VIII

ON MOUNT WASHINGTON

Sunny Days and Clear Nights on the Highest Summit

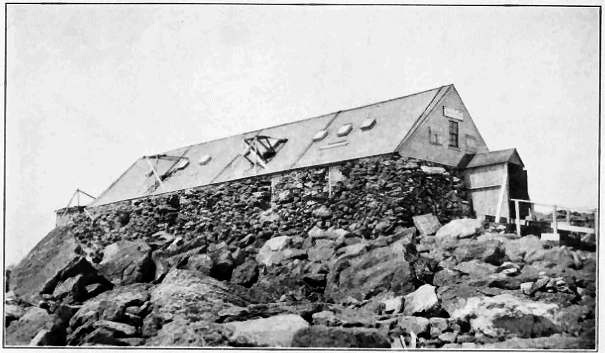

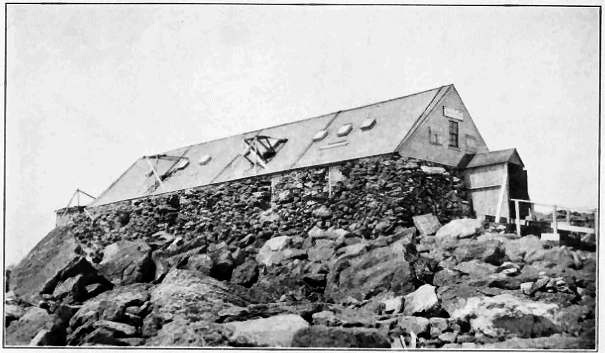

The dweller on the top of Mount Washington may have all kinds of weather in the twenty-four hours of a July day, or he may have a tremendous amount, all of one kind, extending through many days. It all depends on what winds Father Æolus keeps chained, perhaps in the deep caverns of the Great Gulf, or which ones he lets loose to rattle the chains of the Tip Top House. My four days there were such as the fates in kindly mood sometimes deal out to fortunate mortals. The land below was in a swoon of awful heat. People died like flies in cities not far to the southward. The summit had a temperature of June, and the wind that drifted in from Canada made the nights cool enough for blankets; all but one. The night before the Fourth we perspired, even in this wind of Hudson Bay, and the habitués of the hilltop were properly indignant. They had snowballed there for a brief hour on the July Fourth of the year before and these sudden changes were disquieting.

"It all depends on what winds Father Æolus keeps chained, perhaps in the deep caverns of the Great Gulf, or which ones he lets loose to rattle the chains of the Tip Top House"

Of these four gems of days the first was a pearl, two were amethystine, and the last was of lapis lazuli. The morning of the pearl broke after light rains in the valley below, the air so clear that the city of Portland lifted its spires on the eastern horizon just before sunrise and the blue water of Casco Bay flashed beyond it. Yet the nearer valleys were shrouded in the white mists that were mother-of-pearl, a matrix that gradually rose and blotted out the green and gray of granite hilltops below till the summit was a great ship, rock-laden, ploughing through a white tumultuous sea whose billows were fluffy clouds like those on which Jupiter of old sat and dispensed judgment on mankind. I know of nothing so much like this sea of white cloud surface seen from above as is the sea of Arctic ice under a summer sun, its white, sun-softened expanse crushed into flocculent pressure ridges of frozen tumult stretching as far as the eye can reach. Yet this is different in its strange beauty, for the Arctic ice changes its form only slowly, while this fleecy sea, seemingly so stable to the fleeting glance, changes shape before the next look can be given. No breath of wind may fan your brow on the summit, but the clouds below you tread a stately minuet, advancing, retreating, meeting and dividing, now a white Arctic sea, again a swiftly dignified dance by ghostly castles in Spain.

Often the near mists close in upon the summit and make all opaque, and the gray, shadowy hand of the cloud lies against your cheek and leaves a smear of cool moisture when it is withdrawn. On that morning when the summit and the day were bosomed together in a white pearl I saw the wayward moods of an imperceptible wind ordering this dance of the clouds. It passed down from the peak by the path that leads over the range to Crawford Notch, waving one line of mists eastward from the ridge until Boott's Spur and Tuckerman's Ravine stood clearly revealed, while on the west an obedient white wall stood, wavering indeed, but holding its ground from the margin of the path high into the sky toward the zenith. For nearly half an hour any alpinist climbing over the head wall of Tuckerman's in sunshine would have seen his way clearly to this Crawford path, and, going westward, have stepped into the white mystery of the mists on the farther verge.

Again the imperceptible winds beckoned and the clouds whirled up from Pinkham Notch and blotted out the spur and the ravine, pirouetting up to meet their partners while the latter retreated, fluttering lace skirts behind, the high-walled chasm of clear space between them passing over the ridge and swinging north until met by an eruption of white dancers out of the Great Gulf and across the railroad track. Then all whirled together up the rough rock tangle of the central cone and blotted out the world in a pearly opacity.

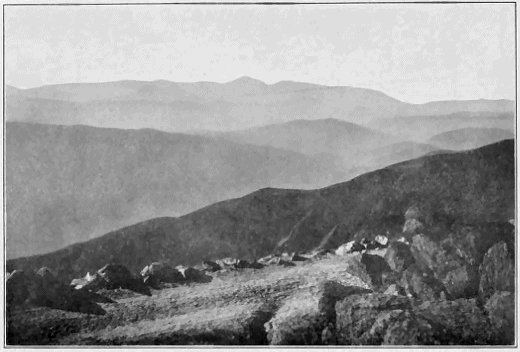

The clouds that morning were born in the lowlands and ascended to the summit from all sides, out of Huntington and Tuckerman Ravines, out of Oakes Gulf and Great Gulf and up from Fabyan's by way of the Base Station and the Mount Washington Railroad, enfolding the summit only after they had shown the marvels of their upper levels all about the foundations of the central cone. Then, after the white opalescence of the conquest of the peak the whirling dervishes above, for an hour or two, now occluded, again revealed, what was below. For half an hour they danced along the northern peaks, now hiding, now disclosing portions of them, but always during that time showing the peak of Adams, a clearly defined purple-black pyramid, framed in their fleece. After that for a long time they lifted bodily for ten-minute spaces, revealing another body of mists below, their upper surface far enough down so that the castellated ridge of Boott's Spur, Mount Monroe, Mount Clay and Nelson Crag stood out above them.

Here were clouds above clouds, the upper levels whirling in wild dances, fluttering together and again parting to let the sun in on the summit and on the levels below whence rose fleecy cloud rocks of white, tinged often with the rose of sunlight, mountain ranges of semi-opaque mists that changed without seeming to move and showed oftentimes a curious semblance in white vapor to the land formation as it is revealed below on a clear day. Out of these lower clouds came sometimes sudden jets of vapor, as if the winds below found fumaroles whence they sent quick geysers of mists, vanishing fountains of a magic garden of the gods. Old Merlin, long banished from Arthur's Court in the high Welsh hills, may well have found a retreat in this new world Cærleon, nor did ever knight of the Round Table see more potent display of his powers of illusion and evasion than were here shown for any man who had climbed the high peak on that day of pearl cloud magic.

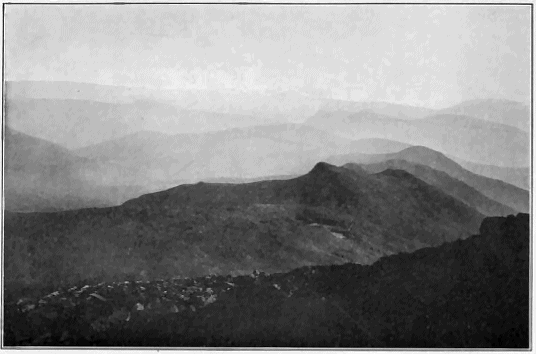

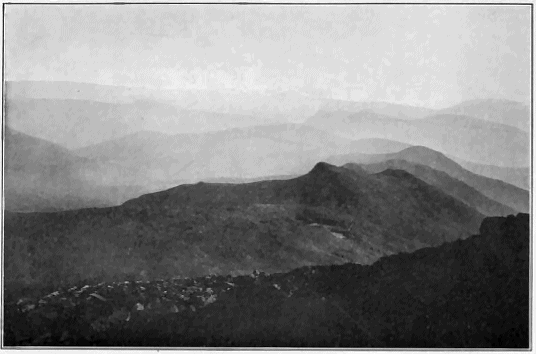

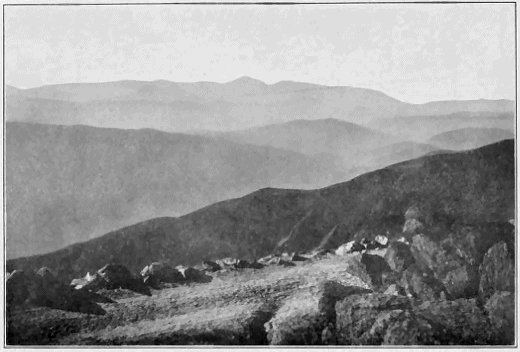

Afterward came two days of fervent sun on clear peaks that stand all about the horizon from Washington summit, half islanded in an amethystine heat haze, as beautiful, seen from the wind-swept pinnacle, as if old Merlin after a day of tricks with pearls had ground all the gems of his magic storehouse to blue dust that filled the valleys of all the mountain world. On those days few men climbed the peak, but all the butterflies of the meadows and valleys far below danced up and held revels in the scent of the alpine plants, then in the full joy of their July blooming. The more distant valleys were deeply hazed in this amethystine blue, but the nearer peaks and plateaus stood so clear above them that it seemed as if one might leap to the lakes of the clouds or step across the great gulf to Jefferson in one giant's stride. I have heard a man on the rim of the Grand Cañon in Arizona declaring that he could throw a stone across its thirteen miles. So on those days in the high air miles seemed but yards, and only in the actual test of travel did one realize how far the feet fall behind the eye in the passage of distances.

"The more distant valleys were deeply hazed in this amethystine blue, but the nearer peaks and plateaus stood so clear above them that it seemed as if one might leap to the Lakes of the Clouds or step across the Great Gulf to Jefferson in one Giant's stride."

At nightfall one realized how that heat haze not only possessed the valleys but the air high above them, for the sun, descending, grew red and dim and finally was swallowed up in the mists of his own creating long before he had reached the actual horizon's rim. Under his passing one lake after another to westward flashed his mirrored light back in a dazzling gleam of silver, then faded again to become a part of the blue dust of the distance. By their flashes they could be counted, and it was as if each signalled good night to the summit as the day went on. Eastward the purple shadow of the apex moved out across the Alpine garden, joined that of the head wall of Huntington Ravine, and, flanked by those of the Lion's Head and Nelson Crag, went on toward the horizon. Clearly defined on the light-blue haze where the sun's rays still touched, this deep pyramid of color moved majestically out of the Notch and up the slope of Wildcat Mountain, leapt Carter Notch and from the high dome of the farther summit put the Wild River valley in shadow as it went on, up Baldface and on again across the nearer Maine ranges, till it set its blunt point on the heat-haze clouds along the far eastern horizon. Nothing could be more expressive of the majesty of the mountain than to thus see its great shadow move over scores of miles of earth and on and up into the very heavens.

It was as if God withdrew the mountain for the night into the sky, leaving the watcher on that great ledge-laden ship which is the very summit, plunging on over dark billows with the winds of space singing wild songs in the rigging. Beneath is the blue-black sea of tumultuous mountain waves that ride out from beneath the prow and on into the weltering spindrift haze of distance where sea and sky are one. In the full night the winds increase and find a harp-string or a throat in every projection of the pinnacle ledges whence to voice their lone chanteys of illimitable space. It is the same world-old song that finds responsive echoes in man's very being but for which he can never find words, the chantey of the night winds that every sailor has heard from the fore-top as the ship plunges on in the darkness when only the dim stars mark the compass points and the very ship itself is merged far below in the murk of chaos returned. What the night may be during a storm on this main-top of the great mountain ship only those who have there endured it may tell; my nights there were like the days, fairy gifts out of a Pandora's box that often holds far other things beneath its lid.

"Dawn on the mornings of those days was born out of the sky above the summit, as if the fading stars left some of their shine behind them"

Dawn on the mornings of those days was born out of the sky about the summit as if the fading stars left some of their shine behind them, a soft, unworldly light that touched the pinnacles first and anon lighted the mountain waves that slid out from under the prow of the ship and rode on into the flushing east. As the heat haze at night had absorbed the red sun in the west, so now it let it gently grow into being again from the east. In its crescent light he who watched to westward could see the mountain come down again out of the sky into which it had been withdrawn. Out of a broad, indistinct shadow that overlaid the world it grew an outline that descended and increased in definiteness till the apex was in a moment plainly marked on the massed vapors that obscured the horizon line. Down these it marched grandly, touching indistinct ranges far to westward, more clearly defined on the Cherry Mountains and the southerly ridges of the Dartmouth range, and becoming the very mountain itself as its point touched the valley whence flows Jefferson Brook and the slender thread of the railway climbs daringly toward the summit.

Below in a thousand sheltered valleys the hermit thrushes sang greetings to the day. Far up a thousand slopes the white-throated sparrows joined with their thin, sweet whistle, and higher yet the juncos warbled cheerily, but no voice of bird reaches the high summit. The only song there is that of the wind chanting still the thrumming runes of ancient times, sung first when rocks emerged out of chaos and touched with rough fingers the harp strings of the air. To such music the light of day descends from above, and the shadows of night withdraw and hide in the caves and under the black growth in the bottoms of ravines and gulfs. Rarely does one notice this music in the full day. Then the rough cone even is a part of man's world, built on a sure foundation of the familiar, friendly earth. It is only the darkness of night that whirls it off into the void of space and sets the eerie runes in vibration. Few nights of the year are so calm there that you do not hear them, and even in their gentlest moods they come from the voices of winds lost in the void, little winds, perhaps, rushing shiveringly along to find their way home and whistling sorrowfully to themselves to keep their courage up.

Man comes to the summit at all hours and by many paths. Often in that darkest time which precedes the dawn one may see firefly lights approaching from the northeast, bobbing along in curious zigzags. These will-o'-the-wisps are pedestrians, climbing by the carriage road to greet the first dawn on the summit and watch the sun rise, carrying lanterns meanwhile lest they lose the broad, well-kept road and fall from the Cape Horn bend into the solemn black silence of the Great Gulf. The voices of these are an alarm clock to such as sleep on the summit, calling them out betimes to view the wonders they seek. By day men and women appear on foot from the most unexpected places. The Crawford and Gulf Side trails, Tuckerman's and the carriage road bring them up by accepted paths, but you may see them also clambering over the head wall of Huntington's or the Gulf, precipitous spots that the novice would think unsurmountable.

These are the "trampers," as the habitués of the mountain summit call them. But the carriage road brings many who ride luxuriously up for four hours behind two, four or six horses, or flash up in less than an hour to the honk of automobile horns and the steady chug of gasolene engines. The old-time picturesque burros that patiently bore their riders up the nine miles of the Crawford trail have gone, probably never to return, and the horseback parties once so common are now rare. But by far the greater numbers climb the mountain by steam. From the northerly slope of Monroe, over beyond the Lakes of the Clouds, I watched the trains come, clanking caterpillars that inch-worm along the trestles of the cogged railroad, clinking like beetles and sputtering smoke and steam as only goblin caterpillars might, finally becoming motionless chrysalids on the very summit. From these burst forth butterfly crowds that put to shame with their raiment the gauzy-winged beauties that flutter up the ravines to enjoy the sweets of the Alpine Garden. Then for a brief two hours on any bright day the bleak summit becomes a picnic ground, bright with gay crowds that flutter from one rock pinnacle to another and swirl into the ancient Tip Top house to buy souvenirs and dinner, restless as are any lepidoptera and as little mindful of the sanctity of this highest altar of the Appalachian gods. Soon these have reassembled once more in their chrysalids that presently retrovert to the caterpillar stage and crawl clanking and hissing down the mountain, inching along the trestles and vanishing anon into the very granite whence you hear them clanking and sputtering on. Amid all the weird play of nature in lonely places the summit has no stranger spectacle than this.

The day of lapis lazuli began with a break in the intense heat, a day on which cumulus clouds rolled up thousands of feet above the summit in the thin air and cast their shadows before them, to race across the soft amethyst of the miles below and deepen it with their rich blue out of which golden sun-glints flashed still, racing shifting breaks in the cloud masses above. The wind increased in velocity toward mid-afternoon and cumulus massed in nimbus on the far horizon to the northwest out of which the flick of red swords of lightning and the battle roar of thunder sounded nearer and nearer. Mightily the black majesty of the storm moved up to us, wiping out earth and sky in its progress, the rolling edges of its topmost clouds still golden with the color of the sun that sank behind them. Here was a glory such as day nor night, sunrise nor sunset, had been able to show me.

The pagan gods of the days long gone seemed to come forth out of the summits far to the northwest and do battle, but half-concealed by their clouds. Swords flashed high and javelins flew and the clash of shields and the rumble of chariot wheels came to the ear in ever increasing volume as the tide of battle swept on and over the summit. A moment and we should see the very cohorts of Mars himself in all their shining fury, but father Æolus let loose all the winds at once from his caverns, Jupiter Pluvius opened wide the conduits of the clouds and the world, even the very summit thereof, was drowned in the gray tumult of the rain.