CHAPTER XI

TREE-, HERB-, AND STONE-LORE

“Soul Substance” in Medicinal Plants—Life-fire in Water and Plants—“The Blood which is Life”—Colour Symbolism in East and West—Charm Symbolism—Gems as Fruit—Jade and Vegetation—Far Eastern Elixirs of Life—Links between Pine, Cypress, Mandrake, and Mugwort—Story of Treasure-finding Dog—The Far Eastern Artemis—Her Mugwort, Lotus, and Fruit Basket—Herbs and Pearl-shell—Goats and Women’s Herb—Chinese and Tartar’s Fight for Mandrake—Tea as an Elixir—Far Eastern Rip Van Winkles—Problem of the Date Tree—“Tree Tears” and “Stone Tears”—Weeping Deities—Goats and Thunder-gods—Goats and Sheep become Stones—Gems and Herbs connected with Moon—Graded Herbs, Deities, and Stones—Foreign Ideas in China.

In the ancient medical lore of China, as in the medical lores of other lands, there are laudatory references to “All-heal” plants and plants reputed to be specific remedies for various diseases. Not a few of these medicinal plants have been found to be either quite useless or positively harmful, but some are included in modern pharmacopœias, after having been submitted to the closest investigations of physiological science.

The old herbalists, witch-doctors, and hereditary “curers”, who made some genuine discoveries that have since been elaborated, were certainly not scientists in the modern sense of the term. Their “cures” were a quaint mixture of magic and religion. They searched for those plants and substances that appeared, either by their shape or colour, to contain in more concentrated form than others the “essence of life”, the “soul substance” that restored health and promoted longevity.

This “soul substance” was concentrated in body-odours and body-moistures. It was a something mixed in water which had colour, odour, and heat—a something derived from the Great Mother, who had herself sprung from water, as did the Egyptian Hathor and the Greek Aphrodite, or, if not directly from the Great Mother, from one or other of her offspring. The “soul substance” of the goddess was in vegetation; the sap of trees was identified with her blood—the “blood which is life”. Blood was one kind of body-moisture; other kinds were sweat, tears, saliva, &c. All these moistures had fertilizing properties. The Mother, as the sky-goddess, provided the world’s supply of fertilizing water. In China the supply was controlled by the dragon-gods, who caused the thunder and lightning that released the rain and flooded the rivers.

Winter is the Chinese dry season. It was believed that during this period the dragons were concealed and asleep. No growth was possible during winter because of the scarcity of water—the life-giving water that caused Nature to “renew her youth” in the spring season. When the dragons awoke and rose fighting and thundering, parched wastes were soaked and fertilized by rain. Then the old, decaying world renewed her youth and fresh vegetation appeared, because “soul substance” in the form of rain had entered the soil and furnished plants with “blood-sap”, and at the same time with vital energy, vital odours, and vital colours. Thus life, which had its origin in water, was sustained by the products of water and by the properties in water.

The plants that were supposed to store up most “soul substance” were those that grew in water, like the lotus, those that constantly absorbed moisture, like the “fungus of immortality”, or those that sprang up suddenly during a thunder-storm, like the “Red Cloud herb”. The latter required a heavy deluge to bring it into existence. It was a special gift of the dragon-god—or an “avatar” of that deity—and had concentrated in it the essence of much rain, and, in addition, the essence of lightning—the “fire of heaven”, ejected by the rain-dragon. The lightning was the “dragon’s tongue”, and had therefore substance, moisture, and heat, as well as brilliance. To the early thinkers the life fluid was not only blood, but warm blood—blood pulsating with the “vital spark”, the “fire of life”. These men would have accepted in the literal sense the imagery of the modern Irish poet, who wrote:

O, there was lightning in my blood,

Red lightning lighten’d through my blood,

My Dark Rosaleen.

The “fire of life” might be locked up in vegetation, in stone, or in red earth, and be made manifest by its colour alone.

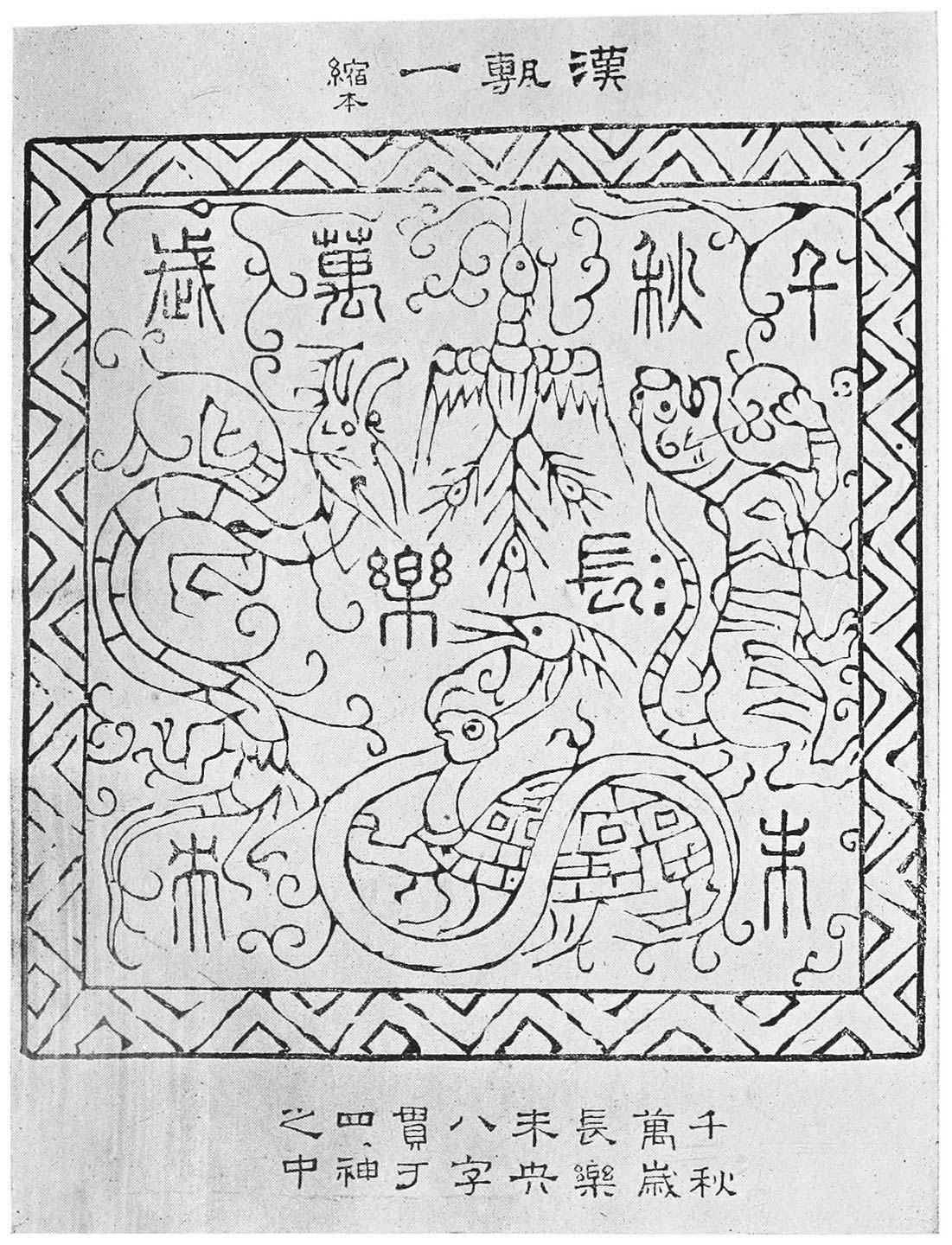

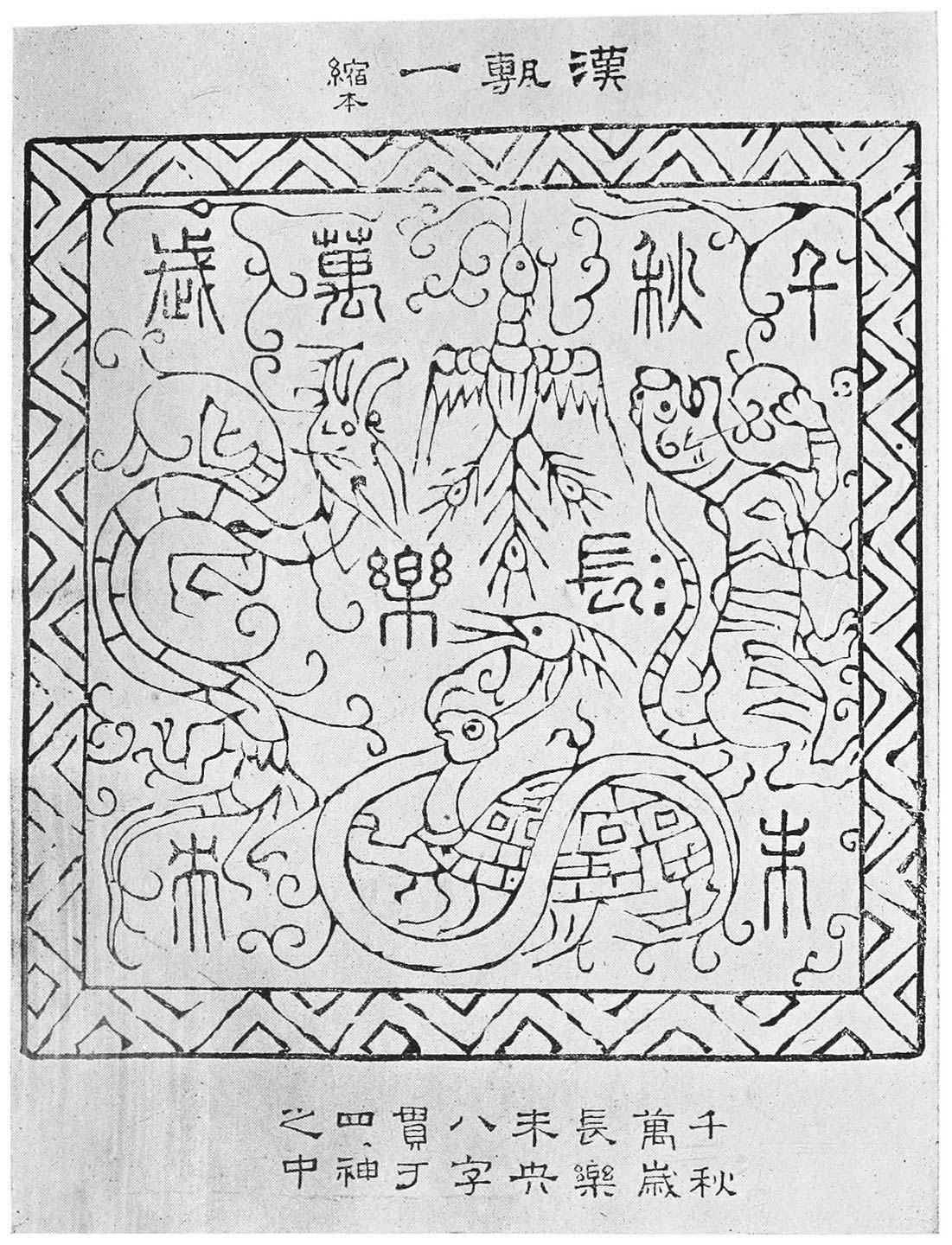

SQUARE BRICK OF THE HAN DYNASTY, WITH MYTHOLOGICAL FIGURES AND INSCRIPTIONS

The figures enclosed in the rectangular panel surrounded by a geometrical border represent the four quadrants of the Chinese uranoscope, being: 1. The Blue Dragon of the East. 2. The Black Warriors, Tortoise and Serpent of the North. 3. The Red Bird of the South. 4. The White Tiger of the West. The eight archaic characters filling in the intervals read: Chʼien chʼiu wan sui chʼang lo wei yang, “For a thousand autumns and a myriad years everlasting joy without end.”

The genesis of this idea can be traced at a very early period in the history of modern man (Homo sapiens). In Aurignacian times in western Europe (that is, from ten till twenty thousand years ago) blood was identified with life and consciousness. The red substance in “the blood which is life” was apparently regarded as the vitalizing agency, and was supposed to be the same as red earth (red ochre). It is found, from the evidence afforded by burial customs, that the Aurignacian race originated or perpetuated the habit of smearing the bodies of their dead with red ochre. After the flesh had decayed, the red ochre fell on and coloured the bones and the pebbles around the bones. Whether or not the red ochre was supposed to be impregnated with the essence of fire, or of the sun, the source of fire, it is impossible to say. Behind the corpse-painting custom there was, no doubt, a body of definite beliefs. As much is suggested by the fact that shell-amulets and spine-amulets were laid on or about the dead. The belief that the first man had been formed of red clay mixed with water may well have been in existence in Aurignacian times. The amulets associated with Aurignacian ceremonial burials suggest, too, that ideas had been formulated regarding the after-life. Was it believed that the painted, and therefore reanimated, body would rise again, or that the soul could be assisted to travel to the Otherworld? These questions cannot yet be answered. We can do no more than note here that Colour Symbolism, and especially Red Symbolism and all it entails, had origin in remote antiquity.

In China red flowers and red berries were supposed, because of their colour, to be strongly impregnated with “soul substance” or “vital essence”, or, to use the Chinese term, with shen. These flowers and berries had curative qualities. In western Europe the red holly berry was in like manner regarded as an “All-heal”. The tree on which the red berry appears is so full of divine life that it is an evergreen. In Gaelic folk-lore holly is associated with the Mother Goddess and with the water-beast (dragon) and its “avatar”, the red-spotted salmon, which is supposed to swallow the holly berries that drop into its pool.

The red substance which is in the blood was not necessarily confined, however, to vegetation. As it was of the earth, earthy, or a product of some mysterious agency at work in the earth, it might be found in coagulated form as a ruby, or any other red stone, or as a stone streaked or spotted with red; it might be found in water as a shell, wholly or partly red, or as a red or yellow pearl inside a shell. It might likewise be found concentrated in the red feathers of a bird. A bird with red feathers was usually recognized as a “thunder bird”—Robin Red-breast is a European “thunder bird”1—and the red berry as a “thunder berry”—a berry containing the “soul substance” of the god of lightning and fire. Fire was obtained by friction from trees associated with the divine Thunderer; his spirit dwelt in the tree. One of the “fire sticks” was invariably taken from a red-berried tree.

The red vital substance might likewise be displayed by a sacred fish—the “thunder fish”. In the Chinese “Boy Blue” story the thunder-dragon in human form rides on the back of a red carp.

Yellow is, like red, reputed to be a vital colour. Lightning is yellow; the flames of wood fires are yellow, while the embers are red. Early man appears to have recognized the close association of yellow and red in fire. Gold is yellow, and it was connected, as a substitute for red and yellow shells, with the sun, which at morning and evening sends forth red and yellow rays. The fire which is in the sun “warms the blood” and promotes the growth of plants, as does the moisture in the moon—the moon which controls the flow of sap and blood. The combination of sun-fire, lunar-fire, and moisture, or of fire-red earth and rain, constituted, according to early man’s way of thinking, the mystery called life. Yellow berries and yellow flowers were as sacred to him, and had as great life-prolonging and curative qualities, as red berries, red flowers, red feathers, and the skins and scales of red fish. Yellow gems and yellow metals were consequently valued as highly as were red gems and red metals. In China yellow is the earth colour. In Ceylon, Burmah, Tibet, and China it is the sacred colour of the Buddhists.

Blue, the sky colour, and therefore the colour of the sky-deity, was likewise holy. Torquoise and lapis-lazuli were connected with the Great Mother. The sacredness of green has a more complex history. It was not reverenced simply because of the greenness of vegetation. The mysterious substance that makes plants green was derived from the supreme source of life—the green form of the water-goddess or god—and was to be found in concentrated form in green gems and stones, including green jade. White was the colour of day, the stars, and the moon, and black the colour of night and of death, and therefore the colour of deities associated with darkness and the Otherworld. In China black is the colour of the north, of winter, and of drought. The combination of the five colours (black, white, red, yellow, and blue or green) was displayed by all deities. This conception is enshrined in the religious text which De Visser gives without comment:

“A dragon in the water covers himself with five colours;

Therefore he is a god.”2

In China, as in several other countries, the colour of an animal, plant, or stone was believed to reveal its character and attributes. A red berry was regarded with favour, because it displayed the life colour. A red stone was favoured for the same reason. When it is nowadays found that some particular berry or herb, favoured of old as an “All-heal”, is really an efficacious medicine, an enthusiast may incline to regard it as a wonderful thing that modern medical science has not achieved, in some lines, greater triumphs than were achieved by the “simple observers” of ancient times. But it may be that the real cures were of accidental discovery, and that the effective berry or herb would, on account of its colour alone, have continued in use whether it had cured or not.

In China not only the berry with a “good colour” was used by “curers”, but even the stone with a “good colour”. The physicians, for instance, sometimes prescribed ground jade, and we read of men who died, because, as it was thought, the quantities of jade-medicine taken were much too large. Some ancient writers assert, in this connection, that although a dose of ground jade may bring this life to a speedy end, it will ensure prolonged life in the next world.

The berries and stones which were reputed to be “All-heals” were not always devoured. They could be used simply as charms. The vital essence or “soul substance” in berry or stone was supposed to be so powerful that it warded off the attacks of the demons of disease, or expelled the demons after they had taken possession of a patient. Medicines might be prepared by simply dipping the charms into pure well water. These charms were often worn as body-ornaments. All the ancient personal ornaments were magic charms that gave protection or regulated the functions of body organs. When symbols were carved on jade, the ornaments were believed to acquire increased effectiveness. Gold ornaments were invariably given symbolic shape. Like the horse-shoe, which in western Europe is nailed on a door for “luck”—that is, to ward off evil—these symbolic ornaments were credited with luck-bringing virtues. The most ancient gold ornaments in the world are found in Egypt, and these are models of shells, which had been worn as “luck-bringers” long before gold was worked.3 These shells had an intimate association with the Mother Goddess, who, in one of her aspects, personified the birth-aiding and fertilizing shell.

The idea that the coloured fruits and the coloured stones were life-giving “avatars” of the Mother Goddess is well illustrated in the glowing accounts of the Chinese Paradise. The Tree of Life might bear fruit or gems. The souls swallowed gems as readily as fruit. In the Japanese Paradise the immortals devour powdered mother-of-pearl shells as well as peaches, dried cassia pods, cinnabar, pine needles, or pine cones.

Jade was connected with vegetation on this earth as well as in Paradise. As we have seen, the Great Mother goddess created this famous mineral for the benefit of mankind. It contained her “soul substance”, as did the trees, their blossoms, and their fruit, and even their leaves and bark. This quaint belief is enshrined in the following quotation from the Illustrated Mirror of Jades, translated by Laufer and given without comment:

“In the second month, the plants in the mountains receive a bright lustre. When their leaves fall, they change into jade. The spirit of jade is like a beautiful woman.”4

It is obvious that the “beautiful woman” is the Goddess of the West. Reference to coral trees in Paradise are numerous. It was believed not only in China but in western Europe, until comparatively recent times, that coral was a marine tree—the tree of the water-goddess. The Great Mother was connected with the water above and beyond the firmament, as well as the rivers and the sea.

“Good health” in the Otherworld was immortality or great longevity. A soul which ate of a peach from the World Tree was assured of 3000 years of good health. He renewed his youth, and never grew old, so long as the supply of peaches was assured.5

In China men lengthened their days by partaking of “soul substance” in various forms. The pine-tree cult made decoctions of pine needles and cones, or of the fungus found at the roots of pines. “The juice of the pine”, says one Chinese sage, “when consumed for a long time, renders the body light, prevents man from growing old, and lengthens his life. Its leaves preserve the interior of the body; they cause a man never to feel hunger, and increase the years of his life.” The cypress was also favoured. “Cypress seeds,” the same writer asserts, “if consumed for a long period, render a man hale and healthy. They endow him with a good colour, sharpen his ears and eyes, cause him never to experience the feeling of hunger, nor to grow old.” The camphor tree comes next to the pine and cypress as “a dispenser and depository of vital power”.6

Apparently the fact that pines and cypresses are evergreens recommended them to the Chinese, although it was not for that reason only the belief arose about their richness of “soul substance”. An ancient Chinese sage has declared: “Pines and cypresses alone on this earth are endowed with life, in the midst of winter as well as in summer they are evergreen. Pines 1000 years old resemble a blue ox, a blue dog, or a blue human being. Cypresses 1000 years old have deep roots shaped like men in a sitting posture.… When they are cut they lose blood.… Branches of pines which are 3000 years old have underneath the bark accumulations of resin in the shape of dragons, which, if pounded and consumed in a quantity of full ten pounds, will enable a man to live 500 years.”7

Here we have the tree connected with the blue dragon. As has been stated, ancient pines were transformed into dragons. The assertion that the pines and cypresses were the only trees possessed of “vital power” does not accord with the evidence regarding the peach-tree cult. The peach, although not an evergreen, was credited with being possessed of much “soul substance”.

No doubt the ideas connected with evergreens had a close association with the doctrines of colour symbolism. The Chinese “Tree of Heaven” (Ailanthus glandulosa) appears to have attracted special attention, because in spring its leaves are coloured reddish-violet or reddish-brown before they turn green. The walnut, cherry, and peony similarly show reddish young leaves, and these trees have much lore connected with them.

One seems to detect traces of the beliefs connected with the mandrake in the reference to the human-shaped roots of the 1000-year-old cypress tree. The mandrake was the plant of Aphrodite, and its root, which resembles the human form, was used medicinally; it has narcotic properties, and was believed also to be a medicine which promoted fertility, assisted birth, and caused youths and girls to fall in love with one another. According to mandrake-lore, the plant shrieks when taken from the earth, and causes the death of the one who plucks it.8 Dogs were consequently employed to drag it out of the ground, and they expired immediately. The “mandrake apple” is believed by Dr. Rendel Harris to have been the original “love apple”.9

In like manner the mugwort, the plant of Artemis, was connected in China and Japan with the pine which had virtues similar to those of the herb. Although the mandrake-dog is not associated with the cypress, it is found connected in a Japanese folk-story with the pine. The hero of the tale, an old man called Hana Saka Jijii, acquired the secret how to make withered trees blossom. He possessed a wonderful dog, named Shiro, which one day attracted his attention by sniffing, barking, and wagging his tail at a certain spot in the cottage garden. The old man was puzzled to know what curious thing in the ground attracted the dog, and began to dig. After turning up a few spadefuls of earth he found a hoard of gold and silver pieces.

CHINESE BOWL WITH SYMBOL OF LONGEVITY

(Victoria and Albert Museum)

A jealous neighbour, having observed what had happened, borrowed Shiro and set the animal to search for treasure in his own garden. The dog began to sniff and bark at a certain spot, but when the man turned over the soil, he found only dirt and offal that emitted an offensive smell. Angry at being deceived by the dog, he killed it and buried the body below the roots of a pine tree. Hana Saka Jijii was much distressed on account of the loss of Shiro. He burned incense below the pine tree, laid flowers on the dog’s grave, and shed tears. That night he dreamed a wonderful dream. The ghost of Shiro appeared before him, and, addressing him, said: “Cut down the pine tree above my grave and make a rice mortar of it. When you use the mortar think of me.”

The old man did as the dog advised, and discovered to his great joy that when he used the pine-tree mortar each grain of rice was transformed into pure gold. He soon became rich.

The envious neighbour discovered what was going on and borrowed the mortar. In his hands, however, it turned rice into dirt. This enraged him so greatly that he broke the mortar and burned it.

That night the ghost of Shiro appeared once again in a dream, and advised Hana Saka Jijii to collect the ashes of the burnt mortar and scatter them on withered trees. Next morning he did as the dog advised him. To his astonishment he found that the ashes caused withered trees to come to life and send forth fresh and beautiful blossoms. He then went about the country and employed himself reviving dead plum and cherry trees, and soon became so renowned that a prince sent for him, asking that he should bring back to life the withered trees in his garden. The old man received a rich reward when he accomplished the feat.

The jealous neighbour came to know how Hana Saka Jijii revived dead trees, so he collected what remained of the ashes of the pine-tree mortar. Then he set forth to proclaim to the inhabitants of a royal town that he could work the same miracle as Hana Saka Jijii. The prince sent for him, and the man climbed into the branches of a withered tree. But when he scattered the ashes no bud or blossom appeared, and the wind blew the dust into the eyes of the prince and nearly blinded him. The impostor was seized and soundly beaten; and the dog Shiro was, in this manner, well avenged.

In this story the dog is a searcher for and giver of treasure. It is of special interest, therefore, to find that Artemis, the mugwort-goddess of the West, “was not only the opener of treasure-houses, but she also possessed the secret of the Philosopher’s Stone; she could transmute base substances into gold”. She could therefore grant riches to those whom she favoured. Dr. Rendel Harris, quoting from an old English writer, records the belief “that upon St. John’s eve there are coals (which turn to gold) to be found at midday under the roots of mugwort, which after or before that time are very small, or none at all”. The gold cures sickness.10

A similar belief was attached to the mandrake. A French story tells of a peasant who regularly “fed” a mandrake that grew below a mistletoe-bearing oak. The mandrake, when fed, would, it was believed, “make you rich by returning twice as much as you spent upon it.… The plant had become an animal.”11

If Shiro’s prototype was the mandrake-dog which sacrificed itself for the sake of lovers, and was itself an “avatar” of the deity, we should expect to find the pine tree connected with the love-goddess.12 Joly, in his Legend in Japanese Art (p. 147), tells that “at Takasago there is a very old pine tree, the trunk of which is bifurcated; in it dwells the spirit of the Maiden of Takasago, who was seen once by the son of Izanagi, who fell in love and wedded her. Both lived to a very great age, dying at the same hour on the same day, and since then their spirits abide in the tree, but on moonlight nights they return to human shape and revisit the scene of their earthly life and pursue their work of gathering pine needles.” The needles were promoters of longevity, as we have seen.

Another Japanese pair associated with the pine trees are Jo and Uba, a couple of old and wrinkled spirits. They gathered pine needles, Jo using a rake and Uba a besom and fan.

The goddess of the pine was evidently a Far Eastern Aphrodite, as well as a Far Eastern Artemis—an Artemis who provided medicine for women in the form of the mugwort, was a goddess of birth, a guardian of treasure, and a goddess of travellers and hunters. The Romans associated with Diana (Artemis) her loved one, Dianus or Janus,13 as the tree-goddess in Japan was associated with a deified human lover.

The pine may have been “a kind of mugwort” (and apparently, like the cypress, a “kind of mandrake”), but it did not displace the mugwort as a medicinal plant. Dr. Rendel Harris quotes a letter from Professor Giles, the distinguished Chinese scholar, who says: “There is quite a literature about Artemisia vulgaris, L. (the mugwort), which has been used in China from time immemorial for cauterizing as a counter-irritant, especially in cases of gout. Other species of Artemisia are also found in China.”14

The Far Eastern Artemis appears to be represented by the immortal lady known in China as Ho Sien Ku, and in Japan as Kasenko. She is shown “as a young woman clothed in mugwort, holding a lotus stem and flower” (like a western Asiatic or Egyptian goddess), “and talking to a phœnix”, or “depicted carrying a basket of loquat fruits which she gathered for her sick mother. She was a woman who, having been promised immortality in a dream, fed on mother-of-pearl, and thereafter moved as swiftly as a bird.”15 The Mexican god Tlaloc’s wife was similarly a mugwort goddess.

In the pine-tree story the Japanese representative of the tree- and lunar-goddess of love appears with her spouse on moonlight nights. The moon was the “Pearl of Heaven”. It will be noted that the mugwort is connected with pearl-shell—the lady Ho Sien Ku having acquired the right to wear mugwort, in her character as an immortal, by eating mother-of-pearl. This connection of pearl-shell with a medicinal plant is a more arbitrary one than that of the mugwort with the pine, or the mandrake with the cypress.

The lotus was a form of the ancient love-goddess, as was also the cowry. In Egypt the solar-god Horus emerges at birth from the lotus-form of Hathor as it floats on the breast of the Nile. Ho Sien Ku’s basket of fruit is also symbolic. “A basket of sycamore figs” was in Ancient Egypt “originally the hieroglyphic sign for a woman, a goddess, or a mother”. It had thus the same significance as the Pot, the lotus, the mandrake-apple, and the pomegranate. The latter symbol supplanted the Egyptian lotus in the Ægean area.16

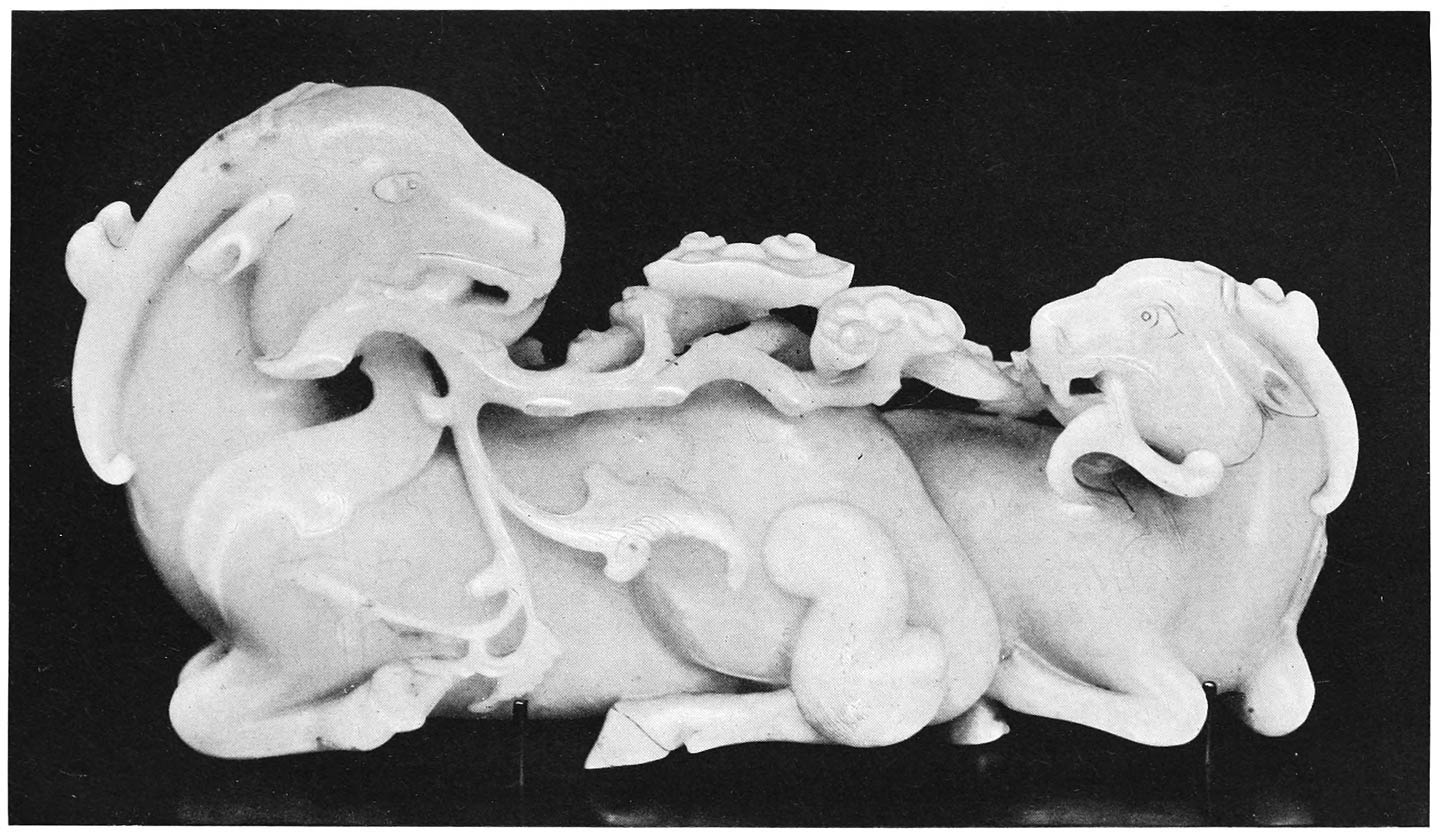

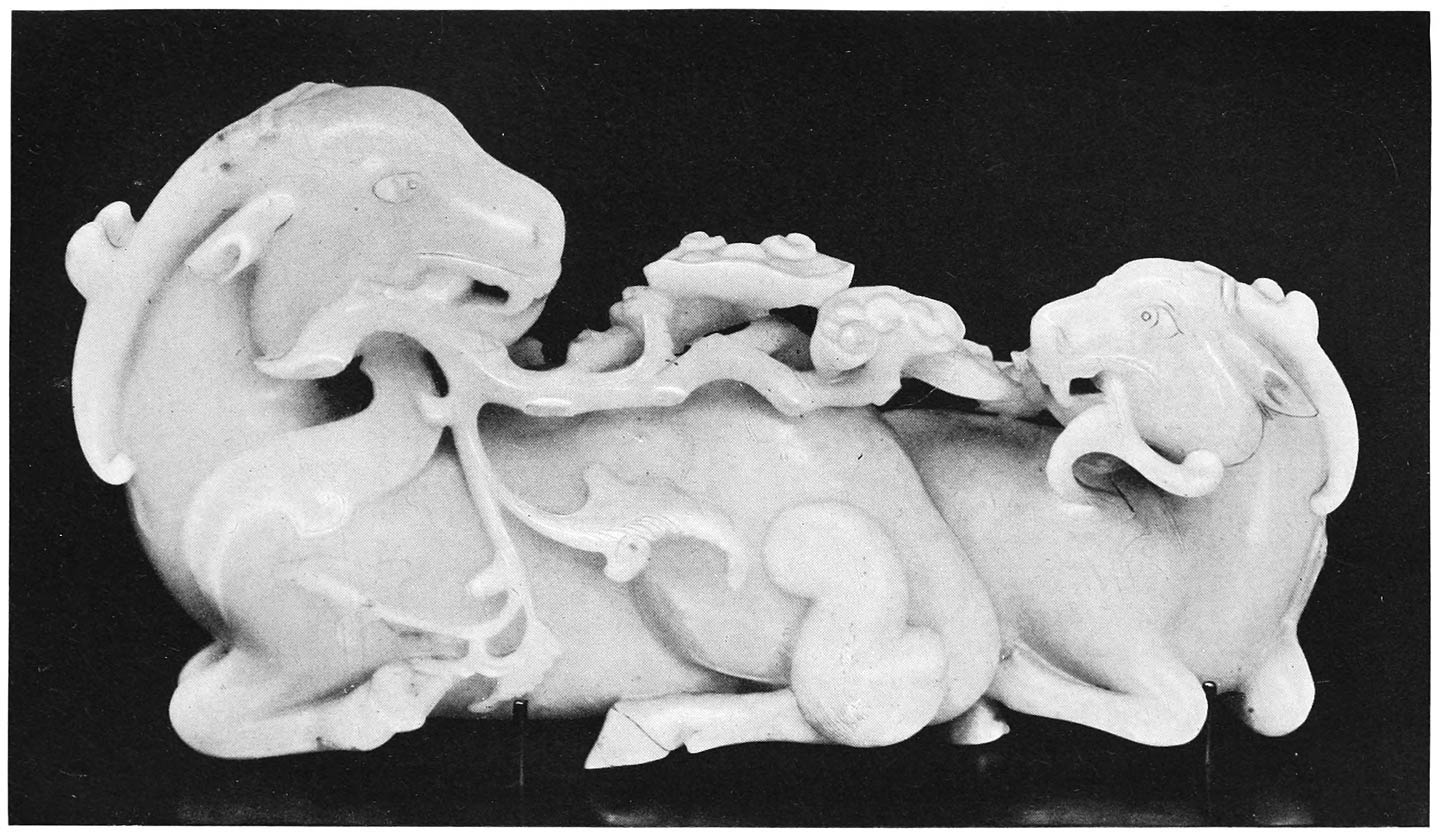

GOATS CROPPING PLANT OF LIFE

From the jade sculpture in the Scottish National Museum, Edinburgh

Mugwort, as already stated, was a medicine, and chiefly a woman’s medicine. “The plant (mugwort)”, says Dr. Rendel Harris, “is Artemis, and Artemis is the plant. Artemis is a woman’s goddess and a maid’s goddess, because she was a woman’s medicine and a maid’s medicine.”17 The mugwort promoted child-birth, and controlled women like the moon, and was used for women’s ailments in general. It was a healing plant, and was “good for gout” among other troubles.

The women’s herb in China is called the “san tsi”. An eighteenth-century writer18 says it is “efficacious in women’s disorders and hæmorrhages of all sorts”. It is found “only on the tops of high, steep mountains”, as is the scented Edelraut (Artemisia mutellina) an alpine plant like the famous and beautiful Edelweiss.

Continuing his account of the “san tsi” herb, the eighteenth-century writer and compiler says: “A kind of goat of a greyish colour is very fond of feeding upon this plant, insomuch that they (the Chinese) imagine the blood of this animal is endowed with the same medicinal properties. It is certain that the blood of these goats has surprising success against the injuries received by falls from horses, and other accidents of the same kind. This the missionaries have had experience of several times. One of their servants that was thrown by a vicious horse, and who lay some time without speech or motion, was so soon recovered by this remedy that the next day he was able to pursue his journey.” It is also “a specific against the smallpox”. The author of The Chinese Traveller, touching again on the blood substitute for this plant, which is “not easy to be had”, says: “In the experiments above mentioned, the blood of a goat was made use of that had been taken by hunters”.

The goat appears to be the link between Artemis “the curer” and Artemis as “Diana the huntress”. As the virtues of rare curative herbs passed into the blood of animals who ate them, the goddess, like her worshippers, hunted the animals in question, or became their protector. Pliny, in his twenty-eighth book, having, as Dr. Rendel Harris notes, “exhausted the herbals”, shows that “a larger medicine is to be found in animals and in man”.19

In China the stag or deer, the stork, and the tortoise are associated with the Tree of Life as “emblems of longevity”. One is reminded in this connection of the Western, Eastern, and Far Eastern legends about birds that pluck and carry to human beings leaves of “the plant of life” or “fungus of immortality”, and of Mykenæan and Ancient Egyptian representations of bulls, goats, deer, &c., browsing on vines and other trees or bushes that were supposed to contain the elixir of life, being sacred to the goddess and shown as symbols of her or of the god with whom she was associated as mother or spouse.

Another famous Far Eastern curative “wort” is the ginseng. Like the fungus of immortality, it grew on one of the Islands of the Blest. Taken with mermaid’s flesh, it was supposed to lengthen the life of man for several centuries.

“As described by Father Jartoux”, says the eighteenth-century English writer, already quoted,20 “it has a white root, somewhat knotty, about half as thick as one’s little finger; and as it frequently parts into two branches, not unlike the forked parts of a man, it is said from thence to have obtained the name of ginseng, which implies a resemblance of the human form, though indeed it has no more of such a likeness than is usual among other roots. From the root arises a perfectly smooth and roundish stem, of a pretty deep-red colour, except towards the surface of the ground, where it is somewhat whiter. At the top of the stem is a sort of joint or knot, formed by the shooting out of four branches, sometimes more, sometimes less, which spread as from a centre. The colour of the branches underneath is green, with a whitish mixture, and the upper part is of a deep red like the stem.… Each branch has five leaves,” and the leaves “make a circular figure nearly parallel to the surface of the earth”. The berries are of “a beautiful red colour”.

Here we have hints of the mandrake without a doubt. As a matter of fact, the ginseng has been identified with the mandrake. The plant evidently attracted attention because of its colours and form. As it has a red stem and red berries, it is not surprising to learn that “it strengthens the vital spirits, is good against dizziness in the head and dimness of sight, and prolongs life to extreme old age”, and that “those who are in health often use it to render themselves more strong and vigorous”. The four-leaved ginseng, like the four-leaved clover, was apparently a symbol of the four cardinal points. Its “five leaves” and the “circular figure formed by them” must have attracted those who selected five colours for their gods and adored the sun.

The ginseng is found “on the declivities of mountains covered with thick forests, upon the banks of torrents or about the roots of trees, and amidst a thousand other different forms of vegetables”.

Conflicts took place between Tartars and Chinese for possession of the ginseng, and one Tartar king had “the whole province where the ginseng grows encompassed by wooden palisades”. Guards patrolled about “to hinder the Chinese from searching for it (ginseng)”.

Tea first came into use in China as a life-prolonger. The shrub is an evergreen, and appears to have attracted the attention of the Chinese herbalists on that account. Our eighteenth-century writer says: “As to the properties of tea, they are very much controverted by our physicians; but the Chinese reckon it an excellent diluter and purifier of the blood, a great strengthener of the brain and stomach, a promoter of digestion, perspiration, and cleanser of the veins and urethra”. Large quantities of tea were in China given “in fevers and some sorts of colics”. Our author adds: “That the gout and stone are unknown in China is ascribed to the use of this plant”.21

Apparently we owe not only some valuable medicines, but even the familiar cup of tea, to the ancient searchers for the elixir of life and curative herbs. Intoxicating liquors (aqua vitæ, i.e. “water of life”) have a similar history. They were supposed to impart vigour to the body and prolong life. Withal, like the intoxicating “soma”, drunk by Aryo-Indian priests, they had a religious value as they produced “prophetic states”. Even the opium habit had a religious origin. Aqua vitæ was impregnated with “soul substance”, as was the juice of grapes, or, as the Hebrews put it, “the blood of grapes”.22

As Far Eastern beliefs associated with curative plants and curative stones (like jade) have filtered westward, so did Western beliefs filter eastward. Dr. Rendel Harris has shown that myths and beliefs connected with the ivy and mugwort, which were so prevalent in Ancient Greece, can be traced across Siberia to Kamschatka. The Ainus of Japan regard the mistletoe as an “All-heal”, as did the ancient Europeans. “The discovery of the primitive sanctity of ivy, mugwort, and mistletoe”, says Dr. Harris, “makes a strong link between the early Greeks and other early peoples both East and West, and it is probable that we shall find many more contacts between peoples that, as far as geography and culture go, are altogether remote.”23

There are many Far Eastern stories about men and women who have escaped threatened death by eating herbs, or pine resin, or some magic fruit.

One herb, called huchu, was first discovered to have special virtues by a man who, when crossing a mountain, fell into a deep declivity and was unable to get out of it, not only on account of the injuries he had sustained, but because the rocks were as smooth as glass. He looked about for something to eat, and saw only the huchu herb. Plucking it out of the thin soil in which it grew, he chewed the root and found that it kept his body at a temperature which prevented him feeling cold, while it also satisfied his desire for food and water. Time passed quickly and pleasantly. He felt happy, slept well, and did not weary.

One day the earth was shaken by a great earthquake that opened a way of escape for him. The man at once left his mountain prison and set off for home.

On reaching his house he found, to his surprise, that it was inhabited by strangers. He spoke to them, asking why they were there, and inquiring regarding his wife and children. The strangers only scoffed at him. Then he wandered through the village, searching for old friends, but could not find one. He, however, interested a wise old man in his case. An examination was made of the family annals, and it was discovered that the name given by the man had been recorded three centuries earlier as that of a member of the family who had mysteriously disappeared.

The Chinese Rip Van Winkle then told the story of his life in the mountain cavity, and how he had been sustained by the huchu herb. In this manner, according to Chinese tradition, the discovery was made that the herb “prolongs life, cures baldness, turns grey hair black again, and tends to renew one’s youth”. Great quantities of huchu tea must be drunk for a considerable time, and no other food taken, if the desired results are to be fully achieved.

Other Rip Van Winkle stories tell of men who have lived for centuries while conversing with immortals met by chance, or while taking part in their amusements like the men in Western European stories, who enter fairy knolls and dance with fairy women, and think they have danced for a single hour, but find, when they come out, that a whole year has gone past.

One day a Taoist priest, named Wang Chih, entered a mountain forest to gather firewood. He came to a cave in which sat two aged men playing chess, while others looked on. The game fascinated Wang Chih, so he entered the cave, laid aside his chopper, and looked on. When he began to feel hungry and thirsty he moved as if to rise up and go away, although the game had not come to an end. One of the spectators, however, divining his intention, handed him a kernel, which looked like a date stone, saying, “Suck that”.

Wang Chih put the kernel in his mouth and found that it refreshed him so that he experienced no further desire for food or drink.

The chess-playing continued in silence, and several hours, as it seemed, flew past. Then one of the old men spoke to Wang Chih, saying: “It is now a long time since you came to join our company. I think you should return home.”

Wang Chih rose to his feet. When he grasped his chopper he was astonished to find that the handle crumbled to dust. On reaching home, he discovered, like the man who fed on the huchu herb, that he had been missing for one or two centuries. The old men with whom he had mingled in the cave were the immortals, known to the Chinese as Sten Nung, to the Japanese as Sennin, and to the Indians as Rishis—a class of demi-gods who once lived on earth and achieved great merit, in the spiritual sense, by practising austerities in solitude and for long periods.

The reference to the date stone is of special interest. In Babylonia and Assyria the date palm was one of the holy trees. It was cultivated in southern Persia, and may have been introduced into China from that quarter. Another possibility is that the seeds were got from dates carried by Arab traders to China, or obtained from Arabs by Chinese traders. One of the Chinese names for the date resembles the Ancient Egyptian designation, bunnu. Laufer, who discusses this problem,24 refers to early Chinese texts that make mention of Mo-lin, a distant country in which dark-complexioned natives subsist on dates. Mo-lin, earlier Mwa-lin, is, Laufer thinks, “intended for the Malindi of Edrīsī or Mulanda of Yãqūt, now Malindi, south of the Equator, in Seyidieh Province of British East Africa”. The lore connected with other Trees of Life in China appears to have been transferred to the imported date palm. One of its names is “jujube of a thousand years”, or “jujube of ten thousand years”. Laufer quotes a Chinese description of the date palm which emphasizes the fact that it “remains ever green”, and tells that “when the kernel ripens, the seeds are black. In their appearance they resemble dried jujubes. They are good to eat, and as sweet as candy.”25

Another Chinese Rip Van Winkle story relates that two men who wandered among the mountains met two pretty girls. They were entertained by them, and fed on a concoction prepared from hemp. Seven generations went past while they enjoyed the company of the girls.

The hemp (old Persian and Sanskrit bangha) was cultivated at a remote period in China and Iran. A drug prepared from the seed is supposed to prolong life and to inspire those who partake of it to prophesy, after seeing visions and dreaming dreams. The “bang” habit is as bad as the opium habit.

In the tree-lore of China there are interesting links between trees and stones. It has been shown that jade was an “avatar” of the mother-goddess, who created it for the benefit of mankind; that tree foliage was identified with jade; that dragons were born from stones; certain coloured stones were “dragon eggs”, the eggs of the “Dragon Mother”, the mother-goddess herself, who had “many forms and many colours”. Sacred stones were supposed to have dropped from the sky, or to have grown in the earth. Pliny refers to a stone that fell from the sun.

In Ancient Egypt it was believed that the creative or fertilizing tears of the beneficent deities, like those of Osiris and Isis, caused good shrubs to spring up, and that the tears of a deity like Set, who became the personification of evil, produced poisonous plants. The weeping Prajapati of the Aryo-Indians resembles the weeping sun-god Ra of Egypt. At the beginning, Prajapati’s tears fell into the water and “became the air”, and the tears he “wiped away, upwards, became the sky”.26

It is evident that the idea of the weeping deity reached China, for there are references to “tree tears” and to “stone tears”. Both the tree and stone “avatars” of the Great Mother or Great Father shed creative tears.

The Chinese appear to have discovered their wonderful “weeping tree” in Turkestan in the second century B.C., but the beliefs connected with it were evidently of greater antiquity. They already knew about the weeping deities who created good and baneful vegetation, and the discovery of the tree, it would appear, simply afforded proof to them of the truth of their beliefs.

The tree in question (the hu tʼun tree) has been identified by Laufer as the balsam poplar. “This tree”, he quotes from a Chinese commentator, “is punctured by insects, whereupon flows down a juice, that is commonly termed hu tʼun lei (‘hu tʼun tears’), because it is said to resemble human tears. When this substance penetrates earth or stone it coagulates into a solid mass, somewhat on the order of rock salt.” Laufer notes that Pliny “speaks of a thorny shrub in Ariana, on the borders of India, valuable for its tears, resembling the myrrh, but difficult of access on account of the adhering thorns. It is not known what plant is to be understood by the Plinian text; but the analogy of the tears,” comments Laufer, “with the above Chinese term is noteworthy.”

An ancient Chinese scholar, dealing with the references to the weeping trees, says that “its sap sinks into the earth, and is similar to earth and stone. It is used as a dye, like the ginger stone” (a variety of stalactite). Ta Min, who lived in the tenth century of our era, wrote regarding the tree, “There are two kinds—a tree sap, which is not employed in the Pharmacopœia, and a stone sap collected on the surface of stones; this one only is utilized as medicine. It resembles in appearance small pieces of stone, and those coloured like loess take the first place. The latter was employed as a remedy for toothache.”27

In Babylonia toothache was supposed to be caused by the marsh-worm demon which devours “the blood of the teeth” and “destroys the strength of the gums”. The god Ea smites the worm, which is a form of the dragon Tiamat.28

The antique conception enshrined in the “weeping tree” is that the mother-goddess of the sky sheds tears, which cause the tree to grow, and that, as the tree, she sheds tears that become stones, while the stones shed tears that provide soul substance to cure disease by removing pain and promoting health. In Egypt the stone specially sacred to the sky-goddess Hathor was the turquoise, in which was, apparently, concentrated the vital essence or “soul substance” of the sky. The goddess sprang from water, and her tears were drops of the primeval water from which all things that are issued forth. Those stones that contained water were in China “dragon stones” or “dragon eggs”. In various countries there are legends about deities, and men and women have sprung from moisture-shedding stones. The mother-goddess of Scotland, who presides over the winter season, transforms herself at the beginning of summer into a stone that is often seen to be covered with moisture. In Norse mythology the earliest gods spring from stones that have been licked by the primeval mother-cow. Mithra of Persia sprang from a rock. Indonesian beliefs regarding moist stones, from which issue water and human beings, are fairly common.29

The Kayan of Sumatra are familiar with the beliefs that connect stones and vegetables with the sky and water. They say that “in the beginning there was a rock. On this rain fell and gave rise to moss, and the worms, aided by the dung beetles, made soil by their castings. Then a sword handle came down from the sun and became a large tree. From the moon came a creeper which, hanging from the tree, mated through the action of the wind.” From this union of tree and creeper, i.e. sun and moon, “the first men were produced”.30

The connection between sky, plant, and animals is found in the lore regarding the Chinese sant si mountain herb which is eaten by goats. This herb, like other herbs, is produced from the body-moisture of the goddess; it is the goddess herself—the goddess who sprang from water. The plant is guarded by the mountain goat as the pearls are guarded by the shark, and the goat, which browses on the plant, is, like the shark, an avatar of the goddess. Goat’s blood is therefore as efficacious as the sap of the herb.

The goat or ram is the vehicle of the Indian fire and lightning god Agni; the Norse god Thor has a car drawn by goats. Dionysos, as Bromios (the Thunderer), has a goat “avatar”, too, and he is the god of wine (Bacchus)—the wine, the “blood of grapes”, being the elixir of life. Osiris, who had a ram form, was to the Ancient Egyptians “Lord of the Overflowing Wine”. European witches ride naked on goats or on brooms; the devil had a goat form.

In China, as has been shown, the dragon-herb, peach, vine, pine, fungus of immortality, ginseng, &c., received their sap, or blood, or “soul substance” from rain released by dragon gods, who thundered like Bromios-Dionysos. The inexhaustible pot from which life-giving water came was in the moon. This Pot was the mother-goddess, who had a star form. A fertilizing tear from the goddess-star, which falls on the “Night of the Drop”, is still supposed in Egypt to cause the Nile to rise in flood.

We should expect to find the Chinese mythological cycle completed by an arbitrary connection between the goat or ram and sacred stones.

There are, to begin with, celestial goats. Some of the Far Eastern demi-gods, already referred to, ride through “Cloud-land” on the backs of goats or sheep. One of the eight demi-gods, who personify the eight points of the compass, is called by the Chinese Hwang Chʼu-Pʼing, and by the Japanese Koshohei. He is said to be an incarnation of the “rain-priest”, Chʼih Sung Tze, who has for his wife a daughter of the Royal Mother of the West, the mother-goddess of the Peach Tree of Life.

The Japanese version of the legend of the famous Koshohei is given by Joly as follows: “Koshohei, when fifteen years old, led his herd of goats to the Kin Hwa mountains, and, having found a grotto, stayed there for forty years in meditation. His brother, Shoki, was a priest, and he vowed to find the missing shepherd. Once he walked near the mountain and he was told of the recluse by a sage named Zenju, and set out to find him. He recognized his brother, but expressed his astonishment at the absence of sheep or goats. Koshohei thereupon touched with his staff the white stones with which the ground was strewn, and as he touched them they became alive in the shape of goats.”31

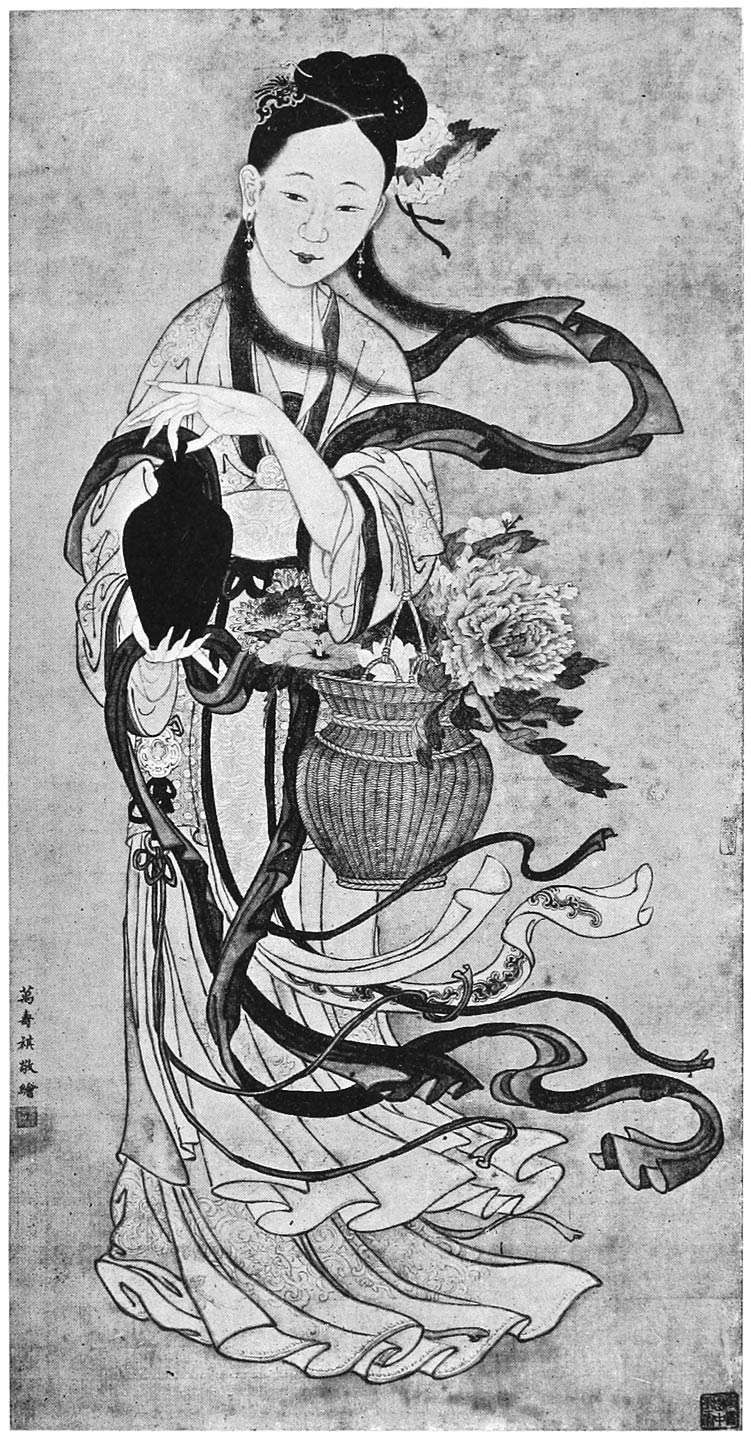

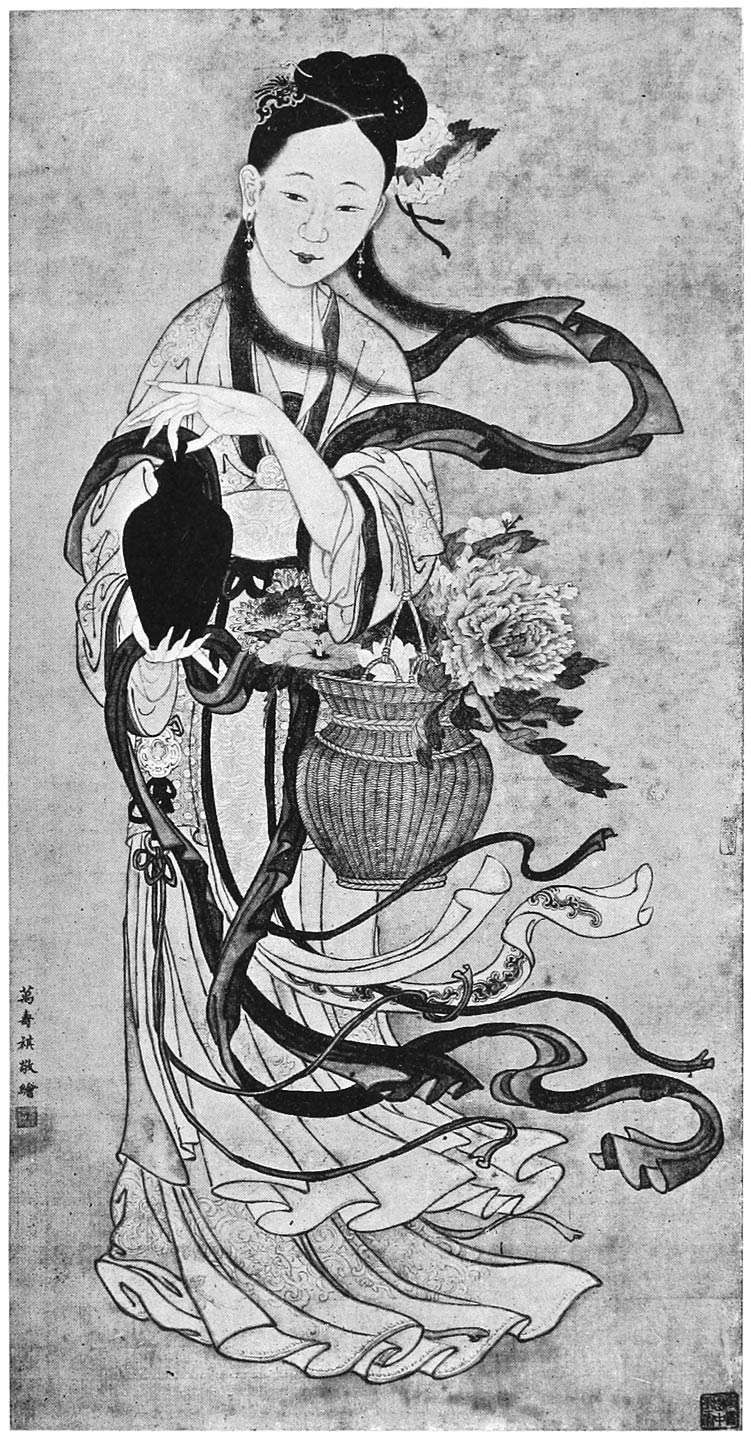

THE GODDESS OF THE DEW

From a Chinese painting in the British Museum

Goats might become stones. The Great Mother was a stone, rock, or mountain, having the power to assume many forms, because she was the life of all things and the substance of all things. The goddess was the Mountain of Dawn in labour that brought forth the mouse-form of the sun (Smintheus Apollo), or the antelope form of the sun, or the hawk or eagle form, or the human form, or the egg containing the sun-god. She was also the sun-boat—the dragon-ship of the sun. The five holy mountains of China appear to have been originally connected with the goddess and her sons—the gods of the four quarters.

In China deities might on occasion take the form of stones or reptiles. During the Chou Dynasty (756 B.C.) “one of the feudal dukes”, says Giles, “saw a vision of a yellow serpent which descended from heaven, and laid its head on the slope of a mountain. The duke spoke of this to his astrologer, who said, ‘It is a manifestation of God; sacrifice to it’. In 747 B.C. another duke found on a mountain a being in the semblance of a stone. Sacrifices were at once offered, and the stone was deified and received regular worship from that time forward.”32

Giles states further in connection with Chinese god-stones: “Under 532 B.C. we have the record of a stone speaking.” The Marquis Lu inquired of his chief musician if this was a fact, and received the following answer: “Stones cannot speak. Perhaps this one was possessed by a spirit. If not, the people must have heard wrong. And yet it is said that when things are done out of season and discontents and complaints are stirring among the people, then speechless things do speak.”33

Precious stones were, like boulders or mountains, linked with the Great Mother. In Egypt the red jaspar amulet, called “the girdle of Isis”, was supposed to be a precious drop of the life-blood of that goddess. Herbs were connected with precious stones, and were credited with the attributes and characteristics of these stones. There are many references in Chinese, Indian, and other texts and folk-lores to gems that gleam in darkness. No gems do. The mandrake was similarly believed to shine at night. Both gem and herb were associated with the moon, a form of the mother-goddess, and were supposed to give forth light like the moon,34 just as stones associated with the rain-mother were supposed to become moist, or to send forth a stream of water, or to shed tears like the “weeping trees”, and like the sky from which drop rain and dew. The attributes of the goddess were shared by her “avatars”.

The amount or strength of the “soul-substance” in trees, herbs, well-water, stones, and animals varied greatly. Some elixirs derived from one or other of these “avatars” might prolong life by a few years; other elixirs might ensure many years of health.

The difference between a medicinal herb and the herb of immortality was one of degree in potency. The former was imbued with sufficient “soul-substance” to cure a patient suffering from a disease, or to give good health for months, or even years; the latter gave extremely good health, and those who partook of it lived for long periods in the Otherworld.

Even the “spiritual beings” (ling) of China were graded. The four ling, as De Visser states, are “the unicorn, the phœnix, the tortoise, and the dragon”. The dragon is credited with being possessed of “most ling of all creatures”.35

Stones were likewise graded. Precious stones had more ling than ordinary stones. Precious stones are sometimes referred to as pi-si. One Chinese writer says that “the best pi-si are deep-red in colour; that those in which purple, yellow, and green are combined, and the white ones take the second place; while those half white and half black are of the third grade”.36

Stones that displayed five colours combined apparently all the virtues of the five deities—the gods of the four quarters, and the sun, their chief. These were all children of the sixth deity, the Great Mother, who was the water on earth and the water above the firmament and the moon. The moon contained, as has been said, the “Pot” of fertilizing water which created all the water that flows into the Earth “Pot”. In China, as in Egypt and Western Europe, the Great Mother was the reproductive principle in Nature, the source of the moisture of life, the blood which is life, the sap of trees, the soul-substance in herbs, in fruit, in pearls, and in precious stones and precious metals—precious because of their close association with her.

It was the human dread of death and pain, the human desire for health and long life, and for the renewal of youth that instigated early man to search for the well of life, the plant of life, the curative herb, the pearl, and precious stones and precious metals. But before the search began, the complex ideas about the origin of life and the means by which it might be prolonged, which are reviewed in this chapter, passed through a long process of development in the most ancient centres of civilization. In China we meet not only with primitive ideas regarding life-giving food and water, but with ideas that had gradually developed for centuries outside China after the earliest attempts had been made to reanimate the corpse, not merely by painting it, but by preventing the body from decaying. In the history of mummification in Egypt may be found the history of complex beliefs that travelled far and wide.37 Even those peoples who did not adopt, or, at any rate, perpetuate the custom of mummification, adopted the belief that it was necessary to preserve the corpse. This belief is still prevalent in China, as will be shown, but magic takes the place of surgery.

In the next chapter evidence will be provided to indicate how the overland “drift” of culture towards China was impelled by the forces at work in Babylonia and Egypt.