CHAPTER XII

HOW COPPER-CULTURE REACHED CHINA

Metals connected with Deities—Introduction of Copper—Struggles for the First “Mine-Land”—Early Metal-working in Caucasus, Armenia, and Persia—Civilizations of Trans-Caspian Oases—Babylonian Influence in Mid Asia—Bronze and Jade carried into Europe—Ancient “Gold Rushes” to Siberia—Discoveries in Chinese Turkestan—Jade carried to Babylonia—Links between China, Iran, and Siberia—Bronze-links between China and Europe—Evidence of Ornaments and Myths—Early Metal-working—Far Eastern and European Furnaces Identical—Chinese Civilization dates from 1700 B.C.—Culture-mixing in Ancient Times.

The persistent and enterprising search for wealth in ancient times, which, as will be shown in this chapter, had so much to do with the spread of civilization, may seem quite a natural thing to modern man. But it is really as remarkable, when we consider the circumstances, to find the early peoples possessed of the greed of gold as it would be to find hungry men who have been ship-wrecked on a lonely island more concerned about its mineral resources than the food and water they were absolutely in need of. What was the good of gold in an ancient civilization that had no coinage? What attraction could it possibly hold for desert nomads?

The value attached to gold, which is a comparatively useless metal, has always been a fictitious value. As we have seen, it became precious in ancient times, not because of its purchasing power, but for the reason that it had religious associations. The early peoples regarded the precious metal as an “avatar” of the life-giving and life-sustaining Great Mother goddess—the “Golden Hathor”, the “Golden Aphrodite”.

In Egypt, Babylonia, Greece, India, and China the cow- and sky-goddess, the source of fertilizing water, was, in the literal sense, a goddess of gold. In India one of the five Sanskrit names for gold is Chandra1 (“the moon”), and the Indus was called “Golden Stream”, not merely because gold was found in its sand, but because of its connection with the celestials. “Gold is the object of the wishes of the Vedic singer, and golden treasures are mentioned as given by patrons, along with cows and horses. Gold was used for ornaments for neck and breast, for ear-rings, and even for cups. Gold is always associated with the gods. All that is connected with them is of gold; the horses of the sun are ‘gold skinned’, and so on.” This summary by two distinguished Sanskrit scholars emphasizes the close connection that existed in India between gold and gold ornaments and religious beliefs.2

“Gold”, a reader may contend, “is, of course, a beautiful metal, and the ancients may well have been attracted by its beauty when they began to utilize it for ornaments.” But is there any proof that ornaments were adopted, because, in the first place, they made appeal to the æsthetic sense, which, after all, is a cultivated sense, and not to be entirely divorced from certain mental leanings produced by the experiences and customs of many generations? Do ornaments really beautify those who wear them? Was it the æsthetic sense that prompted the early peoples to pierce their noses and ears; and to extend the lobes of their ears so as to “adorn” themselves with shells, stones, and pieces of metal? Can we divorce the practice of mutilation from its association with crude religious beliefs? Inherited ideas of beauty may be wrong ideas, and it can be said of the modern lady who wears collections of brilliant and costly jewels that she is not necessarily made more beautiful by perpetuating a custom rooted in the grossest superstitions of antiquity, for these jewels were originally charms to preserve health, to regulate the flow of blood, to promote fertility and birth, and, generally speaking, to secure “luck” by bringing the wearer into close touch with the “deities”, whose “soul-substance” was contained in them.

When the æsthetic sense of mankind reached that high stage of development represented by Greek sculpture, the so-called ornaments were discarded and the human form depicted in all its natural beauty and charm.

Whatever was holy seemed beautiful to the early people, and that is why in a country like India, with its wealth of exquisitely coloured flowers, the Sanskrit names for gold include Jāta-rūpa (native beauty), and Su-varna (good, or beautiful colour). The gold colour was really a luck-bringing colour, and therefore beautiful to Aryan eyes.

Having attached in their homelands a fictitious religious value to gold, the early prospectors and miners carried their beliefs and customs with them wherever they went, and these were in time adopted by the peoples with whom they came into contact.

When Columbus crossed the Atlantic he and his followers greatly astonished the unsophisticated natives of the New World by their anxiety to obtain precious metals. They found, to their joy, that “the sands of the mountain streams glittered with particles of gold; these”, as Washington Irving says,3 “the natives would skilfully separate and give to the Spaniards, without expecting a recompense”.

No doubt the early searchers for gold in Africa and Asia met with many peoples who were as much amused and interested, and as helpful, as were the natives of the New World, who welcomed the Spaniards as visitors from the sky.

Gold was the earliest metal worked by man. It was first used in Egypt to fashion imitation sea-shells, and the magical and religious value attached to the shells was transferred to the gold which, in consequence, became “precious” or “holy”.

Copper was the next metal to be worked. It was similarly used for the manufacture of personal ornaments and other sacred objects, being regarded apparently, to begin with, as a variety of gold. But in time—some centuries, it would appear, after copper was first extracted from malachite—some pioneer of a new era began to utilize it as a substitute for flint, and copper knives and other implements were introduced. This discovery of the usefulness of copper had far-reaching effects, and greatly increased the demand for the magical metal. Increasing numbers of miners were employed, and search was made for new copper-mines by enterprising prospectors who, in Egypt, were employed, or, at any rate, protected, by the State. This search had much to do with promoting race movements, and introducing not only new modes of life but new modes of thought into lands situated at great distances from the areas in which these modes of life and thought had origin. The metal-workers were the missionaries of a New Age. In this chapter it will be shown how they reached China.

Archæologists are not agreed as to where copper was first used for the manufacture of weapons and implements. Some favour Egypt, and others Mesopotamia. In the former country the useful metal was worked in pre-Dynastic times, that is, before 3500 B.C. or 4500 B.C. “Copper ornaments and objects, found in graves earlier than the middle pre-Dynastic period”, wrote the late Mr. Leonard W. King, “are small and of little practical utility as compared with the beautifully flaked flint knives, daggers, and lances.… At a rather later stage in the pre-Dynastic period, copper dagger-blades and adzes were produced in imitation of flint and stone forms, and these mark the transition to the heavy weapons and tools of copper which, in the early Dynastic period, largely ousted flint and stone implements for practical use. The gradual attainment of skill in the working of copper ore on the part of the early Egyptians had a marked effect on the whole status of their culture. Their improved weapons enabled them by conquest to draw their raw materials from a far more extended area.”4

Copper was found in the wadis of Upper Egypt and on the Red Sea coast—in those very areas in which gold was worked for generations before copper was extracted from malachite. At a later period the Pharaohs sent gangs of miners to work the copper-mines in the Sinaitic peninsula. King Semerket, of the early Dynastic age, had men extracting copper in the Wadi Maghara. “His expedition was exposed to the depredations of the wild tribes of Beduin … and he recorded his punishment of them in a relief on the rocks of the Wadi.” There is evidence that at this remote period the Pharaohs “maintained foreign relations with far remote peoples”.5 A record of a later age (c. 2000 B.C.) affords us a vivid glimpse of life in the “Mine-Land”. An official recorded in an inscription that he had been sent there in what he calls the “Evil summer season”. He complained, “It is not the season for going to this Mine-Land.… The highlands are hot in summer, and the mountains brand the skin.” Yet he could boast that “he extracted more copper than he had been ordered to obtain”.6

The transition from stone to copper cannot be traced in ancient Babylonia. Sumerian history begins at the seaport Eridu, when that centre of civilization was situated at the head of the Persian Gulf—a fact that suggests the settlement there of seafaring colonists. At the dawn of Sumerian culture, copper tools and weapons had come into use. No metals could be found in the alluvial “plain of Shinar”.

The early Babylonians (Sumerians) had to obtain their supplies of copper from Sinai, Armenia, the Caucasus area, and Persia. It may be that their earliest supplies came from Sinai, and that the battles in that “Mine-Land”, recorded in early Egyptian inscriptions, were fought between rival claimants of the ore from the Nile valley and the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates. One ancient Pharaoh refers in an inscription to his “first occurrence of smiting the Easterners” in Sinai. “This designation”, comments Breasted, “of the event as the ‘first occurrence’ would indicate that it was a customary thing for the kings of the time (First Dynasty, c. 3500 B.C.) to chastise the barbarians.”7 But were they really “barbarians”? Is it likely that barbarians would be found in such a region, especially in summer? It is more probable that the “Easterners” came from an area in which the demand for copper was as great as it was in Egypt.

The regular battles between the ancient “peggers-out” of “claims” in Mine-Land no doubt forced the “Easterners” to search for copper elsewhere. By following the course of the Tigris the Sumerian prospectors were led to the rich mineral area of the Armenian Highlands, and it is of special significance in this connection to find that the earliest Assyrian colonies were founded by Sumerians. Apparently Nineveh (Mosul) had origin as a trading centre at which metal ores were collected and sent southward some time before the Semitic Akkadians obtained control of the northern part of the Babylonian plain.

The copper obtained from Armenia and other western Asiatic areas was less suitable than Sinaitic copper, being much softer. Sinaitic and Egyptian copper is naturally hard on account of the proportion of sulphur it contains. But after tin was found, and it was discovered that, when mixed with copper, it produced the hard amalgam known as bronze, the Sumerians appear to have entirely deserted the Sinaitic Mine-Land, and left it to the Egyptians.

The Egyptians continued in their Copper Age until their civilization ceased to be controlled by native kings.

Babylonia had likewise a Copper Age to begin with, but copper was at an early period entirely supplanted by bronze, except for religious purposes—a fact which is of great importance, especially when it is found that the religious beliefs associated with copper and gold were disseminated far and wide by the early miners—the troglodytes of Sinai in the early Egyptian texts—who formed colonies that became industrial and trading centres. Votive images found in Babylonia are of copper. A good example of early Sumerian religious objects is the interesting bull’s head in copper from Tello, which is dated c. 3000 B.C. The eyes of this image of the bull-god— the “Bull of Heaven”, the sky-god, whose mother or spouse was the “Cow of Heaven”—“are inlaid with mother-of-pearl and lapis-lazuli”. A “very similar method is met with in the copper head of a goat which was found at Fara”.8 Here we find fused in early Sumerian religious objects complex religious beliefs connected with domesticated animals, sea-shells, and metals.

The opinion, suggested here by the writer, that the battles between rival miners in Sinai compelled the Sumerians to search for copper elsewhere and to discover means whereby the softer copper could be hardened, appears to accord with the view that bronze was first manufactured in Babylonia, or in some area colonized by Babylonia. In his able summary of the archæological evidence regarding the introduction of bronze, Sir Hercules Read shows that “the attribution of the discovery to Babylonia is preferred as offering fewest difficulties”.9

Recent archæological finds make out a good case for Russian Turkestan as the “cradle of the bronze industry”.

In Troy and Crete bronze supplanted flint and obsidian. There was no Copper Age in either of these culture centres. The copper artifacts found in Crete are simply small and useless votive axes and other religious objects.

Whence did the Babylonians receive, after the discovery was made how to manufacture bronze, the necessary supplies of tin? Armenia and the Caucasus “appear”, as Read says, “to be devoid of stanniferous ores”. Apparently the early metal-searchers had gone as far as Khorassan in Persia before their fellows had ceased to wage battles with Egyptians in the Sinaitic “Mine-Land”. Tin has been located at Khorassan and “in other parts of Persia, near Asterabad and Tabriz.10… From such areas as these”, Reid says, “the tin used in casting the earliest bronze may have been derived.” We are now fairly on our way along the highway leading to China. “In Eastern Asia, beyond the radius of the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia”, Read continues, “there would seem to be no region likely to have witnessed the discovery (of how to work bronze) nearer than Southern China; for India, which has copper implements of a very primitive type, is poor in tin … while the Malay peninsula, an extremely rich stanniferous region, does not appear to have been mined in very ancient times”.11 It is unlikely that bronze was first manufactured in China, considering the period of its introduction into Babylonia, which antedates by several centuries the earliest traces of civilization in the Far East.

The history of the development of the industries and commerce of early Babylonia is the history of the growth and dissemination of civilization, not only in western Asia, but in the “Mid East” and the “Far East”.

Babylonia, the Asiatic granary of the ancient world, lay across the trade routes. Both its situation and its agricultural resources gave it great commercial importance. It had abundant supplies of surplus food to stimulate trade, and its industrial activity created a demand for materials that could not be obtained in the rich alluvial plain. “Over the Persian Gulf”, says Professor Goodspeed,12 “teak-wood, found in Eridu (the seaside “cradle” of Sumerian culture), was brought from India. Cotton also made its way from the same source to the southern cities. Over Arabia, by way of Ur, which stood at the foot of a natural opening from the desert … were led the caravans laden with stone, spices, copper, and gold13 from Sinai, Yemen, and Egypt. Door-sockets of Sinaitic stone found at Nippur attest this traffic.” Cedar wood was imported from the Syrian mountains “for the adornment of palaces and temples. From the east, down the pass of Holwan, came the marble and precious metal of the mountains. Much of this raw material was worked over by Babylonian artisans and shipped back to less-favoured lands, along with the grain, dates, and fish, the rugs and cloths of native production. All this traffic was in the hands of Babylonian traders, who fearlessly ventured into the borders of distant countries, and must have carried with them thither the knowledge of the civilization and wealth of their own home, for only thus can the widespread influence of Babylonian culture in the earliest periods be explained.”

It was evidently due to the influence of the searchers for metals and the traders that the culture of early Sumeria spread across the Iranian plateau. As Laufer has shown,14 “the Iranians were the great mediators between the West and the East”. The Chinese “were positive utilitarians, and always interested in matters of reality; they have bequeathed to us a great amount of useful information on Iranian plants, products, animals, minerals, customs, and institutions”. Not only plants but also Western ideas were conveyed to China by the Iranians.15

The discoveries of archæological relics made by the De Morgan Expedition in Elam (western Persia), and by the Pumpelly Expedition in Russian Turkestan, have provided further evidence that Sumero-Babylonian civilization exercised great influence over wide areas in ancient times. Unfortunately no such records as those made by the Egyptians who visited Mine-Land have been discovered either in Babylonia or beside the mineral workings exploited by the Sumerians or Akkadians. The Egyptian Pharaohs, as we have seen, had to send military forces to protect their miners, and on one occasion found it necessary to conduct mining operations in the hot season instead of in the cool season, a fact which suggests that the opposition shown by rivals was at times very formidable. It does not follow that the Babylonians had to contend with similar opposition in Armenia and Persia. They appear to have won the co-operation of the native peoples in the mid-Asian mining districts, and to have made it worth their while to keep up the supply of gold, and copper, and tin. Babylonia had corn and manufactured articles to sell, and they made it possible for native chiefs to organize their countries and to acquire wealth and a degree of luxury. Nomadic pastoral peoples became traders, and communities of them adopted Babylonian modes of life. Mr. W. J. Perry has shown that in districts where minerals were anciently worked, the system of irrigation, which brought wealth and comfort in Babylonia and the Nile valley, was adopted, and that megalithic monuments were erected.16

The early searchers for metals and pearls and precious stones were apparently the pioneers of civilization in many a district occupied by backward peoples.

The mineral area to the south-east of the Caspian Sea appears to have been exploited as early as the third millennium B.C., as was also the mineral area stretching from the Caspian to the eastern coast of the Black Sea. New trade routes were opened up and connections established, not only with Elam and Babylonia in the south, but with Egypt, through Palestine, and with Crete and with the whole Ægean area. Troy became the “clearing-house” of this early trade flowing from western Asia into Europe. The enterprising sea-kings of Crete appear to have penetrated the Dardanelles and reached the eastern shores of the Black Sea, where they tapped the overland trade routes.17 Dr. Hubert Schmidt, who accompanied the Pumpelly expedition to Russian Turkestan in 1903–4, found Cretan Vasiliki pottery in one of the excavated mounds, and, in another, “three-sided seal-stones of Middle Minoan type (c. 2000 B.C.), engraved with Minoan designs”.18 There is evidence which suggests that this trade in metals between western Asia and the Ægean area was in existence long before 2500 B.C., and not long after 3000 B.C.

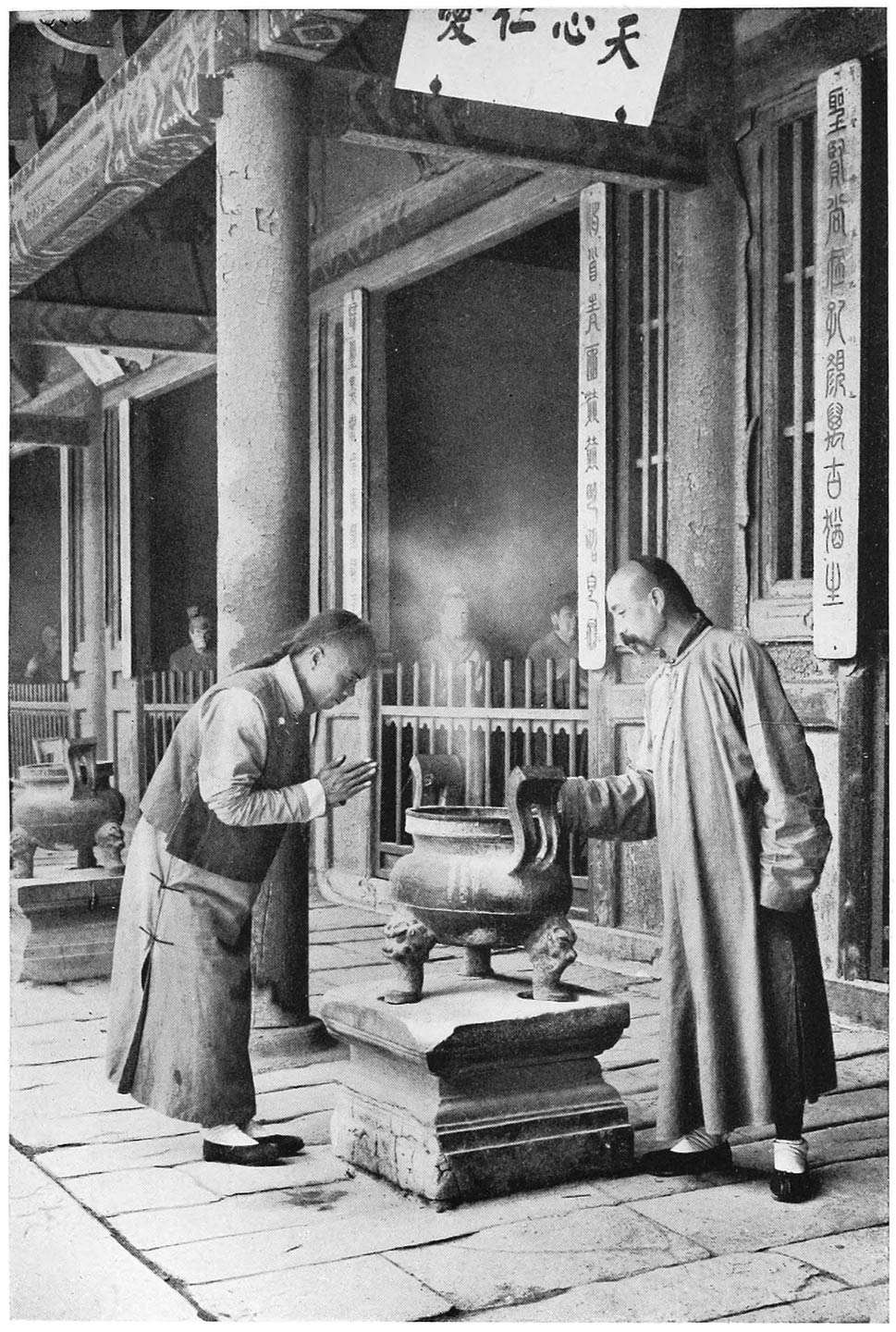

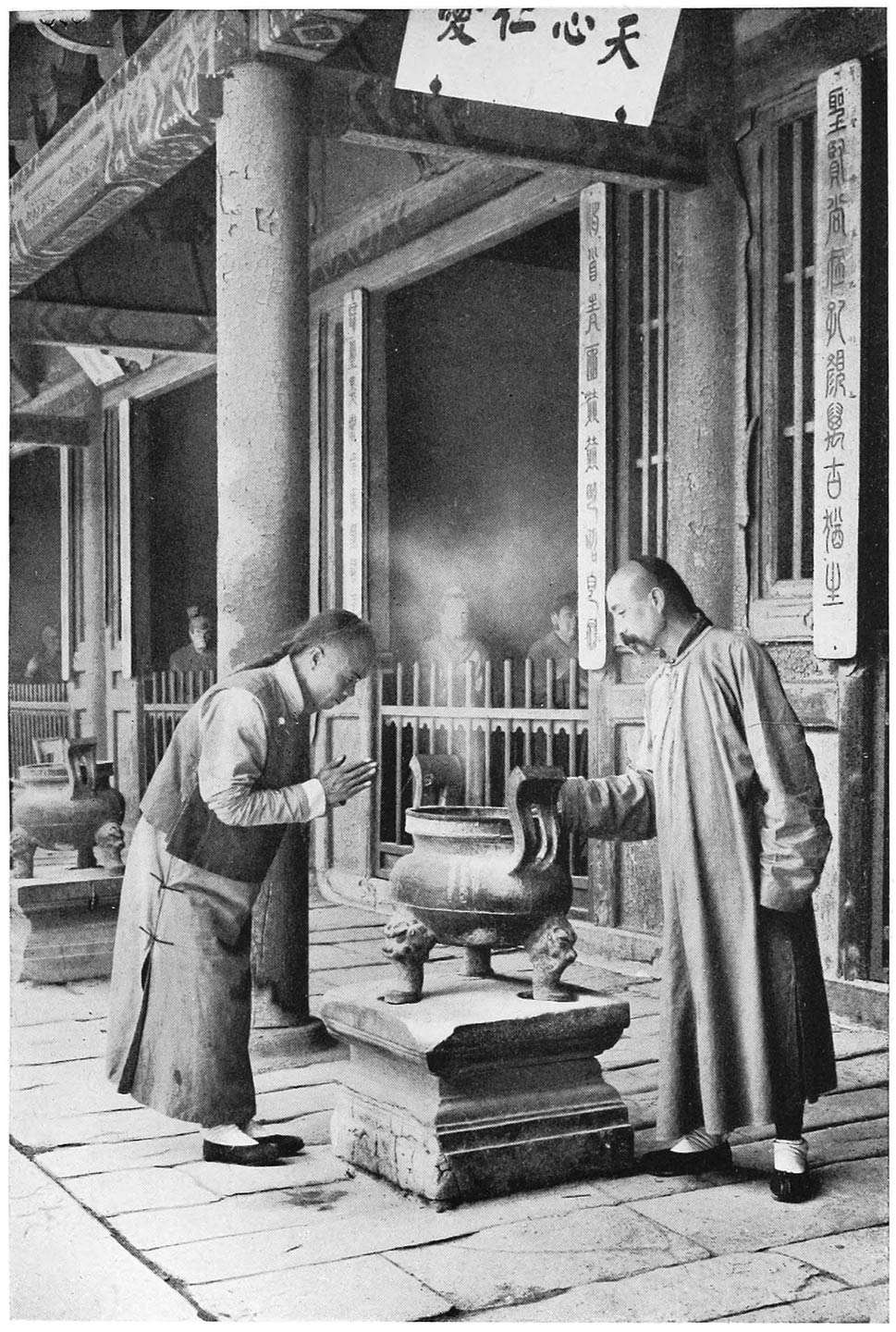

Copyright H. G. Ponting. F.R.G.S.

AN OFFERING TO THE GODS, PEKING

One of the great centres of Mesopotamian culture in the south-eastern Caspian area was Anau, near Askabad, on the Merve-Caspian railway route. Another was Meshed, which lies to the south-east of Anau in a rich metalliferous mountain region. One of the “Kurgans” (mounds) excavated at Anau yielded archæological relics that indicated an early connection between Turkestan and Elam in south-western Persia. In another “Kurgan” were found traces of a copper-culture. The early searchers for metals were evidently the originators or introducers of this culture, and as the stratum contained baked clay figurines of the Sumerian mother-goddess, the prototype of Ishtar, little doubt can remain whence came the earliest miners. This region of desolate sand-dunes was in ancient times irrigated by the Mesopotamian colonists who sowed not only the seeds of barley, wheat, and millet, but also the seeds of civilization, and stimulated progress among the native tribes. The settlers built houses of bricks which had been sun-dried in accordance with the prevailing Babylonian fashion. The Egyptian potter’s wheel was introduced—another indication that regular trading relations between Babylonia and Egypt were maintained at a very early period.

Mr. Pumpelly, in the first flush of enthusiasm aroused by the mid-Asia revelations, urged the claim that the agricultural mode of life originated in the Transcaspian Oases, and that it passed thence to Babylonia and Egypt. But the discovery of husks of barley in the stomachs of naturally mummified bodies found in the hot dry sands of Upper Egypt affords proof that cannot be overlooked in this connection.19 Agriculture was practised in the Nile valley long centuries before the Transcaspian Copper Age was inaugurated. Besides, barley and millet grow wild in the Delta area.

The early Mesopotamian searchers for metals, and their pupils from the Transcaspian region, continued the explorations towards the east. They appear to have wandered to the north-west of the Oxus and the south-east of the Lake Balkash and apparently to the very borders of China. This eastward drift must have been in progress long before the introduction of bronze into central Europe, which had a Stone Age culture for three or four centuries after bronze implements had become common in Troy and Crete. The traders who carried bronze into Hungary carried jade too, and the beliefs which had been connected with jade in Asia. The earliest supplies of European jade objects must have come, as will be shown, from Chinese Turkestan.

There was good reason for the early gold rush towards the east. Gold can still be easily found “everywhere and in every form” in Siberia. The Altai means “gold mountains”, and these yield silver and copper as well as gold. Indeed, eastern Siberia is a much richer metalliferous area than western Siberia, and this fact appears to have been ascertained at a very remote period. The searchers for metals not only collected gold, copper, and silver on the Altai Mountains and the area of the upper reaches of the Yenesei River, but also penetrated into Chinese Turkestan, where, as in Russian Turkestan, trading colonies were founded, the metals were worked, and the agricultural mode of life, including the system of irrigation, adopted with undoubted success.20 Important archæological excavations, conducted by Dr. Stein in Chinese Turkestan, “on behalf of the Indian Government”, have revealed traces of the far-reaching influences exercised by Mesopotamian culture in a region now covered by the vast and confusing sand-dunes of the Taklamakan Desert. At Khotan the discoveries made were of similar character to those at Anau.

Khotan is the ancient trading centre which connected central Asia and India, and India and China. One of the most important products of Khotan is jade—that is, important from the historical point of view. It is uncertain at what period the importation of jade into China from the Khotan area was inaugurated. But there can be no doubt about the antiquity of the jade trade between Chinese Turkestan and Babylonia. Some of the Babylonian cylinder-seals were of jade, others being of “marble, jasper, rock-crystal, emerald, amethyst, topaz, chalcedony, onyx, agate, lapis-lazuli, hæmatite, and steatite”21—all relics of ancient trade and mining activity. Turquoise was imported into Babylonia from Khotan and Kashgar. The archæological finds made on the site of the ancient Sumerian city at Nippur include cobalt, “presumably from China”.22 At Nippur was found, too, Persian marble, lapis-lazuli from Bactria, and cedar and cypress from Zagros.

When it is borne in mind that the chief incentive behind the search for precious metals and precious stones was a religious one, we should not express surprise to find that not only the products of centres of ancient civilization were carried across Asia to outlying parts, but also myths, legends, and religious beliefs of complex character. These were given a local colouring in different areas. In northern Siberia, for instance, the local fauna displaced the fauna of the southern religious cults, the reindeer or the goat taking the place of the gazelle or the antelope. Mythological monsters received new parts, just as the dolphin-god of Cretan and other seafaring peoples received an elephant’s head in northern India and became the makara; and the seafarers’ shark-god received in China the head of a lion, although the lion is not found in China. No doubt the lion was introduced into China as a religious art motif by some intruding cult. Touching on this phase of the problem of early cultural contact, Ellis H. Minns23 suggests a number of possibilities to account for the similarities between Siberian and Chinese art. One is that “the resemblance may be due to both (Siberians and Chinese) having borrowed from Iranian or some other Central Asian art.… In each case,” he adds, “we seem to have an intrusion of monsters ultimately derived from Mesopotamia, the great breeding-ground of monsters.” The data summarized in a previous chapter24 dealing with the Chinese dragon affords confirmation of this view.

Dr. Joseph Edkins, writing in the seventies of last century as a Christian missionary who made an intensive study of Chinese religious beliefs at first hand, had much to say about the “grafting process” or culture-mixing. “Every impartial investigator”, he wrote, “will probably admit that the ceremonies and ideas of the Chinese sacrifices link them with Western antiquity. The inference to be drawn is this, that the Chinese primeval religion was of common origin with the religions of the West. But if the religion was one, then the political ideas, the mental habits, the sociology, the early arts and knowledge of nature, should have been of common origin also with those of the West.”25

No doubt the stories brought from Siberia by the early explorers tended to stimulate the imaginations of the myth-makers of Mesopotamia, India, and China. The mineral and hot springs in the cold regions may have been regarded as proof that “the wells of life” had real existence. Some of these wells are so greatly saturated with carbonic acid gas that they burst skin and stone bottles. “Here is living water indeed!” the early explorer may have exclaimed when he attempted to carry away a sample. “The feathers in the air”, as Herodotus puts it when referring to the snow, and the aurora borealis must have greatly impressed the early miners in the mysterious Altai region—a region possessing so much mineral wealth that it must have been regarded as a veritable wonderland of the gods by the early prospectors. Who knows but that the story of Gilgamesh’s pilgrimage through the dark mountain to the land in which trees bore gems instead of fruit owes something to the narratives of the early explorers who reached mysterious regions rich in metals and gems, where the strange murmurings that fill the air on still winter nights are still referred to as “the whisperings of the stars”, and the aurora borealis, which scatters the darkness and illumines snow-clad mountain ranges and valleys, displays wonderful and vivid colours in great variety.

That the early culture which was disseminated eastward across Siberia to China and westward into Europe was of common origin, is clearly indicated by the archæological remains.

Dealing with the bronzes of Russia and Siberia, Sir Hercules Read writes: “At both extremities of the vast area stretching from Lake Baikal through the Southern Siberian Steppes across the Ural Mountains to the basin of the Volga, and even beyond to the valleys of the Don and Dnieper, there have been found, generally in tombs, but occasionally on the surface of the ground, implements and weapons marked by the same peculiarities of form, and by a single style of decoration. These objects exhibit an undoubted affinity with those discovered in China; but some of the distinctive features have been traced in the bronze industry of Hungary and the Caucasus; for example, pierced axes and sickles have a close resemblance to Hungarian and Caucasian forms. The Siberian bronzes have this relationship both in the East and West, but their kinship with Chinese antiquities being the more obvious, it is natural to assume that the culture which they represent is of East Asiatic origin.” Read notes, however, that “most of the Chinese bronze implements are of developed, and therefore not of primitive forms.… Such forms can only have been reached after a long period of evolution, but their prototypes are found neither in the Ural-Altaic region itself, where some objects may indeed be simpler in design than others, but cannot be described as quite primitive; nor as yet within the limits of China.”26

The evidence afforded by ancient religious beliefs and customs tends to show that the cultural centre in Asia, which stimulated the growth of civilization, was Babylonia, while Egyptian influence flowed northward through Palestine and into Syria. In time the influence of Cretan civilization made itself felt on the eastern shores of the Black Sea. The ebb and flow of cultural influences along the trade routes at various periods renders the problem of highly complex character. But one leading fact appears to emerge. The demand for metals and precious stones in the earliest seats of civilization—that is, in Babylonia and Egypt—stimulated exploration and the spread of a culture based on the agricultural mode of life. Not only was the system of irrigation, first introduced in the Nilotic and Tigro-Euphratean valleys, adopted by colonies of miners and traders who settled in mid-Asia and founded sub-cultural centres that radiated westward and eastward; the religious ideas and customs that had grown up with the agricultural mode of life in the cradles of ancient civilization were adopted too. New experiences and new inventions imparted “local colour” to colonial culture, but the leading religious principles that veined that culture underwent little change. The immemorial quest for the elixir of life was never forgotten. It was not to purchase their daily bread alone that men lived laborious days washing gold dust from river sands, crushing quartz among the Altai Mountains, or quarrying and fishing jade in Chinese Turkestan; they were chiefly concerned about “purchasing” the “food of life” so as to secure immortality. The fear of death, which sent Gilgamesh on his long journey, caused many a man in ancient times to wander far and wide in search of life-giving metals, precious stones, pearls, and plants. And so we find in China as in Egypt, in Babylonia as in western Europe, that the quest of immortality was the chief incentive that stimulated research, discovery, and the spread of civilization. The demand for the wood of sacred trees, incense-bearing trees and plants, precious metals and precious stones in the temples of Egypt and Babylonia, had much to do with the development of early trade. The Pharaohs of Egypt and the Patesies of Sumeria fitted out expeditions to obtain treasure for their holy places, and to keep open the trade routes along which the treasure was carried.

That the system of metal-working had anciently an area of origin is emphasized by the investigations conducted by Professor Gowland.27 He deals first with the Japanese evidence. “The method which was practised, and the furnace employed by the early workers, still”, he writes, “survive in use at several mines in Japan at the present time.” A hole in the ground forms the furnace, and a bellows is used to introduce the blast from the top. After the copper is smelted it is allowed to cool off, and when it is nearly solidified it is taken out and broken up. “The copper thus produced in Japan is never cast direct from the smelting furnaces into useful forms, but is always resmelted in crucibles, a mode of procedure which undoubtedly prevailed in Europe during the early Metal and the Bronze Ages.” The Japanese clay crucibles “are analogous to those found in the pile-dwellings of the Swiss and Upper Austrian lakes”.

Dealing with iron-furnaces, the Professor shows that the Ancient Egyptian furnace resembled “the Japanese furnace for copper, tin, and lead”. The Etruscan furnace also resembled the Egyptian one. “From metallurgical considerations only”, Gowland adds, “we would certainly be led to the inference that the Etruscans had obtained their knowledge of the method of extracting metal from that (the Egyptian) source.” British evidence suggests that the methods obtaining in ancient times were introduced from “the Mediterranean region of Europe.… The actual process for the extraction of iron from its ores in Europe, in fact in all countries in early times, was practically the same.”

Elsewhere, Professor Gowland has written: “It is important to note … that the type of furnace which survives in India among the hill tribes of the Ghats is closely analogous to the prehistoric furnace of the Danube, and of the Jura district in Europe”.28

“Culture-drifts” can thus be followed in their results. Backward communities that adopted inventions in early times continue to use them in precisely the same manner as did those ancient peoples by whom they were first introduced. In like manner are early beliefs and customs still perpetuated in isolated areas. But it does not follow that all these beliefs had origin among the peoples who still cling to them. Some so-called “primitive” beliefs are really of highly complex character, with as long a history of development as has the primitive type of furnace utilized by the hill tribes of India.

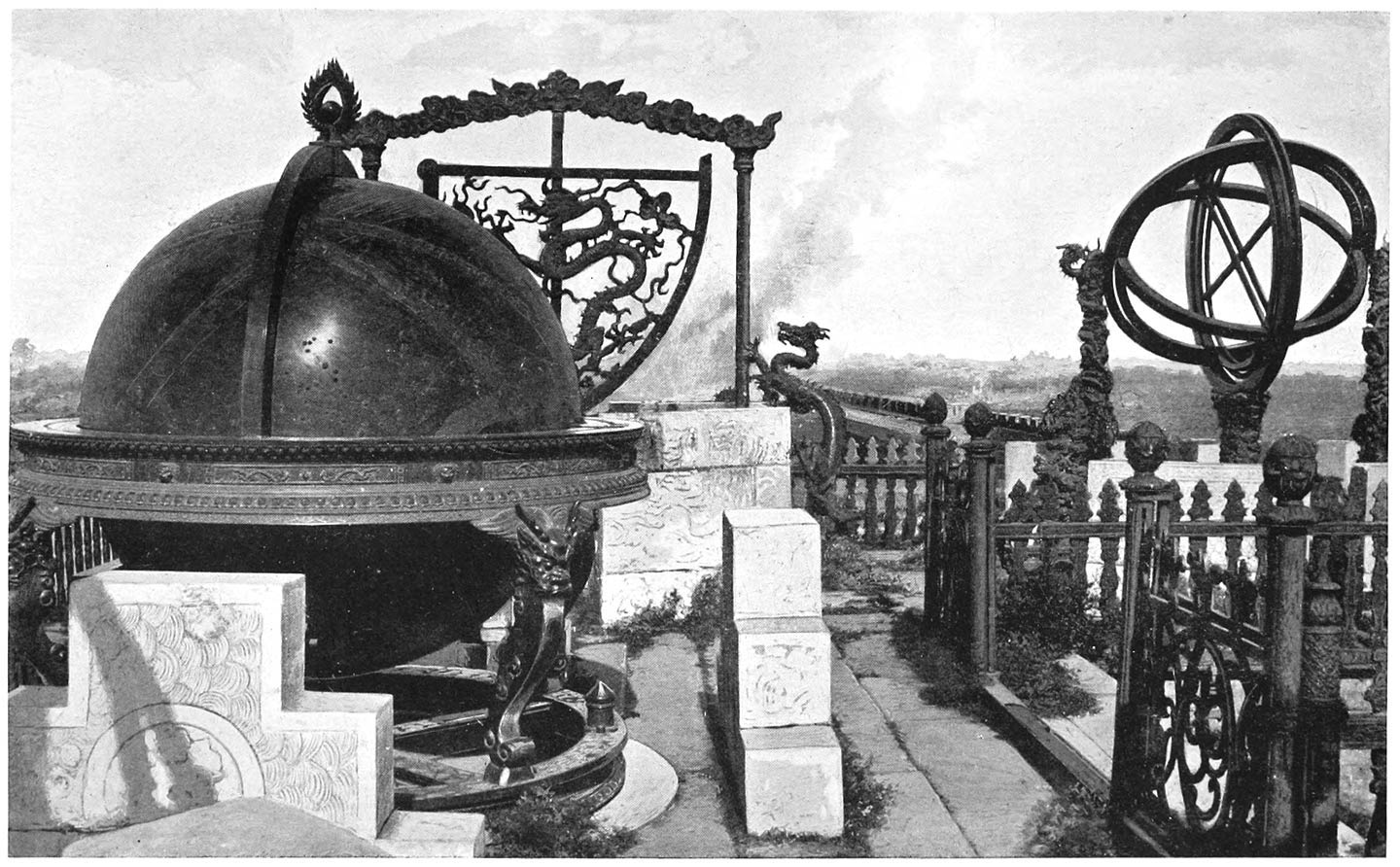

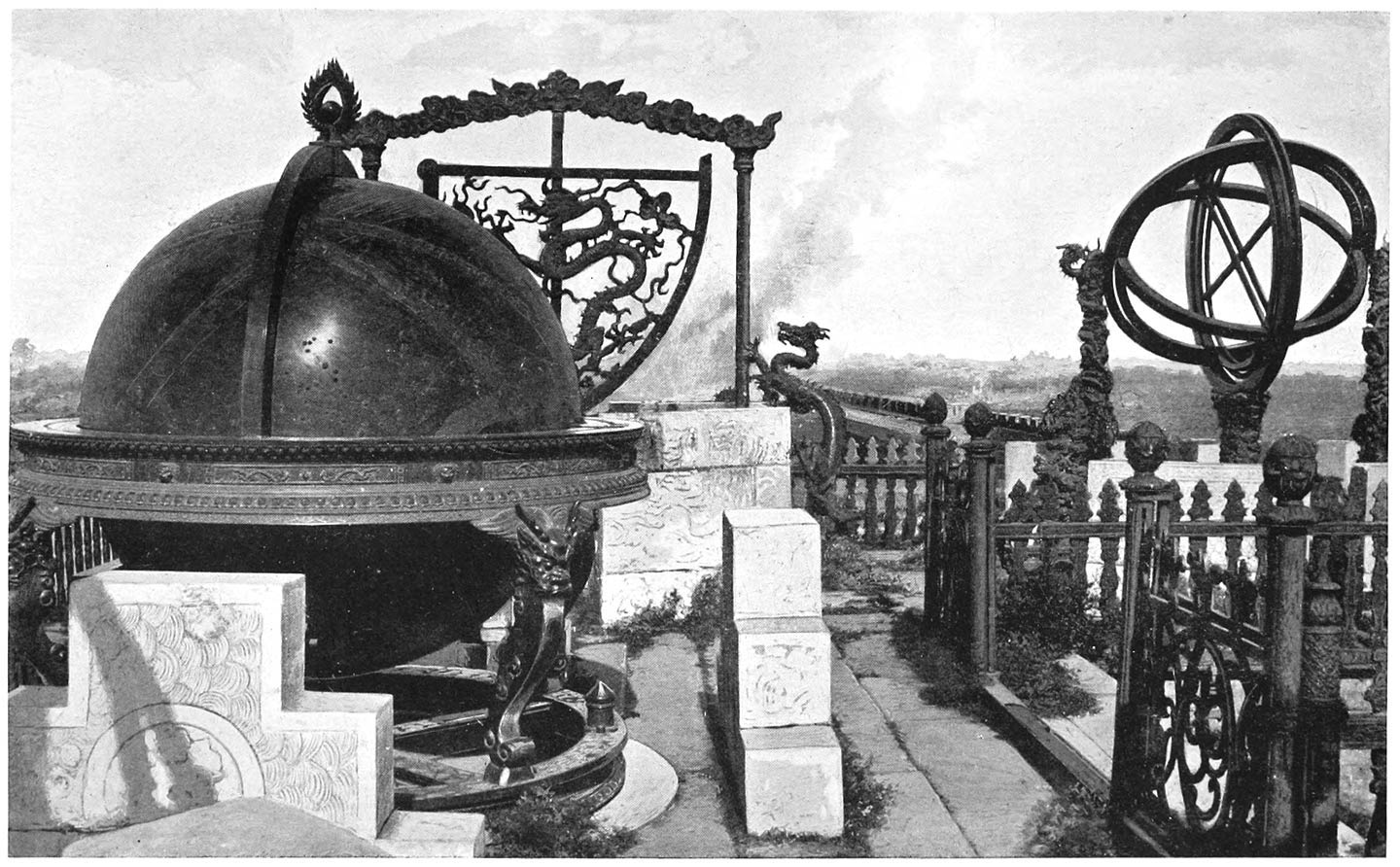

ANCIENT BRONZE ASTRONOMICAL INSTRUMENTS ON THE CITY WALL, PEKING

In the next chapter it will be shown that in the jade beliefs of China traces survive of ideas not necessarily of Chinese origin—ideas that, in fact, grew up and passed through processes of development in countries in which jade was never found. For, as the Chinese bronze implements are “not of primitive forms”, and therefore not indigenous, neither are all Chinese beliefs and customs “primitive” in the same sense, or, in the real sense, indigenous either. As the stimulus to work metals in China came from an outside source, so, apparently, did the stimulus to search for such a “life-giving” and “luck-conferring” material as jade come from other countries, and from races unrelated to those that occupied China in early times.

The beliefs associated with jade were developed in China, although they did not originate there; and these beliefs were similar to those attached to the pearls, the precious stones, and the precious metals searched for by the ancient prospectors who discovered and first worked jade in Chinese Turkestan and on the borders of China.

To sum up, it would appear that the elements of a religious culture, closely associated with the agricultural mode of life, and common to Sumeria and Egypt, passed across Asia towards China, reaching the Shensi province about 1700 B.C. At a much later period the complex culture of the Egyptian Empire period gradually drifted along the sea route and left its impress on the Chinese coast. Iranian culture, which was impregnated with Babylonian and Egyptian ideas, likewise exercised a persisting influence, and was renewed again and again.

One of the ultimate results of the rise of Persia as a world-power, and of the invasion of Asia by Alexander, was to bring China into direct touch with the Hellenistic world.

Indian influence is represented chiefly by Buddhism. In northern India Buddhism had been blended with Naga (serpent) worship, and when it reached China, the local beliefs regarding dragons were given a Buddhistic colouring. The Chinese Buddhists mixed the newly-imported religious culture with their own. The “Islands of the Blest” were retained by the cult of the East, and the Western Paradise by the cult of the West. The latter paradise is unknown to the Buddhists in Burmah and Ceylon, but has never been forgotten by the Buddhists of northern China. A Buddha called “Boundless Age” was placed in the garden of the Royal Lady of the West, but that goddess still lingered beside the Peach Tree of Immortality, while the sky-goddess continued to weave the web of the constellations, and the pious men and women of the Taoist faith were supposed to reach her stellar Paradise by sailing along the Celestial River in dragon-boats or riding on the back of dragons. The Chinese Buddhists found ideas regarding Nirvana less satisfying than those associated with the Paradise of the “Peaceful Land of the West” and the higher Paradise of the “Palaces of the Stars”, in which dwelt the gods and the demi-gods of the older faiths.

Writing in this connection, Dr. Joseph Edkins says: “A mighty branch of foreign origin has been grafted in the old stock. The metaphysical religion of Shakyamuni was added to the moral doctrines of Confucius. Another process may then be witnessed. A native twig was grafted in the Indian branch. Modern Taoism has grown up on the model supplied by Buddhism. That it is possible to observe the modus operandi of this repeated grafting, and to estimate the amount of gain and loss to the people of China, resulting from the varied religious teaching which they have thus received, is a circumstance of the greatest interest to the investigator of the world’s religions.”29