpopular. He lacks that sense of other people’s opinions which keeps a man from running against them.”

John Swinton was one of the few of Dana’s men who might be described as a “character.” He lived a double intellectual life, writing conservative articles in his newspaper hours and making socialistic speeches when he was off duty. Yet it was a double life without duplicity, for there was no concealment in it, no hypocrisy, and no harm. When he had finished his day in the office of the Sun, perhaps at writing some instructive paragraphs about the possibilities of American trade in Nicaragua, he would take off his skull-cap, place a black soft hat on his gray head, and go forth to dilate on the advantages of super-Fourierism to some sympathetic audience of socialists.

There was a story in the office that one evening Mr. Swinton, making a speech at a socialistic gathering, referred hotly to the editor of the Sun as one of the props of a false form of government, and added that “some day two old men will come rolling down the steps of the Sun office,” and that at the bottom of the steps he, Swinton, would be on top.

This may be of a piece with the story about Mr. Dana and the man with the revolver; but the young men in the reporters’ room liked to tell it to younger men. It probably had its basis in the fact that on the morning after a particularly ferocious assault on capital, John Swinton would poke his head into Mr. Dana’s room to tell him how he had given him the dickens the night before—information which tickled Mr. Dana immensely. And Dana never went to the bottom of the Sun stairs except on his own sturdy legs.

Swinton was a Scotsman, born in Haddingtonshire in 1830. He emigrated to Canada as a boy, learned the printer’s trade, and worked at the case in New York. After travels all over the country, he lived for a time in Charleston, South Carolina, and there acquired an abhorrence for slavery. He went to Kansas and took part in the Free Soil contest, but returned to New York in 1857 and began the study of medicine.

While so engaged he contributed articles to the New York Times, and Henry J. Raymond, who liked his work, took him as an editorial writer. He was the managing editor of the Times during the Civil War, and had sole charge during Raymond’s absences. At the end of the war Swinton’s health caused him to resign from the managing editorship, but he continued to write for the editorial page. He went to work on the Sun about 1877.

His specialty was paragraphs. Dana liked men who could do anything, but he also preferred that every man should have some specialty. Swinton had the imagination and the light touch of the skilful weaver of small items. Also, he was much interested in Central America, and his knowledge of that region was of frequent use to the Sun.

Swinton left the Sun in 1883 to give his whole time to John Swinton’s Paper, a weekly journal in which he expounded his labour-reform and other political views. He was the author of many pamphlets and several books, including a “Eulogy of Henry J. Raymond” and an “Oration on John Brown.”

Such were the editorial writers of what may be called the iron age of the Sun; the men who helped Dana to build the first story of a great house. As they passed on, younger men, some greater men, trained in the Dana school, took their places and spanned the Sun’s golden age—such men as E. P. Mitchell, Francis P. Church, and Mayo W. Hazeltine.

Meanwhile, on the other side of a partition on the third floor of the old brick building at the corner of Frankfort Street, another group of men were doing their best to advance Dana’s Sun by making it the best newspaper as well as the best editorial paper in America. These, too, were giants.