missiles. However, deep snow reduces their bursting radius, making them approximately 40 percent less effective. The rugged nature of the terrain may afford added protection for defending forces; therefore, large quantities of HE may be required to achieve the desired effects against enemy defensive positions.

• Variable time (VT) or time fuzes should be used in deep snow conditions and are particularly effective against troops on reverse slopes.

There are some older fuzes that may prematurely detonate when

fired during heavy precipitation (M557 and M572 impact fuzes and

M564 and M548 time fuzes).

• Smoke, DPICM, and illuminating fires are hard to adjust and maintain due to swirling, variable winds and steep mountain slopes.

Smoke (a base-ejecting round) may not dispense properly if the canis-ters become buried in deep snow. In forested mountains, DPICMs

may get hung up in the trees. These types of munitions are generally more effective along valley floors.

• Using the artillery family of scatterable mines (FASCAM) and Cop-perhead is enhanced when fired into narrow defiles, valleys, and

roads. FASCAM may lose their effectiveness on steep terrain and in deep snow. Melting and shifting snow may cause the anti-handling

devices to detonate prematurely the munitions, however, very little settling normally occurs at temperatures lower than 5 degrees Fahrenheit. Remote antiarmor mine system (RAAMS) and area denial ar-

tillery munitions (ADAM) must come to rest and stabilize within 30

seconds of impact or the submunitions will not arm, and very uneven terrain may keep the ADAM trip wires from deploying properly.

MORTARS

3-13. Mortars are essential during mountain operations. Their high angle of fire and high rate of fire is suited to supporting dispersed forces. They can deliver fires on reverse slopes, into dead space, and over intermediate crests, 3-5

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

and, like field artillery, rock fragments caused by the impact of mortar rounds may cause additional casualties or damage.

3-14. The 60mm mortar is an ideal

supporting weapon for mountain combat

because of its portability, ease of

concealment, and lightweight ammunition.

The 81mm mortar provides longer range

and delivers more explosives than the 60mm

mortar. However, it is heavier and fewer

rounds (usually no more than two per

soldier) can be man-packed. The 120mm

mortar may be more desirable in some

situations, since they can fire either white

phosphorous (WP) or HE at greater ranges

than lighter mortars and have a

significantly better illumination capability.

However, because of the weight of these mortars and their ammunition, it may be necessary to transport fewer of them into mountainous terrain and use the remaining gun crews as ammunition bearers, or position them close to a trail network in a valley or at lower elevations. The second technique may be satisfactory if the movement of the unit can be covered and sufficient firing positions exist.

AIR SUPPORT

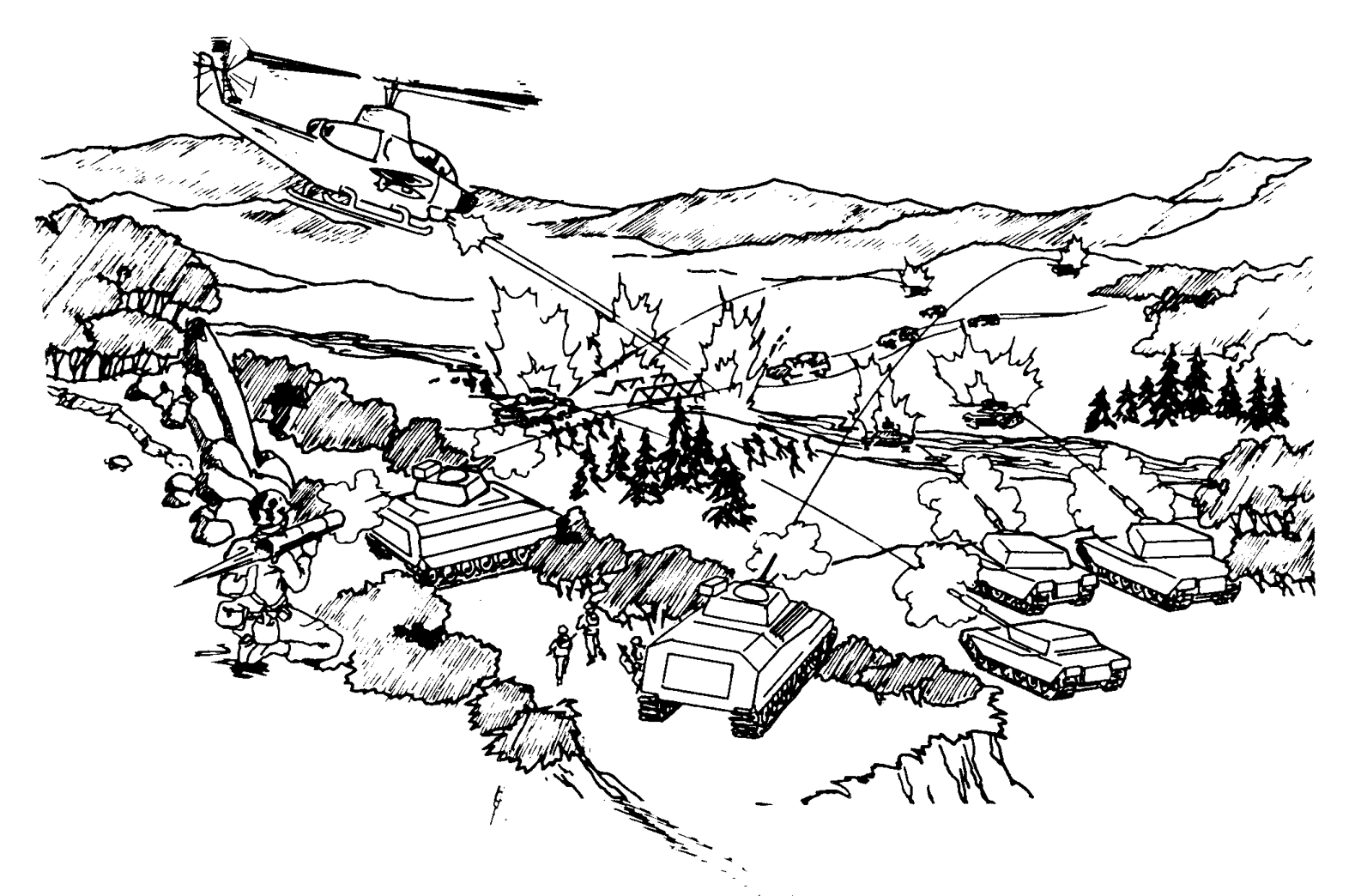

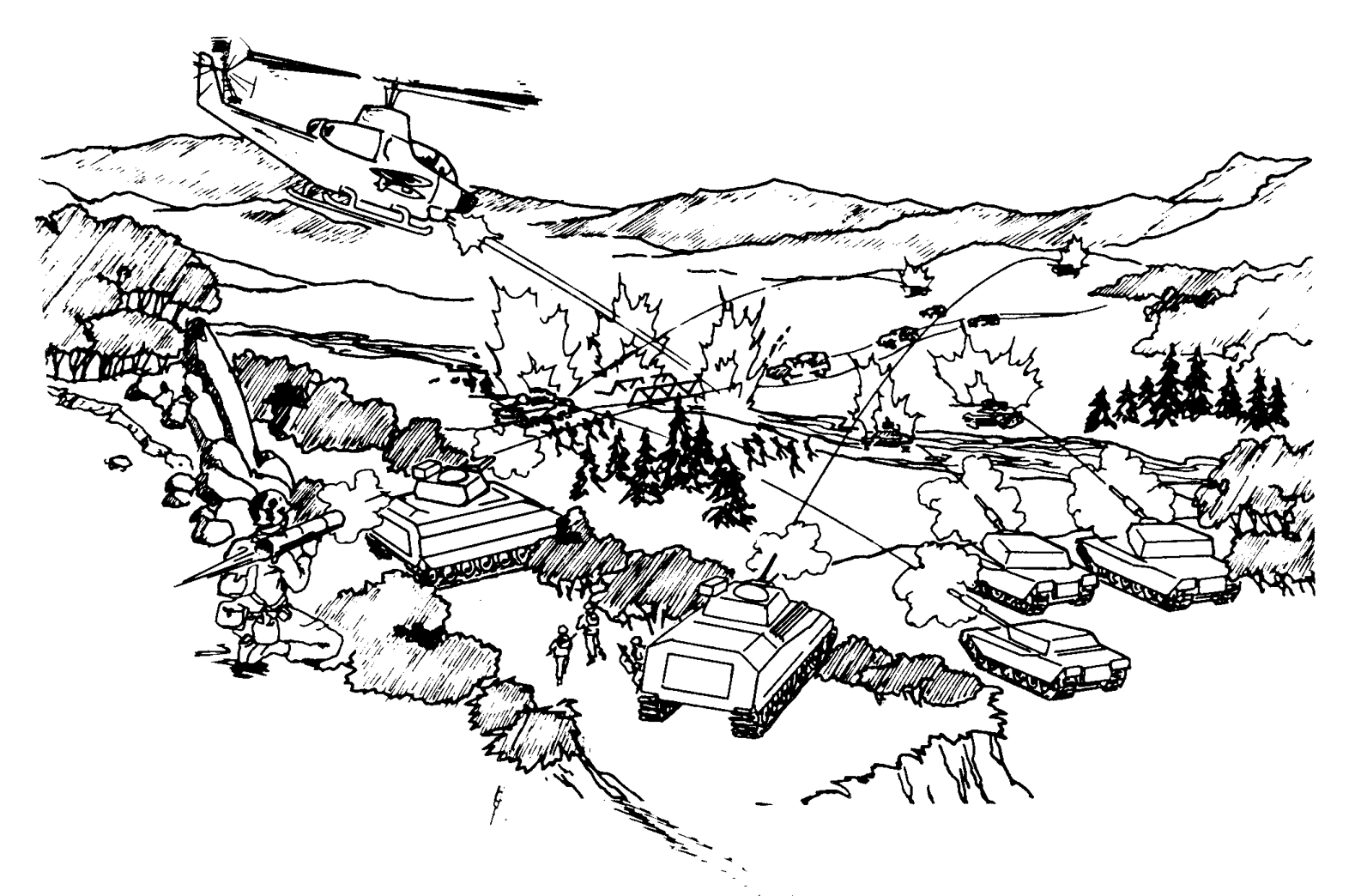

3-15. Air interdiction and close air support operations can be particularly effective in mountains, since enemy mobility, like ours, is restricted by terrain.

Airborne forward air controllers and close air support pilots can be used as valuable sources of information and can find and designate targets that may be masked from direct ground observation. Vehicles and personnel are particularly vulnerable to effective air attack when moving along narrow mountain roads. Precision-guided munitions, such as laser-guided bombs, can quickly destroy bridges and tunnels and, under proper conditions, cause landslides and avalanches to close routes or collapse on both stationary and advancing enemy forces. Moreover, air-delivered mines and long-delay bombs can be employed to seriously impede the enemy’s ability to make critical route repairs. Precision-guided munitions, as well as fuel air explosives, can also destroy or neutralize well-protected point targets, such as cave entrances and enemy forces in defilade.

3-16. Low ceilings, fog, and storms common to mountain regions may degrade air support operations. Although, global positioning system (GPS) capable aircraft and air delivered weapons can negate many of the previous limitations caused by weather. Terrain canalizes low altitude air avenues of approach, limiting ingress and egress routes and available attack options, and increasing aircraft vulnerability to enemy air defense systems. Potential targets can hide in the crevices of cliffs and the niches of mountain slopes, and on gorge floors. Hence, pilots may be able to detect the enemy only at short distances, requiring them to swing around for a second run on the target and _______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 3

giving the enemy more time to disperse and seek better cover. Additionally, accuracy may be degraded due to the need for pilots to divert more of their attention to flying while simultaneously executing their attack.

ELECTRONIC WARFARE

3-17. The ability to use electromagnetic energy to deceive the enemy, locate his units and facilities, intercept his communications, and disrupt his command, control, and target acquisition systems remains as important in the mountains as elsewhere. The effects of terrain and weather on electronic warfare (EW) systems are often a result of the effects on the components of those systems (particularly soldiers, communications, and aviation). Although a number of the effects are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this manual (and in applicable FMs and TMs), for ease some of the more common degrading effects of the mountainous environment on the components of electronic warfare systems are described in Figure 3-1 on page 3-8.

SECTION II – PROTECTION OF THE FORCE

AIR DEFENSE ARTILLERY

3-18. The severe mountain environment requires some modification of air defense employment techniques. Suitable positions are scarce and access roads are limited. In some instances, supporting air defense weapons may not be able to deploy to the most desirable locations. Consequently, the man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) may be the only air defense weapon capable of providing close-in protection to maneuver elements.

3-19. Mountain terrain tends to degrade the electronic target acquisition capabilities of air defense systems. This degradation makes it more difficult for the air defense planner to locate and select position to provide adequate coverage for the force, and increases the importance of combined arms for air defense (CAFAD) and passive air defense measures (see FM 3-01.8). Individual and crew-served weapons can mass their fires against air threats. The massed use of guns in local air defense causes enemy air to increase their standoff range for surveillance and weapons delivery, and increase altitude in transiting to and from targets. These reactions may make the enemy air more vulnerable to air defense artillery (ADA).

3-20. Enemy aircraft will probably use defiles and valleys in mountainous terrain for low-altitude approaches to take advantage of terrain masking of radar. Congested roads and trails, and their junctions, may become lucrative targets for enemy air strikes. Enemy pilots may avoid early detection by using terrain-clearance or terrain-following techniques to approach a target.

Rugged mountain terrain degrades air defense detection, but, at the same time, mountain ridges and peaks tend to canalize enemy aircraft. Detailed terrain analysis, coupled with predictive analysis to identify probable enemy air avenues of approach, aids in effective site selection.

3-7

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

ENVIRONMENTAL

FACTORS

T

C

E

EW

L

R S

W T

F

R

REMARKS

COMPONENT

O

A N

I

E

O

R

U

I

O N M

G

A

D

N W D P

I

S

N

■

Clouds, fog, precipitation, and terrain affect

visibility and observation.

Soldiers1

✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ■

Precipitation, temperature, and the rugged terrain

affect soldier performance and ability to operate

systems.

■

Extreme cold, combined with rugged terrain,

Electronics and-

increases fragility and breakage.

wire/cables2

✔ ✔ ✔

✔ ✔ ■ Precipitation and humidity affect electronic com-

ponents.

■

Strong winds damage or prevent erection.

■

Precipitation and cold create ice, causing break-

age (increased load and wind resistance) and

Antennas2

✔ ✔ ✔

✔

reduce effectiveness.

■

Terrain affects masking and line-of-sight

restrictions.

■

Clouds, fog, and precipitation degrade visibility

and may prevent aircraft from flying under visual

flight rules (VFR), precluding missions requiring

aircraft landing at unimproved mountain LZs.

Aircraft3

✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ■ Cold and precipitation lead to icing, which im-

pedes lift.

■

Compartmented terrain affects flight routes and

target acquisition.

Vehicles

✔ ✔

✔ ✔ ■

Rain, snow, and rugged terrain decrease mobility.

■

Wind increases background noise, reducing

efficiency.

■

Terrain affects masking and line-of-sight

Radars/ Sensors

✔ ✔ ✔ ✔

✔

restrictions.

■

Fog and precipitation decrease infrared and

electro-optical systems effectiveness.

■

Terrain reduces effectiveness and battery life –

Batteries

✔

some systems may not even work under reduced

power.

1

See Chapter 1 (Effects on Personnel)

2

See Chapter 2 (Communications)

3

See Chapter 4 (Helicopters) and the Previous Section (Air Support) Figure 3-1. Effects of the Mountainous Environment on EW Systems 3-21. Movement to and occupation of positions in mountainous terrain require additional time. Planners must consider slope (pitch and roll), site preparation, and access route improvement prior to movement. Bradley Stinger fighting vehicle (BSFV) units often are unable to accompany small, lightly equipped maneuver elements, and may be restricted to supporting elements in more accessible areas of the battlefield. Avenger fire units can be sling-loaded by heavy lift aircraft and MANPADS airlifted into otherwise

_______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 3

inaccessible positions.

However, equipment

emplaced by helicopters

is resupplied and

repositioned by the

same means. When

moving dismounted,

MANPAD teams are

limited to one missile

per soldier, unless other

members of the unit are

tasked to carry

additional missiles.

3-22. Because of terrain masking of radars and the difficulty in establishing line-of-sight communications with the Sentinel or light and special division interim sensor (LSDIS) radar, early warning for short-range air defense (SHORAD) systems may be limited. Soldiers must maintain continuous visual observation, particularly along likely low-level air avenues of approach.

Therefore, when possible, Sentinel or LSDIS radars should be emplaced on the highest accessible terrain that provides the best air picture for target detection and early warning, not necessarily peaks and summits.

ENGINEER OPERATIONS

3-23. Engineer combat support requirements increase in mountainous terrain because of the lack of adequate cover, the requirement for construction of field fortifications and obstacles, and the need to breech or reduce enemy obstacles. With such an enormous multitude of tasks, effective command and control of engineer assets is essential for the optimal utilization of these relatively scarce resources (see also the discussion of engineer augmentation and employment in the mobility section of Chapter 4).

3-24. Digging fighting positions and creating temporary fortifications above the timberline is generally difficult because of thin soil with underlying bed-rock. As described in Chapter 2, boulders and loose rocks may be used to build hasty, aboveground fortifications. Well-assembled positions constructed in rock are strong and offer good protection, but they require considerable time and equipment to prepare.

3-25. Engineers assist maneuver units with light equipment and tools carried in or brought into position by ground vehicles or helicopters. Bulldozers, armored combat earthmovers (ACEs), and small emplacement excavators

(SEEs) can be used in some situations to help prepare positions for command bunkers and crew-served weapons. They can also be used to prepare positions off existing roads for tanks, artillery, and air defense weapons. Conventional equipment and tools are often inadequate in rocky terrain, and extensive use of demolitions may be required. In the mountains, a greater number of engineer assets will be devoted to maintaining mobility and maneuver and unit commanders should assume that available engineer support will be limited to 3-9

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

assist them with their survivability efforts. To enhance survivability and mobility a minimum of two soldiers per maneuver platoon should be capable of using standard demolitions.

NBC PROTECTION

3-26. Terrain and weather dictate a requirement for a high degree of nuclear, biological, and chemical (NBC) defense preparedness in mountainous areas.

Due to limited mobility, viable tactical positions, and limited communication abilities, friendly units must be self-sufficient in protecting themselves against NBC weapon system effects.

3-27. Wearing mission-oriented protective posture (MOPP) gear at high elevations, when possibly combined with altitude sickness, increased dehydration, and increased physical exertion, degrades performance and increases the likelihood of heat casualties. Commanders should make every effort to keep soldiers out of MOPP gear until intelligence indicators reveal that an NBC attack is imminent or it is confirmed that a hazard actually exists (see FM 3-11.4 for a discussion on vulnerability analysis). When precautions must be taken against hazards, commanders must make decisions early and allow extra time for tactical tasks. Commanders should also refer to TC 3-10 for greater detail on tactics, techniques, and procedures necessary to operate under NBC conditions.

NUCLEAR

3-28. A mountainous environment can amplify or reduce the effects of and distort the normal circular pattern associated with nuclear blasts. The irregular patterns reduce the accuracy of collateral damage prediction, damage estimation, and vulnerability analysis.

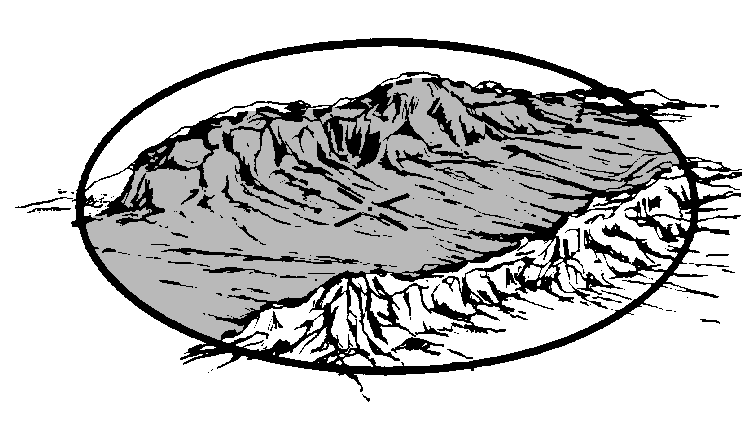

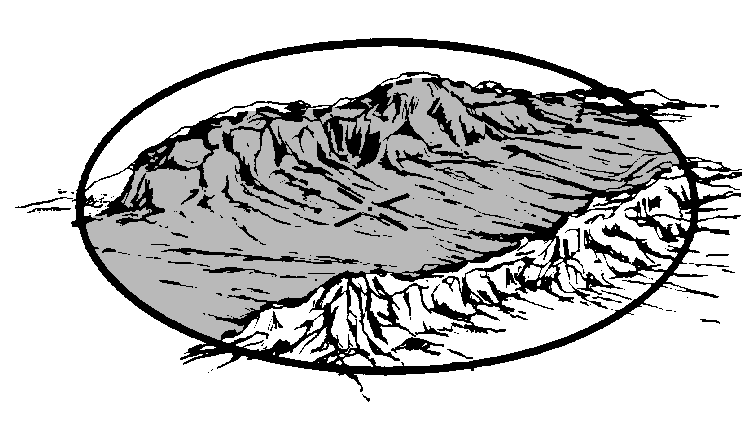

3-29. Air blast effects are amplified on the burst side of mountains (see Figure 3-2). Mountain walls reflect blast waves that can reinforce each other, as well as the shock front. Therefore, it is possible that both overpressure and dynamic pressure, and their duration will increase. An added danger is the creation of rockslides or avalanches. A small yield nuclear weapon detonated 30 kilometers or more from the friendly positions may still cause rockslides and avalanches, and easily close narrow roads and canalized passes. On the other hand, there may be little or no blast effects on the side of the mountain away from the burst.

3-30. Hills and mountains block thermal radiation, and trees and other foliage reduce it. Low clouds, fog, and falling rain or snow can absorb or scatter up to 90 percent of a burst's thermal energy. During colder weather, the heavy clothing worn by soldiers in the mountains provides additional protection. However, the reflection from snow and the thin atmosphere of higher elevations may increase the effects of thermal radiation. Snow and ice melted by thermal radiation can result in flash flooding.

3-31. Frozen and rocky ground may make it difficult to construct shelters for protection from the effects of nuclear weapons. However, natural shelters

_______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 3

such as caves, ravines, and cliffs provide some protection from nuclear effects and contamination. In some instances, improvised shelters built of snow, ice, or rocks may be the only protection available. The clear mountain air extends the range of casualty-producing thermal effects. Within this range, however, the soldiers' added clothing reduces casualties from these effects.

Typical Radius of

Effect on Flat

Terrain

Probable

Limit of

Effects

Caused by

the Terrain

Figure 3-2. Effects of Mountains on Radiation and Blast

3-32. In mountainous regions, the deposit of radiological contamination is very erratic in speed and direction because of variable winds. Hot spots may occur far from the point of detonation, and low-intensity areas may occur very near it. Limited mobility makes radiological surveys on the ground difficult, and the difficulty of maintaining a constant flight altitude makes air surveys highly inaccurate. Additionally, melting snow contributes to the residual radiation pattern. After a nuclear detonation, streams should be checked for radiation contamination before using them for drinking or bathing. As with the other effects, the pattern of initial and induced nuclear radiation may be modified by topography and the height of the burst.

BIOLOGICAL

3-33. Most biological pathogens and some toxins are killed or destroyed by the ultraviolet rays in sunlight. Above the timberline, there is little protection from the sun; thus, the effectiveness of a biological attack may be reduced.

Downwind coverage may be greater because of the frequent occurrence of high winds over mountain peaks and ridges. Additionally, inversion conditions favor the downwind travel of biological agents through mountain valleys. Typically, winds flow down terrain slopes and valleys at night and up valleys and sunny slopes during the day. The effects of mountainous terrain and rapidly changing wind conditions on the ability to predict and provide surveys of contamination for biological agents are similar to that for nuclear radiation.

3-11

FM 3-97.6 ________________________________________________________________________________

3-34. Temperatures and humidity also affect the survivability of biological agents. Generally, cool temperatures favor survival, and higher humidity increases the effectiveness of the agents. Extreme cold weather and snow deposited over a biologically contaminated area can lengthen the effective period of the hazard by allowing the agent to remain alive but dormant until it is disturbed or the temperature rises. If the use of biological agents is known or suspected, commanders should ensure that soldiers pay added attention to personal hygiene and consume only purified/treated water.

CHEMICAL

3-35. Wind and terrain can also cause the effectiveness of chemical agents to vary considerably. Depending on conditions, effects can be significantly enhanced or almost ineffective. High winds and rugged terrain cause chemical agent clouds to act in a manner similar to radioactive fallout. Inversions in mountain valleys may also effectively cap an area, slowing the dissipation rate. Because of terrain and winds, accurate prediction of the downwind travel of toxic agent clouds is difficult.

3-36. In mountain warfare, chemical munitions are likely to be delivered by air. The generally cooler daytime temperatures in mountainous terrain slow the evaporation process, thus allowing a potential contamination hazard to remain active longer. Midday temperatures favor using persistent or blister-type agents, since nonpersistent agents dissipate too rapidly to cause any effect and unsupervised personnel are more likely to remove protective clothing for comfort.

3-37. The actions to protect against chemical agents in the mountains are not significantly different than from the requirements in less mountainous terrain. However, in extreme cold weather, survey and monitoring is often limited to the individual team mission, the FOX system may be limited to roads and trails, and the detection of vapor hazards is limited when the temperature falls below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Decontamination may be more difficult due to freezing conditions, and the virulency period of contamination hazard for persistent agents may increase.

SMOKE AND OBSCURANTS

3-38. Smoke operations in mountainous areas are characterized by difficulties encountered due to terrain and wind. Inadequate roads enhance the military value of existing roads, mountain valleys, and passes and add importance to the high ground that dominates the other terrain. Planners can use smoke and flame systems to deny the enemy observation of friendly positions, supply routes, and entrenchments, and degrade their ability to cross through tight, high passes and engage friendly forces with direct and indirect fires.

3-39. Thermally induced slope winds that occur throughout the day and night increase the difficulty of establishing and maintaining smoke operations, except in large and medium sized valleys. Wind currents, eddies, and turbulence in mountainous terrain must be continuously studied and observed, and their skillful exploitation may greatly enhance smoke operations rather than _______________________________________________________________________________ Chapter 3

deter them. Smoke screens may be of limited use, due to enemy aerial observation, to include UAVs, and observation by enemy forces located on high ground. Smoke units may be required to operate for extended periods with limited resupply unless petroleum, oils, and lubricants (POL) supplies are emplaced in hide positions with easy access.

3-13

Chapter 4

Maneuver

The mountain environment requires the modification of tactics, techniques, and procedures. Mountains limit mobility and the use of large forces, and restrict the full use of sophisticated weapons and equipment.

These limitations enable a well-

CONTENTS

trained and determined enemy

to have a military effect

Section I – Movement and Mobility............. 4-2

Mounted Movement.................................. 4-3

disproportionate to his numbers

Dismounted Movement ............................ 4-7

and equipment. As such,

Mobility ...................................................... 4-8

mountain campaigns are

Special Purpose Teams ......................... 4-10

normally characterized by a

Section II – Offensive Operations ............. 4-16

series of separately fought

Planning Considerations ....................... 4-16

battles for the control of

Preparation .............................................. 4-17

dominating ridges and heights

Forms of Maneuver ................................ 4-18

that overlook roads, trails, and

Movement to Contact ............................. 4-19

other potential avenues of

Attack ....................................................... 4-20

approach. Operations generally

Exploitation and Pursuit ........................ 4-22

focus on smaller-unit tactics of

Motti Tactics............................................ 4-23

Section III – Defensive Operations............ 4-25

squad, platoon, company, and

Planning Considerations ....................... 4-25

battalion size. Because access to

Preparation .............................................. 4-26

positions is normally difficult,

Organization of the Defense .................. 4-27

adjacent units often cannot

Reverse Slope Defense .......................... 4-29

provide mutual support and

Retrograde Operations........................... 4-30

reserves cannot rapidly deploy.

Stay-Behind Operations......................... 4-31

Attacks in extremely rugged

4-1

FM 3-97.6

terrain are often dismounted, with airborne and air assaults employed to seize high ground or key terrain and to encircle or block the enemy's retreat. While the mountainous terrain is usually thought to offer the greatest advantage to the defender, the attacker can often gain success with smaller forces by effectively using deception, bold surprise actions, and key terrain.

Although mountains often increase the need to employ light forces, commanders should not be misled into believing that this environment is the sole domain of dismounted units. On the contrary, the integrated use of mounted and dismounted forces in a mo