Urban Offensive Operations

At dawn on 5 February, 2-12th Cavalry was established 5 kilometers west of Hue.

The battalion soon observed enemy forces and supplies moving toward Hue. From

its high ground position, the battalion directed artillery and air strikes against the NVA forces. By its bold move to bypass the 5th NVA Regiment, the battalion now held

excellent position to direct fires on the primary NVA supply line into Hue. These fires were the first step toward isolating the NVA in Hue.

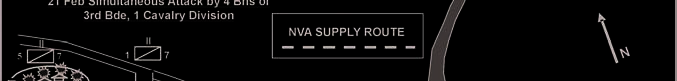

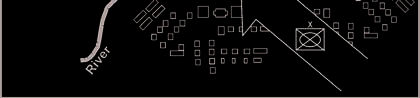

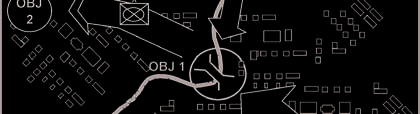

The fires controlled by the 2-12th Cavalry shut down the NVA LOCs into Hue during

the daytime. However, under the cover of darkness supplies and reinforcements

were still entering the city (see figure 7-15). It became apparent that the isolation of the NVA in Hue would require the capture of Thong La Chu. The problem facing

American forces was concentrating combat power against the NVA. All U.S. units at

this time were actively engaged against the numerous NVA attacks that constituted

the NVA’s 31 January Tet Offensive.

Figure 7-15. Subsequent attack to isolate Hue

The first additional American unit was not available until 12 February when the 5 7th Cavalry attacked Thong Que Chu much like the 2-12th Cavalry had attacked

previously. The 5-7th Cavalry had even less success against the alert 5th NVA. The

5-7th Cavalry was forced to occupy defensive positions in Thon Lieu Coc Thuong

and await the build up of combat power before it could continue to attack. In the

interval, 2-12th Cavalry had moved off the high ground and captured the hamlet of

Thon Bon Tri, south of the 5th NVA Regiment.

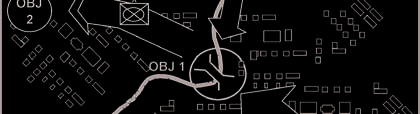

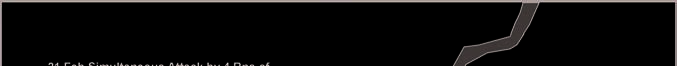

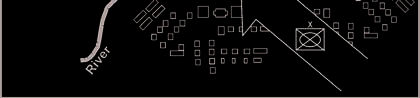

On 21 February, the 1st Cavalry Division had moved enough resources to the area to

launch an effective attack to isolate Hue (see figure 7-16). In addition to the 5-7th and 2-12th Cavalry, the 1-7th Cavalry arrived in the AO and the 2-501st Airborne

Infantry of the 101st Airborne Division was attached. On 21 February, after a

combined artillery, air, and naval gunfire bombardment, the four battalions attacked the Thon La Chu stronghold. Elements of the 5th NVA Regiment were either

destroyed in place or fled northeast. The next day resistance in Hue was noticeably

lighter. U.S. Marine and ARVN units began the last phase of fighting to recapture the Imperial Palace. On 26 February, the North Vietnamese flag was removed from the

Citadel and the ARVN I Corps declared the city secured.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-19

Chapter 7

Figure 7-16. Final attack to isolate Hue

The actions of the 1st Cavalry Division forces northwest of Hue demonstrated the

importance and the difficulty of isolating an enemy fighting in an urban area. Isolating Hue was difficult not only because of the dispersion and surprise with which the Tet Offensive caught U.S. forces, but also because of the tenacity of the NVA. At least

one-third of the combat power of the NVA in the Hue AO was focused on maintaining

access to the city.

Although only one aspect of this urban battle, Hue’s isolation had an immediate and

important, if not decisive, impact on operations. It not only resulted in restriction and then elimination of supplies and reinforcements, but it also immediately impacted the conduct of the defending NVA forces. Isolation caused an immediate drop in NVA

morale and changed the nature of the defense. Once the enemy was isolated from

external support and retreat, the objective of the NVA in the city changed from

defending to avoiding destruction and attempting to infiltrate out of the city.

Civilian Reactions

7-63. Commanders must also consider the potential effects on and reactions and perceptions of the population living in the urban areas that they choose to isolate and bypass—either as a direct effect or as a response of the threat force being isolated. Isolation to reduce the threat’s ability to sustain itself will likely have similar (and worse) effects on the civilian population remaining in the isolated area. (If food and water are in short supply, threat forces may take from noncombatants to satisfy their needs, leaving civilians to starve.) Isolation may also create a collapse of civilian authority within an urban area as it becomes apparent that the military arm of their government is suffering defeat. Due to their isolation, elements of the population may completely usurp the governmental and administrative functions of the former regime and establish their own local control, or the population may lapse into lawlessness.

Returning later, Army commanders may find that these self-governing residents are proud of their accomplishments and, in some instances, less willing to allow Army forces to assume control since they may be perceived as having done nothing to earn that privilege. Alternatively, as witnessed in some urban areas during OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM in 2003, a power vacuum may lead to intra-urban conflicts among rival factions coupled with general public disorder, looting, and destruction of the infrastructure (see also the discussion of Competing Power Structures in Chapter 3).

7-20

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Offensive Operations

Direct Action by Special Operations Forces

7-64. Although SOF in urban offensive operations will likely conduct essential reconnaissance, they also have a direct action capability to shape the offensive operation (see figure 7-17). Special Forces and Rangers can use direct action capabilities to attack targets to help isolate the urban area or to directly support decisive actions subsequently or simultaneously executed by conventional forces. Successful attacks against urban infrastructure, such as transportation or communications centers, further the area’s physical and electronic isolation. Direct action

against command centers, logistics bases, and air

defense assets can contribute to the success of

conventional attacks by destroying or disrupting key

threat capabilities. Direct action can also secure key

targets such as airports, power stations, and

television stations necessary for subsequent

operations. Direct action by Special Forces and

Rangers in these operations can help achieve

precision and reduce potential damage to the target or

noncombatant casualties.

Figure 7-17. Coordination of SOF and

conventional capabilities

Information Operations

7-65. Regardless of how Army forces physically isolate the urban area, they combine physical isolation with offensive IO to electronically isolate the threat and undermine his morale. Electronic isolation will cut off communications between forces in the urban area from their higher command to deny both from knowing the other’s status. IO combined with isolation may persuade the threat’s higher command or leadership that its forces located in the urban area are defeated. Thus, the command or leadership’s intentions to break through to the besieged threat forces may be affected. PSYOP can undermine the morale of the threat in the area and reinforce electronic isolation and perceptions of abandonment. IO can be used to reduce any loyalty the civil population may have to the threat. IO can also ensure that civilians have the information that minimizes their exposure to combat and, as a result, overall noncombatant casualties. In addition, IO aim to deceive the threat regarding the time and place of Army force operations and intentions.

Detailed Leader Reconnaissance

7-66. Army commanders must clearly see the urban environment to understand the challenges facing their brigades, battalions, companies, platoons, and squads. Urban terrain can be deceptive until viewed from the soldier’s perspective. Commanders are responsible to intimately know the conditions to allocate resources effectively to subordinate units. Often, particularly at battalion level and above, commanders will not be able to command and control dispersed forces from positions forward, but be forced by the terrain to rely on semifixed command posts. Detailed leader reconnaissance of the AO by commanders, their staff, and their subordinates before the mission can compensate for this challenge. This reconnaissance will give commanders a personal feel for the challenges of the terrain and will facilitate more accurate planning and better decision making during operations.

Mission Orders

Often what seems to be the correct decision at one level of command may be otherwise at other echelons. It is essential that leaders consider not only the perspective of their own 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-21

Chapter 7

unit, but that of other relevant participants as well, to include the enemy, adjacent friendly units, higher headquarters, and noncombatants.

Lesson Number 18

An Attack on Duffer’s Downtown

7-67. Before contact, commanders can mitigate some terrain challenges to effective C2 using mission orders. Subordinates have mission orders to take advantage of opportunities before C2 systems can adversely impact the environment. To see the battle and provide effective and timely direction, tactical leaders will follow closely behind units as they assault buildings, floors, and rooms. Thus, only the most mobile INFOSYS can accompany tactical leaders into combat, and they will suffer the degrading effects of the environment. Mission orders permit rapid and decisive execution without commanders intervening at battalion level and above. Higher-level commanders can facilitate mission orders through their subordinates by articulating their desired end state, clearly stating their intent, and building flexibility into the overall plan.

Effective Task Organization

7-68. Commanders can shape urban offensive operations through effective and innovative task organization. Combined arms, often starting with an infantry base, are essential to success and may be the Army’s asymmetric means of defeating an urban threat. Urban attacks will quickly break down into noncontiguous firefights between small units. To achieve the tactical agility for mission success in this nonlinear environment, many Army capabilities are task organized down to the company, platoon, and squad levels. Infantry provides the decisive capability to enter buildings and other structures to ensure threat destruction. Tanks, gun systems, and fighting vehicles provide additional speed and mobility, direct firepower, and protection. Combat engineers provide specialized breaching and reconnaissance capability.

Field artillery provides the indirect (and if necessary, direct) firepower. Such mobility and firepower create the conditions necessary for the dismounted infantry to close with and destroy a covered threat in an urban defense. When a threat skillfully uses the urban area to limit ground maneuver, vertical envelopment or aerial attack using precision-guided munitions from Army aviation may circumvent his defenses and achieve necessary effects. Generally, ground systems used within the urban area will not be able to operate independently from dismounted infantry. The infantry will be required to protect armor and mechanized systems from close antiarmor weapons, particularly when those weapons are in well-prepared positions located throughout the urban area but especially on rooftops and in basements.

7-69. In urban offensive operations, direct fire support can be critical. Armor vehicle munitions types do not always achieve decisive effects against some urban structures. In some cases, field artillery high explosive munitions work better than armor for direct fire support of infantry. Large caliber (105 or 155mm) high explosives directly fired at a structure often produce a more severe shock effect than tank and fighting vehicle cannon and machine guns produce. Artillery is also able to achieve higher elevation than armor and engage threats located at greater heights.

7-70. However, commanders must view artillery as not just a weapon but a weapon system. As such, artillery should normally be placed under tactical control (TACON) of maneuver commanders, such as a platoon of three guns TACON to a company or a battery to a battalion, not just one gun to a company or other maneuver unit. Self-propelled artillery has some of the mobility characteristics of armor; however, it provides minimal ballistic protection from fragmentation for the crew. Although these systems seem formidable, they provide less crew protection than a Bradley fighting vehicle, for example, and contain large amounts of onboard ammunition and propellant. They are susceptible to catastrophic destruction by heavy automatic weapons, light cannon, and antitank fire. Therefore, infantry units must carefully secure and protect these systems (even more so than armored vehicles) when employed in urban offensive operations, particularly when forward in the direct fire role.

Creative Task Organization: Using Artillery in the Direct Fire Role

Task organizing artillery to permit its use in a direct fire role demonstrates the

innovative task organization required for urban operations. The following provides

7-22

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Offensive Operations

three historical examples of task organizing and using field artillery for a direct fire role.

————————————————————

In 1944, U.S. Army units of the 1st Infantry Division were assigned to attack and

seize the German city of Aachen. The city’s internal defense included bunkers

designed to serve as air raid shelters. These positions, buildings of stone, seemed

impervious to direct fire tank weapons, demolitions, and small arms. To reduce the

positions, the 1st Infantry Division relied on the artillery’s direct fire.

Field artillery used this way had physical and psychological effects on the defenders.

The 26th Regimental Combat Team’s history of the battle describes the German

reaction to the artillery pieces:

The chief shock to the defenders, Colonel Wilck (Aachen defense commander) said, came from the self-propelled 155s and tanks. The colonel spoke with considerable consternation of the 155mm self-propelled rifles. A shell from one of the guns, he said, pierced three houses completely before exploding and wrecking a fourth.

The 26th Infantry Regiment also described how the artillery, one piece attached to

each assaulting infantry battalion, helped the infantry to penetrate buildings.

With solid blocks of buildings comprising most of the city, there wasn’t any easy way to get at the Germans in the buildings. The eight-inch gun solved the problem.

Beginning on the eastern outskirts the gun would plow a round into the side of the built up block of buildings at about ground level. One shell would usually open an entrance into the first tier of floors, i.e. the first building. Then several more shells were fired through the first hole. Thus a tunnel would be rapidly made all the way to the next cross street. Soldiers could then rush the newly formed entrance, clear the upper floors with hand grenades and rifles and then move on to the next building to repeat the process. When a block or square, was thus completely cleared of

Germans—soldiers, skulkers, or even snipers—the next square was treated in the

same way, working forward square by square, right and left, thereby avoiding nearly all exposure in the streets.

————————————————————

In 1982, Israeli forces invaded southern Lebanon to destroy base camps of the

Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). This operation involved significant fighting in urban areas including major operations in Beirut. Artillery, firing in a direct fire role, played a major part of the tactical solution. Artillery was particularly effective in the 33-day siege of Beirut. During this siege, Israeli forces used artillery in its traditional role as well as in the direct fire role.

The Israeli army was committed to a policy of disproportionate response during the

Beirut siege. When fired on with small arms, crew-served weapons, tanks, or indirect artillery, the Israeli forces responded with intense, high-caliber direct and indirect fire from tanks and artillery positioned around the city. Many firing positions were on

heights to the south and southwest that dominated much of the city. These positions

had almost unrestricted fields of view. Israeli artillery fired from these positions directly into high-rise buildings concealing PLO gunners and snipers. The artillery, using direct fire, destroyed entire floors, collapsed floors on top of each other, and completely removed some upper floors. Such a response, as in Aachen in 1944, had

as much a psychological impact as it did a physical impact on the PLO defenders.

————————————————————

In the early hours of 20 December 1989, the United States launched OPERATION

JUST CAUSE. One of this operation’s objectives was removing the Panamanian

dictator, Manuel Noriega. U.S. forces carefully planned using all fires before the

operation to minimize casualties and collateral damage. Part of this detailed fire

planning called for applying artillery in a direct fire role.

The Panamanian Defense Force’s (PDF) 5th Rifle Company based at Fort Amador

was one of the key objectives of U.S. forces at the start of hostilities. This unit was high priority because it was the closest PDF unit to Noriega’s headquarters, the

Comandancia. U.S. forces expected the 500-man company to react first to

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

7-23

Chapter 7

OPERATION JUST CAUSE by reinforcing the defense of the Comandancia. It also

posed a threat to U.S. military dependents housed at Fort Amador.

To quickly neutralize this force, the United States assembled a three-company force

composed of A, B, and headquarters elements of 1-508th Infantry (Airborne),

supported by 105mm towed howitzers of 320th Field Artillery and M113 armored

personnel carriers. The howitzers and the personnel carriers were covertly pre-

positioned at the fort. At approximately 0100, helicopters transported the two

airborne rifle companies into position. The howitzers then suppressed any personnel

in the PDF-controlled buildings on Fort Amador while demonstrating the firepower of

the U.S. task force. They used direct fire into the PDF barracks. The impact of the

105mm high explosives and .50-caliber fire from the M113s convinced the PDF

infantry to give up after token resistance. Following the direct fire, U.S. infantry assaulted and cleared the dozen PDF buildings, finding that most occupants had fled

or surrendered. For more details of OPERATION JUST CAUSE, see Applying the

Urban Operational Framework: Panama in Chapter 5.

————————————————————

The three examples cited indicate the importance of the situation-dependent and

innovative task organization of artillery and its use in the direct fire role. Using artillery helps overcome some challenges of offensive operations in the urban environment,

and it has an important psychological effect on a defending threat. Such task

organization takes a traditional tool of a higher-level tactical commander and uses it to directly influence the company-level battle. This philosophy of task organization can be applied to other types of forces—not just artillery. PSYOP teams, interpreters, CA specialists, armor, engineers, and reconnaissance teams may require task

organization different from traditional organization. The compartmented urban

environment drives the requirements for these assets lower in the tactical scheme

than in open operations. Consequently, commanders must understand and account

for more of these assets for UO than for operations in less restrictive environments.

7-71. Army aviation may also be inventively task organized. It can support urban operations with lift, attack, and reconnaissance capabilities. Tactical commanders down to company may use all these capabilities to positively influence ground close combat. Army attack and reconnaissance aircraft can provide flank security for attacking ground forces. Attack aircraft may also provide direct fire support to individual platoons or squads. Lift may move entire battalions as part of brigade operations, or it may move single squads to a position of advantage (such as a roof) as part of a small unit assault. Army aviation can assist with C2 by providing airborne retransmission capability, airborne command posts, and the confirmed status and position of friendly forces. However, Army aviation is a limited and high-value asset; commanders should review its use in innovative task organizations. It is particularly vulnerable to urban air defense threats unless used over terrain secured by ground forces. From these positions, aircraft can use enhanced sensors to conduct reconnaissance and use precision weapons with standoff capability.

Shaping Attacks

7-72. In a large urban area, the defending threat cannot be strong everywhere. Shaping operations can also take the form of attacks against vulnerable positions to force the threat to maneuver and redeploy his forces in the urban area. This prevents him from merely defending from prepared positions. Forcing the threat to move negates many of the defensive advantages of urban terrain, confirms his dispositions, exposes vulnerable flanks, and permits target acquisition and engagement with precision standoff fires.

7-73. A critical shaping operation in urban offensive operations is usually an initial attack to seize a foothold. Once Army forces establish this foothold, they accrue some of the defensive advantages of urban terrain. From this protected location, Army forces continue offensive operations and have a position of advantage against neighboring threat defensive positions.

7-24

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Urban Offensive Operations

ENGAGE

7-74. Commanders may employ several methods to decisively engage elements of the urban area during offensive operations. These include—

z

Rapid maneuver.

z

Appropriate use of SOF.

z

Precise application of fires and effects.

z

Proper balance of speed and security.

7-75. None is unique to UO. Their effective execution, however, allows Army commanders to dominate in this challenging environment by effectively using resources with the least amount of collateral damage.

Overall, decisive engagement results from urban offensive operations when forces achieve the objective of the assigned mission and establish preeminent control over the necessary terrain, population, and infrastructure. Largely, the Army commander’s ability to engage is based on superior situational understanding and the correct application of unit strengths to the challenges found in the urban environment.

Rapid and Bold Maneuver

7-76. Commanders of major operations may

have or create the opportunity to seize an

urban area with rapid and bold maneuver.

Such maneuver requires striking while the

area remains relatively undefended—

essentially preempting an effective defense.

This opportunity occurs when the urban area is

well to the rear of defending threat forces or

before the onset of hostilities. Under such

conditions, an attack requires striking deep

behind threat forces or striking quickly with

little time for the threat to make deliberate

preparations. Attacks under such conditions

may entail significant risk; however, the

potential benefit of audacious offensive

US Army Photo

operations may be well worth possible losses.

Three potential ways to accomplish such attacks (and their combinations) are:

z

Airborne or air assault.

z

Amphibious assault.

z

Rapid penetration followed by an exceptionally aggressive exploitation, for example, a heavy force using shock, armor protection, and mobility.

7-77. Commanders should analyze all potential urban operations to seek an opportunity or advantage to apply rapid and bold operational maneuver to the task. Using operational maneuver to avoid urban combat against an established threat defense potentially marks a significant operational achievement and can have decisive strategic consequences. Just influencing the threat’s morale can positively affect all future operations. However, commanders must evaluate the challenges of such a course of action. These challenges may include—

z

Sustaining the operation.

z

Avoiding isolation and piecemeal destruction.

z

Successfully conducting shaping attacks.

z