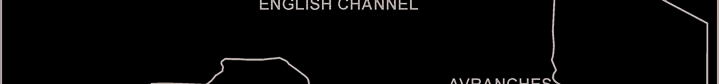

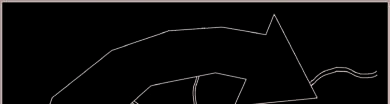

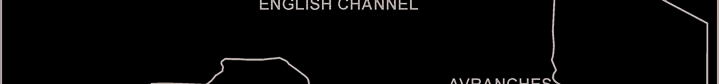

Ultimately they reached a compromise. General Middleton’s VIII Corps was tasked to

secure the peninsula, and the bulk of Patton’s Army, three Army corps, was turned

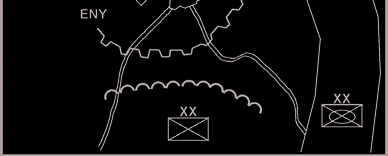

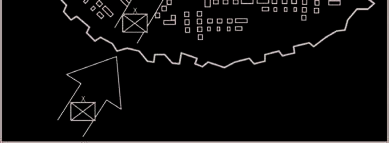

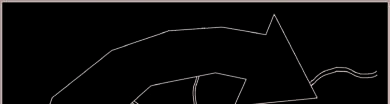

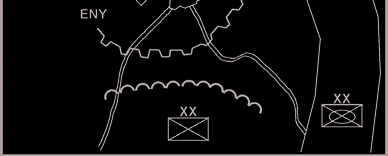

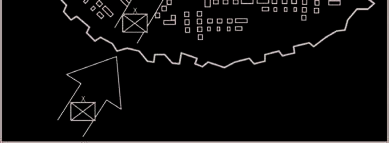

northeast to exploit the operational collapse of the main German defenses. (See

figure 7-1.)

Figure 7-1. Initial attack in Brittany

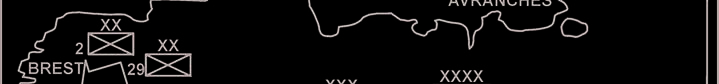

Middleton’s corps sprinted into the peninsula with the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions leading the way. However, poor communications, disagreements between

commands, and contradictory orders caused the corps to hesitate before pushing the

two divisions to continue to exploit toward the ports. The result: the 6th Armored

Division missed an opportunity to seize Brest against light resistance by one day.

The 4th Armored Division, after capturing the smaller port of Vannes, was also

frustrated on the approaches to Lorient. The American reaction to the inability to

rapidly seize the ports demonstrated an understanding of changing circumstances.

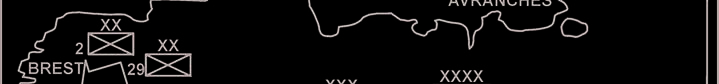

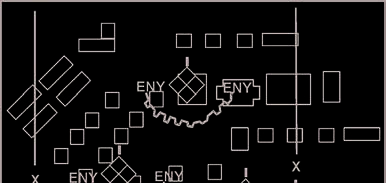

The 6th Armored Division turned the attack at Brest to the 8th Infantry Division and then relieved the 4th Armored Division at Lorient. The 4th Armored was moved to

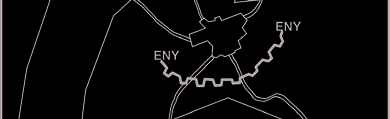

rejoin the rest of Third Army exploiting to the east and north. Ultimately Brest fell to VIII Corps on 19 September after a 43-day siege by three infantry divisions. The

victory yielded 36,000 German prisoners of war (POWs). However, the German

defense and demolitions of the port left the port without an impact on the logistic

situation of the allies. Brest cost the U.S. Army almost 10,000 casualties and the

commitment of significant supplies. The experience convinced commanders to

surround and bypass the other major Brittany ports. Lorient and Saint Nazaire

remained under German control, deep in allied territory, until the war ended ten

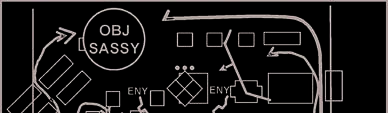

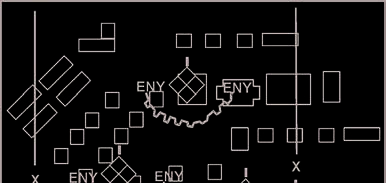

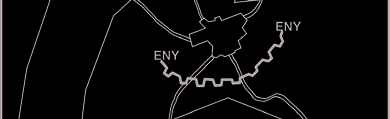

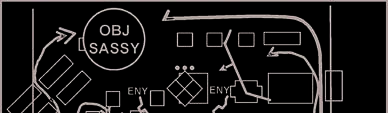

months later (see figure 7-2).

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-3

Chapter 7

Figure 7-2. Subsequent disposition of forces in Brittany

The operational lessons of the Brittany campaign are numerous. First, commanders

are responsible to continually assess assumptions and decisions made during

planning based on the changing circumstances of the battlefield. This includes the

planning decision to conduct urban offensive operations. When the allies arrived at

the Brittany Peninsula, the focus of the operational maneuver was no longer securing logistics facilities but exploiting the breakthrough at Saint Lo and the disintegrating the German defense. The bulk of Third Army then was turned to the north and east

rather than west into the peninsula.

The Brest experience also demonstrates that the costs of urban offensive operations

are continually assessed against the operational value of the objective. This lesson was applied to the cities of Lorient and Saint Nazaire. The cities were never seized from the Germans because their logistic value failed to warrant the required

resources to take them. German retention of the ports had no major adverse effect

on the overall campaign.

Another lesson is that commanders cannot allow urban operations to disrupt the

tempo of other offensive operations. One German goal of defending the ports was to

disrupt the rapid tempo of the U.S. exploitation. They failed to achieve this goal

because General Bradley continued the exploitation with the bulk of Third Army and

executed the original plan with only a single corps.

Finally, commanders cannot allow emotion to color their decision to conduct or

continue UO. The failure of 6th Armored Division to seize Brest rapidly caused some

commanders to believe that Brest had to be captured because the prestige of the

Army was committed to the battle. Costs of the continuing combat operations to seize Brest were significant. These resources might have been better committed

elsewhere in the theater.

7-7. Tactical tempo is also important in urban combat. Because of the complex terrain, defending forces can rapidly occupy and defend from a position of strength. Once Army forces initiate tactical offensive 7-4

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Offensive Operations

operations, they cannot allow the threat to set the tempo of the operation. Instead, attacking forces seek to maintain a high tempo of operations. However, the tactical tempo of urban operations differs from operations in other terrain. Not necessarily slow, it requires a careful balance of preparation, speed, and security. In terms of unit fatigue, resource consumption, and contact with the threat, the tempo of most urban offensive operations may be rated as very high. On the other hand, in distances traveled and time consumed to achieve objectives, the tempo of many urban offensive operations might be rated as slow. The urban battlefield’s density concentrates activity and consumes resources in a relatively small area. The lack of terrain seized or secured is not to be construed to mean a low tempo in the battle. Although the tempo may seem excruciatingly slow at higher levels of command and exceeding fast at lower, tactical levels, in reality, the natural tempo of urban operations is not faster or slower than other types of operations, merely different. Creating and operating at a tempo faster than an opponent can maintain, however, can favor forces which are better led, trained, prepared, and resourced.

7-8. A high tactical tempo in urban offensive operations challenges logisticians to provide for the increased consumption of munitions and degrades soldiers’ physical capabilities. Commanders must anticipate these challenges and develop the means and abilities to overcome them. In the past, these challenges forced commanders to conduct urban offensives cyclically. They used night and other periods of limited visibility to resupply, rest, and refit forces. The environment influenced the tempo of their operations. This type of “battle rhythm” resulted in the forces spending each new day attacking a rested threat that was in a well-prepared position.

7-9. Army forces must maintain the tempo. Offensive operations continue even during darkness.

Moreover, Army forces increase the tempo of operations at night to leverage the limited visibility capabilities, increased situational understanding, training, and INFOSYS that give an advantage to Army forces in all environments. To overcome the physical impact of the environment on soldiers, commanders can retain a large reserve to rotate, continuing offensive operations at night. The force that fights in daylight becomes the reserve, rests, and conducts sustaining operations while another force fights at night.

Army forces can then maintain the tempo of operations and leverage technological advantages in urban offensive combat.

7-10. Tempo in UO does not necessarily mean speed. Offensive operations balance speed, security, and adequate firepower. Commanders must plan for the complex tactical environment and the requirements to secure flanks and airspace as the operation progresses. Mission orders allow subordinate units to make the most of tactical advantages and fleeting opportunities.

AUDACITY

7-11. Audacity is a simple plan of action, boldly executed. Superb execution and calculated risk exemplify it. In an urban attack, a thorough understanding of the physical terrain can mitigate risk. The terrain’s complexity can be studied to reveal advantages to the attacker. Audacity can also be embodied in an operation by inventively integrating and coordinating the direct action tasks of SOF throughout the operation. Combining SOF actions with conventional attacks can asymmetrically unhinge a threat’s defensive plan. Well trained Soldiers confident in their ability to execute urban offensive operations foster audacity.

URBAN OFFENSIVE OPERATIONS AND BATTLEFIELD

ORGANIZATION

7-12. Urban offensive operations, like all operations, are arranged using the overall battlefield organization of decisive, shaping, and sustaining operations. Each operation is essential to the success of an urban offensive, and usually two or more of these operations occur simultaneously. Decisive operations are attacks that conclusively determine the outcome of UO. These attacks strike at a series of decisive points and directly lead to neutralizing the threat’s center of gravity. Shaping operations in urban offensive operations create the conditions for decisive operations. In UO, much of the shaping effort focuses on isolation, which is critical in both major operations and tactical battles and engagements. Sustaining 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-5

Chapter 7

operations in urban offensive operations ensure freedom of action. They occur throughout the area of operations (AO) and for the duration of the operation.

DECISIVE OPERATIONS

7-13. A tactical commander fights decisive urban combat, whereas commanders conducting a larger major operation influence urban combat by setting the conditions for tactical success. Higher commanders may directly influence urban offensive operations by operational maneuver, by coordinating joint fires, by closely coordinating conventional forces, or with SOF.

7-14. Tactical urban offensive operations quickly devolve into small-unit tactics of squads, platoons, and companies seizing their objectives. The compartmented effect of the terrain and the obstacles to command and control of small units, especially once they enter close combat inside buildings or underground, often restricts the higher commander’s ability to influence operations. Commanders can influence the actions of subordinates by clearly identifying the decisive points leading to the center of gravity; using mission orders (as discussed in Chapter 5); developing effective task organizations; synchronizing their decisive, shaping, and sustaining operations; and managing transitions.

7-15. Like all operations, successful decisive operations in UO depend on identifying the decisive points so the forces can destroy or neutralize the threat’s center of gravity. Seizing a key structure or system that makes the threat’s defense untenable; interdicting a key resupply route that effectively isolates the threat force from his primary source of support; or isolating the threat so that his force can no longer influence friendly activity may be more effective than his outright destruction.

7-16. Commanders must select the right subordinate force for the mission and balance it with appropriate attachments. Higher commanders do not direct how to organize the small tactical combined arms teams, but they must ensure that subordinates have the proper balance of forces from which to form these teams.

Successful urban offensive operations require small tactical combined arms teams. Urban offensive operations require abundant infantry as the base of this force. However, successful urban combat requires a combined arms approach adjusted for the conditions of the environment. In urban offensive operations, it will normally not be a question of whether include armor and mechanized elements but, rather, how best to accomplish this task organization. Precision-capable artillery systems generally support urban operations better than unguided rocket artillery.

7-17. Divisions entering urban combat may require additional resources. These resources include military intelligence support in the form of linguists, human intelligence (HUMINT) specialists, and unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). Engineering assets will be at a premium; the task organization of a task force executing the decisive operation may require a one-to-one ratio of engineer units to combat units. Corps and higher engineering support may be necessary to meet these requirements and to repair vital and specialized infrastructure. A tailored and dedicated support battalion or group may need to assist in providing anticipated support to a displaced and stressed civil population. Finally, divisional CA units may require augmentation to deal with NGOs and civilian government issues.

7-18. Successfully conducting decisive operations in the urban environment requires properly synchronizing the application of all available combat power. Army forces have a major advantage in the command and control of operations. Commanders can use this advantage to attack numerous decisive points simultaneously or in rapid succession. They also use it to attack each individual decisive point from as many directions and with as many different complementary capabilities as possible. Commanders must completely understand urban environmental effects on warfighting functions to envision and execute the bold and imaginative operations required. Significantly, these operations require that C2 systems account for the mitigating effects of the environment as execution occurs.

7-19. Properly synchronized actions considerably enhance the relative value of the combat power applied at the decisive points. They present to the threat more requirements than he has resources with which to respond. Synchronized IO and multiple maneuver actions paralyze the threat’s decision-making capacity with information overload combined with attacks on his C2 systems. Additionally, well-synchronized actions limit the time the threat has to make decisions and forces him into bad decisions. In the urban 7-6

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Offensive Operations

environment, these effects are enhanced because C2 systems are already strained, poor decisions are harder to retrieve, and units that do not react effectively are more easily isolated and destroyed.

SHAPING OPERATIONS

7-20. Shaping operations that support the urban attack separate into those focused on isolating the threat and all others. Army forces isolate the threat to ensure successful urban offensive operations. Depending on the threat reaction to isolation efforts and the nature of the threat center of gravity, this task may become decisive. Other shaping operations include those common to all offensive operations and others unique to urban operations. Unique urban shaping operations may include securing a foothold in a well-fortified defensive sector, securing key infrastructure, or protecting noncombatants. Because of the nature of UO, shaping operations may consume a much larger proportion of the force than during other operations and may take place both inside and outside the urban area (see Applying the Urban Operational Framework: Panama in Chapter 5). By successfully isolating a threat force, the force needed to conduct the decisive operation may be relatively small.

SUSTAINING OPERATIONS

7-21. Commanders conducting urban offensive operations must ensure security of the sustaining operation and bases; in many situations, protecting lines of communications (LOCs) and sustaining operations may be the greatest vulnerability of the attacking force. Those supporting an urban offensive are tailored to the urban environment and are well forward. Ideally, the supporting forces closely follow the combat forces and move within or just outside the urban area as soon as they secure an area. Operating in the urban area during offensive operations allows the sustaining operation to take advantage of the defensive attributes of the environment for security purposes.

7-22. Counterattacks against sustaining operations may take the form of special operations activities aimed at LOCs leading to or within the urban area. Choke points—such as bridges, tunnels, and mountain passes—are vulnerable to these attacks and may require combat forces to protect them. Threat forces attack the LOC to blunt the Army’s combat power advantage in the urban area.

7-23. Attacks against the LOC into the urban area may also attempt to isolate the attacking Army forces from its sustainment base. Isolated forces in an urban area are greatly disadvantaged. Commanders must plan and aggressively execute strong measures to protect their LOC, even if it requires reduced combat power to execute their offensive operation.

7-24. Sustaining operations anticipate the volume and unique logistics requirements of urban operations.

Specialized individual equipment—such as grappling hooks, ladders, and pads—is identified and provided to troops in quantity before they are needed. Forces stockpile and distribute their attacking units’ special munitions requirements including small arms, explosives, and grenades of all types, precision artillery munitions, and mortar ammunition. Forces also supply transport to move the resources rapidly forward, both to and through the urban environment. Sustaining operations cannot rely on “operational pauses” to execute their tasks. Commanders must plan to continuously supply resources and capabilities to the most forward combatants as offensive operations advance.

7-25. Sustaining operations also anticipate the growth of sustainment requirements as Army forces secure and take responsibility for large portions of the urban area. The success of Army urban offensive operations will often uncover the civil population in former threat occupied areas. It may attract the civil population from sections of the urban area where the Army is not operating to areas occupied by Army forces. Rural populations may migrate to the urban area as the result of successful Army offensive operations.

7-26. Army forces may be required to take initial responsibility to provide for the urban population. This consideration is integrated into logistics planning and organization from the start of the planning process.

To be successful and efficient in such a situation, sustainment planning includes Army civil affairs (CA) specialists and local government representatives. It also integrates and consults with the international community and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that might augment or supplement Army sustainment capabilities.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-7

Chapter 7

FORMS AND TYPES OF URBAN

OFFENSE

7-27. Traditional forms of offensive maneuver include

envelopment, turning movement, infiltration, penetration,

and frontal attack. Traditional types of offensive

operations are movement to contact, attack, exploitation,

and pursuit. These traditional forms and types listed

apply to urban combat. Some have greater application to

an urban environment than others do. Moreover, success

will belong to commanders who imaginatively combine

and sequence these forms and types throughout the

depth, breadth, and height of the urban battlefield. This is

true at the lowest tactical level and in major operations.

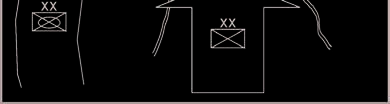

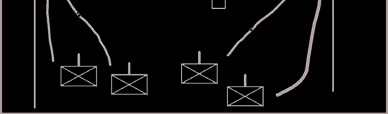

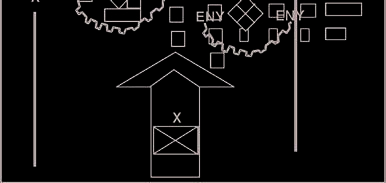

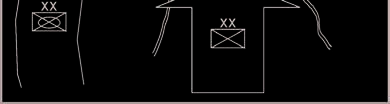

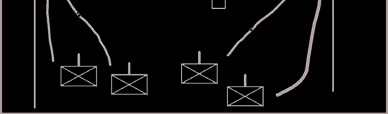

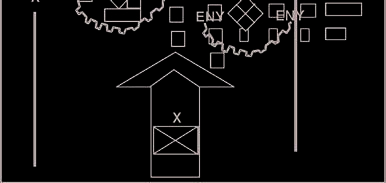

Figure 7-3. Envelopment isolates an

urban area

FORMS OF OFFENSIVE MANEUVER

Envelopment

7-28. The envelopment is the ideal maneuver for

isolating threat elements in the urban area or isolating the

area itself. A deep envelopment effectively isolates the

defending forces and sets the conditions for attacking the

urban area from the flank or rear. Yet, enveloping an

objective or threat force in the urban area is often harder

since achieving speed of maneuver in the environment is

so difficult (see figure 7-3). Vertical envelopment,

however, works effectively if Army fires can effectively

suppress or neutralize the threat air defense.

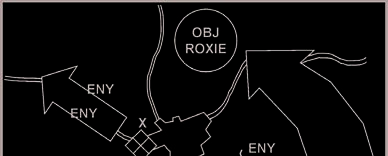

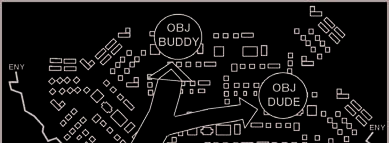

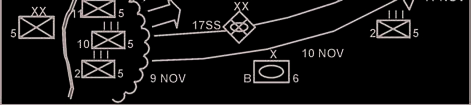

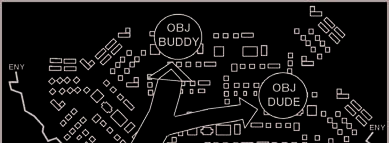

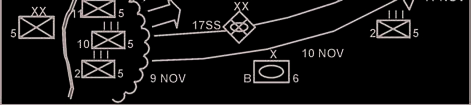

Figure 7-4. Turning movement

Turning Movement

7-29. Turning movements can also be extremely

effective in major operations (see figure 7-4). By

controlling key LOCs into the urban area, Army forces

can force the threat to abandon the urban area entirely.

These movements may also force the threat to fight in

the open to regain control of LOCs.

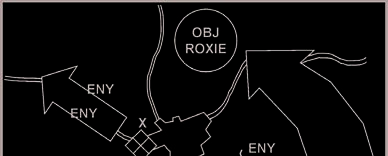

Infiltration

7-30. Infiltration secures key objectives in the urban

area while avoiding unnecessary combat with threat

defensive forces on conditions favorable to them (see

figure 7-5). This technique seeks to avoid the threat’s

defense using stealthy, clandestine movement through

all dimensions of the urban area to occupy positions of

F

igure 7-5. Infiltration

7-8

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Offensive Operations

advantage in the threat’s rear (or elsewhere).It depends on the careful selection of objectives that threaten the integrity of the threat’s defense and a superior common operational picture (COP). Well-planned and resourced deception operations may potentially play a critical role in masking the movement of infiltrating forces. The difficulty of infiltration attacks increases with the size and number of units involved. It is also more difficult when Army forces face a hostile civilian population. Under such circumstances, infiltration by conventional forces may be impossible. Armored forces are generally inappropriate for infiltration operations. However, they may infiltrate large urban areas if the threat is not established in strength and had insufficient time to prepare defenses.

Penetration

7-31. Penetration is often the most useful form of attack against a prepared and comprehensive urban defense (see figure 7-6). It focuses on successfully attacking a decisive point or on segmenting or fragmenting the defense—thereby weakening it and

allowing for piecemeal destruction. (The decisive point

may be a relatively weak or undefended area that allows

Army forces to establish a foothold for attacks on the

remainder of the urban area.) Ideally in urban combat,

multiple penetrations in all dimensions are focused at the

same decisive point or on several decisive points

simultaneously. In urban combat, the flanks of a

penetration attack are secure, and resources are

positioned to exploit the penetration once achieved.

Although always a combined arms team, rapid

penetrations are enhanced by the potential speed,

firepower, and shock action of armored and mechanized

forces.

Figure 7-6. Penetration

7-32. Importantly, commanders must consider required actions and resources that must be applied following a successful (or unsuccessful) penetration. A penetration may result in the rapid collapse and defeat of the threat defense and complete capitulation. On

the other hand, success may cause threat forces to

withdraw but leave significant stay-behind forces (or

disperse into the urban population as an insurgent-type

force) which may necessitate methodical room-to-room

clearance operations by significant dismounted forces.

Additionally, securing portions (or all) of an urban area

requires occupation by Army forces to prevent re-

infiltration of threat forces thereby further increasing

manpower requirements. Based on the factors of the

situation, commanders may conclude that over time

methodical clearance operations conducted from the

outset, while frontloading time and resource

requirements, will be less costly than a penetration

followed by systematic clearing operations.

Figure 7-7. Frontal attack

Frontal Attack

7-33. For the commander of a major operation, the frontal attack is generally the least favorable form of maneuver against an urban area unless the threat is at an obvious disadvantage in organization; numbers, training, weapons capabilities, and overall combat power (see figure 7-7). Frontal attacks require many 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-9

Chapter 7

resources to execute properly, risk dispersing combat power into nonessential portions of the area, and risk exposing more of the force than necessary to threat fires. In urban offensive combat, forces most effectively use the frontal attack at the lowest tactical level once they set conditions to ensure that they have achieved overwhelming combat power. Then the force of the frontal attack overwhelms the threat with speed and coordinated and synchronized combat power at the point of attack. The assigned frontage for units conducting an attack on an urban area depends upon the size and type of the buildings and the anticipated threat disposition. Generally, a company attacks on a one- to two-block front and a battalion on a two- to four-block front (based on city blocks averaging 175 meters in width).

Forms of Attack in the Urban Offense: Metz – 1944

In November 1944, the U.S. Third Army launched its final effort to take the French

city of Metz from the defending Germans. This was the Army’s third attempt. The first attempt had been a surprise, mounted attack. This was followed by a series of

piecemeal infantry assaults on the surrounding fortresses. Finally, a deliberate effort was made to take the city in a coordinated effort by X