CHAPTER IX

FIVE STAGES

The “Potential” in Political Geography Examples: The Primitive Trackways: The Roman Road System: The Earlier Mediaeval Period: The Later Mediaeval Period: The Turnpike Era.

i

Let us next turn to a very rough sketch of the development of the history of the English Road: the stages through which its development has passed, measured, not from cause to effect, but in time.

Before turning to this I would first define the use of a certain word already used which will recur and may be unfamiliar to some of my readers. It is a word taken as a metaphor from physical science, and one of the utmost value in political geography. It is the word “potential.”

We talk of the “potential” between two commercial centres, or between a capital and a port, or between a mineral producing region and an agricultural region, or between a region whence barbarians desire to invade fertile civilized land and the centre of the fertile civilized land which desires to defend itself, etc., etc., and our use of this word “potential” is drawn from the doctrine of physical science that energy in open shape, energy at work, is given its opportunity by the tendency of two points to establish a communication: the tendency of two separate situations to establish unity, the tendency of a hitherto “potential”—that is, only “possible,” not yet “actual”—force to realize itself. For instance, you will have a highly charged electrical area tending to discharge itself by the line of best conduction. You will have a head of water creating a “potential”: a reservoir a hundred feet above the valley has to be connected with the floor of the valley by a tube to turn the potential energy into actual energy and to drive a turbine.

Now, in the development of the road system we metaphorically use this word “potential” in just the same fashion. For instance: there was originally no bridge across a river because the people in the town on one side of it had no particular reason to cross to barren land upon the other. The town gradually developed into a holiday resort. The only place for a good golf links was on the far side of the river, and visitors who lived in the town during their holidays wanted to go during part of the day to the golf links. A “potential” was established. Thus there has always been a most powerful “potential” between London and Dover, between the great commercial centre of the island and the port nearest to the Continent. That is a “potential” which has worked throughout the whole of English history. We can watch other potentials at work in different periods arising and dying out again. For instance, during the Norman and early Angevin period there was a very strong “potential” between the middle north coast of France and the coast of Sussex, with a corresponding development of traffic. The principal people in England were also great land owners and officials on the coast immediately opposite. That “potential” died down until the revival of modern steam traffic. Again, there is a “potential” to-day between any coal field and any centre of consumption of wealth distant from that coal field. So there is between any coal field and any great port. Again, you will have a strategic “potential.” A particular point of no economic value may be of the utmost strategic value. The holding of it may make all the difference to the defenders of the frontiers, and in that case a “potential” exists which is the driving motive for a road between the capital and the point in question.

With this note in mind we can proceed to some sketch of the history of the English Road.

ii

The development of the English Road up to the present turning-point in its history, following, as we have seen, the political story of the island, falls into five divisions.

A.—First came the primitive trackways, the chief of which must have been artificially strengthened, and some of which may have been, in sections at least, true roads up to the Roman invasions.

B.—Next came the Roman road system, which was presumably developed in the second century of our era. This is the framework of all that followed. All our roads from that date (eighteen hundred years ago) to modern times have sprung from and have grown in connection with this original set plan or framework. That is true, no doubt, of all western countries, but it is especially true of England. The English road system is the product in every age of the great Roman scheme, the relics of which are more marked in England than they are anywhere else in the world.

This point is the master point of the whole story. It is a point upon which popular history has completely lost its way. Popular history represents the Roman occupation of this island as an accident, a sort of interlude between the native British period and a later and separate “English” period which arose upon the invasion of the country by German tribes from beyond the North Sea. That is not the history of England at all. The history of England is the history of a Roman province.

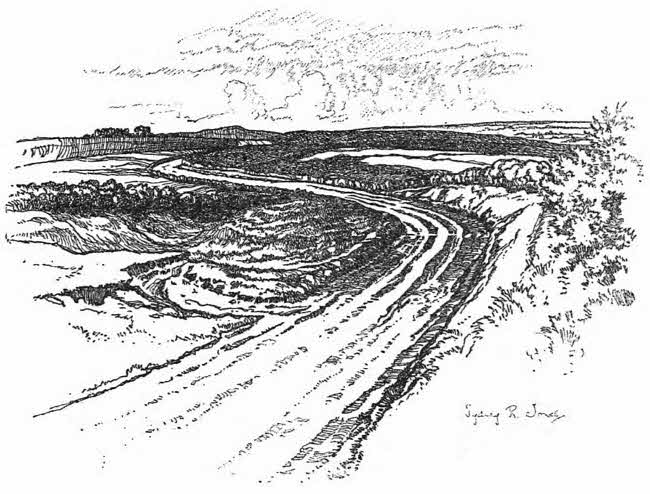

THE EARLIEST ROAD

England began by being, like everything else in the North and West, barbaric. It was civilized from the Mediterranean and made a part of the Roman Empire—that is, of one common civilization—one great state stretching from the Grampians to the Euphrates, and from the Sahara to the North Sea. This civilizing imprint of the Roman Empire Britain has never lost.

Our civilization fell into decay, as did that of the whole of the rest of Europe. The decay was not due to the pirate raids from North Germany and Holland any more than it was due to the raids of the Scottish Highlanders, which were just as frequent and violent, or the raids of Irish pirates from the west, which were at one moment so severe as to put up a separate realm on the west coast of this island. The history of England is continuous, and its foundation, from which we get all our institutions, more than half our language, all our ideas and religion and the rest of it, is in the 400 years of high civilization between the landing of the Roman armies and the breakdown of the imperial system in the West.

The Roman Road is the true and only root of the road system of Britain. All our local roads can be found developing slowly from the Roman roads of the district which had preceded them, and it is nearly always possible to trace the causes which led to each particular local system. In each you find the Roman Road is the backbone of the affair, and the later local roads existing only as developments of and changes from this basic Roman plan.

C.—The third division is one for which we have little direct, but plenty of indirect, evidence, and the remains of which are with us upon every side. It is the growth in the Early Middle Ages, presumably from about the Angevin period, of the mediaeval road system which was the deflection and extension of the old Roman road system. At the end of the Empire, during the Dark Ages (i.e. from the fifth to the eleventh century), though the Roman road system had remained the only available one, it had decayed, and numerous modifications of it had already appeared; but with the Early Middle Ages those modifications seem to have grown prodigiously, and the indirect network of local roads would then seem to have arisen.

D.—The fourth chapter is even more obscure. It is a partial decline, only affecting certain districts, and affecting some much more than others: a decline which corresponds more or less to the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century. It went with the flooding of the fen lands, with the breakdown of central authority, the increase of local interests, and so on.

E.—The fifth chapter is the great revolution in road planning and construction which may be called the turnpike era: beginning early in the eighteenth century and flourishing at its close.

The turnpike system continued to develop with continual changes through three or four generations. It survived the competition of the railroads. It was vastly improved by the new local legislation of from forty to twenty years ago. It left us with the road system we now enjoy, which must, under the pressure of quite recent changes, be modified if our communications are to be saved, or, at any rate, to keep pace with the present conditions of travel.