however, the existence of the thinking human brain remains a miracle.

Friedrich Wöhler and Charles Darwin, adapted from Annenberg Rare

Book and Manuscript Library

[Origin of Life]

With these three great discoveries, the main processes of nature are ex-

plained and traced back to natural causes. Only one thing remains to to

done here: to explain the origin of life from inorganic nature. At the present

stage of science, that means nothing else than the preparation of albu-

minous bodies from inorganic materials. Chemistry is approaching ever

closer to this task. it is still a long way from it. But when we reflect that it

was only in 1828 that the first organic body, urea, was prepared by Wöh-

ler from inorganic materials and that innumerable so-called organic com-

pounds are now artificially prepared without any organic substances, we

shall not be inclined to bid chemistry halt before the production of albu-

men. Up to now, chemistry has been able to prepare any organic substance

the composition of which is accurately known. As soon as the composition

of albuminous bodies shall have become known, it will be possible to pro-

ceed to the production of live albumen. But that chemistry should achieve

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

317

Chapter 27. “Science of Natural Processes” by Frederick Engels

over night what nature herself even under very favorable circumstances

could succeed in doing on a few planets after millions of years—would be

to demand a miracle.

[Scientific Materialism]

The materialist conception of nature, therefore, stands today on very dif-

ferent and firmer foundations than in the last century. Then it was only

the motion of the heavenly bodies and of rigid terrestrial bodies under

the influence of gravity that was thoroughly understood to some extent.

Almost the whole sphere of chemistry and the whole of organic nature

remained an incomprehensible secret. Today, the whole of nature is laid

open before us as a system of interconnections and processes which have

been, at least in their main features, explained and comprehended. Indeed,

the materialistic outlook on nature means no more than simply conceiv-

ing nature just as it exists without any foreign admixture, and as such it

was understood originally among the Greek philosophers as a matter of

course. But between those old Greeks and us lie more than two thousand

yeas of an essentially idealistic world outlook and hence the return to the

self-evident is more difficult than it seems as first glance. For the question

is not at all one of simply repudiating the whole thought-content of those

two thousand years but of criticizing it in order to extricate from within

the false, but for its time and the process of evolution even inevitable, ide-

alistic form, the results gained from this transitory form. And how difficult

that is, is demonstrated for us by those numerous scientists who are inex-

orable materialists within their science but who, outside it, are not only

idealists but even pious, nay orthodox, Christians.

From Frederick Engels’ Anti-Dühring. . .

“All religion, however, is nothing but the fantastic reflection in men’s

minds of those external forces which control their daily life, a reflec-

tion in which the terrestrial forces assume the form of supernatural

forces.”

318

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 27. “Science of Natural Processes” by Frederick Engels

Related Ideas

Marxists Internet Archive (http://www.marxists.org/) . Marxist Writers

and History. Comprehensive reference and sources for the philosophy of

Marxism—useful for many online sources not available elsewhere.

Cosmology Today (http://www.flash.net/~csmith0/index.htm). A series of

accessible articles by scientists on the present and future state of science

including present concerns of “a theory of everything”

From the reading. . .

“Today, the whole of nature is laid open before us as a system of in-

terconnections and processes which have been, at least in their main

features, explained and comprehended.”

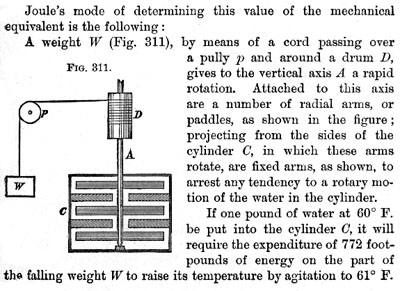

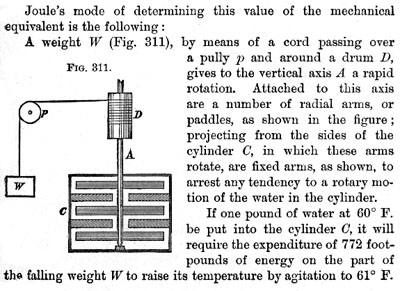

Mechanical Equivalent of Heat, from Denison Olmsted, An Introduction

to Natural Philosophy, 1844, 341.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

319

Chapter 27. “Science of Natural Processes” by Frederick Engels

Søren Kierkegaard, Journals, 1850

“It is clear enough that ‘this generation’ tends to put natural science in

the place of religion.”

Topics Worth Investigating

1. What are some of the advantages of a philosophy of mechanistic ma-

terialism?4 What are some disadvantages?

2. What are the implications of the unification of the sciences for the

possibility of a theory of ethics? Is political science reducible to

psychology, psychology reducible to biology, biology reducible to

biochemistry, and chemistry reducible to physics? Are all human

achievements, then, ultimately just patterns of matter and motion?

3. Has life been chemically created from “non-living” molecules in the

laboratory? How precise can the distinction between living things and

non-living things be made? How is it made by contemporary science?

4. If science were to develop “a theory of everything,” would religion

still be an essential part of the human experience? First explain and

then justify your position.

4.

The term “dialectical materialism” was not originally used by either Marx or

Engels. “Historical materialism” is essentially an economic thesis. Ed.

320

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 27. “Science of Natural Processes” by Frederick Engels

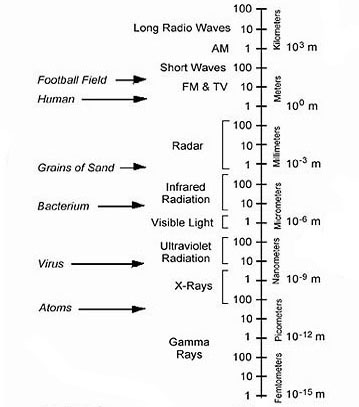

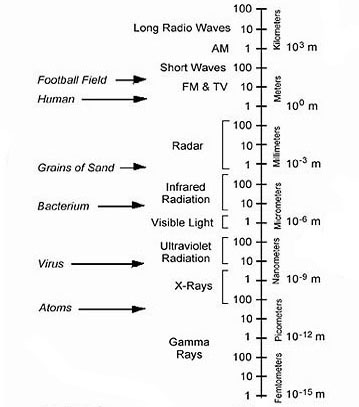

Electromagnetic Spectrum, NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

321

Chapter 28

“A Science of Human

Nature” by John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill, Thoemmes

About the author. . .

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was entirely home-schooled by his father

and was subjected to a remarkable education. His autobiography is rec-

ommended reading in large part because it shows the dangers of an in-

tensely intellectual education which neglects the emotional aspects of life.

His father secured for him a position in the East India Company which

provided him the opportunity for continuing the utilitarian tradition be-

gun by Jeremy Bentham. He spent his life advancing a logical and sci-

entific approach to social and political problems. His Utilitarianism is

generally considered the foundational statement on the nature of happi-

322

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

ness for the individual and society. Partly as a result of reading Alexis de

Tocqueville’s Democracy in America and partly from his discussions with

Harriet Taylor, Mill feared the conformist attitude of the middle working

class threated individual freedoms and authored On Liberty which remains

a classic statement today. In his The Subjection of Women, Mill argues for

equality of freedom of the sexes in spite of the 19th century’s widespread

bias that women were of a different nature than men.

About the work. . .

In our selection from A System of Logic,1 his first significant book, Mill

argues that a science of human nature is no different from any other kind

of exact science. In astronomy, the movement of the planets can be pre-

dicted with certainty because the laws of motions and the antecedent cir-

cumstances can be, he thinks, known with certainty. The rise and fall of

the tides, on the other hand, can only be imprecisely known because local

antecedent conditions cannot be known or measured exactly. The study

of human nature is similar to tidology because of the complexity of the

factors in human action. Nevertheless, Mill argues that, in principle, both

tidology and human nature can become exact sciences.

From the reading. . .

“Any facts are fitted, in themselves, to be a subject of science, which

follow one another according to constant laws; although those laws

may not have been discovered, nor even be discoverable by our exist-

ing resources.. . . ”

1.

John Stuart Mill. A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive. New York:

Longmans, Green, and Co., 1893, Bk. VI, Ch. IV.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

323

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

Ideas of Interest from A System of Logic

1. According to Mill, what is the difference between astronomy and

tidology? Does Mill think tidology will ever be an exact science?

2. Do you think Mill believes any inexact science is only inexact because of the complexity of causes as applied in specific instances?

3. When Mill writes, “Now if these minor causes are not so constantly

accessible, or not accessible at all to accurate observation, the prin-

cipal mass of the effect may still, as before, be accounted for, and

even predicted. . . ,” is he arguing for the validity of a science based

on probability theory?

4. According to Mill, what is the ideal goal of a science ( i.e. , its perfec-

tion)?

5. Does Mill think that the study of the ideas, feelings, and acts of human

beings can, in principle, achieve the exactitude of a perfect science?

If so, would such a science preclude the possibility of the freedom of

the will?

6. If human actions cannot be accurately predicted in specific instances

because of the inexhaustible number of prior conditions, then would

deterministic conditions still obviate the possibility of free choice?

Explain your answer.

The Reading Selection from A System of

Logic

[Human Nature as a Subject of Science]

It is a common notion, or at least it is implied in many common modes of

speech, that the thoughts, feelings, and actions of sentient beings are not

a subject of science, in the same strict sense in which this is true of the

objects of outward nature. This notion seems to involve some confusion

of ideas, which it is necessary to begin by clearing up.

324

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

Any facts are fitted, in themselves, to be a subject of science, which follow

one another according to constant laws; although those laws may not have

been discovered, nor even be discoverable by our existing resources.. . .

It may happen that the greater causes, those on which the principal part of

the phenomena depends, are within the reach of observation and measure-

ment; so that if no other causes intervened, a complete explanation could

be given not only of the phenomenon in general, but of all the variations

and modifications which it admits of. But inasmuch as other, perhaps many

other causes, separately insignificant in their effects, co-operate or conflict

in many or in all cases with those greater causes, the effect, accordingly,

presents more or less of aberration from what would be produced by the

greater causes alone. Now if these minor causes are not so constantly ac-

cessible, or not accessible at all to accurate observation, the principal mass

of the effect may still, as before, be accounted for, and even predicted; but

there will be variations and modifications which we shall not be competent

to explain thoroughly, and our predictions will not be fulfilled accurately,

but only approximately.

[The Theory of the Tides]

It is thus with the theory of the tides.. . .

[The] circumstances of a local or causal nature, such as the configuration

of the bottom of the ocean, the degree of confinement from shores, the

direction of the wind, &c., influence in many or in all places the height

and time of the tide; and a portion of these circumstances being either not

accurately knowable, not precisely measurable, or not capable of being

certainly foreseen, the tide in known places commonly varies from the

calculated result of general principles by some difference that we cannot

explain, and in unknown ones may vary from it by a difference that we are

not able to foresee or conjecture.. . .

Astronomy was once a science, without being an exact science. It could

not become exact until not only the general course of the planetary mo-

tions, but the perturbations also, were accounted for, and referred to their

causes. It has become an exact science, because its phenomena have been

brought under laws comprehending the whole of the causes by which the

phenomena are influenced. . .

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

325

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

The Asteroid Ida, NASA

Tidology, therefore, is not yet an exact science; not from any inherent in-

capacity of being so, but from the difficulty of ascertaining with complete

precision the real derivative uniformities.. . .

[Aspects of a Science of Human Nature]

The science of human nature is of this description. It falls far short of the

standard of exactness now realized in Astronomy; but there is no reason

that it should not be as much a science of Tidology is, or as Astronomy

was when its calculations had only mastered the main phenomena, but not

the perturbations.

The phenomena with which this science is conversant being the thoughts,

feelings, and actions of human beings, it would have attained the ideal

perfection of a science if it enabled us to foretell how an individual would

think, feel, or act through life, with the same certainty with which astron-

omy enables us to predict the places and the occultations of the heavenly

bodies. It needs scarcely be stated that nothing approaching to this can

be done. The actions of individuals could not be predicted with scientific

accuracy, were it only because we cannot foresee the whole of the circum-

326

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

stances in which those individuals will be placed. But further, even in any

given combination of (preset) circumstances, no assertion, which is both

precise and universally true, can be made respecting the manner in which

human beings will think, feel, or act. This is not, however, because every

person’s modes of thinking, feeling, and acting do not depend on causes;

nor can we doubt that if, in the case of any individual, our data could

be complete, we even now know enough of the ultimate laws by which

mental phenomena are determined to enable us in many cases to predict,

with tolerable certainty, what, in the greater number of supposable com-

binations of circumstances his conduct or sentiments would be. But the

impressions and actions of human beings are not solely the result of their

present circumstances, but the joint result of those circumstances and of

the characters of the individuals; and the agencies which determine human

character are so numerous and diversified, (nothing which has happened

to the person throughout life being without its portion of influence,) that in

the aggregate they are never in any two cases exactly similar. Hence, even

if our science of human nature were theoretically perfect, that is if we

could calculate any character as we can calculate the orbit of any planet,

from given data; still, as the data are never all given, nor ever precisely

alike in different cases, we could neither make positive predictions, nor

lay down universal propositions.

From the reading. . .

“. . . we even now know enough of the ultimate laws by which mental

phenomena are determined to enable us in many cases to predict, with

tolerable certainty. . . ”

Inasmuch, however, as many of those effects which it is of most impor-

tance to render amenable to human foresight and control are determined

like the tides, in an incomparably greater degree by general causes. . . it

is evidently possible, with regard to all such effects, to make predictions

which will almost always be verified, and general proposition which are

almost always true. And whenever it is sufficient to know how the great

majority of the human race, or of some nation or class of persons, will

think, act, feel, and act, these propositions are equivalent to universal ones.

For the purposes of political and social science this is sufficient. [A]n ap-

proximate generalisation is, in social inquiries, for most practical purposes

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

327

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

equivalent to an exact one; that which is only probable when asserted of

individual human beings indiscriminately selected, being certain when af-

firmed of the character and collective conduct of masses. . . .

[The Science of Human Nature]

The science of Human Nature may be said to exist in proportion as the

approximate truths which compose a practical knowledge of mankind can

be exhibited as corollaries from the universal laws of human nature on

which they rest, whereby the proper limits of those approximate truths

would be shown, and we should be enabled to deduce others for any new

state of circumstances, in anticipation of specific experience.

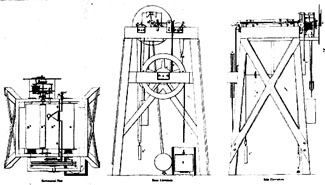

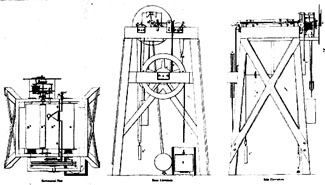

Saxon Self-Registering Tide Gauge (horizontal, rear, and side elevation

views), NOAA, Historic C&GS Collection

Related Ideas

John Stuart Mill Links (http://www.jsmill.com/). J. S. Mill. Extensive links to online versions of Mill’s writings, articles, and letters.

328

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

Chapter 28. “A Science of Human Nature” by John Stuart Mill

Mill, John Stuart (http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/M/MI/MILL_JOHN_\

STUART.htm). The 1911 Edition Encyclopædia. The “John Stuart Mill”

entry in the classic 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

John Stuart Mill (http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/mill/). Stanford Ency-

clopedia of Philosophy. A thoroughly reliable guide to Mill’s works by

Fred Wilson.

From the reading. . .

“Even if our science of human nature were theoretically perfect, . . . we

could neither make positive predictions, nor lay down universal propo-

sitions.”

Topics Worth Investigating

1. If psychology were to be an exact, or to use Mill’s phrase, “ a per-

fect” science, then specific human acts could be accurately predicted.

Would a prediction be accurate if the person about to act becomes

aware of the prediction prior to the act itself? Does the fact that a

prediction can be known in advance disprove the possibility of pre-

dicting accurately or is that fact just one more antecedent condition?

Thoroughly explain your view.

2. Is it merely a coincidence that Mill’s phrase, repeated several times in

this chapter, concerning the aspects of the science of human nature as

applying to “the thoughts, feelings, and actions” correspond to three

of the four psychological types analyzed by C. G. Jung: the thinking,

feeling, and sensation types (the fourth, the intuitive type, is omitted)?

3. Do you think that a probabilistic science such as meteorology would

qualify on Mill’s outlook as an exact science? See his thoughts on this

question in his A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive, Book.

VI, Chapter IV.

Reading For Philosophical Inquiry: A Brief Introduction

329

Chapter 29

“Coherence Theory of

Truth” by Harold H.

Joachim

Merton College, Oxford, Library of Congress

About the author. . .

The Idealist Harold H. Joachim (1868-1938), a professor of logic at Mer-

ton College, Oxford, is one of several philosophers who formulated an

idealist conception of truth. His theory articulated the concept of “truth-

or-knowledge.” Joachim’s teaching influence helped maintain British Ide-

alism as a viable philosophy until the outbreak of World War II. His notion

of truth as a “living and moving whole” as stated below in our reading se-

330

Chapter 29. “Coherence Theory of Truth” by Harold H. Joachim

lection from “The Coherence-Notion of Truth” in The Nature of Truth; An

Essay resembles the dialectic in Hegelian idealism.

About the work. . .

In his The Nature of Truth; An Essay,1 Harold H. Joachim gives one of the

classic statements of the coherence theory of truth. On his view, human

truth is incomplete, for there can be no absolute truth unless the whole

system of knowledge could be completed. Whatever is true not only is

consistent with a system of other propositions but also is true to the extent

that it is a necessary constituent of a systematic whole. Joachim empha-

sizes that since the truth is a property of the whole, individual propositions

are only true in a derivative sense—literally they are partly true and partly

false. Only the system of an extensive body of propositions as a whole can

be rightly said to be true.

From the reading. . .

“Truth, we have said, is in its essence conceivability or systematic co-

herence. . . ”

Ideas of Interest from The Nature of Truth

1. Explain Joachim’s characterization of what is conceivable. How does

his use of the term differ from a good lexical definition of “conceiv-

able”?

2. Summarize Descartes’ the