5-94. Similar to PA operations, CMO are related to information operations. The nature of CMO and the need for CA personnel to develop and maintain close relationships with the urban population put CA personnel in a favorable position to collect information. CA personnel work daily with civilians, their equipment, and their records that may be prime sources of information. If used correctly, CA personnel can complement the intelligence collection process necessary to understand the dynamic societal component of the urban environment and detect significant changes. However, CA personnel are not, and cannot appear as, intelligence agents; otherwise, it will undermine their ability to interact with the civilian community.

Examples of information available to CA units include government documents, libraries, and archives; files of newspapers and periodicals; industrial and commercial records; and technical equipment, blueprints, and plans.

5-95. Overall, CA expertise is critical to a commander’s understanding of the complexities of the infrastructure and societal components of the urban area. These components (together with the terrain or physical component of the urban area) interconnect. CA forces help identify and understand the relationships and interactions between these urban components. From this understanding, commanders can anticipate how specific military actions affect the urban environment and the subsequent reactions. CA personnel help commanders predict and consider the second- and third-order effects and reactions as well as the long-term consequences. Understanding these long-term consequences helps in achieving stability and ensuring a smoother and speedier transition of the urban area back to civilian responsibility and control. Oppositely, an unconsidered short-term solution may, in the end, turn out to be the solution requiring the greatest amount of time. Poor solutions may exacerbate the situation. Others may contribute little to conflict resolution and waste precious resources (particularly time) until a more reasoned approach is formulated—one that should have been the first solution.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-23

Chapter 5

Civil-Military Reconstruction Efforts

5-96. Reconstruction efforts and activities, an integral part of CMO, should complement NGO efforts and are conducted in concert with larger urban area and nationwide projects often headed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). For example, extensive, large-scale sewer projects or major repairs to the urban area’s electrical infrastructure would be left to the USACE and USAID. When planning and conducting urban reconstruction, commanders should—

z

Keep expectations realistic. With so much to do, it is easy for Army forces to become overcommitted. Commanders must focus on the achievable, build off successes, and create constructive forward process.

z

Seek opportunities. While commanders think long-term, they should look for catalytic investment of resources. Minimal resources provided at the right time can generate significant activities resulting in increased momentum toward the desired end state.

z

Align resources with local needs. In analyzing the merit of a project, commanders must check to determine if it is supported and desired by the urban populace. Local participation in the process reinforces ownership and acceptance and eventual transition of responsibility.

z

Balance speed and quality. Commanders must balance the achievement of rapid response with quality construction and repairs.

z

Ensure efforts do not undermine locals. Army reconstruction efforts should not undermine the growth and legitimacy of local institutions and authorities.

z

Integrate in the targeting process. Commanders should routinely include approval of civil-military reconstruction products as part of the information operation’s contribution to the overall targeting process.

INTEGRATION OF CONVENTIONAL AND SPECIAL OPERATIONS

FORCES

5-97. One important Army and joint resource that commanders of a major operation can use to influence urban operations is SOF. Several types of these forces exist (including the CA forces discussed above), each with unique and complementary capabilities. They can be extremely valuable in UO for their ability to execute discrete missions with a higher degree of precision than conventional forces, to provide information, and to enhance cultural understanding. However, the challenges of using SOF include command and control; integration; coordination with conventional forces that will normally command, control, and conduct the bulk of UO tasks; and the imprudent inclination to use SOF forces for conventional purposes. The density and complexity of UO make close coordination and synchronization of conventional forces and SOF essential to mission success. The nature of the environment dictates that both forces will work in close proximity to each other; the separation in space and time between SOF and conventional forces will often be much less in urban areas than in other environments. Overall, the nature of the environment demands a synergistic combination of capabilities to achieve effects on the threat and mission success.

5-98. Successfully integrating SOF occurs with proper integration into, or coordination with, the command structure of the force conducting the UO. SOF within a theater (less CA and tactical PSYOP) ordinarily falls under joint command and control. Therefore, the commander of the major operation responsible for an urban area, if he is not a JFC, will have to coordinate through the JFC to integrate SOF capabilities into the UO. Examples of critical coordination elements include:

z

Boundaries.

z

No-fire areas. (If assigned, SOF liaison officers (LNOs) must be routinely included in targeting meetings.)

z

Coordination points.

z

The exchange of key intelligence and information.

z

Requirements to support personnel recovery contingencies.

5-24

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

Conventional and Special Forces Integration

On 20 April 2003 during OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM (OIF), an Army Special

Forces (SF) operational detachment alpha (ODA) was patrolling through villages and

secondary roads east-southeast of An Najaf. A local Iraqi approached the team and

volunteered the location of a senior Ba’ath Party official in the nearby town of

Ghamas. Unfortunately, he did not provide an exact location but rather an

approximate location and the name of the family dwelling. The ODA coordinated with

their company commander and nearby elements of the 101st Airborne Division to

conduct a raid on the residence at dawn the next day. Joint planning, preparation,

and rehearsals among the units occurred throughout the night.

At 0430, the raid convoy departed its base en route to Ghamas. The small task force

consisted of an assault team, a security team, a command and control element, and

three blocking forces composed of Soldiers from a scout platoon and antiarmor

company of the 101st. At 0515, the convoy hit the release point outside Ghamas.

The 101st vehicles moved to their blocking positions at three bridges surrounding the town. The remainder of the task force moved into the town. An interpreter quickly

found a local guide who knew where the house was located. He took the SF team to

a walled two-story dwelling with a courtyard. The security team isolated the objective and provided overwatch while the assault team forcibly seized the house and

apprehended three adult males. Among them was Abd Hamden, the target of the

raid and a senior Ba’ath Party official from Baghdad.

After a tactical interrogation, one of the men provided the location of a Fedayeen

major nearby. The SF and conventional force raided this house minutes later but only found the major’s relatives. As the Soldiers left the town with their captives, they were cheered by the locals throughout the town. Although only one small example, the

extensive coordination between SOF and conventional forces during urban

operations was a tremendous success during OIF.

SYNCHRONIZATION OF ACTIVITIES WITH OTHER AGENCIES

5-99. The population density of the urban environment, its economic and political importance, and its life-supporting infrastructure attracts many types of organizations. These organizations include—

z

Other U.S. governmental agencies.

z

International governmental organizations.

z

Allied and neutral national governments.

z

Allied and coalition forces.

z

Local governmental agencies and politicians.

z

NGOs.

5-100. Even in a major operation or campaign, many organizations operate in the area as long as possible before combat or as soon as possible after combat. Therefore, coordination with these organizations sharing the urban AO will be essential to achieve synchronization; however, effective synchronization is challenging, time consuming, and manpower intensive. The staffs of larger headquarters (divisions or higher) normally have the breadth of resources and experience to best conduct the necessary synchronization. They can effectively use or manage the organizations interested in the urban area and mitigate their potential adverse effects on UO. By taking on as much of the synchronization requirements as possible, the operational headquarters permits its tactical subordinates to remain focused on accomplishing their tactical missions. The higher headquarters should assume as much of the burden of synchronization as possible. However, the density of the urban environment will often require that smaller tactical units coordinate and synchronize their activities with other agencies and the local civilian leadership (formal and informal) simply because of their physical presence in the units’ AOs. In urban 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-25

Chapter 5

stability and civil support operations, mission accomplishment will require effective civil-military coordination and synchronization activities and measures at all levels as either a specified or implied task.

CIVIL-MILITARY OPERATIONS CENTERS

5-101. To coordinate activities among the varied agencies and organizations operating in an urban area and the local population, urban commanders can establish a CMOC. The CMOC synchronizes Army activities and resources with the efforts and resources of all others involved (see FM 41-10). This can be particularly important in stability and civil support operations where combat operations are not the dominant characteristic of the major operation. CMOCs can be established at all levels of command. Hence, more than one CMOC may exist in an AO, particularly large urban areas. CMOCs may be organized in various ways and include representatives from as many agencies as required to facilitate the flow of information among all concerned parties. Commanders must still ensure that force protection and OPSEC

requirements are not compromised. Effective CMOCs can serve as clearinghouses for the receipt and validation of all civilian requests for support, can aid in prioritizing efforts and eliminating redundancy, can decrease the potential for inappropriate displays of wealth by one or more of the participating organizations, and, most importantly, can reduce wasting the urban commander’s scarce resources.

LIAISON OFFICERS

5-102. LNOs—sufficiently experienced and adequately trained in liaison duties and functions—are necessary to deal with the other agencies that have interests in the urban area. Army LNOs work with the lead agency or other organizations (including local civilian agencies such as police) that the commander has identified as critical to mission success. Together they work to rapidly establish unity of effort and maintain coordination, often before a CMOC is established. The additional coordination afforded by the physical presence of LNOs within these organizations may be required even after the CMOC is fully functional. When commanders lack enough LNOs to meet requirements, they should prioritize and often assign a single LNO to several organizations. That LNO will then share his time and presence to those organizations based on the situation and his commander’s guidance.

COMMANDER’S PERSONAL INVOLVEMENT

5-103. Overall, establishing a close relationship with other agencies and the urban civilian population will often be a major, positive factor in successful mission accomplishment, particularly in urban stability operations. Despite internally established command and control relationships, commanders that develop a direct and personal relationship with the leaders and staff of other agencies can often avoid conflict, win support, foster trust, and help eliminate the “us versus them” mentality that can frustrate cooperation among Army forces and civilian organizations.

5-26

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Chapter 6

Foundations for Urban Operations

Utilities such as electricity and water are as much weapons of war as rifles, artillery pieces or fighter aircraft. . . . In the case of Manila, where there was a noncombatant, civilian population of one million in place, it was the attacker’s aim to capture the utilities which the defender planned to destroy.

The Battle for Manila

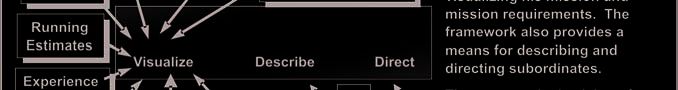

Commanders conducting major urban operations (UO) use their ability to visualize

how doctrine and military capabilities are applied within the context of the urban

environment. An operational framework is the basic foundation for this visualization.

In turn, this visualization forms the basis of operational design and decision making.

To accurately visualize, describe, and direct the conduct of UO, commanders and

their staffs must understand the basic fundamentals applicable to most UO.

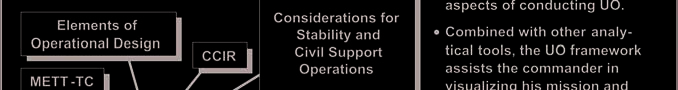

URBAN OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK

6-1. Army leaders who have an urban area in their area of operations (AO) or are assigned missions in an urban area follow an urban operational framework. They identify the portion of the urban area essential to mission success, shape the area, precisely mass the effects of combat power to rapidly dominate the area, protect and strengthen initial gains without losing momentum, and then transition control of the area to another agency. This framework divides into five essential components: understand, shape, engage, consolidate, and transition. These five components provide a means for conceptualizing the application of Army combat power and capabilities in the urban environment.

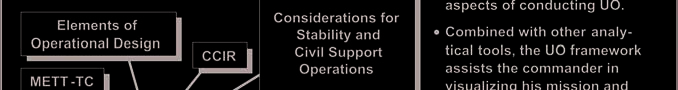

6-2. The urban operational framework assists commanders in visualizing urban operations. This framework is simply an aid to the commander. It is not sequential, nor is it a planner’s tool for phasing an operation. Commanders should combine the urban operational framework with—

z

The principles of war.

z

The tenets of Army operations.

z

The components of operational design.

z

Considerations for stability operations and civil support operations.

z

Sustainment characteristics.

z

Running estimates.

z

Commander’s critical information requirements (CCIR).

z

Each commander’s experience.

The framework contributes to the visualizing, describing, and directing aspects of leadership that make commanders the catalysts of the operations process (see Figure 6-1). In the same manner, the urban operational framework contributes to the overall operations process (see FM 3-0).

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

6-1

Chapter 6

Figure 6-1. The urban operational framework and battle command

UNDERSTAND

6-3. Understanding requires continuous assessment—throughout planning, preparation, and execution—

of the current situation and progress of an operation, and the evaluation of it against measures of effectiveness to make decisions and adjustments. Commanders use visualization, staff officers use running estimates, and all use the intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB) process to assess and understand the urban environment. Commanders and staffs begin to understand by observing and then collecting information about the situation. They observe and learn about the urban environment (terrain, society, and infrastructure), and other factors of METT-TC—mission, enemy, weather, troops and support available, and time available. They use intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance means; information systems (INFOSYS); and reports from other headquarters, services, organizations, and agencies. Then they orient themselves to the situation and achieve situational understanding based on a common operational picture (COP) and continuously updated CCIR. Largely, the ability to rapidly and accurately achieve a holistic understanding of the urban environment contributes to the commanders’ abilities to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative during UO.

Disproportionately Critical

6-4. The Army operations process requires continuous assessment and understanding; it precedes and guides every activity. In UO, however, in-depth understanding is disproportionately critical for several reasons. First, each urban environment is unique. Other environments can be studied and their characteristics quantified in a general manner with accuracy. This is fundamentally not true of different urban areas. The characteristics and experience in one urban area often have limited value and application to an urban area elsewhere. This characteristic sets UO apart from operations in other environments.

Extremely Dynamic

6-5. The urban environment is also extremely dynamic. Either deliberate destruction or collateral damage can quickly alter physical aspects of the urban environment. The human aspect is even more dynamic and potentially volatile. A friendly civil population, for example, can become hostile almost instantaneously.

6-2

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Foundations for Urban Operations

These dynamics (combined with initial difficulty of understanding and describing this unique environment) make it difficult for commanders and staffs to initially develop and maintain a COP and establish situational understanding. Furthermore, public reaction to media coverage of the urban operation and political changes influence national security strategy and objectives. Such changes can affect the basic nature of an operation, especially after it has commenced. Anticipating these potential effects and developing appropriate branches and sequels based on an accurate understanding often determines how quickly commanders can achieve the desired end state.

Risk Assessment

6-6. As in any environment, UO pose both tactical and accident risks. However, the level of uncertainty, ambiguity, and friction can often be higher than that of many other environments. Such challenges increase the probability and severity of a potential loss due to the presence of the enemy, a hostile civilian group, or some other hazardous condition within the urban environment (see Determining the Necessity of Urban Operations in Chapter 5). Therefore, commanders must—

z

Identify, assess, and understand hazards that may be encountered in executing their missions.

z

Develop and implement clear and practical control measures to eliminate unnecessary risk.

z

Continuously supervise and assess to ensure measures are properly understood, executed, and remain appropriate as the situation changes.

6-7. Risk decisions are commanders’ business. However, staffs, subordinate leaders, and even individual Soldiers must also understand the risk management process and continuously look for hazards at their level or within their area of expertise. Any risks identified (with recommended risk reduction measures) must be quickly elevated to the appropriate level within the chain of command (see FM 3-100.12 and FM 5-19).

Complex and Resource Intensive

6-8. The urban environment is the most complex of all the environments in which the Army conducts operations. It is often comprised of a diverse civil population and complex, ill-defined physical components. A sophisticated structure of functional, social, cultural, economic, political, and informational institutions unites it. Thus, the analysis to understand the environment is also complex and time and resource intensive. The nuances of the urban environment can take years to uncover. Hence, constant analysis of the environment requires greater command attention and resources. Accurately understanding the environment is a prerequisite to shaping it, and both understanding and shaping activities are crucial to effectively engage the elements of the urban environment critical to success.

SHAPE

6-9. Shaping operations, part of all Army operations, are essential to successful UO. They set the conditions for decisive operations at the tactical level in the urban area. Rapid action, minimum friendly casualties, and acceptable collateral damage distinguish this success when the AO is properly shaped.

Failure to adequately shape the urban AO creates unacceptable risk. The commander of a major urban operation has several resources with which to begin shaping the AO. Important capabilities include—

z

Fires.

z

Information operations.

z

Special operations capabilities.

z

The maneuver of major subordinate units.

6-10. Critical urban shaping operations may include actions taken to achieve or prevent isolation, understand the environment, maintain freedom of action, protect the force, develop cooperative relationships with the urban population, and train Army forces for sustained UO.

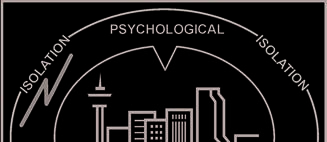

Isolation

6-11. Isolation of an urban environment is often the most critical component of shaping operations.

Commanders who’s AO includes operationally significant urban areas often conduct many shaping 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

6-3

Chapter 6

operations to isolate, or prevent isolation of, those areas from other parts of the AO. Likewise, commanders operating in the urban area focus on isolating decisive points and objectives in the urban area or averting isolation of points that are critical to maintaining their own freedom of action. Isolation is usually the key shaping action that affects UO. It applies across full spectrum operations. Most successful UO have effectively isolated the urban area. Failure to do so often contributed to difficult or failed UO. In fact, the relationship between successful isolation and successful UO is

so great that the threat often opposes external isolation actions

more strongly than operations executed in the urban area (or

critical areas within). In some situations, the success of isolation

efforts has been decisive. This occurs when the isolation of the

urban area compels a defending enemy to withdraw or to

surrender before beginning or completing decisive operations. In

UO that are opposed, Army forces attempt to isolate the threat

three ways: physically, electronically, and, as a resultant

combination of these first two, psychologically (see Figure 6-2).

Figure 6-2. Urban isolation

Physical Isolation

6-12. In offensive UO, physical isolation keeps the threat from receiving information, supplies, and reinforcement while preventing him from withdrawing or breaking out. Conversely, a defending Army force attempts to avoid its own physical isolation. Simultaneously, this force conducts operations to isolate the threat outside, as they enter, or at selected locations in the urban area. Physical isolation can occur at all levels. In many situations, the commander of a major combat operation may attempt to isolate the entire urban area and all enemy forces defending or attacking it. At the tactical level, forces isolate and attack individual decisive points often using a cordon technique. In stability operations, physical isolation may be more subtly focused on isolating less obvious decisive points, such as a hostile civilian group’s individual leaders. In many operations, isolation may be temporary and synchronized to facilitate a decisive operation elsewhere. To effectively isolate an urban area, air, space, and sea forces are often necessary additions to the capabilities of ground forces.

Electronic Isolation

6-13. Electronic isolation is achieved through offensive information operations (IO). Electronic warfare (particularly two of its components: electronic warfare support and electronic attack) and computer network attack are critical to electronic isolation (see FM 3-13 and the Information Operations discussion in Chapter 5). At the operational level, offensive IO aims to quickly and effectively control the information flow into and out of an urban area. This isolation separates the threat’s command and control (C2) system in the urban area from its operational and strategic leadership outside the urban area. Offensive IO also focuses on preventing the threat from communicating with civilians through television, radio, telephone, and computer systems. At the tactical level, IO aim to isolate the threat’s combat capability from its C2 and leadership within the urban area, thus preventing unity of effort within the urban area. Defensive IO can prevent isolation of friendly forces defending in an urban area.

Psychological Isolation

6-14. Psychological isolation is a function of physical actions, electronic warfare, and other forms of IO, especially military deception and psychological operations. Psychological isolation denies the threat political and military allies. It separates the enemy or hostile civilian group from the friendly population, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) operating in the urban area, and from political leaders who may consider supporting Army forces. Psychological isolation destroys the morale of individual enemy soldiers or hostile civilians. It creates a feeling of isolation and hopelessness in the mind of the