CHAPTER IX

THE ISLANDS OF THE BLEST

Souls on Islands—Wells of Life and Trees or Plants of Life in China, Ancient Egypt, Babylonia, &c.—How Islands were Anchored—The Ocean Tortoise—A Giant’s Fishing—The Mystery of Fu-sang—Island of Women—Search for Fabled Isles—Chinese and Japanese Stories—How Navigation was Stimulated—Columbus and Eden—Water of Life in Ceylon, Polynesia, America, and Scotland—Delos, a Floating Island—Atlantis and the Fortunate Isles—Celtic Island Paradise—Apples and Nuts as Food of Life—America as Paradise—The Indian Lotus of Life—Buddhist Paradise with Gem-trees—Diamond Valley Legend in China and Greece—Luck Gems and Immortality.

The Chinese and Japanese, like the Egyptians, Indians, Fijians, and others, believed, as has been shown, in the existence of a floating and vanishing island associated with the serpent-god or dragon-god of ocean. They believed, too, that somewhere in the Eastern Sea lay a group of islands that were difficult to locate or reach; which resembled closely, in essential particulars, the “Islands of the Blest”, or “Fortunate Isles”, of ancient Greek writers. Vague beliefs regarding fabulous countries far across the ocean were likewise prevalent.

In some native accounts these Chinese Islands of the Blest are said to be five in number, and named Tai Yü, Yüan Chiao, Fang Hu, Ying Chou, and P’ēng-lai; in others the number is nine, or ten, or only three. A single island is sometimes referred to; it may be located in the ocean, or in the Yellow River, or in the river of the Milky Way, the Celestial Ho.

The islands are, in Chinese legend, reputed to be inhabited by those who have won immortality, or by those who have been transported to their Paradise to dwell there in bliss for a prolonged period so that they may be reborn on earth, or pass to a higher state of existence.

It is of special interest to note in connection with these islands that they have Wells of Life and Trees or Herbs of Life. The souls drink the water and eat the herb or fruit of the tree to prolong their existence. One Chinese “plant of life” is li chih, “the fungus of immortality”. It appears on Chinese jade ornaments as a symbol of longevity. “This fungus”, writes Laufer, “is a species of Agaric and considered a felicitous plant, because it absorbs the vapours of the earth. In the Li Ki (ed. Couvreur, Vol. I, p. 643) it is mentioned as an edible plant. As a marvellous plant foreboding good luck, it first appeared under the Han Dynasty, in 109 B.C., when it sprouted in the imperial palace Kan-tsʼüan. The emperor issued an edict announcing this phenomenon, and proclaimed an amnesty in the empire except for relapsing criminals. A hymn in honour of this divine plant was composed in the same year.”1

Like the Red Cloud herb the li chih had evidently a close connection with the dragon-god.

The question arises whether the idea of an island of paradise was of “spontaneous origin” in China, or whether the ancient Chinese borrowed the belief from intruders, or from peoples with whom they had constant trading relations. There is evidence that as far back as the fourth century B.C., a Chinese explorer set out on an expedition to search for the island or islands of Paradise in the Eastern Sea. But it is not known at what precise period belief in the island arose and became prevalent.

The evidence afforded by the ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts is of special interest and importance in connection with the problem of origin. As far back as c. 2500 B.C. “the departed Pharaoh hoped to draw his sustenance in the realm of Re (Paradise)” from “the tree of life in the mysterious isle in the midst of the Field of Offerings”. The soul of the Pharaoh, according to the Pyramid Texts, set out, soon after death, in search of this island “in company with the Morning Star. The Morning Star is a gorgeous green falcon, a solar divinity, identified with Horus of Dewat.” The Egyptian story of the soul’s quest goes on to tell that “this King Pepi … went to the great isle in the midst of the Field of Offerings over which the gods make the swallows fly. The swallows are the Imperishable Stars. They give to this King Pepi the tree of life, whereof they live, that ye (Pepi and the Morning Star) may at the same time live thereof.” (Pyramid Texts, 1209–16). Sinister enemies “may contrive to deprive the king of the sustenance provided for him.…” Charms were provided to protect the fruit of immortality. “The enemy against which these are most often directed in the Pyramid Texts is serpents.” In the Japanese story of the Kusanagi sword, the gem-trees of the Otherworld are protected by dragons.

The Pyramid Texts devoted to the ancient Egyptian King Unis tell that a divine voice cries to the gods Re and Thoth (sun and moon), saying, “Take ye this King Unis with you that he may eat of that which ye eat, and that he may drink of that which ye drink.” The magic well is referred to as “the pool of King Unis”.2 The soul of the Pharaoh also sails with the unwearied stars in the barque of the sun-god, not only by day but by night, and as the Egyptian night sun was green, “the green bed of Horus”, the idea of the floating solar island on the Underworld Nile became fused with that of the island with the Well of Life and the Tree of Life. In the Pyramid Texts the Celestial Otherworld “is”, as Breasted says, “not only the east, but explicitly the east of the sky”.3 Similarly the fabulous continents of the Chinese were situated to the east of the mythical sea.

The Sumerians and early Babylonians had, like the Egyptians, their Islands of the Blest. Gilgamesh, who reaches these islands by crossing the mythical sea, finds dwelling on one of them Ut-napishtim (the Babylonian Noah) and his wife. Ut-napishtim directs the hero to another island on which there is a fountain of healing waters and a magic plant that renews youth. Gilgamesh finds the Plant of Immortality, but as he stoops to drink water from a stream, a serpent darts forth and snatches the plant from him. This serpent was a form of “the Earth Lion” (the dragon).4

The Gilgamesh legend dates back beyond 2500 B.C. Like the Egyptian one enshrined in the Pyramid Texts, it has two main features, the Well of Life and the Tree or Plant of Life, which are situated on an island. The island in time crept into the folk-tales. It was no doubt the prototype of the vanishing island of the Egyptian mariner’s story already referred to.

In the Shih Chi (Historical Record) of Ssŭ-ma Chʼien, “the Herodotus of China”, a considerable part of which has been translated by Professor Ed. Chavannes,5 the three Chinese Islands of the Blest (San, Shen, Shan) are named P’ēng-lai, Fang Chang, and Ying Chou. They are located in the Gulf of Chihli, but are difficult to reach because contrary winds spring up and drive vessels away in the same manner as the vessel of Odysseus was driven away from Ithaca. It is told, however, that in days of old certain fortunate heroes contrived to reach and visit the fabled isles. They told that they saw there palaces of gold and silver, that the white men and women, the white beasts and the white birds ate the Herb of Life and drank the waters of the Fountain of Life. On the island of Ying Chou are great precipices of jade. A brook, the waters of which are as stimulating as wine, flows out of a jade rock. Those who can reach the island and drink of this water will increase the length of their lives. When the jade water is mixed with pounded “fungus of immortality” a food is provided which ensures a thousand years of existence in the body.

Chinese legends tell that the lucky mariners who come within view of the Isles of the Blest, behold them but dimly, as they seem to be enveloped in luminous clouds. When vessels approach too closely, the islands vanish by sinking below the waves, as do the fabled islands of Gaelic stories.

Lieh Tze, alleged to be an early Taoist writer,6 but whose writings, or those writings attributed to him, were forged in the first or second century A.D., has located the islands to the east of the gulf of Chihli in that fathomless abyss into which flow all the streams of the earth and the river of the Milky Way. Apparently this abyss is the Mythical Sea which was located beyond the eastern horizon—a part of the sea that surrounds the world. Into this sea or lake, according to the ancient Egyptian texts, pours the celestial river, along which sails the barque of the sun-god. The Nile was supposed by the Ancient Egyptians to be fed by the waters above the firmament and the waters below the earth. The Pyramid Texts, when referring to the birth of Osiris as “new water” (the inundation), say:

The waters of life that are in the sky come;

The waters of life that are in the earth come.

The sky burns for thee,

The earth trembles for thee.7

In India the Ganges was likewise fed by the celestial Ganges that poured down from the sky.

Lieh Tze’s Islands of the Blest are five in number, and are inhabited by the white souls of saintly sages who have won immortality by having their bodies rendered transparent, or after casting off their bodies as snakes cast off their skins. All the animals on these islands are likewise white and therefore pure and holy. The spirit-dwellings are of gold and jade, and in the groves and gardens the trees and plants bear pearls and precious stones. Those who eat of the fungus, or of perfumed fruit, renew their youth and acquire the power of floating like down through the air from island to island.

At one time the islands drifted about on the tides of ocean, but the Lord of All who controls the Universe, having been appealed to by the Taoist sages who dwelt on the isles, caused three great Atlas-turtles to support each island with their heads so that they might remain steadfast. These turtles are relieved by others at the end of sixty thousand years. In like manner, in Indian mythology, the tortoise Kurma, an avatar of the god Vishnu, supports Mount Meru when it is placed in the Sea of Milk. The Japanese Creator has a tortoise form that supports the world-tree, on the summit of which sits a four-armed god. In China the tortoise had divine attributes. Tortoise shell is a symbol of unchangeability, and a symbol of rank when used for court girdles. The tortoise was also used for purposes of divination.8

A gigantic mythical tortoise is supposed, in the Far East, to live in the depths of ocean. It has one eye situated in the middle of its body. Once every three thousand years it rises to the surface and turns over on its back so that it may see the sun.

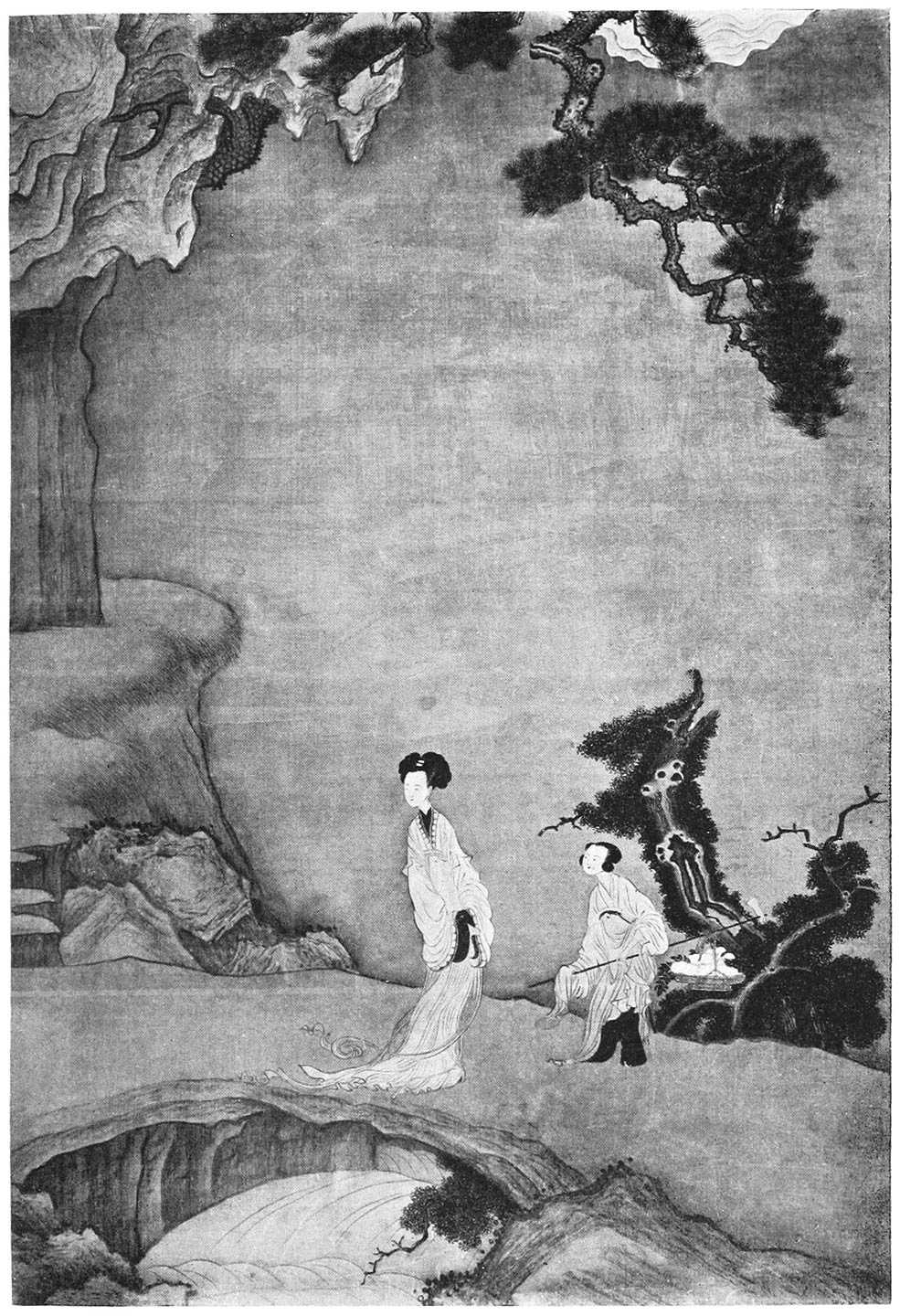

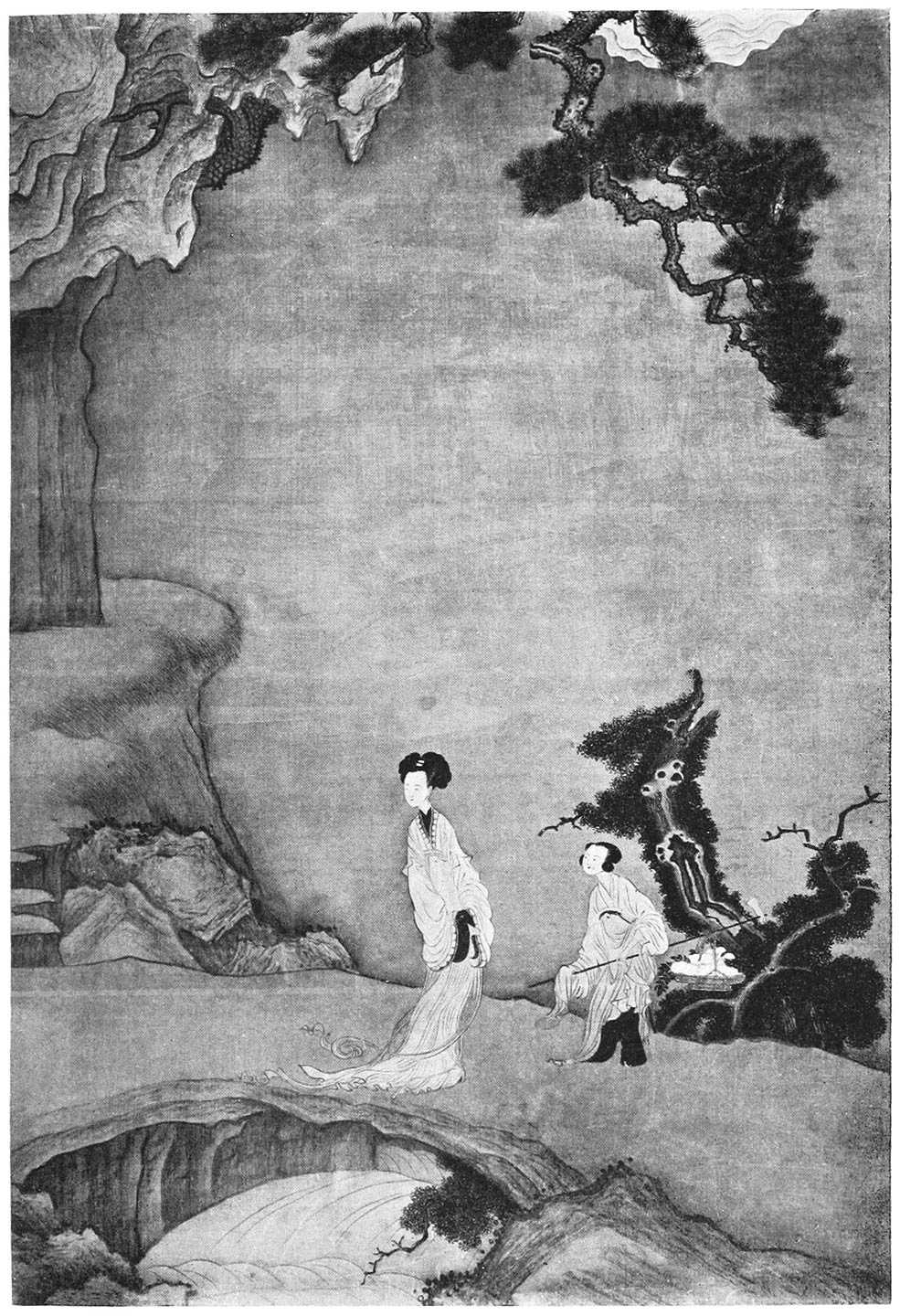

GATHERING FRUITS OF LONGEVITY

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

Once upon a time, a legend tells, the Atlas-turtles that support the Islands of the Blest suffered from a raid by a wandering giant. As the Indian god Vishnu and the Greek Poseidon could cross the Universe at three strides, so could this giant pass quickly from country to country and ocean to ocean. One or two strides were sufficient for him to reach the mythical ocean from the Lung-po mountains. He sat on the mountain summit of one of the Islands of the Blest, and cast his fishing-line into the deep waters.9 The Atlas-turtles were unable to resist the lure of his bait and, having hooked and captured six of them, he threw them over his back and returned home in triumph. These turtles had been supporting the two islands, Tai Yü and Yüan Chiao, which, having been set free, were carried by powerful tides towards the north, where they stranded among the ice-fields. The white beings that inhabited these islands were thus separated from their fellow saints on the other three islands, Fang Hu, Ying Chou, and Pʼēng-lai. We are left to imagine how lonely they felt in isolation. No doubt, they suffered from the evils associated with the north—the “airt” of drought and darkness. The giant and his tribesmen were punished by the Lord of the Universe for this act by having their stature and their kingdom greatly reduced.

On the fabled islands, the white saints cultivate and gather the “fungus of immortality”, as the souls in the Paradise of Osiris cultivate and harvest crops of barley and wheat and dates. Like the Osirian corn, the island fungus sprouts in great profusion. This fungus has not only the power to renew youth but even to restore the dead to life. The “Herodotus of China” has recorded that once upon a time leaves of the fungus were carried by ravens to the mainland from one of the islands, and dropped on the faces of warriors slain in battle. The warriors immediately came to life, although they had lain dead for three days. The “water of life” had similarly reanimating properties.

The famous magician, Tung-fang Shuo, who lived in second century B.C., tells that the sacred islands are ten in number, there being two distinct groups of five. One of the distant islands is named Fu-sang, and it has been identified by different western writers with California, Mexico, Japan, and Formosa. Its name signifies “the Land of the Leaning Mulberry”. The mulberries are said to grow in pairs and to be of great height. Once every nine thousand years they bear fruit which the saints partake of. This fruit adds to their saintly qualities, and gives them power to soar skyward like celestial birds.

Beyond Fu-sang is a country of white women who have hairy bodies. In the spring season they enter the river to bathe and become pregnant, and their children are born in the autumn. The hair of their heads is so long that it trails on the ground behind them. Instead of breasts, they have white locks or hairy organs at the back of their necks from which comes a liquor that nourishes their children. These women, according to some accounts, have no husbands, and take flight when they see a man. A historian who, by the way, gives them husbands, has recorded that a Chinese vessel was once driven by a tempest to this wonderful island. The crew landed and found that the women resembled those of China, but that the men had heads like dogs and voices that sounded like the barking of dogs. Evidently the legends about the fabled islands became mixed up with accounts of the distant islands of a bearded race reached by seafarers.

There are records of several attempts that were made by pious Chinese Emperors to discover the Islands of the Blest, with purpose to obtain the “fungus of immortality”. One mariner named Hsu Fü, who was sent to explore the Eastern Sea so that the fungus might be brought to the royal palace, returned with a wonderful story. He said that a god had risen out of the sea and inquired if he was the Emperor’s representative. “I am,” the mariner made answer.

“What seek ye?” asked the sea-god.

“I am searching for the plant that has the power to prolong human life,” Hsu Fü answered.

The god then informed the Emperor’s messenger that the offerings he brought were not sufficient to be regarded as payment for this magic plant. He was willing, however, that Hsu Fü should see the fungus for himself so that, apparently, the Emperor might be convinced it really existed.

The vessel was then piloted in a south-easterly direction until the Islands of the Blest were reached. Hsu Fü was permitted to land on P’ēng-lai, the chief island, on which was situated the golden palace of the dragon king of ocean. There he saw newly-harvested crops of the “fungus of immortality” guarded by a great brazen dragon of ferocious aspect. Not a leaf could he obtain, however, to bring back to China.

The pious mariner knelt before the sea-god and asked him what offering he required from the Emperor in return for the fungus. He was informed that many youths and girls would have to be sent to P’ēng-lai.

On ascertaining the price demanded by the god for the magic fungus, the Emperor dispatched a fleet of vessels with three thousand young men and virgins. Hsu Fü was placed in command of the expedition. But he never returned again to China. According to some, he and his followers still reside on P’ēng-lai; others assert that he reached a distant land, supposed to be Japan, where he founded a state over which he reigned as king.

Other Chinese Emperors were similarly anxious to discover the fabled islands, and many expeditions were sent to sea. One exasperated monarch is said to have had nearly five hundred magicians and scholars put to death because their efforts to assist him in discovering the islands had proved to be futile.

Another Emperor fitted out a naval expedition which he himself commanded. Each vessel was packed with soldiers who in mid-ocean raised a great clamour, blowing horns, beating drums, and shouting in chorus, with purpose to terrify the gods of ocean and compel them to reveal the location of the Isle of Immortality. In time the dragon-god appeared in his fiercest shape, with the head of a lion and a shark-like body 500 feet in length. The Emperor ordered his fleet to surround the god, who had apparently come with the intention of preventing the ships going any farther. A fierce battle ensued. Thousands of poisoned arrows were discharged against the god, who was so grievously wounded that his blood tinged the sea over an area of 10,000 miles. But despite this victory achieved by mortals, the famous island on which grew the herb of immortality was never reached. On the same night the Emperor had to engage in single combat with the dragon-god, who came against him in a dream. This was a combat of souls, for in sleep, as was believed, the soul leaves the body. The soul of the Emperor fared badly. On the day that followed his majesty was unable to rise from his couch, and he died within the space of seven days.

In Japanese stories the island of P’ēng-lai is referred to as Horaizan. It has three high mountains, on the chief of which, called Horai, grows the Tree of Life. This tree has a trunk and branches of gold, roots of silver, and gem-leaves and fruit. In some stories there are three trees, the peach, the plum, and the pine. The “fungus of immortality” is also referred to. It grows in the shade of one or another of the holy trees, usually the pine. There is evidence, too, of the belief that a “grass of immortality” grew on the sacred island as well as the famous fungus. The life-giving fountain was as well known to the Japanese as it was to the Chinese and others.

A story is told of a Japanese Gilgamesh, named Sentaro, who, being afraid of death, summoned to his aid an immortal saint so that he might be enabled to obtain the “grass of immortality”. The saint handed him a crane made of paper which, when mounted, came to life and carried Sentaro across the ocean to Mount Horai. There he found and ate the life-giving grass. When, however, he had lived for a time on the island he became discontented. The other inhabitants had already grown weary of immortality and wished they could die. Sentaro himself began to pine for Japan and, in the end, resolved to mount his paper crane and fly over the sea. But after he left the island he doubted the wisdom of his impulsive resolution. The result was that the crane, which moved according to his will, began to crumple up and drop through the air. Sentaro was greatly scared, and once again yearned so deeply for his native land that the crane, straightened and strengthened by his yearning, rose into the air and continued its flight until Japan was reached.

Another Japanese hero, named Wasobioye, the story of whose wanderings is retold by Professor Chamberlain,10 once set out in a boat to escape troublesome visitors. The day was the eighth of the eighth month and the moon was full. Suddenly a storm came on, which tore the sail to shreds and brought down the mast. Wasobioye was unable to return home, and his boat was driven about on the wide ocean for the space of three months. Then he reached the Sea of Mud, on which he could not catch any fish. He was soon reduced to sore straits and feared he would die of hunger, but, in time, he caught sight of land and was greatly cheered. His boat drifted slowly towards a beautiful island on which there were three great mountains. As he drew near to the shore, he found, to his great joy, that the air was laden with most exquisite perfumes that came from the flowers and tree-blossoms of that wonderful isle. He landed and found a sparkling well. When he had drunk of the water his strength was revived, and a feeling of intense pleasure tingled in his veins. He rose up refreshed and happy and, walking inland, soon met with Jofuku the sage, known in China as Hsu Fü, who had been sent to the Island of the Blest (P’ēng-lai) by the Emperor She Wang Ti to obtain the “fungus of immortality”, with the youths and virgins, but had never returned.

Wasobioye was taken by the friendly sage to the city of the immortals, who spent their lives in the pursuit of pleasure. He found, however, that these people had grown to dislike their monotonous existence, and were constantly striving to discover some means whereby their days would be shortened. They refused to partake of mermaid flesh because this was a food that prolonged life; they favoured instead goldfish and soot, a mixture which was supposed to be poisonous. The manners of the people were curious. Instead of wishing one another good health and long life, they wished for sickness and a speedy death. Congratulations were showered on any individual who seemed to be indisposed, and he was sympathized with when he showed signs of recovering.

Wasobioye lived on the island for nearly a quarter of a century. Then, having grown weary of the monotonous life, he endeavoured to commit suicide by partaking of poisonous fruit, fish, and flesh. But all his attempts were in vain. It was impossible for anyone to die on that island. In time he came to know that he could die if he left it, but he had heard of other wonderful lands and wished to visit them before his days came to an end. Then, instead of eating poisonous food, he began to feast on mermaid flesh so that his life might be prolonged for many years beyond the allotted span. Thereafter he visited the Land of Shams, the Land of Plenty, &c. His last visit was paid to the Land of Giants. Wasobioye is usually referred to as the “Japanese Gulliver”.

The search for the mythical islands with their “wells of life” and “trees” or “plants of life” is referred to in the stories of many lands and even in history, especially the history of exploration, for the world-wide search for the Earthly Paradise appears to have exercised decided influence in stimulating maritime enterprise in mediæval as well as prehistoric times. Columbus searched for the island paradise in which the “well” and “tree” were to be found. He sailed westward so as to approach the paradise “eastward in Eden”,11 through “the back door” as it were, and wrote: “The saintly theologians and philosophers were right when they fixed the site of the terrestrial paradise in the extreme Orient, because it is a most temperate clime; and the lands which I have just discovered are the limits of the Orient.” In another letter he says: “I am convinced that there lies the terrestrial paradise”.12

As Ellis reminds us, “the expedition which led to the discovery of Florida was undertaken not so much from a desire to explore unknown countries”, as to find a “celebrated fountain, described in a tradition prevailing among the inhabitants of Puerto Rico, as existing in Binini, one of the Lucayo Islands. It was said to possess such restorative powers as to renew youth and the vigour of every person who bathed in its waters. It was in search of this fountain, which was the chief object of their expedition, that Ponce de Leon ranged through the Lucayo Islands and ultimately reached the shores of Florida.”

Ellis refers to this voyage because he found that the mythical island and well were believed in by the Polynesians. He refers, in this connection, to the “Hawaiian account of the voyage of Kamapiikai to the land where the inhabitants enjoyed perpetual health and youthful beauty, where the wai ora (life-giving fountain) removed every internal malady, and every external deformity or paralysed decrepitude, from all those who were plunged beneath its salutary waters”. Ellis anticipates the views of modern ethnologists when dealing with the existence of the same beliefs among widely-separated peoples. He says: “A tabular view of a number of words in the Malayan, Asiatic, or the Madagasse, the American, and the Polynesian languages, would probably show that, at some remote period, either the inhabitants of these distant parts of the world maintained frequent intercourse with each other, or that colonies from some one of them originally peopled, in part or altogether, the others”. He adds, “Either part of the present inhabitants of the South Sea Islands came originally from America, or tribes of the Polynesians have, at some remote period, found their way to the (American) continent”.13

W. D. Westervelt, in his Legends of Old Honolulu, heads his old Hawaiian story “The Water of Life of Ka-ne”, which he himself has collected, with the following extract from the Maori legend of New Zealand:

When the moon dies, she goes to the living water of Ka-ne, to the water which can restore all life, even the moon to the path in the sky.

In the Hawaiian form of the legend the hero, who found the water so that his sick father, the king, might be cured, met with a dwarf who instructed him where to go and what to do.

A russet dwarf similarly figures in the Gaelic story of Diarmaid’s search for the cup and the water of life so that the daughter of the King of Land-under-Waves might be cured of her sickness. This dwarf takes the Gaelic hero across a ferry and instructs him how to find the cup and the water.14

The Polynesians’ ghosts went westward. In their Paradise was a bread-fruit tree. “This tree had two branches, one towards the east and one towards the west, both of which were used by the ghosts. One was for leaping into eternal darkness into Po-pau-ole, the other was a meeting-place with the helpful gods.”15 Turner tells that “some of the South Sea Islanders have a tradition of a river in their imaginary world of spirits, called the ‘water of life’. It was supposed that if the aged, when they died, went and bathed there, they became young and returned to earth to live another life over again.”16 Yudhishthira, one of the heroes of the Aryo-Indian epic the Mahábhárata, becomes immortal after bathing in the celestial Ganges.17 In the Æneid, the hero sees souls in Paradise drinking of the water of Lethe so that they may forget the past and be reborn among men.

Sir John de Mandeville, the fourteenth-century traveller and compiler of traveller’s stories, located the fountain of life at the base of a great mountain in Ceylon. This “fayr well … hathe odour and savour of all spices; and at every hour of the day, he chaungethe his odour and his savour dyversely. And whoso drinkethe 3 times fasting of that watre of that welle, he is hool (whole) of alle maner (of) sykenesse that he hathe. And they that duellen (dwell) there and drynken often of that welle, thei nevere hau (have) sykenesse, and thei semen (seem) alle weys yonge.” Sir John says that he drank of the water on three or four occasions and fared the better for it. Some men called it the “Welle of Youthe”. They had often drunk from it and seemed “alle weys yongly (youthful)” and lived without sickness. “And men seyn that that welle comethe out of Paradys, and therefore it is so vertuous.” The “tree of life” is always situated near the “well of life” in mediæval literature. At Heliopolis in Egypt a well and tree are connected by Coptic Christians and Mohammedans with Christ. When Joseph and Mary fled to Egypt they rested under this tree, according to Egyptian belief, and the clothes of the holy child were washed in the well. Heliopolis, the Biblical On, is “the city of the sun”, and the Arabs still call the well the “spring of the sun”. According to ancient Egyptian belief the sun-god Ra washed his face in it every morning. The tree, a sycamore, was the mother-goddess.

That European ideas regarding a floating island or islands were of Egyptian origin and closely connected with the solar cult, is suggested by the classical legend regarding Delos, one of the Cyclades. It was fabled to have been raised to the surface of the sea at the command of Poseidon, so that the persecuted goddess Latona, who was pursued from land to land by a python, as the Egyptian Isis was pursued by Set, might give birth there to Apollo. On Delos the image of Apollo was in the shape of a dragon, and delivered oracles. It was unlawful for any person to die on Delos, and those of its inhabitants who fell sick were transported to another island.

Delos was a floating island like the floating island of the Nile, “the green bed of Horus” on which that son of Osiris and Isis hid from Set. The most ancient Apollo was the son of cripple Hephaistos. Cripple Horus was, in one of his forms, a Hephaistos and a metal-worker. Homer knew of the fabled island of Apollo. The swineherd, addressing Odysseus, says,18 “There is a certain isle called Syria … over above Ortygia, and there are the turning places of the sun. It is not very great in compass, though a goodly isle, rich in herds, rich in flocks, with plenty of corn and wine. Dearth never enters the land, and no hateful sickness falls on wretched mortals.”

The later Greeks located the island Paradise in the Atlantic, and it is referred to as “Atlantis”, the Islands of the Blest and the Fortunate Isles (fortunatae insulae). Hercules set out to search for the golden apples, the fruit of immortality that grow in

those Hesperian gardens famed of old,

Fortunate fields and groves and flowery vales.

The garden of Paradise, cared for by those celebrated nymphs, the daughters of Hesperus, brother of Atlas—Hesperus is the planet Venus as an evening star—was also located among the Atlas mountains in Africa. There the tree of life, which bore the golden apples, was guarded by the nymphs and by a sleepless dragon, like the gem-trees in the Paradises of China and Japan.

According to Diodorus, the Phœnicians discovered the island Paradise. Plutarch placed it at a distance of five days’ voyage to the west of Brittia (England and Scotland), apparently confusing it with Ireland (the “sacred isle” of the ancients), or with an island in the Hebrides.

The island of immortals in the western ocean is found in Gaelic folk- and manuscript-literature.

Among the Gaelic names of Paradise is that of “Emain Ablach” (Emain rich in apples). In one description a youth named Conla and his bride Veniusa are referred to. “Now the youth was so that in his hand he held a fragrant apple having the hue of gold; a third part of it he would eat, and still, for all he consumed, never a whit would it be diminished. The fruit it was that supported the pair of them and when once they had partaken of it, nor age nor dimness could affect them.” A part of this Paradise was reserved for “monarchs, kings, and tribal chiefs”. Teigue, a Celtic Gilgamesh who visited the island, saw there “a thickly furnished wide-spreading apple tree that bore blossom and ripe fruit” at the same time. He asked regarding the great tree and was informed that its fruit was “meat” intended to “serve the congregation” which was to inhabit the mansion.19 The rowan berry and hazel nut were also to the Gaels fruits of immortality. There once came to St. Patrick “from the south” a youth wearing a crimson mantle fixed by a fibula of gold over a yellow shirt. He brought “a double armful of round yellow-headed nuts and of beautiful golden-yellow apples”.20 The Gaelic Islands of the Blest are pictured in glowing colours:

Splendours of every colour glisten

Throughout the gentle-voiced plains.

Joy is known, ranked around music

In the southern Silver-cloud Plain.

Unknown is wailing or treachery …

There is nothing rough or hoarse …

Without grief, without sorrow, without death,

Without sickness, without debility …

A lovely land

On which the many blossoms drop.21

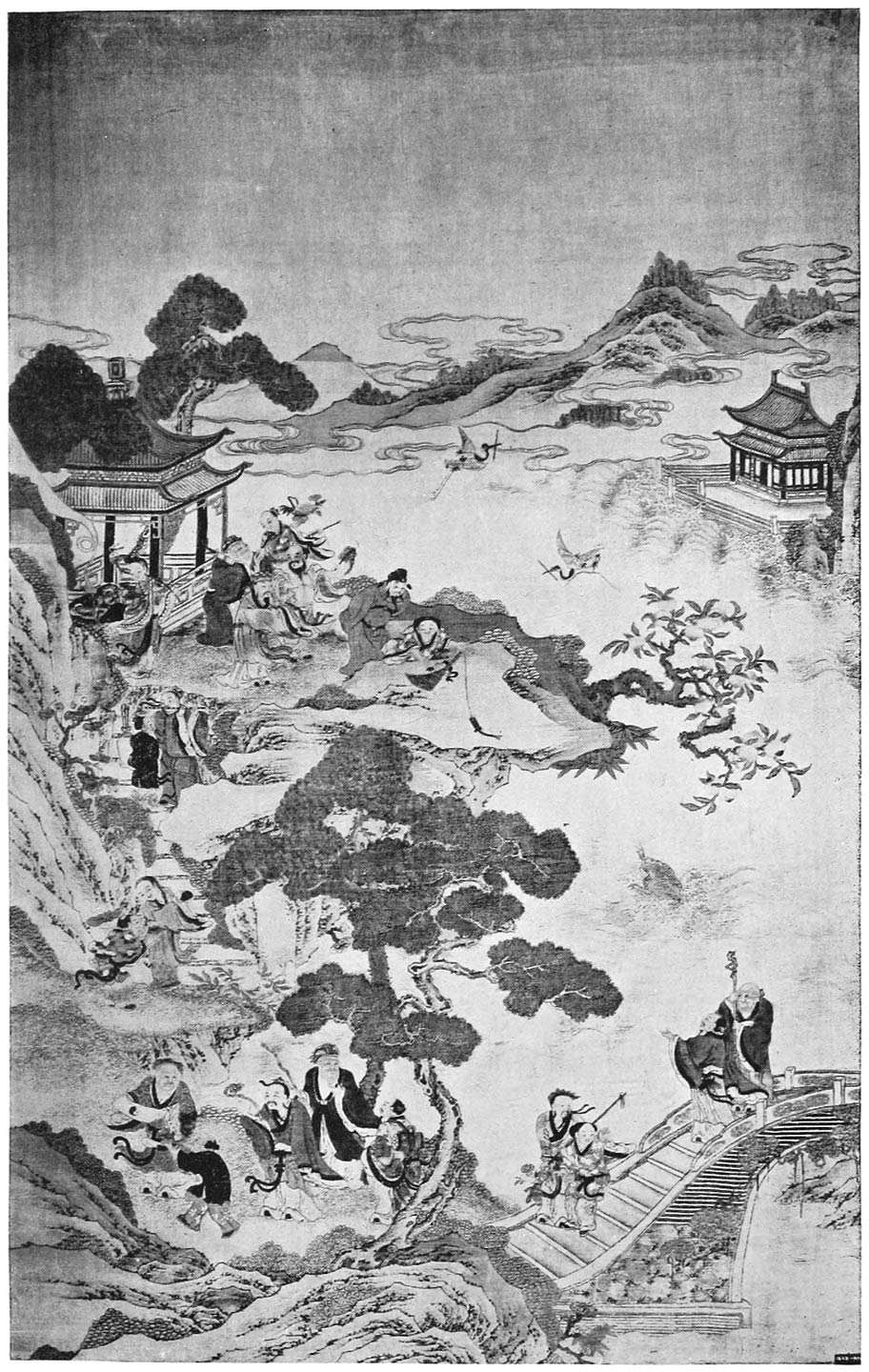

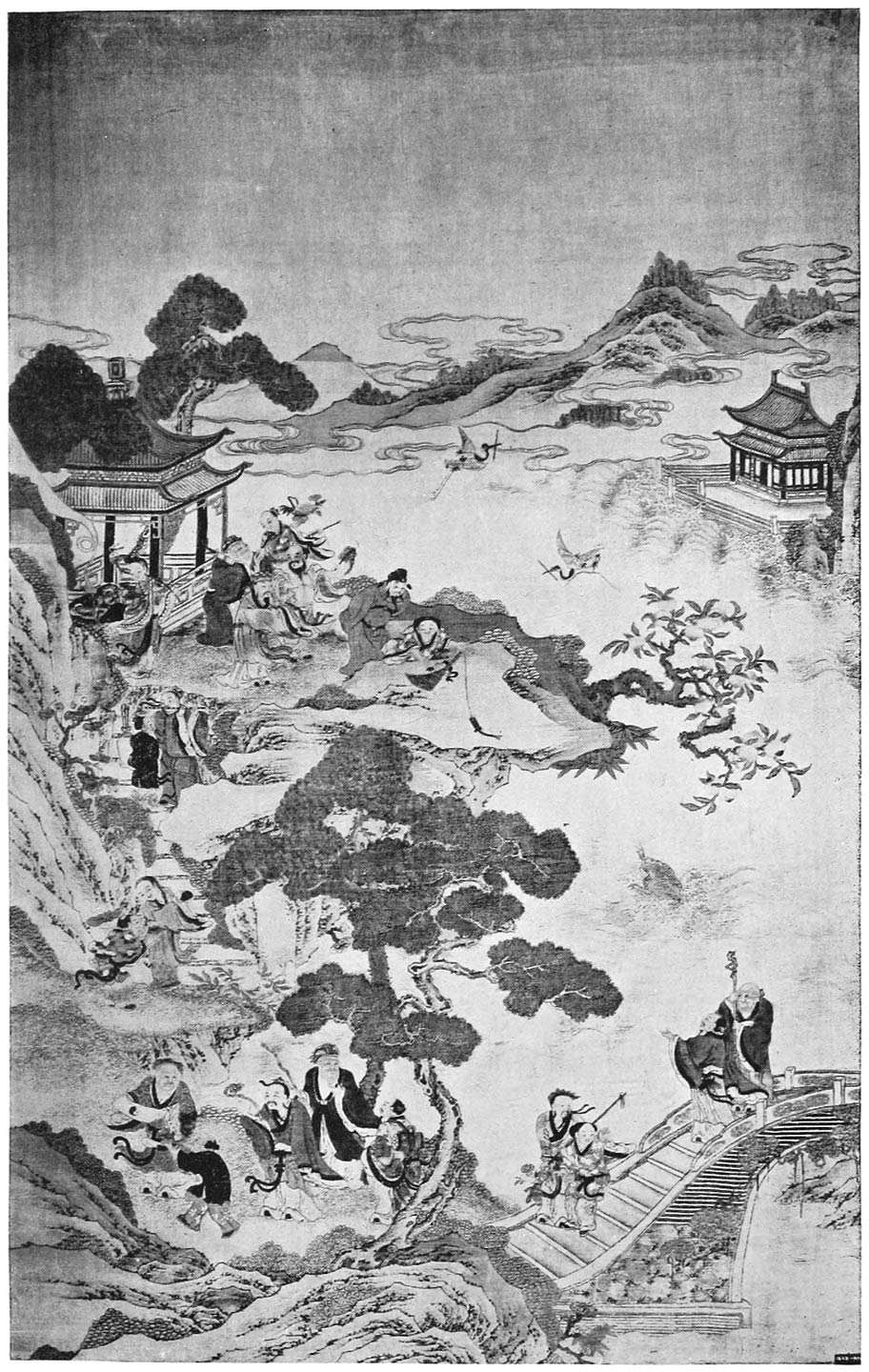

SHOU SHAN (i.e. “HILLS OF LONGEVITY”), THE TAOIST PARADISE

From a woven silk picture in the Victoria and Albert Museum

The hero Bran sets out to search for the islands, and, like one of the Chinese mariners, meets with the sea-god, who addresses him and tells of the wonders of the island Paradise with its trees of life.

A wood laden with beautiful fruit …

A wood without decay, without defect,

On which is a foliage of a golden hue.22

The green floating and vanishing island and the well of life are common in Scottish Gaelic folk-lore. It was believed that the life-giving water had greatest potency if drunk at dawn of the day which was of equal length with the night preceding it, and that it should be drunk before a bird sipped at the well and before a dog barked. The Scandinavians heard of the Gaelic Island of the West during their prolonged sojourn in the British Isles and Ireland, and referred to it as “Ireland hit Mikla” (“The Mickle Ireland”), and the mythical island was afterwards identified with Vinland, believed to be America, which was apparently reached by the hardy sea-rovers.

The Earthly Paradise was also located in Asia. In the mythical histories of Alexander a hero sets forth like Gilgamesh on the quest of the Water of Life. He similarly enters a cavern of a great mountain in the west which is guarded by a monster serpent. In one version of the tale this hero carries a jewel that shines in darkness—a jewel that figures prominently in Chinese lore (Chap. XIII)—and passes through the dark tunnel. He reaches the Well of Life and plunges into it. When he came out he found that his body had turned a bluish-green colour, and ever afterwards he was called “El Khidr”, which means “Green”.23

The Well of Life is referred to in the Koran. Commentators explain a reference to a vanishing fish by telling that Moses or Joshua carried a fried fish when they reached the Well of Life. Some drops of the water fell on the fish, which at once leapt out of the basket into the sea and swam away.

In the Aryo-Indian epic, the Mahábhárata, the hero Bhima sets out in search of the Lake of Life and the Lotus of Life. He overcomes the Yaksha-guardians of the lake, and when he bathes in the lake his wounds are healed.24

There are glowing descriptions in Buddhist literature of the Paradise reached by those who are to qualify for Buddhahood. A proportion of the Chinese Taoist inhabitants of the Islands of the Blest similarly wait for the time when they will pass into another state of existence. A similar belief prevailed in the West. Certain Celtic heroes, like Arthur, Ossian, Fionn (Finn), Brian Boroimhe, and Thomas the Rhymer, live in Paradise for long periods awaiting the time when they are to return to the world of men, as do Charlemagne, Frederick of Barbarossa, William Tell, and others on the Continent.

In the Buddhist Paradise the pure beings have faces “bright and yellowish”, yellow being the sacred colour of the Buddhist as it is the colour of the chief dragon of China. In this Paradise is the Celestial Ganges and the great Bodhi-tree, “a hundred yojanas in height”, which prolongs life and increases “their stock of merit”. Their “merit” may “grow in the following shapes, viz. either in gold, in silver, in jewels, in beryls, in shells, in stones, in corals, in amber, in red pearls, in diamonds, &c., or in any one of the other jewels; or in all kinds of perfumes, in flowers, in garlands, in ointment, in incense-powder, in cloaks, in umbrellas, in flags, in banners, or in lamps; or in all kinds of dancing, singing, and music”.25

The gem-trees abound in this Paradise. “Of some trees”, one account runs, “the trunks are of coral, the branches of red pearls, the small branches of diamonds, the leaves of gold, the flowers of silver, and the fruits of beryl.”26 In the “eastern quarter” there are “Buddha countries equal to the sand of the River Ganga (Ganges)”. The purified beings in the lands “surpass the light of the sun and moon, by the light of wisdom, and by the whiteness, brilliancy, purity, and beauty of their knowledge”.27 There are references to “the king of jewels that fulfils every wish”. It has “golden-coloured rays excessively beautiful, the radiance of which transforms itself into birds possessing the colours of a hundred jewels, which sing out harmonious notes”.28 The purified may become like Buddha “with bodies bright as gold and blue eyes”, for “the eyes of Buddha are like the water of the four great oceans; the blue and the white are quite distinct”.29 The imaginations of the Buddhists run riot in their descriptions of the Land of Bliss, and the stream of glowing narrative carries with it many pre-Buddhist beliefs about metals and precious stones, “red pearls, blue pearls”, and so on, and “nets of gold adorned with the emblems of the dolphin, the svastika (swashtika), the nandyāvarta, and the moon”.30 In their Paradise even the river mud is of gold. The religious ideas of the early searchers for “soul substance” in the form of metals and gems are thus found to be quaintly blended with Buddhist conceptions of the Earthly Paradise.

In some Chinese and Japanese stories the souls of the dead are carried to Paradise by birds, and especially by the crane or stork, which takes the place of the Indian man-eagle Garuda (Japanese Gario, the woman-bird with crane’s legs), and of the Babylonian eagle that carried the hero Etana to heaven. The saints who reach the Indian Paradise of Uttara Kuru, situated at the sources of the River Indus, among the Himalayan mountains, and originally the homeland of the Kuru tribe of Aryans, are supposed to have their lives prolonged for centuries. When they die their bodies are carried away by gigantic birds and dropped into mountain recesses. The belief enshrined in stories of this kind may be traced to the wide-spread legend of the Diamond Valley. Laufer notes that a version of it occurs in the Liang se kung ki, “one of the most curious books of Chinese literature”. A prince is informed by scholars regarding the wonders of distant lands. “In the west, arriving at the Mediterranean,” one Chinese story runs, “there is in the sea an island of two hundred square miles. On this island is a large forest, abundant in trees with precious stones, and inhabited by over ten thousand families. These men show great ability in cleverly working gems, which are named for the country Fu-lin (Syria). In a north-westerly direction from the island is a ravine, hollowed out like a bowl, more than a thousand feet deep. They throw flesh into this valley. Birds take it up in their beaks, whereupon they drop the precious stones.” Here Fu-lin, in the Mediterranean area, is referred to as early as the beginning of the sixth century.

The Chinese Diamond Valley story is “an abridged form of a well-known Western legend”. In a version of it in the writings of Epiphanius, Bishop of Constantia in Cyprus (c. 315–403), the valley is situated in “a desert of great Scythia”, and the precious stones are gathered on the mountains, whence the eagles carry them. The eagle-stone is “useful to women in aiding parturition”. Laufer notes that Pliny knew about the parturition stone, and that the beliefs associated with it are found in Egypt and India. In the latter country it occurs in legends about the combats between the eagle and serpent.31

A Scottish Gaelic folk-story tells of a man who had a combat with an eagle which carried him away to the floating island of the blest. He was killed, but came to life again after drops of the water from the well of life were thrown on his body. Stones found in eagles’ or ravens’ nests, according to Scottish belief, imparted to their possessors the power of prophecy or healing.

The gems from the trees of Paradise in Babylonian, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese literature were supposed to confer special powers on those who became possessed of them. To this class belongs the “Jewel that grants all Desires”, the “gem that shines in darkness”, the prophet’s or priest’s jewel or jewels, &c. Gems were searched for in ancient times because they were supposed to possess what has been called “soul substance”. They protected those who wore them from all evil, they assisted birth, they prolonged life. Precious metals were similarly believed to be “luck-bringers”, and to early man luck meant everything he wished for, including good health, longevity, plentiful supplies of food, a knowledge of the future, offspring, and so on.

In the stories of the Islands of the Blest the happy souls are, in the ancient sense of the term, “lucky souls”. Paradise was a land in which life-giving water and fruit, and innumerable gems were to be found, and those who reached it became wise as magicians and prophets, and lived for thousands of years free from sickness and pain. It was the land of eternal youth and unlimited happiness.