Chapter 8. Random Vectors and joint Distributions

8.1. Random Vectors and Joint Distributions*

A single, real-valued random variable is a function

(mapping) from the basic space Ω to the real line. That is, to each possible outcome ω

of an experiment there corresponds a real value t=X(ω). The mapping induces a

probability mass distribution on the real line, which provides a means of making probability

calculations. The distribution is described by a distribution function FX. In the

absolutely continuous case, with no point mass concentrations, the distribution may also be

described by a probability density function fX. The probability density is the

linear density of the probability mass along the real line (i.e., mass per unit length).

The density is thus the derivative of the distribution function. For a

simple random variable, the probability distribution consists of a point mass pi at

each possible value ti of the random variable. Various m-procedures and m-functions aid

calculations for simple distributions. In the absolutely continuous case, a simple approximation

may be set up, so that calculations for the random variable are approximated by calculations on

this simple distribution.

Often we have more than one random variable. Each can be considered separately, but

usually they have some probabilistic ties which must be taken into account when they

are considered jointly. We treat the joint case by considering the individual random

variables as coordinates of a random vector. We extend the techniques for a single

random variable to the multidimensional case. To simplify exposition and to keep calculations

manageable, we consider a pair of random variables as coordinates of a two-dimensional

random vector. The concepts and results extend directly to any finite number of random

variables considered jointly.

Random variables considered jointly; random vectors

As a starting point, consider a simple example in which the probabilistic interaction between

two random quantities is evident.

Example 8.1. A selection problem

Two campus jobs are open. Two juniors and three seniors apply. They seem equally

qualified, so it is decided to select them by chance. Each combination of two is

equally likely. Let X be the number of juniors selected (possible values 0, 1, 2) and

Y be the number of seniors selected (possible values 0, 1, 2). However there are only

three possible pairs of values for  , or

, or  . Others

have zero probability, since they are impossible. Determine the probability for each of the

possible pairs.

. Others

have zero probability, since they are impossible. Determine the probability for each of the

possible pairs.

SOLUTION

There are  equally likely pairs. Only one pair can be both juniors. Six

pairs can be one of each. There are

equally likely pairs. Only one pair can be both juniors. Six

pairs can be one of each. There are  ways to select pairs of seniors. Thus

ways to select pairs of seniors. Thus

These probabilities add to one, as they must, since this exhausts the mutually exclusive

possibilities. The probability of any other combination must be zero. We also have the

distributions for the random variables conisidered individually.

We thus have a joint distribution and two individual or marginal distributions.

We formalize as follows:

A pair  of random variables considered jointly is treated as the pair

of coordinate functions for a two-dimensional random vector

of random variables considered jointly is treated as the pair

of coordinate functions for a two-dimensional random vector  . To each ω∈Ω, W assigns the pair of real numbers

. To each ω∈Ω, W assigns the pair of real numbers  , where

X(ω)=t and Y(ω)=u. If we represent the pair of values

, where

X(ω)=t and Y(ω)=u. If we represent the pair of values  as the point

as the point

on the plane, then

on the plane, then  , so that

, so that

is a mapping from the basic space Ω to the plane R2. Since W is a function,

all mapping ideas extend. The inverse mapping W–1 plays a role

analogous to that of the inverse mapping X–1 for a real random variable. A two-dimensional

vector W is a random vector iff W–1(Q) is an event for each reasonable set

(technically, each Borel set) on the plane.

A fundamental result from measure theory ensures

is a random vector iff each of the coordinate functions X and Y is a random variable.

is a random vector iff each of the coordinate functions X and Y is a random variable.

In the selection example above, we model  (the number of juniors selected) and

Y (the number of seniors selected) as random variables. Hence the vector-valued

function

(the number of juniors selected) and

Y (the number of seniors selected) as random variables. Hence the vector-valued

function

Induced distribution and the joint distribution function

In a manner parallel to that for the single-variable case, we obtain a mapping of

probability mass from the basic space to the plane. Since W–1(Q) is an event

for each reasonable set Q on the plane, we may assign to Q the probability mass

Because of the preservation of set operations by inverse mappings as in the single-variable case,

the mass assignment determines

PXY as a probability measure on the subsets of the plane R2. The argument

parallels that for the single-variable case. The result is the probability distribution

induced by  . To determine the probability that the

vector-valued function

. To determine the probability that the

vector-valued function  takes on a (vector) value in region Q, we simply

determine how much induced probability mass is in that region.

takes on a (vector) value in region Q, we simply

determine how much induced probability mass is in that region.

Example 8.2. Induced distribution and probability calculations

To determine  , we determine the region for which the

first coordinate value (which we call t) is between one and three and the second

coordinate value (which we call u) is greater than zero. This corresponds to

the set Q of points on the plane with 1≤t≤3 and u>0. Gometrically,

this is the strip on the plane bounded by (but not including) the horizontal axis and by the

vertical lines t=1 and t=3 (included). The problem is to determine how much

probability mass lies in that strip. How this is acheived depends upon the nature of the

distribution and how it is described.

, we determine the region for which the

first coordinate value (which we call t) is between one and three and the second

coordinate value (which we call u) is greater than zero. This corresponds to

the set Q of points on the plane with 1≤t≤3 and u>0. Gometrically,

this is the strip on the plane bounded by (but not including) the horizontal axis and by the

vertical lines t=1 and t=3 (included). The problem is to determine how much

probability mass lies in that strip. How this is acheived depends upon the nature of the

distribution and how it is described.

As in the single-variable case, we have a distribution function.

Definition

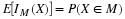

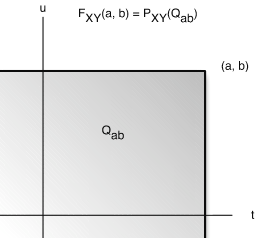

The joint distribution function FXY for  is

given by

is

given by

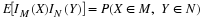

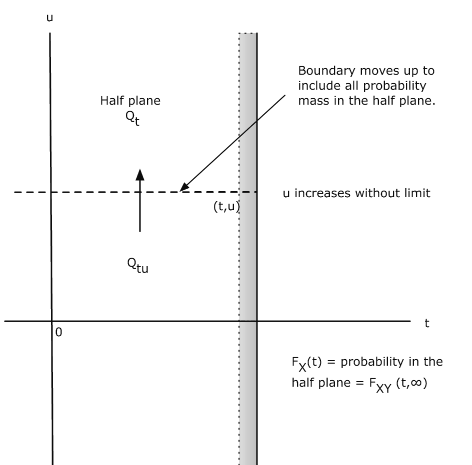

This means that  is equal to the probability mass in the region Qtu

on the plane such that the first coordinate is less than or equal to t and the second

coordinate is less than or equal to u. Formally, we may write

is equal to the probability mass in the region Qtu

on the plane such that the first coordinate is less than or equal to t and the second

coordinate is less than or equal to u. Formally, we may write

Now for a given point (a,b), the region Qab is the set of points (t,u) on

the plane which are on or to the left of the vertical line through (t,0)and

on or below the horizontal line through (0,u) (see Figure 1 for specific point t=a,u=b).

We refer to such regions as semiinfinite intervals on the plane.

The theoretical result quoted in the real variable case extends to ensure that a distribution on the

plane is determined uniquely by consistent assignments to the semiinfinite intervals

Qtu. Thus, the induced distribution is determined completely by the joint

distribution function.

Distribution function for a discrete random vector

The induced distribution consists of point masses. At point  in the range of

in the range of

there is probability mass

there is probability mass  . As in the general case, to determine

. As in the general case, to determine  we determine how much probability

mass is in the region. In the discrete case (or in any case where there are point mass

concentrations) one must be careful to note whether or not the boundaries are

included in the region, should there be mass concentrations on the boundary.

we determine how much probability

mass is in the region. In the discrete case (or in any case where there are point mass

concentrations) one must be careful to note whether or not the boundaries are

included in the region, should there be mass concentrations on the boundary.

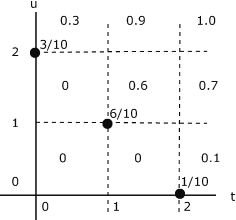

Example 8.3. Distribution function for the selection problem in Example 8.1 The probability distribution is quite simple. Mass 3/10 at (0,2), 6/10 at (1,1), and

1/10 at (2,0). This distribution is plotted in Figure 8.2. To determine (and visualize)

the joint distribution function, think of moving the point  on the plane. The

region Qtu is a giant “sheet” with corner at

on the plane. The

region Qtu is a giant “sheet” with corner at  . The value of

. The value of  is the amount of probability covered by the sheet. This value is constant over any grid

cell, including the left-hand and lower boundariies, and is the value taken on at the lower

left-hand corner of the cell. Thus, if

is the amount of probability covered by the sheet. This value is constant over any grid

cell, including the left-hand and lower boundariies, and is the value taken on at the lower

left-hand corner of the cell. Thus, if  is in any of the

three squares on the lower left hand part of the diagram, no probability mass is covered

by the sheet with corner in the cell. If

is in any of the

three squares on the lower left hand part of the diagram, no probability mass is covered

by the sheet with corner in the cell. If  is on or in the square having probability

6/10 at the lower left-hand corner, then the sheet covers that probability, and the value of

is on or in the square having probability

6/10 at the lower left-hand corner, then the sheet covers that probability, and the value of

. The situation in the other cells may be checked out by this procedure.

. The situation in the other cells may be checked out by this procedure.

Distribution function for a mixed distribution

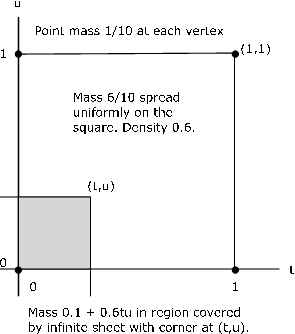

Example 8.4. A mixed distribution

The pair  produces a mixed distribution as follows (see Figure 8.3)

produces a mixed distribution as follows (see Figure 8.3)

Point masses 1/10 at points (0,0), (1,0), (1,1), (0,1)

Mass 6/10 spread uniformly over the unit square with these vertices

The joint distribution function is zero in the second, third, and fourth quadrants.

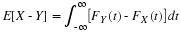

If the joint distribution for a random vector is known, then the distribution for each of the

component random variables may be determined. These are known as marginal distributions. In general, the converse is not true. However, if the component random variables form an

independent pair, the treatment in that case shows that the marginals determine the joint

distribution.

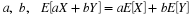

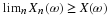

To begin the investigation, note that

Thus

This may be interpreted with the aid of Figure 8.4. Consider the sheet for point  .

.

If we push the point up vertically, the upper boundary of Qtu is pushed up until eventually

all probability mass on or to the left of the vertical line through  is included. This

is the total probability that X≤t. Now FX(t) describes probability mass on the line.

The probability mass described by FX(t) is the same as the total joint probability mass on

or to the left of the vertical line through

is included. This

is the total probability that X≤t. Now FX(t) describes probability mass on the line.

The probability mass described by FX(t) is the same as the total joint probability mass on

or to the left of the vertical line through  . We may think of the mass in the half

plane being projected onto the horizontal line to give the marginal distribution for X.

A parallel argument holds for the marginal for Y<

. We may think of the mass in the half

plane being projected onto the horizontal line to give the marginal distribution for X.

A parallel argument holds for the marginal for Y<