CHAPTER X

THE MOTHER-GODDESS OF CHINA AND JAPAN

Food for the Dead—Milk, Bread, and Beer in Paradise—The Western Tree of Life in Egypt—Tree of Life in Greece, Britain, and Polynesia—The Underworld Paradise—The “Wonderful Rose Garden”—Chinese Cult of the West—Biblical Tree Parable—Chinese Peach Tree of Longevity—The “Royal Mother of the West”—Visit of the Chinese Emperor—A Far-Eastern El-Khidr—The Sacred Chrysanthemum—The Cassia Tree Cult—Celestial Yellow River—Moon Myths—Lunar Elixir in China, India, and Scandinavia—Chinese Star Maiden—The Sun Barque—“Island of Blest” in Celestial River—Moon-girl Story—The “Makara” in China and Japan—The Chinese Ishtar—Deluge Legend—Tree Spirits—Story of Little Peachling—“Soul Substance” in Dragon Bones, Trees, and Pearls.

The quest of the “elixir of life”, the “water of life”, or “the food of life” is as prominent a feature of ancient religious literature as is the quest of the Holy Grail in the Arthurian romances. As has been shown in the last chapter, the belief that prompted the quest was widely prevalent, and of great antiquity. The Babylonian hero, Gilgamesh, whose story is told in the oldest epic in the world, undertook his long and perilous journey to the Otherworld, in quest of the Plant of Life, because the thought of death was sorrowful to him. When his friend, Ea-bani, had expired,

Gilgamesh wept bitterly, and he lay stretched out upon the ground.

He cried, “Let me not die like Ea-bani.…

I fear death.”1

In the Babylonian myth of Adapa reference is made to the “water of life” and the “food of life”, which give wisdom and immortality to the gods and to the souls of those mortals who win their favour. The sacred tree in Babylonian art is evidently the Tree of Life.2

We seem to meet with the history of the immemorial quest in the Pyramid Texts of Ancient Egypt. The ancient priests appear to have concerned themselves greatly regarding the problem how the dead were to be nourished in the celestial Paradise. “The chief dread felt by the Egyptian for the hereafter,” says Breasted, “was fear of hunger.”3 In Egypt, as in other lands offerings of food were made at the tombs, and these were supposed to be conveyed to the souls by certain of the gods. But those who hoped to live for ever knew well that the time would come when grave-offerings would cease to be made, and their own names would be forgotten on earth. Some Pharaohs endowed their chapel-tombs for all time, but revolutions ultimately caused endowments to be appropriated.

The Babylonians believed that if the dead were not fed, their ghosts would prowl through the streets and enter houses, searching for food and water.4 In Polynesia the homeless and desolate ghosts were those of poor people, “who during their residence in the body had no friends and no property”.5 The custom of including food-vessels and drinking-cups in the funerary furniture of prehistoric graves in different countries was no doubt connected with the fear of hunger in the hereafter. The custom was widespread of giving the dead food offerings at regular intervals. Once a year the living held feasts in the burial-grounds, and invited the dead to partake of their share. Among the Hallowe’en beliefs in the British Isles is one that ghosts return home during the year-end festival to attend “the feast of all souls”. The Hebridean custom, which lingered even in the nineteenth century, of placing food and water, or milk, beside a corpse while it lay in a house, and outside the door or at the grave after the burial took place, was no doubt a relic of an ancient custom, based on the haunting belief that the dead were in need of nourishment, if not for all time, at any rate until the journey to the Otherworld was completed.

As has been said, it was the provision of food in the celestial Paradise, far removed from the earth and its produce, that chiefly concerned the Egyptians. In the Underworld Kingdom, presided over by Osiris, the souls grew corn and gathered fruit. But the Paradise of the solar cult was above or beyond the sky. Some of the sun-worshippers are found in the Pyramid Texts to have placed their faith in the food-supplying Great Mother, the goddess Hathor, who gave them corn and milk during their earthly lives. As son of Re, born of the sky-goddess, he (the Pharaoh) is frequently represented as suckled by one of the sky-goddesses, or some other divinity connected with Re, especially the ancient goddesses of the prehistoric kingdoms of South and North. These appear as “the two vultures with long hair and hanging breasts; … they draw their breasts over the mouth of King Pepi, but they do not wean him forever.…” Another text invokes the mother-goddess: “Give thy breast to this King Pepi, … suckle this King Pepi therewith”. As a result, perhaps, of the prevalence of Osirian beliefs, the solar cult adopted the idea that food, such as is found in Egypt, might be provided in the regions above or beyond the sky. The sun-god was appealed to: “Give thou bread to this King Pepi, from this thy eternal bread, thy everlasting beer”.6

But the chief source of nourishment in the celestial Paradise was the Tree of Life (a form of the mother-goddess) on the great isle in the mythical lake or sea beyond the Eastern horizon.7 Egyptian artists depicted this tree as a palm, or sycamore, with a goddess rising from inside it, pouring water from a vessel on the hands of the Pharaoh’s soul, which might appear in human form, or in the man-bird form called the ba. In the funeral ritual the ceremony of pouring out a libation was performed with the object of restoring the body moisture (the water of life) to the mummy.8 A Biblical reference to the ceremony is found in 2 Kings, iii, 11, in which it is said of Elisha that he “poured water on the hands of Elijah”. No doubt the Egyptian soul received water as nourishment, as well as to ensure its immortality, from the tree-goddess.

In the Book of the Dead (Chapter LIX), the Tree of Life is referred to as “the sycamore of Nut” (the sky-goddess). Other texts call the tree “the Western Tree” of Nut or Hathor. It may be that the solar cult of the East took over the tree from the Osirian cult of the West.

This mythical tree figures in many ancient mythologies. The goddess Europa was worshipped at Gortyna, in Crete, during the Hellenic period, as a sacred tree.9 The tree may be traced from the British Isles to India, and there are numerous legends of spirits entering or leaving it. The Polynesians have stories of this kind. Their Tree of Life was the local bread-fruit tree which “became a god”, or, as some had it, a goddess. “Out of this magic bread-fruit tree,” a legend says, “a great goddess was made.”10

It may be that the island Paradise with its Tree of Life was specially favoured after maritime enterprise made strong appeal to the imagination of the Egyptians. No doubt the old sailors who searched for “soul-substance” in the shape of pearls, precious stones, and metals had much to do with disseminating the idea of the Isles of the Blest. At any rate, it became, as we have seen, a tradition among seafarers to search for the distant land in which was situated the “water of life”. The home-dwelling Osirians clung to their idea of an Underworld Paradise, and belief in it became fused with that of the floating island, or Islands of the Blest. Those who dwelt in inland plains and valleys, and those accustomed to cross the great mysterious deserts on which the oasis-mirage frequently appeared and vanished like the mythical floating island, conceived of a Paradise on earth. There are references in more than one land to a Paradise among the mountains. It figures in the fairy stories of Central Europe, for instance, as “the wonderful Rose Garden” with its linden Tree of Immortality, the hiding-place of a fairy lady, its dancing nymphs and its dwarfs; the king of dwarfs has a cloak of invisibility which he wraps round those mortals he carries away.11

At first only the souls of kings entered Paradise. But, in time, the belief became firmly established that the souls of others could reach it too, and be fed there. The quest of the “food of life” then became a popular theme of the story-tellers, and so familiar grew the idea of the existence of this fruit that people believed it could be obtained during life, and that those who partook of it might have their days prolonged indefinitely. For, as W. Schooling has written, “a few simple thoughts on a few simple subjects produce a few simple opinions common to a whole tribe” (and even a great part of mankind), “and are taught with but little modification to successive generations; hence arises a rigidity that imposes ready-made opinions, which are seldom questioned, while such questioning as does occur is usually met with excessive severity, as Galileo and others have found out”.12

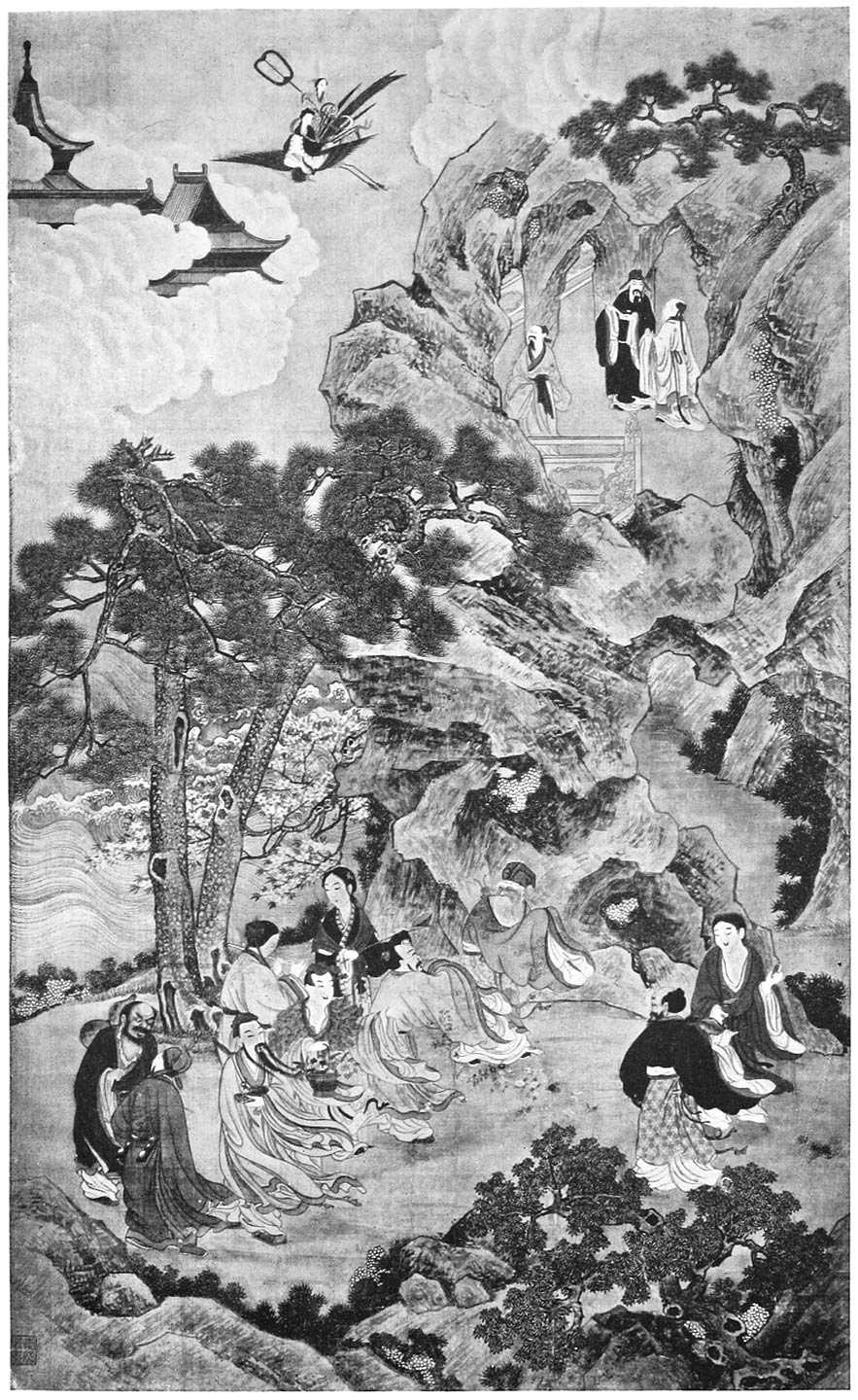

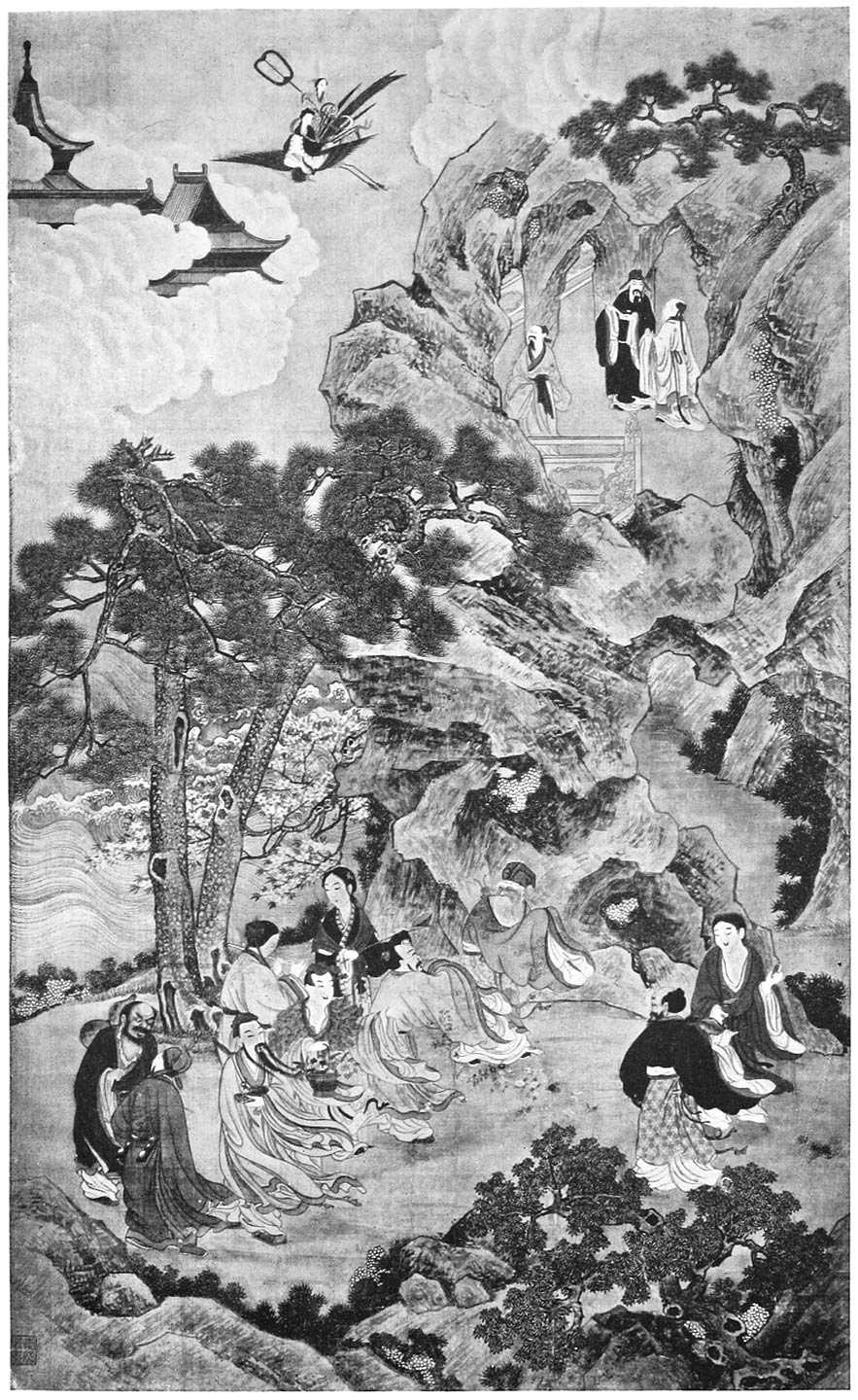

THE CHINESE SI WANG MU (JAPANESE SEIOBO) AND MAO NU

From a Japanese painting (by Hidenobu) in the British Museum

The apple, as we have seen, was to the Celts the fruit of immortality: the Chinese favoured the peach—that is, it was favoured by the Chinese cult of the West. As all animals were supposed to be represented in the Otherworld by gigantic prototypes—the fathers or mothers of their kind—so were trees represented by a gigantic tree.13 This tree was the World Tree that supported the Universe. In Egypt the World Tree was the sycamore of the sky-goddess, who was the Great Mother of deities and mankind. The sun dropped into the sycamore at eventide; when darkness fell the swallows (star-gods) perched in its branches. In Norse mythology the tree is the ash, called Ygdrasil, and from the well at its roots souls receive the Hades-drink of immortality, drinking from a horn embellished with serpent symbols. The Tree figures prominently in Iranian mythology: the Aryo-Indian Indra constructs the World-house round it. This Tree is, no doubt, identical with the sacred tree in Assyrian art, which is sometimes the date, the vine, the pomegranate, the fir, the cedar, and perhaps the oak. It may be that the Biblical parable about the talking trees is a memory of the rivalries of the various Assyrian tree cults:

The trees went forth on a time to anoint a king over them; and they said unto the olive tree, Reign thou over us. But the olive tree said unto them, Should I leave my fatness, wherewith by me they honour god and man, and go to be promoted over the trees? And the trees said to the fig tree, Come thou, and reign over us. But the fig tree said unto them, Should I forsake my sweetness, and my good fruit, and go to be promoted over the trees? Then said the trees unto the vine, Come thou, and reign over us. And the vine said unto them, Should I leave my vine, which cheereth God and man, and go to be promoted over the trees? Then said all the trees unto the bramble, Come thou, and reign over us. And the bramble said unto the trees, If in truth ye anoint me King over you, then come and put your trust in my shadow: and if not, let fire come out of the bramble, and devour the cedars of Lebanon.

As in Assyria, there was in China quite a selection of life-giving trees.

The Chinese gigantic Peach Tree, whose fruit was partaken of by gods and men, grew in the Paradise among the Kwun-lun mountains in Tibet, and, like the Indian Mount Meru (“world spine”), supported the Universe. Its fruit took three thousand years to ripen. The tree was surrounded by a beautiful garden, and was under the care of the fairy-like lady Si Wang Mu, the queen of immortals, the “Mother of the Western King”, and the “Royal Mother of the West”. She appears to have originally been the mother-goddess—the Far-Eastern form of Hathor. In Japan she is called Seiobo. Her Paradise, which is called “the palace of exalted purity”, and “the metropolis of the pearl mountain”, or of “the jade mountain”, and is entered through “the golden door”,14 was originally that of the cult of the West. Sometimes Si Wang Mu is depicted as quite as weird a deity as the Phigalian Demeter, with disordered hair, tiger’s teeth, and a panther’s tail. Her voice is harsh, and she sends and cures diseases. Three blue birds bring food to her.

Chinese emperors and magicians were as anxious to obtain a peach from the Royal Mother’s tree in the Western Paradise, as they were to import the “fungus of immortality” from the Islands of the Blest in the Eastern Sea.

There once lived in China a magician named Tung Fang So, who figures in Japanese legend as Tobosaku, and is represented in Japanese art as a jolly old man, clasping a peach to his breast and performing a dance, or as a dreamy sage, carrying two or three peaches, and accompanied by a deer—an animal which symbolized longevity. Various legends have gathered round his name. One is that he had several successive rebirths in various reigns, and that originally he was an avatar of the planet Venus. He may therefore represent the Far-Eastern Tammuz, the son of the mother-goddess. Another legend tells that he filched three peaches from the Tree of Life, which had been plucked by the “Royal Mother of the West”.

Tung Fang So was a councillor in the court of Wu Ti, the fourth emperor of the Han Dynasty, who reigned for over half a century, and died after fasting for seven days in 87 B.C. In Japanese stories Wu Ti is called Kan no Buti. He was greatly concerned about finding the “water of life” or the “fruit of life”, so that his days might be prolonged. In his palace garden he caused to be erected a tower over 100 feet high, which appears to have been an imitation of a Babylonian temple. On its summit was the bronze image of a god, holding a golden vase in its hands. In this vase was collected the pure dew that was supposed to drip from the stars. The emperor drank the dew, believing that it would renew his youth.

One day there appeared before Wu Ti in the palace garden a beautiful green sparrow. In China and Japan the sparrow is a symbol of gentleness, and a sparrow of uncommon colour is supposed to indicate that something unusual is to happen. The emperor was puzzled regarding the bird-omen, and consulted Tung Fang So, who informed him that the Queen of Immortals was about to visit the royal palace.

Before long Si Wang Mu made her appearance. She had come all the way from her garden among the Kwun-lun mountains, riding on the back of a white dragon, with seven of the peaches of immortality, which were carried on a tray by a dwarf servant. Her fairy majesty was gorgeously attired in white and gold, and spoke with a voice of bird-like sweetness.

When she reached Wu Ti there were only four peaches on the tray, and she lifted one up and began to eat it. The peach was her symbol, as the apple was that of Aphrodite. Tung Fang So peered at her through a window, and when she caught sight of his smiling face, she informed the emperor that he had stolen three of her peaches. Wu Ti received a peach from her, and, having eaten it, became an immortal. A similar story is told regarding the Chinese Emperor, Muh Wang.

In her “Jade Mountain” Paradise of the West (the highest peak of the Kwun-lun mountains) this goddess is accompanied by her sister, as the Egyptian Isis is by Nephthys, and the pair are supposed to flit about in Cloud-land, followed by the white souls of good women of the Taoist cult. Her attendants include the Blue Stork, the White Tiger, the Stag, and the gigantic Tortoise, which are all gods and symbols of longevity in China.

Among the many stories told about Tung Fang So is one regarding a visit he once paid to the mythical Purple Sea. He returned after the absence of a year, and on being remonstrated with by his brother for deserting his home for so long a period, he contended that he had been away for only a single day. His garments had been discoloured by the waters of the Purple Sea, and he had gone to another sea to cleanse them. In like manner heroes who visit Fairyland find that time slips past very quickly.

The Purple Sea idea may have been derived from the ancient Well of Life story about El Khidr,15 whose body and clothing turned green after he had bathed in it. Purple supplanted green and blue as the colour of immortality and royalty after murex dye became the great commercial asset of sea-traders. Tung Fang So may have had attached to his memory a late and imported version of the El Khidr story.

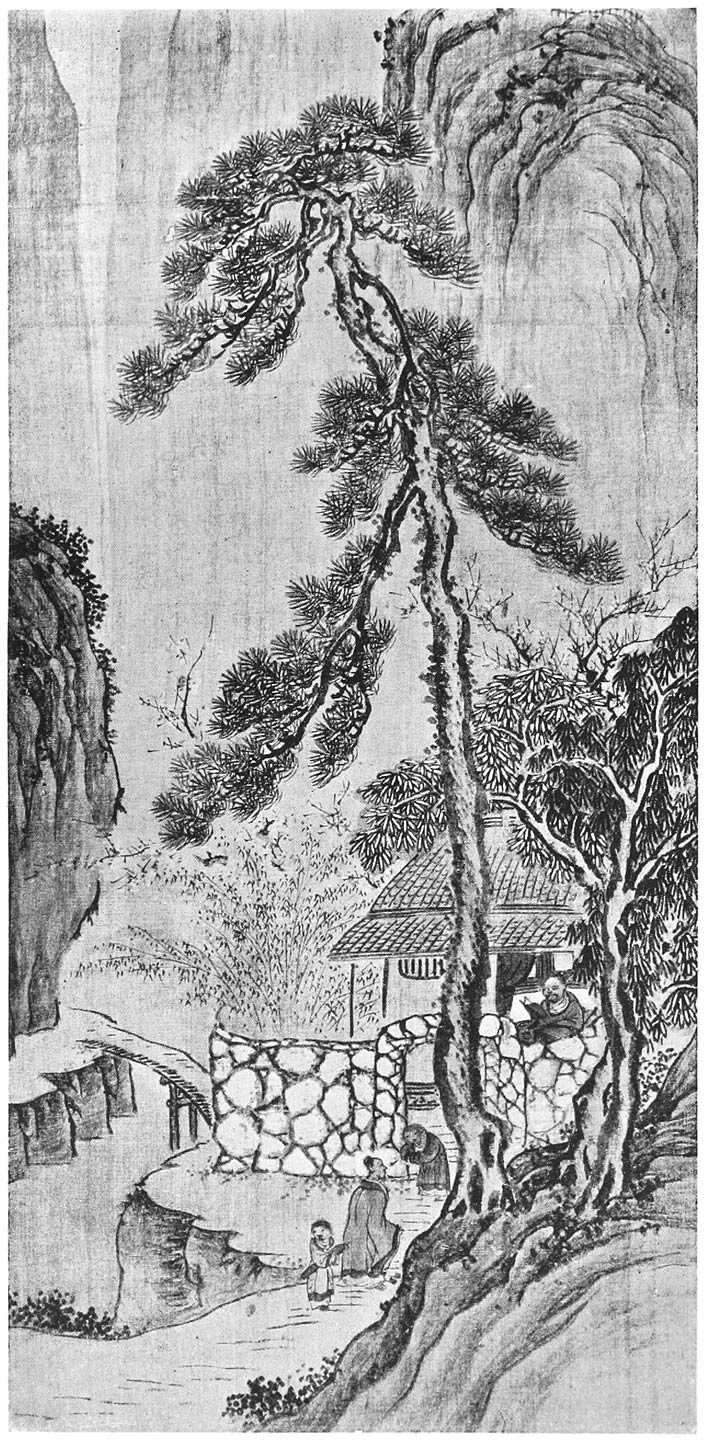

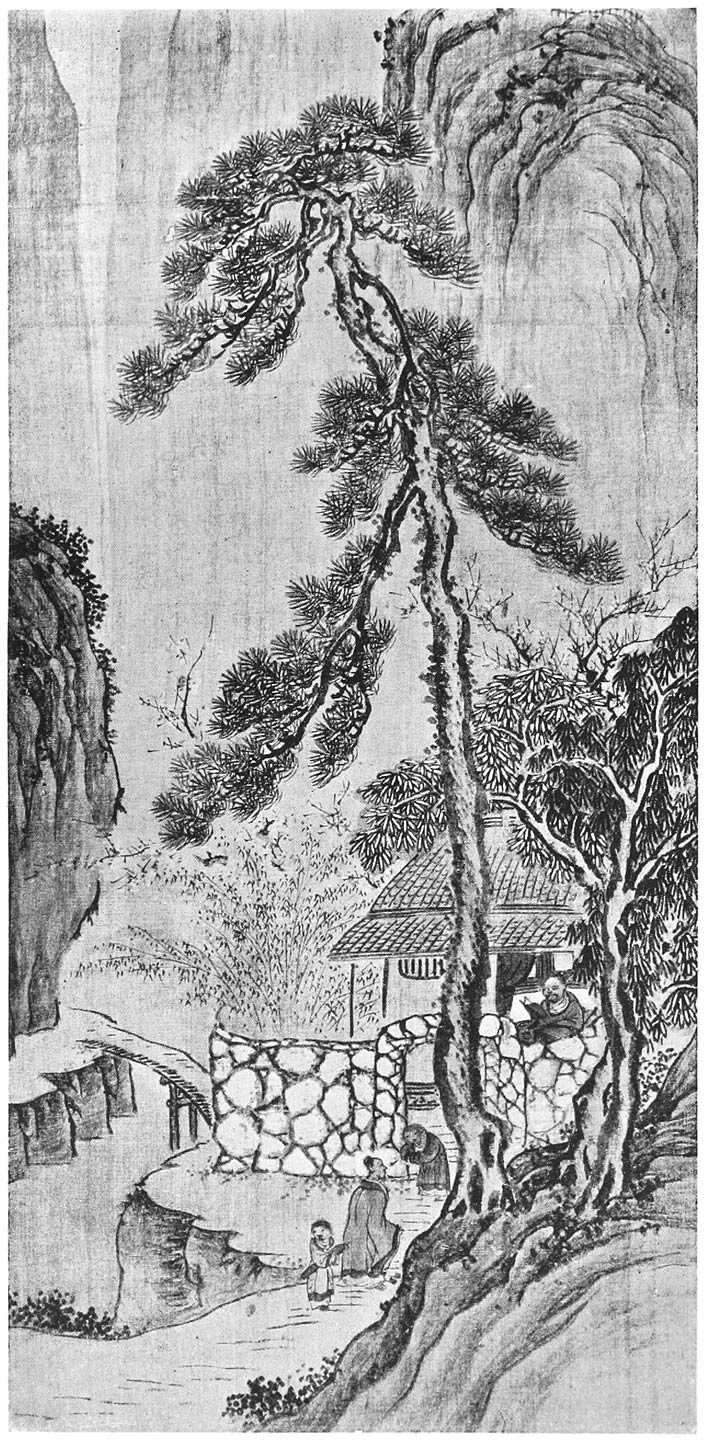

MOUNTAIN VIEW WITH SCHOLAR’S RETREAT

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

The reference to Wu Ti’s dew-drinking habit recalls the story of the youthful Keu Tze Tung, a court favourite, who unwittingly offended the emperor, Muh Wang, and was banished. As the Egyptian Bata, who similarly fell into disgrace in consequence of a false charge being made against him, fled to the “Valley of the Acacia”, Keu Tze Tung fled to the “Valley of the Chrysanthemum”. There he drank the dew that dropped from the petals of chrysanthemums, and became an immortal. The Buddhists took over this story, and told that the youth had been given a sacred text, which he painted on the petals. This text imparted to the dew its special qualities. In the Far East the chrysanthemum is a symbol of purity. The chrysanthemum with sixteen petals is the emblem of the Mikado of Japan.

A Chinese sage, who, like the Indian Rishis, practised yoga until he became immortal, engaged his spare moments in painting fish. He lived on the bank of a stream for over two hundred years. In the end he was carried away to the Underworld Paradise of the Lord of Fish, who was, of course, the dragon-god. He paid one return visit to his disciples, riding like the Chinese “Boy Blue” in the dragon story, on the back of a red carp.

Another Chinese “tree-cult” favoured, instead of the peach tree, a cassia tree. This cassia-cult must have been late. The peach tree is indigenous. “Of fruits,” says Laufer, “the West is chiefly indebted to China for the peach (Amygdalus persica) and the apricot (Prunus armeniaca). It is not impossible that these two gifts were transmitted by the silk-dealers, first to Iran (in the second or first century B.C.) and thence to Armenia, Greece, and Rome (in the first century A.D.).” In India the peach is called cinani (“Chinese fruit”). “There is no Sanskrit name for the tree (peach); nor does it play any rôle in the folk-lore of India, as it does in China.” … Persia “has only descriptive names for these fruits, the peach being termed saft alu (‘large plum’), the apricot, zard alu (‘yellow plum’).”16

It is difficult to identify the cassia tree of Chinese religious literature. “The Chinese word Kwei occurs at an early date, but it is a generic term for Lauraceæ; and there are about thirteen species of Cassia, and about sixteen species of Cinnamomum in China. The essential point is that the ancient texts maintain silence as to cinnamon; that is, the product from the bark of the tree. Cinnamomum cassia is a native of Kwan-si, Kwan-tun, and Indo-China; and the Chinese made its first acquaintance under the Han, when they began to colonize and to absorb southern China.” The first description of this tree goes no farther back than the third century. “It was not the Chinese, but non-Chinese peoples of Indo-China who first brought the tree into civilization, which, like all other southern cultivations, was simply adopted by the conquering Chinese.”17 It has been suggested that the cinnamon bark was imported into Egypt from China as far back as the Empire period (c. 1500 B.C.) by Phœnician sea-traders.18 Laufer rejects this theory.19 Apparently the ancient Egyptians imported a fragrant bark from their Punt (Somaliland, or British East Africa). At a very much later period cinnamon bark was carried across the Indian Ocean from Ceylon.

The Egyptians imported incense-bearing trees from Punt to restore the “odours of the body” of the dead, and poured out libations to restore its lost moisture.20 “When”, writes Professor Elliot Smith, “the belief became well established that the burning of incense was potent as an animating force, and especially a giver of life to the dead, it naturally came to be regarded as a divine substance in the sense that it had the power of resurrection. As the grains of incense consisted of the exudation of trees, or, as the ancient texts express it, ‘their sweat’, the divine power of animation in course of time became transferred to trees. They were no longer merely the source of the life-giving incense, but were themselves animated by the deity, whose drops of sweat were the means of conveying life to the mummy.… The sap of trees was brought into relationship with life-giving water.… The sap was also regarded as the blood of trees and the incense that exuded as sweat.” As De Groot reminds us, “tales of trees that shed blood, and that cry out when hurt are common in Chinese literature (as also in Southern Arabia, notes Elliot Smith); also of trees that lodge, or can change into maidens of transcendent beauty.”21

Apparently the ancient seafarers who searched for incense-bearing trees carried their beliefs to distant countries. The goddess-tree of the peach cult was evidently the earliest in China. It bore the fruit of life. The influence that led to the foundation of this cult probably came by an overland route. The cassia-tree cult was later, and beliefs connected with it came from Southern China; these, too, bear the imprint of ideas that were well developed before they reached China.

There are references in Chinese lore to a gigantic cassia tree which was 10,000 feet high. Those who ate of its fruit became immortal. The earlier belief connected with the peach tree was that the soul who ate one of its peaches lived for 3000 years.

This cassia world-tree appears first to have taken the place of the peach tree of the “Royal Mother of the West”. It was reached by sailing up the holiest river in China, the Hoang-Ho (Yellow River), the sources of which are in the Koko-Nor territory to the north of Tibet. It wriggles like a serpent between mountain barriers before it flows northward; then it flows southward for 200 miles on the eastern border of Shensi province (the Chinese homeland), and then eastward for 200 miles, afterwards diverging in a north-easterly direction towards the Gulf of Chihli, in which the Islands of the Blest were supposed to be situated.

It was believed that the Hoang-Ho had, like the Ganges of India and the Nile of Egypt, a celestial origin. Those sages who desired to obtain a glimpse of Paradise sailed up the river to its fountain head. Some reached the tree and the garden of Paradise. Others found themselves sailing across the heavens. The Western Paradise was evidently supposed by some to be situated in the middle of the world, and by others to have been situated beyond the horizon.

Chang Kiʼen, one of the famous men attached to the court of Wu Ti, the reviver of many ancient beliefs and myths, was credited with having followed the course of the sacred river until he reached the spot where the cassia tree grew. Beside the tree were the immortal animals that haunt the garden of the “Royal Mother of the West”. In addition, Chang Kiʼen saw the moon-rabbit or moon-hare, which is adored as a rice-giver. In the Far East, as in the Near East and in the West, the moon is supposed to ripen crops. The lunar rabbit or hare is associated with water; in the moon grow plants and a tree of immortality. There is also, according to Chinese belief, a frog in the moon. It was originally a woman, the wife of a renowned archer, who rescued the moon from imprisonment in masses of black rain-clouds. The “Royal Mother of the West” was so grateful to the archer for the service he had rendered that she gave him a jade cup filled with the dew of immortality. His wife stole the cup and drank the dew. For this offence the “Royal Mother of the West” transformed her into a frog, and imprisoned her in the moon. In Egypt the frog was a symbol of resurrection or rebirth, and the old frog-goddess Hekt is usually regarded as a form of Hathor, the Great Mother.

The lunar tree is sometimes identified with the cassia tree of immortality. Its leaves are red as blood, and the bodies of those who eat of its fruit become as transparent as still water.

The moon-water which nourishes plants and trees (eight lunar trees of immortality are referred to in some legends), and the dew of immortality in the jade cup, appear to be identical with the Indian soma and the nectar of the classical gods. In Norse mythology the lunar water-pot (a symbol of the mother-goddess) was filled at a well by two children, the boy Hyuki and the girl Bil,22 who were carried away by the moon-god Mani. Odin was also credited with having recovered the moon-mead from the hall of Suttung, “the mead wolf”, after it had been stolen from the moon. The god flew heavenward, carrying the mead, in the form of an eagle.23 Zeus’s eagle is similarly a nectar-bringer.

In Indian mythology the soma was contained in a bowl fashioned by Twashtri, the divine artisan, and was drunk by the gods, and especially by Indra, the rain-bringer. A Vedic frog-hymn was chanted by Aryo-Indian priests as a rain-charm when Indra’s services were requisitioned. In one of the Indian legends an eagle or falcon carries the soma to Indra. The souls who reach Paradise are made immortal after they drink of the soma. In India the soma was personified, and the lunar god, Soma, became a god of love, immortality, and fertility. The soma juice was obtained by the Vedic priests from some unknown plant. There are also references in Indian mythology to the “Amrita”, which was partaken of by the gods. It was the sap of sacred trees that grew in Paradise. Trees and plants derived their life and sustenance from water. The Far-Eastern beliefs in “the dew of immortality”, “the fungus of immortality”, and “the fruit of immortality” have an intimate connection with the belief that the mother-goddess was connected with the moon, which exercised an influence over water. The mother-goddess was also the love-goddess, the Ishtar of Babylonia, the Hathor of Egypt, the Aphrodite of Greece. Her son, or husband, was, in one of his phases, the love-god.

The sage of the Chinese Emperor Wu Ti, who followed the course of the Yellow River so as to reach the celestial Paradise, saw, in addition to the moon-rabbit, or hare, the “Old Man of the Moon”, the Chinese Wu Kang and Japanese Gekkawo, the god of love and marriage. He is supposed to unite lovers by binding their feet with invisible red silk cords. The “Old Man in the Moon” is, in Chinese legend, engaged in chopping branches from the cassia tree of immortality. New branches immediately sprout forth to replace those thus removed, but the “Old Man” has to go on cutting till the end of time, having committed a sin for which his increasing labour is the appropriate punishment.

A Buddhist legend makes Indra the old man. He asked for food from the hare, the ape, and the fox. The hare lit a fire and leapt into it so that the god might be fed. Indra was so much impressed by this supreme act of friendship and charity that he placed the exemplary hare in the moon. A version of this story is given in the Mahábhárata.

In European folk-lore the “Old Man” is either a thief who stole a bundle of faggots, or a man who “broke the Sabbath” by cutting sticks on that holy day.

See the rustic in the Moon,

How his bundle weighs him down;

Thus his sticks the truth reveal

It never profits man to steal.

Various versions of the Man in the Moon myth are given by S. Baring-Gould,24 who draws attention to a curious seal “appended to a deed preserved in the Record office, dated the 9th year of Edward the Third (1335)”. It shows the “Man in the Moon” carrying his sticks and accompanied by his dog. Two stars are added. The inscription on the seal is, “Te Waltere docebo cur spinas phebo gero (I will teach thee, Walter, why I carry thorns in the moon)”. The deed is one of conveyance of property from a man whose Christian name was Walter.

Wu Ti’s sage travelled through the celestial regions until he reached the Milky Way, the source of the Yellow River. He saw the Spinning Maiden, whose radiant garment is adorned with silver stars. She had a lover, from whom she was separated, but once a year she was allowed to visit him, and passed across the heavens as a meteor. This Spinning Maiden, who weaves the net of the constellations, is reminiscent of the Egyptian sky-goddess, Hathor (or Nut), whose body is covered with stars, and whose legs and arms, as she bends over the earth, “represent the four pillars on which the sky was supposed to rest and mark the four cardinal points”. Her lover, from whom she was separated, was Seb.25 In China certain groups of stars are referred to as the “Celestial Door”, the “Hall of Heaven”, &c. Taoist saints dwell in stellar abodes, as well as on the “Islands of the Blest”; some were, during their life on earth, incarnations of star-gods. The lower ranks of the western-cult immortals remain in the garden of the “Royal Mother”; those of the highest rank ascend to the stars.

Wu Ti’s sage, according to one form of the legend, never returned to earth. His boat, which sailed up the Yellow River and then along the “Milky Way”, was believed to have reached the Celestial River that flows round the Universe, and along which sails the sun-barque of the Egyptian god Ra (or Re). One day the Chinese sage’s oar—apparently his steering oar—was deposited in the Royal Palace grounds by a celestial spirit, who descended from the sky. Here we have, perhaps, a faint memory of the visits paid to earth from the celestial barque by the Egyptian god Thoth, in his captivity as envoy of the sun-god Ra.

There is evidence in Far-Eastern folk-tales that at a very remote period the beliefs of the cult of the sky-goddess, which placed the tree of immortality in the “moon island”, and the beliefs of the peach cult of “the Westerners” were fused, as were those of the Osirian and solar cults in Egypt.

A curious story tells that once upon a time a man went to fish on the Yellow River. A storm arose, and his boat was driven into a tributary, the banks of which were fringed with innumerable peach trees in full blossom. He reached an island, on which he landed. There he was kindly treated by the inhabitants, who told that they had fled from China because of the oppression of the emperor. This surprised the fisherman greatly. He asked for particulars, and was given the name of an emperor who had died about 500 years before he himself was born.

“What is the name of this island?” he asked. The inhabitants were unable to tell him. “We came hither,” they said, “just as you have come. We are strangers in a strange land.”

Next day the wanderer launched his boat and set out to return by the way he had come. He sailed on all day and all night, and when morning came he found himself amidst familiar landmarks. He was able to return home.

When the fisherman told the story to a priest, he was informed that he had reached the land of the Celestials, and that the river fringed by peach trees in blossom was the Milky Way.

In this story the Chinese Island of the Blest is, like the Nilotic “green bed of Horus”, a river island.

Another memory of the Celestial River and the Barque of the Sun is enshrined in the story of Lo Tze Fang, a holy woman of China who ascended to heaven by climbing a high tree—apparently the “world-tree”. After reaching the celestial regions she was carried along the Celestial River in a boat. According to the story, she still sails each day across the heavens.

Other saintly people have been carried to the celestial regions by dragons. According to Chinese belief the “Yellow Dragon” is connected with the moon. The reflection of the moon on rippling water is usually referred to as the “Golden Dragon”, or “Yellow Dragon”, the chief of Chinese dragons, and usually associated with the sun.

One of the classes of Chinese holy men of the Spirit-world, the Sien Nung, who bear a close resemblance to Indian Rishis, is connected with the moon cult. They are believed to prolong their lives by eating the leaves of the lunar plants.

In an Egyptian legend it is told that Osiris was the son of the Mother Cow, who had conceived him when a fertilizing ray of light fell from the moon. In like manner a moon-girl came into being in Japan. She was discovered by a wood-cutter. One day, when collecting bamboo, he found inside a cane a little baby, whose body shone as does a gem in darkness. He took her home to his wife, and she grew up to be a very beautiful girl. She was called “Moon Ray”, and after living for a time on the earth returned to the moon. She had maintained her youthful appearance by drinking, from a small vessel she possessed, the fluid of immortality.

As the dragon was connected with the moon, and the moon with the bamboo, it might be expected that the dragon and bamboo would be closely linked. One of the holy men is credited with having reached the lunar heaven by cutting down a bamboo, which he afterwards transformed into a dragon. He rode heavenwards on the dragon’s back.

Saintly women, as a rule, rise to heaven in the form of birds, or in their own form, without wings, on account of the soul-like lightness of their bodies, which have become purified by performing religious rites and engaging in prayer and meditation. Their husbands have either to climb trees or great mountains. Some holy women, after reaching heaven, ride along the clouds on the back of the Kʼilin, the bisexual monster that the soul of Confucius is supposed to ride. It is a form of the dragon, but more like the makara of the Indian god Varuna than the typical “wonder beast” of China and Japan. Some of these monsters resemble lions, dogs, deer, walruses, or unicorns. They are all, however, varieties of the makara.

Sometimes we find that the attributes of the Great Mother, who, like Aphrodite, was a “Postponer of Old Age” (Ambologera), being the provider of the fruit of immortality and a personification of the World Tree, have been attached to the memory of some famous lady, and especially an empress. As the Egyptian Pharaoh, according to the beliefs of the solar cult, became Ra (the sun-god) after death, so did the Chinese empress become the “Royal Lady of the West”. Nu Kwa, a mythical empress of China, was reputed to have become a goddess after she had passed to the celestial regions. She figures in the Chinese Deluge Myth. Like the Babylonian Ishtar, she was opposed to the policy of destroying mankind. She did not, however, like Ishtar, content herself by expressing regret. When the demons of water and fire, aided by rebel generals of her empire, set out to destroy the world, Nu Kwa waged war against them. Her campaign was successful, but not until a gigantic warrior had partly destroyed the heavens by upsetting one of its pillars and the flood had covered a great portion of the earth. The empress stemmed the rising waters by means of charred reeds (a Babylonian touch), and afterwards rebuilt the broken pillar, under which was placed an Atlas-tortoise. Like Marduk (Merodach), she then set the Universe in order, and formed the channel for the Celestial River. Thereafter she created the guardians of the four quarters, placing the Black Tortoise in the north, and giving it control over winter; the Blue Dragon in the east, who was given control over spring; the White Tiger in the west, who was given control over autumn; and the Red Bird in the south, who was given control over summer, with the Golden Dragon, whose special duty was to guard the sun, the moon being protected by the White Deity of the west. The broken pillar of heaven was built up with stones coloured like the five gods.

Among the gifts conferred on mankind by this Empress-Goddess was jade, which she created so that they might be protected against evil influence and decay.

In this Deluge Myth, which is evidently of Babylonian origin, the gods figure as rebels and demons. The Mother Goddess is the protector of the Universe, and the friend of man. Evidently the cult of the Mother Goddess was at one time very powerful in China. In Japan the Empress Nu Kwa is remembered as Jokwa.

The Tree of Immortality, as has been seen, is closely associated with the Far Eastern Mother Goddess, who may appear before favoured mortals either as a beautiful woman, as a dragon, or as a woman riding on a dragon, or as half woman and half fish, or half woman and half serpent. It is from the goddess that the tree receives its “soul substance”; in a sense, she is the tree, as she is the moon and the pot of life-water, or the mead in the moon. The fruits of the tree are symbols of her as the mother, and the sap of the tree is her blood.

Reference has been made to Far Eastern stories about dragons transforming themselves into trees and trees becoming dragons. The tree was a “kupua” of the dragon. The mother of Adonis was a tree—Myrrha—the daughter of King Cinyras of Cyprus, who was transformed into a myrrh tree. A Japanese legend relates that a hero, named Manko, once saw a beautiful woman sitting on a tree-trunk that floated on the sea. She vanished suddenly. Manko had the tree taken into his boat, and found that the woman was hidden inside the trunk. She was a daughter of the Dragon King of Ocean.

GENII AT THE COURT OF SI WANG MU

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

A better-known Japanese tree hero is Momotaro (momo, peach, taro, eldest son), whose name is usually rendered in English as “Little Peachling”. He is known in folk-stories as a slayer of demons—a veritable Jack the Giant-Killer.

The legend runs that one day an old wood-cutter went out to gather firewood, while his wife washed dirty clothes in a river. After the woman had finished her work, she saw a gigantic peach drifting past. Seizing a pole, she brought it into shallow water, and thus secured it. The size of the peach astonished her greatly, and she carried it home, and, having washed it, placed it before her husband when he returned home for his evening meal. No sooner did the wood-cutter begin to cut open the peach than a baby boy emerged from the kernel. The couple, being childless, were greatly delighted, and looked upon the child as a gift from the Celestials, and they believed he had been sent so as to become their comfort and helper when they grew too old to work.

Momotaro, “the elder son of the peach”, as they called him, grew up to be a strong and valiant young man, who performed feats of strength that caused everyone to wonder at him.

There came a day when, to the sorrow of his foster-parents, he announced that he had resolved to leave home and go to the Isle of Demons, with purpose to secure a portion of their treasure. This seemed to be a perilous undertaking, and the old couple attempted to make him change his mind. Momotaro, however, laughed at their fears, and said: “Please make some millet dumplings for me. I shall need food for my journey.”

His foster-mother prepared the dumplings and muttered good wishes over them. Then Momotaro bade the old couple an affectionate farewell, and went on his way.

The young hero had not travelled far when he met a dog, which barked out: “Bow-wow! where are you going, Peach-son?”

“I am going to the Isle of Demons to obtain treasure,” the lad answered.

“Bow-wow! what are you carrying?”

“I am carrying millet dumplings that my mother made for me. No one in Japan can make better dumplings than these.”

“Bow-wow! give me one and I shall go with you to the Isle of Demons.”

The lad gave the dog a dumpling, and it followed at his heels.

Momotaro had not gone much farther when a monkey, perched on a tree, called out to him, saying: “Kia! Kia! where are you going, Son of a Peach?”

Momotaro answered the monkey as he had answered the dog. The monkey asked for a dumpling, promising to join the party, and when he received one he set off with the lad and the dog.

The next animal that hailed the lad was a pheasant, who called out: “Ken! Ken! where are you going, Son of a Peach?”

Momotaro told him, and the bird, having received the dumpling he asked for, accompanied the lad, the dog, and the monkey on the quest of treasure.

When the Island of Demons was reached they all went together towards the fortress in which the demon king resided. The pheasant flew inside to act as a spy. Then the monkey climbed over the wall and opened the gate, so that Momotaro and the dog were able to enter the fortress without difficulty. The demons, however, soon caught sight of the intruders, and attempted to kill them. Momotaro fought fiercely, assisted by the friendly animals, and slew or scattered in flight the demon warriors. Then they found their way into the royal palace and made Akandoji, the king of demons, their prisoner. This great demon was prepared to wield his terrible club of iron, but Momotaro, who was an expert in the jiu-jitsu system of wrestling, seized the demon king and threw him down, and, with the help of the monkey, bound him with a rope.

Momotaro threatened to put Akandoji to death if he would not reveal where his treasure was hidden.

The king bade his servants do homage to the Son of the Peach and to bring forth the treasure, which included the cap and coat of invisibility, magic jewels that controlled the ebb and flow of ocean, gems that shone in darkness and gave protection against all evil to those who wore them, tortoise-shell and jade charms, and a great quantity of gold and silver.

Momotaro took possession of as much of the treasure as he could carry, and returned home a very rich man. He built a great house, and lived in it with his foster-parents, who were given everything they desired as long as they lived.

In this story may be detected a mosaic of myths. The Egyptian Horus, whose island floated down the Nile, had white sandals which enabled him to go swiftly up and down the land of Egypt. There are references in the Pyramid Texts to his youthful exploits, but the full story of them has not yet been discovered. The Babylonian Tammuz, when a child, drifted in a “sunken boat” down the River Euphrates. No doubt this myth is the one attached to the memory of Sargon of Akkad,26 the son of a vestal virgin, who was placed in an ark and set adrift on the river. He was found by a gardener, and was afterwards raised to the kingship by the goddess Ishtar. Karna, the Aryo-Indian Hector, the son of Surya, the sun-god, and the virgin-princess Pritha, was similarly set adrift in an ark, and was rescued from the Ganges by a childless woman whose husband was a charioteer. The poor couple reared the future hero as their own son.27

Adonis, the son of the myrrh tree, was a Syrian form of Tammuz. Horus was the son of Osiris, whose body was enclosed by a tree after Set caused his death by setting him adrift in a chest. When Isis found the tree, which had been cut down for a pillar, the posthumous conception of the son of Osiris took place.28 The Momotaro legend has thus a long history.

The friendly animals figure in the folk-tales of many lands. Momotaro’s fight for the treasure, including the cloak of invisibility, bears a close resemblance to Siegfried’s fight for the treasure of the Nibelungs.29 In western European, as in Far Eastern lore, the treasure is guarded by dragons as well as by dwarfs and giants and other demons. When the dragon-slayer is not accompanied by friendly animals, he receives help and advice from birds whose language he acquires by eating a part of the dragon, or, as in the Egyptian tale, after getting possession of the book of spells, guarded by the “Deathless Snake”. When the Egyptian hero reads the spells he understands the language of birds, beasts, and fishes. The treasure-guarding dragon appears, as has been suggested, to have had origin in the belief that sharks were the guardians of pearl-beds and preyed upon the divers who stole their treasure.

The beliefs connected with the life-giving virtues of the tree of the Mother Goddess were attached to shells, pearls, gold, and jade. The goddess was the source of all life, and one of her forms was the dragon. As the dragon-mother she created or gave birth to the dragon-gods. Dragon-bones were ground down for medicinal purposes; dragon-herbs cured diseases; the sap of dragon-trees, like the fruit, promoted longevity, as did the jade which the goddess had created for mankind.

The beliefs connected with jade were similar to those connected with pearls, which were at a remote period emblems of the moon in Egypt. In China the moon was “the pearl of heaven”. One curious and widespread belief was that pearls were formed by rain-drops, or by drops of dew from the moon, the source of moisture, and especially of nectar or soma. Pearls and pearl-shells were used for medicinal purposes. They were, like the sap of trees, the very essence of life—the soul-substance of the Great Mother.30

That the complex ideas regarding shells, pearls, dew, trees, the moon, the sun, the stars, and the Great Mother were of “spontaneous generation” in many separated countries is difficult to believe. It is more probable that the culture-complexes enshrined in folk-tales and religious texts had a definite area of origin in which their history can be traced. The searchers for precious stones and metals and incense-bearing trees must have scattered their beliefs far and wide when they exploited locally-unappreciated forms of wealth.