CHAPTER X

THE TRACKWAYS

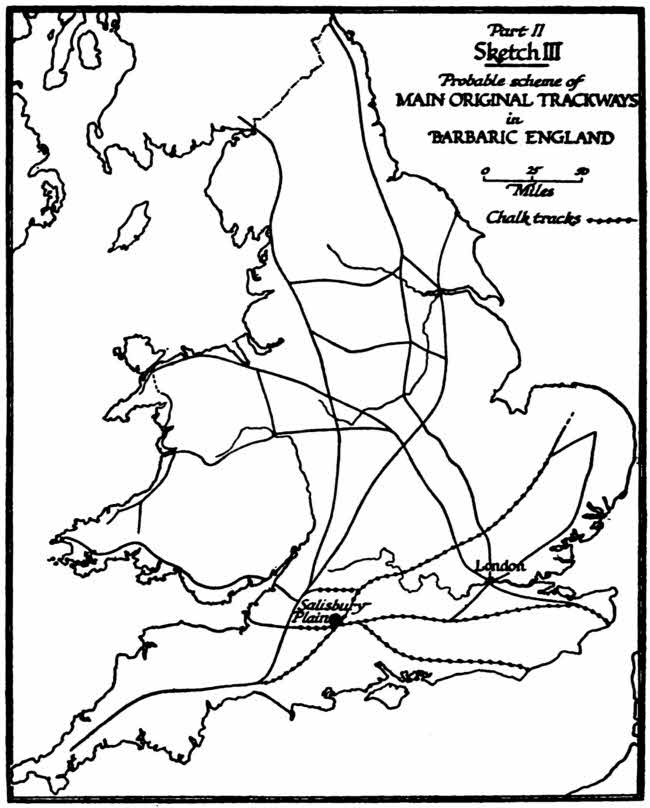

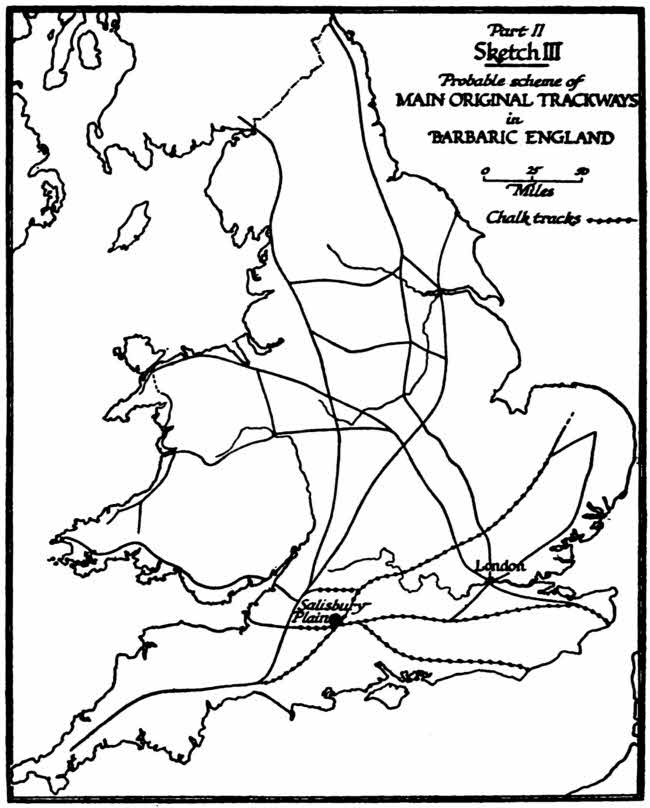

The Three Divisions of the British Pre-Roman Road System—The System of which Salisbury Plain was the “Hub”: The System Connected with London: Cross-Country Communications—The Three Factors which Have Determined Travel in Britain.

i

The origin of the trackways is, of course, unknown, and can only be guessed at by inference; but their character, and especially the geographical causes which determined their trace, we can establish on the largest lines with some accuracy.

We must not lose ourselves in that kind of speculation which has been so dear to the academies, and which is usually very futile. As to the order in which the development took place we have no evidence whatever: for instance, as to the date of the founding of London, or of its size before the Roman occupation; nor have we similar evidence with regard to any of the centres of England for the uniting of which roads would arise. But we have relics of the trackways before us. We have the geographical conditions almost unchanged, and we have the indication of Roman roads clearly based upon particular existing trackways, and therefore suggesting what the scheme was before the Roman engineers set to work.

Roughly speaking, the British pre-Roman road system fell into three divisions.

There was, first of all, a division (possibly the earliest to develop of all) which had for its “hub” Salisbury Plain, and from that centre a whorl, rather than a wheel, of diverging approaches to the coast.

There was, secondly, the system turning upon the crossing of the Thames at London as a “hub.” It is this second system which was so largely developed in the historical period and which still governs our main roads and railways to-day.

Thirdly, there was the series of cross-communications, of which the most important by far was the track leaving the Exe and making for the Humber.

The British trackways formed along these three systems discovered and used the best passages of the rivers, some of which the Romans changed, to which they added a certain number, but which, in the main, they retained. They also indicate, though less certainly, the town centres which have remained through the centuries the same, and they were also determined by the main centres of agricultural population and, to a much less extent, by the presence of mines.

Part II, Sketch III, Probable scheme of MAIN ORIGINAL TRACKWAYS in BARBARIC ENGLAND

The system of which Salisbury Plain appears to have been the “hub” we presume to be the earliest because it was dependent almost entirely upon surface: good going over dry land. It is to be presumed that the earliest system would be that prevalent when men were less able to give artificial aid to the Road, to harden it, to construct causeways or approaches; when they were less able to drain marshes; when they had not yet cleared forests. Now, of all the soils which make up the surface of Britain chalk is the best surface for this purpose. It has two characters which give it this character. In the first place, it is self-drained and always passable even in our wettest seasons; and, in the second place, it does not carry tangled undergrowth, and even its woods (which are not as a rule continuous) are commonly of beech—the easiest of all woods to pass through in travel, from the absence of scrub beneath the branches.

It so happens that the chalk is, in this country, distributed in great continuous lines and compact areas which lend themselves admirably to the development of an earlier track system. You can follow chalk with little interruption from the open central space, Salisbury Plain, south-eastward to the Channel, to the Dorset coast (“Dorset” from the country of the “Durotriges,” a British tribe whose name survives in that of the modern county[1]), and the first in order of the tracks led there. The chalk could equally be followed to the neighbourhood of Southampton Water. A third line led along the confused Hampshire chalk to the definite ridge of the Sussex Downs, and so to the harbours of the Sussex coast and of Kent.

The fourth, with some interruption, led along the north downs to Canterbury, whence tracks would radiate to the ports of Kent.

A fifth followed the Berkshire Downs and the Chilterns, and so led on to the Wash and earlier parts of the Norfolk coast, which have now apparently disappeared in erosion.

The sixth line led with more difficulty (and has been more obliterated by later Roman work) directly westward to the mines of the Mendips, and to the borders of the Severn estuary. It could not take advantage of the chalk beyond Wiltshire, but it had fairly dry going along the ridge of the Mendips.

The seventh, it must be presumed, though the traces are largely lost, used the height of the Cotswolds; but here the soil, being oolitic and not chalk, was much less favourable and the extension northward ceased earlier.

This system, then, we regard as the earliest of all.

ii

The second system, as I have said, seems to have been connected with London, but here the later track of the Roman engineers and the continuous development of nearly twenty centuries has left us little to go on save conjecture. There are points in that conjecture, however, which are fairly certain. But there seems to have been, from the earliest time, communication between north and south on the lowest crossing of the Thames. Now, the lowest permanent crossing of the Thames, even before a bridge, was in the neighbourhood of London.

The crossing of a river is determined by the hardness of the land upon either bank, as we have seen, more than by any other factor. The lower Thames everywhere had extensive marshes either upon one side or the other, and usually upon both. At Grays, Tilbury, Erith, etc., the hard ground approached right up to one bank, but was always countered by extensive marshes on the other, or by marsh behind gravel, forming a sort of island of hard land which could not be used for continuous travel.

The first good crossing-place was at Lambeth, and it is generally assumed that the earliest of all the tracks took the stream here, for the alignment of the main approach from Kent through Canterbury, Rochester, and Shooters’ Hill does not point at the centre of London, but at Lambeth. This, it is presumed, was the track followed by what is now Park Lane, and so ultimately north-westward by the Edgware Road and its continuations to Chester, with a branch thrown off through the pass between the marshes of the Mersey and the Pennine range in the district of Manchester, and so on through Lancashire. But at some very early stage there was established a crossing below Lambeth in the neighbourhood of London Bridge, even before that bridge came into existence. It is true that there is here a belt of marsh on the right bank, but the considerable gravelly hill on the left, or north, bank there would give an opportunity not to be lost. It had three great advantages: it was a large area of dry land for settlement; it had defences all round it—marshy land to the north, the Fleet to the west, the Lea to the east; it had a considerable area for the drawing up of boats, and a steep shore for wharfage. Under these conditions, whenever men could first construct a causeway it would have been worth while to have been at that labour across the Southwark marshes in order to establish a permanent crossing by ferry, and later by a bridge, upon the site of London Bridge. At any rate, from that centre—London Bridge—at some very early period you get trackways radiating.

There is the main one, in the first place, through Canterbury to Dover and the Kentish ports. Next, there is the eastern one to Colchester, along which the chief Roman invasion marched to the capture of that town, which was the capital of the enemy.

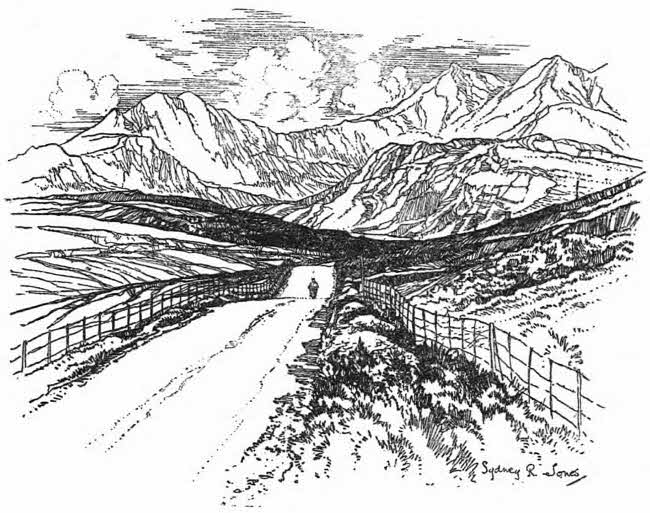

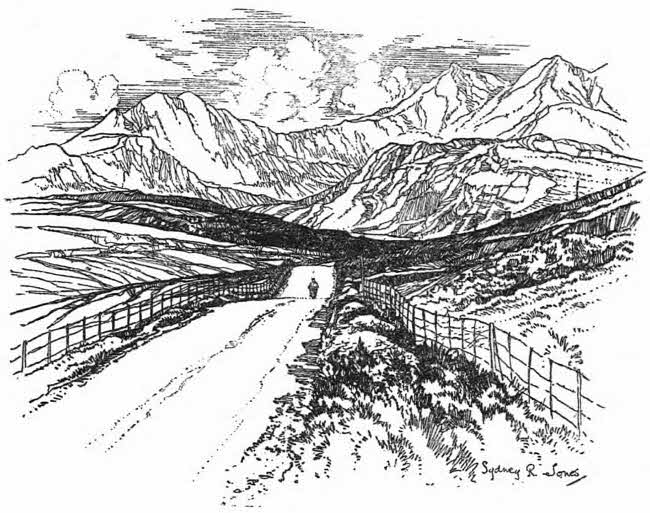

WELSH SECTION, HOLYHEAD ROAD

iii

Next, we may presume (for evidence is lost, especially under the later Roman work) there was a track towards the centre of Norfolk. Next there was some great road going northward east of the Pennines, following the dry land which skirts the Fens and reaching the great fertile plain of York, and so on northward through Durham up to the crossings of the Tyne. Where this original main track went we cannot say. We know the trace of the Roman road which followed it. We may presume that the divagations and modifications of this road of the Dark Ages and the Middle Ages, which ultimately built up our main road to the north, reverted in some degree to the original track. But the whole thing is guess-work. One thing seems fairly certain: this eastern road to the north (the twin to the great north-western road by Chester to Lancashire) must have split about half way to York, one branch making directly to the plain of York itself, the other obviously running along the inevitable ridge which points right north through Lincolnshire to the Humber. There is here no bridge possible. It is not too broad for a ferry. But though the Roman road, superseding the earlier trackway, went on northward, it is a fair guess that the original trackway stopped at the river.

Of cross roads we have fragments, of course, in the Pennines, but we know nothing of their history. It is clear that the main cross communications between the peopled area of the Yorkshire Plain and that of the Lancashire Plain must have gone over by Shipley—the obvious gap in the chain. But more we cannot tell. That is the natural way, and there was, so to speak, no avoiding it. What was mainly used further south we cannot tell. It was a tangled land. There is no clear and certain trace of cross communications which must have existed across the Midlands south of Trent. We do not know what great patches of wood may here have determined the windings of an original road. There are no serious obstacles (it is high land and dry, with no marshes or large watercourses), but there was less reason for continual traffic here from east to west than there was for traffic from north to south; therefore there was less “potential” than was created by the traffic on cross communications further south.

The original system of tracks radiating from Salisbury Plain was simple. They led, in radiating lines straight and curved, directly to the lower Thames, to the ports of the Channel, to the southern estuaries, to the north-east—that is, to the Wash—and to the north direct by the Cotswolds. But true cross communication was lacking to this set, and was provided by the great road from the Exe to the Humber, which still survives in the form of the Fosse Way. It runs throughout the whole of our history, from very long before the first records nearly to the present day, and is to-day traceable throughout, and used in many places as a hard road. This main track was one of the dominant factors in the character of English travel. It has decayed under modern conditions because its “potential” has gone. There is no driving power to-day urging travel from south-west to north-east, and it is only in partial experiments and the linking up of separate lines that even our railway system serves that end. But before modern times the Fosse Way played a very great part. For some reason there was a perpetual necessity for passing from the south-west—Devon and Dorset—to the north-east coast. Two permanent potentials, that between north and south and that between east and west, help to explain the Fosse Way.

England has always tended to fall into two cross divisions—a northern and a southern one, separated at first by climate (the northern more rude, the southern more gentle), then by agricultural conditions, the northern far less peopled, the southern more peopled and more wealthy; and to an eastern and western division separated by type of landscape, to some extent by climate, always to some extent by soil, difference in race, emphasized whenever an invasion came from the Welsh lands on the one side or from the North Sea on the other. The Fosse Way broke both those cross divisions and was a sort of “reinforcement” (as they say in modern concrete), taking the strain of cross tension across the island.

iv

In this short sketch of what were in some cases certainly, in others only presumably, the original British main tracks we have to note three factors which have always determined travel in Britain: the centres of internal economic production, the ports, and the Channel crossings.

Before the modern industrial system the economic centres of production were the wheat lands, and these were the open land of which Winchester was the centre, the Dorchester centre, Somerset, certain separate centres in the Midlands (separated by great woods which have disappeared and their exact site not certain), the Cheshire Plain, the Lancashire Plain, the great Yorkshire Plain, and last, and most important of all, East Anglia—the central Eastern plain (Essex in particular) was the granary of the early time in England. Tracks connected all these places: they also connected the centres of population with the ports. Every one of the tracks makes ultimately from port to port. You have a connection through London (earlier perhaps, as we have seen, through Lambeth) between the port of Kent and the north-western ports (of which Chester is the great original example and Liverpool the modern); between the north-eastern ports of the Humber and the Tyne, and the south-western ports at Southampton Water and Poole (which was of great early importance, and whence we shall find a Roman road starting). Further west the mouth of the Exe was a more important approach to Britain in the past than it is now. You have also the estuary of the Severn, ill provided with natural harbours but forming in its upper reaches a harbour of its own, with the peculiar advantage of the lower Avon, with a secure pool at Bristol approached by the curious and exceptional gorge at Clifton.

Lastly, you have the great port formed by the crossing place at London, made, as we have seen, by the tendency of early travel, right up to the appearance of railways, to penetrate a country as far as possible by its waterways and to carry cargoes well inland, because water carriage was so much cheaper than land transport.

The third factor—that of river crossing—also has its effect, though a lesser one, upon the trace of the old British ways. If, for instance, you carry along any one of the tracks which follow the chalk you will see how carefully the water crossings were picked. It is the characteristic of chalk that the rivers lie transverse to it, cutting gorges through the hills, and each of these crossing places was chosen where hard land approached from either side. The chalk (and the sand associated with it) provides at certain points in the valleys twin spurs approaching the water on either side; hence you have the track along the north downs crossing the Wey at St. Catherine’s Chapel (and alternatively by Guildford); and, again, the Mole at Pixham, near Dorking, and the Medway at Snodland (with an alternative at Rochester). The southern track along the Hampshire and Sussex Downs takes the Arun at a similar advantage and opportunity at Houghton, and alternatively at Arundel. It takes the Adur at Bramber, the Ouse at Lewes.

This vague sketch of the old trackways is all that we can lay down so far as their main lines are concerned, and it is very imperfect, but we must bear it in mind in order to understand the Roman system, which was largely based upon those trackways and which superseded them.

There was one kind of soil, and one only, which could compete with the chalk as good going for primitive travel, and that was sand. Had we sand in continuous lines in Britain it would have given a dry passage for the trackways, and here and there advantage is taken of it by such trackways. But sand, in point of fact, is not to be found in these continuous lines. It comes in patches, and hence we cannot talk of any one of the great trackways as dependent upon a sandy soil. The chief exception that I can call to mind in this respect is the run of the old Pilgrims’ Way—a prehistoric track from the neighbourhood of Farnham to the crossing of the Mole, near Dorking. Though chalk lay on the main direction, it seems to have preferred the southern dry sand to the chalk immediately north of it, and it keeps to the sand until the cessation of that formation a short distance west of the Mole. There is here a curious piece of political geology which has been, I think, of great effect upon the history of England. Had the ridges of sand through the weald of Sussex been continuous, the weald would have been developed early. Its iron industry would have furnished a basis for export, and it would have become one of the centres of population. There are ridges of sand which you can trace all the way through the weald from close by the Hampshire chalk in the neighbourhood of Midhurst right away to the valley of the Rother. But they are not continuous, and the interruptions are formed of deep clay, impossible to pass in winter. The result of that lack of continuity has been that no such track ever developed through the weald of Sussex. Sussex, therefore, owing to the stiff clay of its weald, remained cut off from the rest of England, and that throughout all the Dark Ages. It falls out of the national history. Indeed, the linking up of Sussex with the north was only effected by the Romans at the cost of great labour through the artificial causeway of the Stane Street between Chichester and London; and after the breakdown of western civilization in the fifth century there was no regular approach to the southern coast from the Thames valley in a direct line. The traffic either went westward down towards Southampton, Hampshire, Dorset, and Devon or eastward to the Straits of Dover. The Norman Conquest and the rule of the Angevins restored Sussex to something of its rightful place in English communications because the coast of that county lay immediately opposite the centre of the foreign region which then governed England, but the interlude was not lengthy. In the later Middle Ages and on to quite modern times (to the middle of the eighteenth century) the interruption due to the clay made itself felt again, and only the railway and great increase of population have been able between them to restore direct and frequent communication between the Thames valley and this part of the southern coast.