CHAPTER VI

SUCCESSFUL MONOPLANES

WHILE the biplane borrows the general principles of flight from the birds, the monoplane carries us a step further and almost exactly reproduces their form and movement. Seen high aloft, with wings outspread, the monoplanes look like great eagles as, gracefully, but very noisily, they rise and fall in long, sweeping curves. The monoplane being a much lighter machine and less complicated is therefore cheaper to build than any multiplane model. Several of the successful models ride the air very steadily and have proven themselves capable of making long and difficult air journeys.

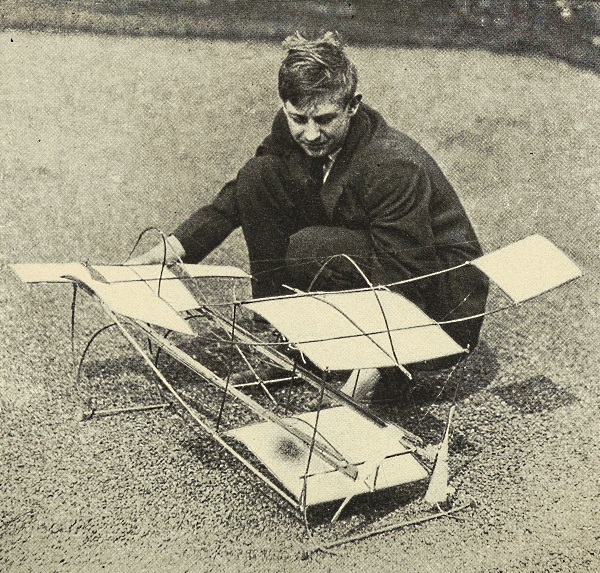

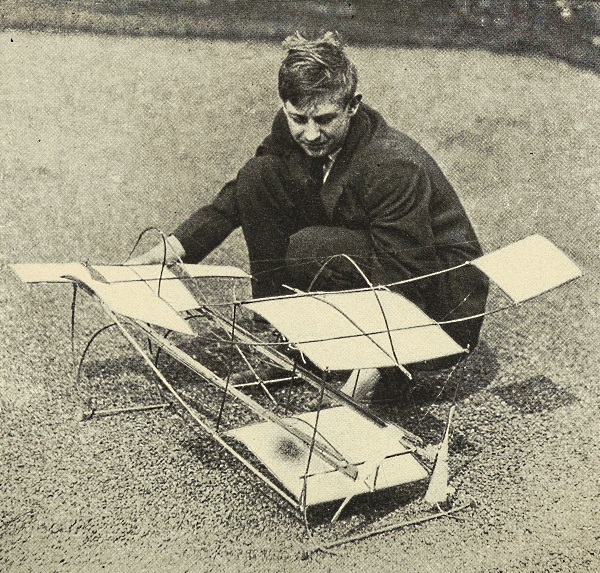

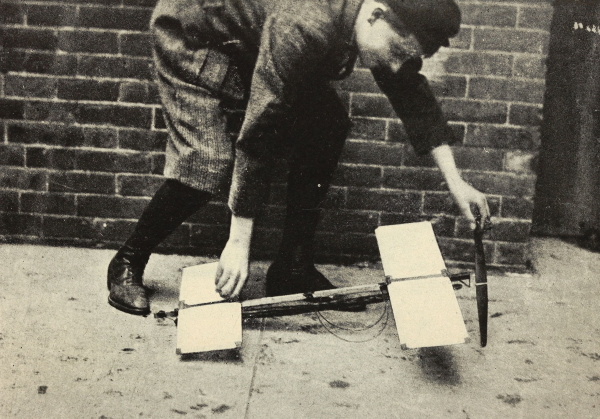

PLATE XXVII.

An Aëroplane with Paper Wings.

Some aviators believe that the monoplane type, highly developed, to be sure, will some day be adopted for great commercial airships. Even in its present form, these mechanical birds look very shipshape. The pilot can find a more comfortable seat among these wings than in the biplane forms, and it takes little imagination to picture these airships, greatly enlarged, carrying comfortable cabins filled with air voyagers. The most successful model aëroplanes, by the way, are of the monoplane form.

The first monoplane to make an extended flight was the Bleriot. Its inventor had worked with Voisin in the experiments above the River Seine at Paris in 1906, and beginning with short flights of only a few yards worked his way step by step. The machine in which he crossed the English Channel in 1909, and made several remarkable cross country flights, was his eleventh model.

Bleriot’s most successful model consists of only two wings curved upward, mounted on a long motor base which measures twenty-six and one half feet in length. The body of the monoplane, which is made of ash and poplar, tapers to a point in the rear and is partially covered with “Continental fabric,” similar to balloons. The front or main wing is twenty-five and a half feet in width with a surface of 159 square feet. The rear plane measures only six feet in width, and three feet in depth and is equipped with moveable tips or horizontal rudders two feet square at either side. The vertical rudder for steering to right or left, is carried behind the frame. The planes are braced by a series of stay wires running in all directions.

Unlike the biplane, the motor of the monoplane is placed in front of the wings. The blades of the propeller, which are unusually broad, measure less than seven feet from tip to tip. The pilot’s seat is inside the motor frame near the rear edge of the main wing, and with its high back and sides appears to be a comfortable place to sit. It has the disadvantage, however, of being directly behind the motor, so that a draft of air strikes the driver in the face.

The pilot keeps his machine on an even keel by flexing the tips of the planes, much the same as in the Wright model. The tips of the main plane and of the two horizontal rudders are connected with a single lever, which gives the pilot perfect control of them. The horizontal rudders may be turned to steer the aëroplane up or down in the same way. The vertical rudder for turning the aëroplane from right to left, is operated by a foot lever.

The Bleriot monoplane weighs about 500 pounds, so that it carries about four pounds for every square foot of wing surface, or thirteen pounds per square foot, which is from two to four times greater than is the case of any biplane. The machine is mounted on three wheels, two at the front and one near the rear, just forward of the rudders. It has a speed of nearly forty miles an hour.

All the present monoplane models follow the same general plan of placing their propellers and larger planes in front and their horizontal rudder for vertical steering in the rear. The idea is gaining ground, however, that it would be better if this arrangement was reversed, and they flew with what is now the tail in front. The theory of this arrangement is that if the edge of the lifting planes is presented to the air, they would answer the helm much better, as has been proven in the biplane forms. The experiment of reversing the monoplane forms has been tried in model aëroplanes with great success.

The heaviest and largest of the monoplanes at present is the Antoinette model, which is the invention of M. Levasseur. It looks like a great dragon fly, and has proven itself very steady in flight. The main wings, measuring forty-two feet in width seem to be arched unusually high from front to rear, and taper rather sharply at the ends. Their total lifting surface is a trifle over 300 feet. In some of the Antoinette models the wings are set in the form of a broad, dihedral angle. The monoplane is driven from a seat in the body of the frame as the Bleriot model, but moved slightly farther back. The rear horizontal rudder is controlled by a large wheel at the left of the pilot’s seat, while a corresponding wheel on the right controls the small hinged wings at the outer edge of the main plane. The pilot turns his airship from right to left by merely pressing two foot pedals connected with the vertical rudder in the rear. In the later models, the dihedral angle has been abandoned and the front planes set horizontally.

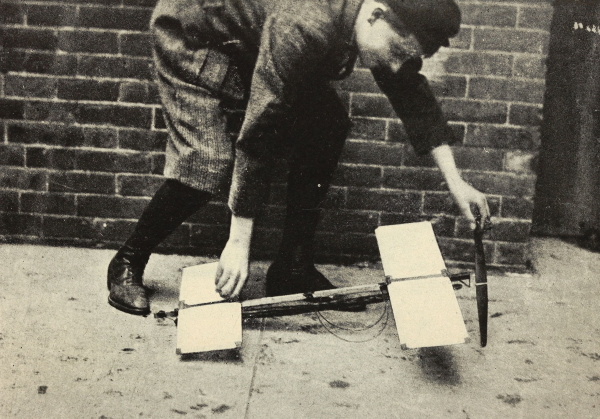

A Very Simple Monoplane for Beginners.

The most novel feature of the Antoinette model is the form and control of the rear rudders and stability planes. The model carries two vertical rudders for turning the craft to the right or left, and a large horizontal rudder for vertical steering, extending far out behind at the end of the main body. All of these rudders are triangular in shape, tapering to a point in the rear. The Antoinette has proved, it is believed, that the corners of square rudders may be removed, without affecting their guiding qualities, thus saving considerable surface and weight. It would seem, on general principles, that just the reverse would be the case. The builder of model aëroplanes may take a leaf from the log of this airship.

The Antoinette stability planes are placed just forward of the rudders, and are triangular in shape, but with somewhat narrow ends pointing toward the front. Two of these planes are carried horizontally and one vertically, the vertical planes being above the horizontals. The chief fault of this model is that the rear horizontal stability plane, being perfectly flat, exerts little lifting power. The method of warping the tips of the planes, the same as in the Wright aëroplane, works well with this model, and the flights, are as a rule, remarkable steady. The machine lands on wooden skids, carried well forward, connected with the frame by flexible joints. It is supported in the rear by two wheels under the center of the planes.

The Santos Dumont monoplane is, so far, the smallest and lightest monoplane to make a successful flight. It is the aëronautical runabout, and, although it has made no very extended air journeys, it has introduced several interesting features. Its owner has flown several miles across country in his little craft, housed it in an ordinary stable while making a call, and then, starting from the front lawn, flown home again without assistance of any kind. His machine may be counted upon to fly at the rate of about thirty-seven miles an hour. It weighs only 245 pounds without the pilot.

The main plane is set at an angle so that, seen from the front, the wings rise from the center, but later bend down toward the tips. The front or entering edge is also elevated to an unusually high degree, giving it the appearance of a rather flat umbrella. The pilot sits underneath this front plane just below the center. The stability of this plane is maintained by fixing the ends in the usual manner. The wires connecting with the ends of the planes, are carried to a lever which is attached to the pilot’s back. The pilot, therefore, without using his hands, but merely by swaying his body from side to side, can warp the planes and bring his craft to an even keel.

The Santos Dumont monoplane carries no regular stability plane at the rear, but depends for its support and guidance upon a small vertical and horizontal rudder at the end of its very short frame. These two rudders bisect one another, or in other words, half of the vertical rudder is above and half below the horizontal rudder, while half of the horizontal rudder is on one side and half on the other of the vertical rudder. They are attached to a single rigid framework, so that both move as a whole by means of a universal joint. The rudders, used for ascending and descending, are operated by a lever, while the rudders used for horizontal steering are controlled by a wheel.

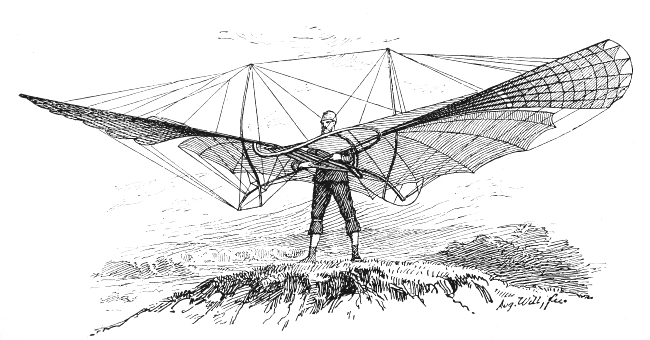

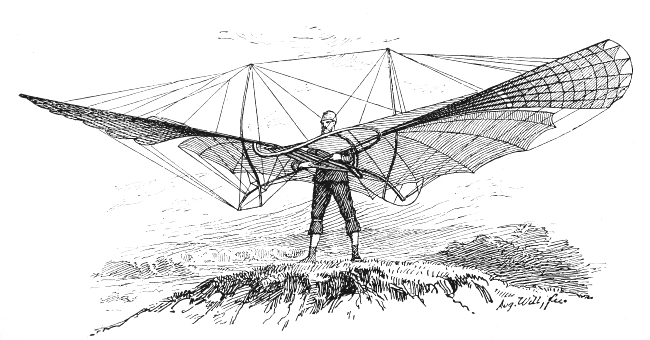

Otto Lilienthal about to Take Flight.

The aëroplane is mounted on two wheels, placed at the front of the frame and a vertical strut at the rear, thus reversing the arrangement of the Antoinette. This adjustment works well in practice, and the Santos Dumont holds the record for rising from the ground in the shortest distance. It has risen in six and a quarter seconds after traveling only 230 feet. The area of its wings is only 110 square feet and its propeller consisting of double wooden blades measures only six feet three inches in diameter. It carries a 30 H. P. motor.

The R. E. P. monoplane, the name being formed by the initials of its inventor, Robert Esnault-Pelterie, is an experiment along new lines. Its inventor believes that the wires and struts of the monoplane in vibrating, offer considerable resistance to the air and seriously retard its forward movement. His monoplane has, therefore, been constructed practically without stays, wires, or rods. The monoplane is graceful in form, light and compact, although somewhat expensive to build.

The main frame of the airship is made of steel girders with a broad surface and tapering to a sharp edge at the bottom. It is covered completely with cloth, thus forming a vertical stability plane of considerable area. The motor and propeller are carried at the front of the frame, while the pilot’s seat is fixed inside the frame, just back of the machinery.

The main planes have a span of thirty-five feet six inches. They extend from either side of the frame, and taper slightly toward their outer edges. Two large rudders are carried at the rear of the frame. The vertical rudder for horizontal steering is attached to an extension of the main frame and the horizontal rudder projects from the end at a higher level. A fixed vertical stability plane or fin extends along the main frame back of the pilot’s seat. The warping of the plane and the control of both rudders is accomplished by levers placed convenient to the pilot’s hand.

The R. E. P. model, alone among the aëroplanes, is equipped with a four blade propeller. It measures six feet six inches in diameter, and is driven at the speed of 1400 revolutions per minute. The speed of the craft is remarkable since it has flown for short distances at the rate of forty-seven miles an hour. Its weight, 780 pounds, is not unusual.

An entirely new idea has been introduced in mounting this model. It rests upon only two wheels, one at the front, the other at the end of the central frame. Wheels are also attached to the outer edges of the main plane. When at rest, the model tilts over to one side or the other and rests on one of these wheels. Once the motor has been started, the machine quickly rights itself, as the speed increases, and runs along on two wheels.