26 October 2006

FM 3-06

A-3

Appendix A

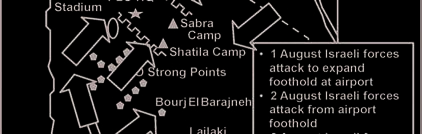

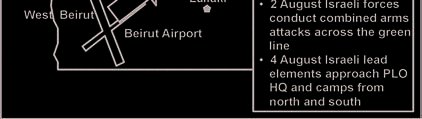

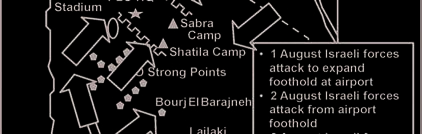

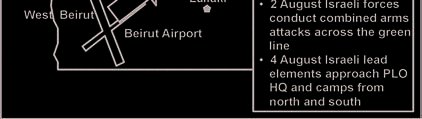

A-14. The Israeli bombardment stopped on 31 July.

However, on 1 August the IDF launched its first

major ground attack, successfully seizing Beirut

airport in the south (see Figure A-5). Israeli armored

forces began massing on 2 August along the green

line, simultaneously continuing the attack from the

south to the outskirts of the Palestinian positions at

Ouzai. On 3 August, the Israeli forces continued to

reinforce both their southern attack forces and forces

along the green line to prepare for continuing

offensive operations. On 4 August, the IDF attacked

at four different places. This was the much-

anticipated major Israeli offensive.

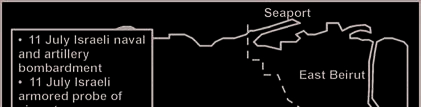

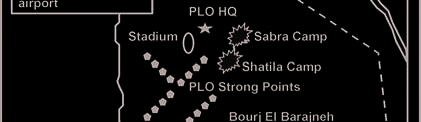

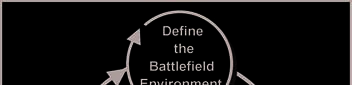

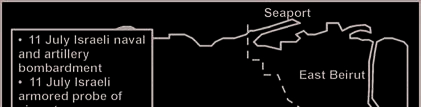

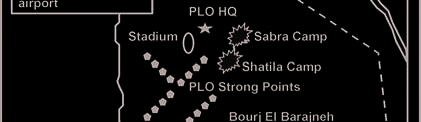

Figure A-4. Initial Israeli attack

A-15. The Israeli attack successfully disrupted the coherence of the PLO defense. The southern attack was the most successful: it pushed PLO forces back to their camps of Sabra and Shatila and threatened to overrun PLO headquarters. Along the green line the

IDF attacked across three crossing points. All three

attacks made modest gains against stiff resistance.

For this day’s offensive, the Israelis suffered 19 killed

and 84 wounded, the highest single day total of the

siege, bringing the total to 318 killed. Following the

major attacks on 4 August, Israeli forces paused and,

for four days, consolidated their gains and prepared to

renew the offensive. Skirmishes and sniping

continued, but without significant offensive action.

On 9 August, the IDF renewed air and artillery

attacks for four days. This activity culminated on 12

August with a massive aerial attack that killed over a

hundred and wounded over 400—mostly civilians. A

cease-fire started the next day and lasted until the

PLO evacuated Beirut on 22 August.

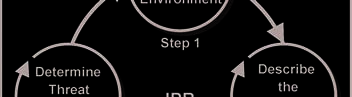

Figure A-5. Final Israeli attack

LESSONS

A-16. The Israeli siege of West Beirut was both a military and a political victory. However, the issue was in doubt until the last week of the siege. Military victory was never in question; the issue in doubt was whether the Israeli government could sustain military operations politically in the face of international and domestic opposition. On the other side, the PLO faced whether they could last militarily until a favorable political end could be negotiated. The answer was that the PLO’s military situation became untenable before the Israeli political situation did.

A-17. This favorable military and political outcome stemmed from the careful balance of applying military force with political negotiation. The Israelis also balanced the type of tactics they employed against the domestic aversion to major friendly casualties and international concern with collateral damage.

PERFORM AGGRESSIVE INFORMATION OPERATIONS

A-18. The PLO devoted considerable resources and much planning on how to use IO to their best advantage. They chose to focus on media information sources as a means of influencing international and domestic opinion.

A-4

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Siege of Beirut: An Illustration of the Fundamentals of Urban Operations

A-19. The PLO’s carefully orchestrated misinformation and control of the media manipulated international sentiment. The major goal of this effort was to grossly exaggerate the claims of civilian casualties, damage, and number of refugees—and this was successfully accomplished. Actual casualties among the civilians were likely half of what the press reported during the battle. The failure of the IDF to present a believable and accurate account of operations to balance PLO efforts put tremendous pressure on the Israeli government to break off the siege. It was the PLO’s primary hope for political victory.

A-20. In contrast to the overall weak performance in IO, the IDF excelled in psychological operations. IDF

psychological operations attacked the morale of the PLO fighter and the Palestinian population. They were designed to wear down the will of the PLO to fight while convincing the PLO that the IDF would go to any extreme to win. Thus defeat was inevitable. The IDF used passive measures, such as leaflet drops and loudspeaker broadcasts. They used naval bombardment to emphasize the totality of the isolation of Beirut.

To maintain high levels of stress, to deny sleep, and to emphasize their combat power, the IDF used constant naval, air, and artillery bombardment. They even employed sonic booms from low-flying aircraft to emphasize the IDF’s dominance. These efforts helped to convince the PLO that the only alternative to negotiation on Israeli terms was complete destruction.

MAINTAIN A CLOSE COMBAT CAPABILITY

A-21. The ground combat during the siege of Beirut demonstrated that the lessons of tactical ground combat learned earlier in the twentieth century were still valid. Small combined arms teams built around infantry, but including armor and engineers, were the key to successful tactical combat. Artillery firing in direct fire support of infantry worked effectively as did the Vulcan air defense system. The Israeli tactical plan was sound. The Israelis attacked from multiple directions, segmented West Beirut into pieces, and then destroyed each individually. The plan’s success strongly influenced the PLO willingness to negotiate.

Tactical patience based on steady though slow progress toward decisive points limited both friendly and noncombatant casualties. In this case, the decisive points were PLO camps, strong points, and the PLO

headquarters.

A-22. The Israeli willingness to execute close combat demonstrated throughout the siege, but especially in the attacks of 4 August, was decisive. Decisive ground combat was used sparingly, was successful and aimed at decisive points, and was timed carefully to impact on achieving the political objectives in negotiations. The PLO had hoped that their elaborate defensive preparations would have made Israeli assaults so costly as to convince the Israelis not to attack. That the Israelis could successfully attack the urban area convinced the PLO leadership that destruction of their forces was inevitable. For this reason they negotiated a cease-fire and a withdrawal on Israeli terms.

AVOID THE ATTRITION APPROACH

A-23. The Israelis carefully focused their attacks on objects that were decisive and would have the greatest impact on the PLO: the known PLO headquarters and refugee centers. Other areas of West Beirut were essentially ignored. For example, the significant Syrian forces in West Beirut were not the focus of Israeli attention even though they had significant combat power. Selectively ignoring portions of the urban area allowed the Israelis to focus their combat power on the PLO and limit both friendly casualties and collateral damage.

CONTROL THE ESSENTIAL AND PRESERVE CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE

A-24. The Israeli siege assured Israeli control of the essential infrastructure of Beirut. The initial Israeli actions secured East Beirut and the city’s water, power, and food supplies. The Israelis also dominated Beirut’s international airport, closed all the sea access, and controlled all routes into and out of the city.

They controlled and preserved all that was critical to operating the city and this put them in a commanding position when negotiating with the PLO.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

A-5

Appendix A

MINIMIZE COLLATERAL DAMAGE

A-25. The Israeli army took extraordinary steps to limit collateral damage, preserve critical infrastructure, and put in place stringent rules of engagement (ROE). They avoided randomly using grenades in house clearing, limited the use of massed artillery fires, and maximized the use of precision weapons. With this effort, the Israelis extensively used Maverick missiles because of their precise laser guidance and small warheads.

A-26. The strict ROE, however, conflicted with operational guidance that mandated that Israeli commanders minimize their own casualties and adhere to a rapid timetable. The nature of the environment made fighting slow. The concern for civilian casualties and damage to infrastructure declined as IDF

casualties rose. They began to bring more field artillery to bear on Palestinian strong points and increasingly employed close air support. This tension underscores the delicate balance that Army commanders will face between minimizing collateral damage and protecting infrastructure while accomplishing the military objective with the least expenditure of resources—particularly soldiers. ROE is but one tool among many that a commander may employ to adhere to this UO fundamental.

UNDERSTAND THE HUMAN DIMENSION

A-27. The Israelis had a noteworthy (although imperfect and at times flawed) ability to understand the human dimension during their operations against the PLO in Beirut. This was the result of two circumstances. First, the PLO was a threat with which the Israeli forces were familiar after literally decades of conflict. Second, through a close alliance and cooperation with Lebanese militia, the Israelis understood a great deal regarding the attitudes and disposition of the civil population both within and outside Beirut.

SEPARATE NONCOMBATANTS FROM COMBATANTS

A-28. Separating combatants from noncombatants was a difficult but important aspect of the Beirut operation. The Israelis made every effort to positively identify the military nature of all targets. They also operated a free passage system that permitted the passage of all civilians out of the city through Israeli lines. The need to impose cease-fires and open lanes for civilians to escape the fighting slowed IDF

operations considerably. Additionally, Israeli assumptions that civilians in urban combat zones would abandon areas where fighting was taking place were incorrect. In many cases, civilians would try to stay in their homes, leaving only after the battle had begun. In contrast, the PLO tied their military operations closely to the civilian community to make targeting difficult. They also abstained from donning uniforms to make individual targeting difficult.

A-29. Earlier in OPERATION PEACE FOR GALILEE when the IDF attacked PLO forces located in Tyre, Israeli psychological operations convinced 30,000 Lebanese noncombatants to abandon their homes and move to beach locations outside the city. However, the IDF was subsequently unable to provide food, water, clothing, shelter, and sanitation for these displaced civilians. IDF commanders compounded the situation by interfering with the efforts by outside relief agencies to aid the displaced population (for fear that the PLO would somehow benefit). Predictably, many civilians tried to return to the city complicating IDF maneuver and targeting—that which the separation was designed to avoid. IDF commanders learned that, while separation is important, they must also adequately plan and prepare for the subsequent control, health, and welfare of the noncombatants they displace.

RESTORE ESSENTIAL SERVICES

A-30. Since essential services were under Israeli command, and had been since the beginning of the siege, the Israelis had the ability to easily restore these resources to West Beirut as soon as they adopted the cease-fire.

TRANSITION CONTROL

A-31. In the rear areas of the Israeli siege positions, the Israeli army immediately handed over civic and police responsibility to civil authorities. This policy of rapid transition to civil control within Israeli lines A-6

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Siege of Beirut: An Illustration of the Fundamentals of Urban Operations

elevated the requirement for the Israeli army to act as an army of occupation. The Israeli army believed the efficient administration of local government and police and the resulting good will of the population more than compensated for the slightly increased force protection issues and the increased risk of PLO

infiltration.

A-32. Upon the cease-fire agreement, Israeli forces withdrew to predetermined positions. International forces under United Nations (UN) control supervised the evacuation of the PLO and Syrian forces from Beirut. These actions were executed according to a meticulous plan developed by the Israeli negotiators and agreed to by the PLO. Israeli forces did not take over and occupy Beirut as a result of the 1982 siege (an occupation did occur later but as a result of changing situations).

SUMMARY

A-33. The Israeli siege of West Beirut demonstrates many of the most demanding challenges of urban combat. Apart from Israel’s poor understanding of the strategic influence of the media on operations (a lesson that they learned and subsequently applied to future operations), the IDF’s successful siege of Beirut emerged from their clear understanding of national strategic objectives and close coordination of diplomatic efforts with urban military operations. A key part of that synchronization of capabilities was the understanding that the efforts of the IDF would be enhanced if they left an escape option open to the PLO.

This option was the PLO’s supervised evacuation that occurred after the siege. Although the PLO was not physically destroyed, the evacuation without arms and to different host countries effectively shattered the PLO’s military capability. Had Israel insisted on the physical destruction of the PLO in Beirut, the overall operation might have failed because that goal may not have been politically obtainable in view of the costs in casualties, collateral damage, and international opinion.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

A-7

This page intentionally left blank.

Appendix B

An Urban Focus to the Intelligence Preparation of the

Battlefield

Maneuvers that are possible and dispositions that are essential are indelibly written on the ground. Badly off, indeed, is the leader who is unable to read this writing. His lot must inevitably be one of blunder, defeat, and disaster.

Infantry in Battle

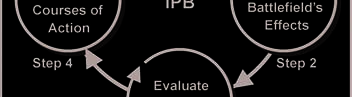

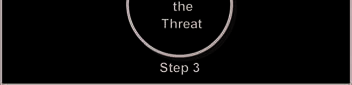

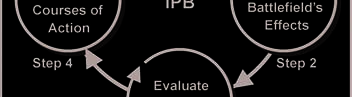

The complexity of the urban environment and increased number of variables (and

their infinite combinations) increases the difficulty of providing timely, relevant, and effective intelligence support to urban operations (UO). Conducted effectively,

however, the intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB) allows commanders to

develop the situational understanding necessary to visualize, describe, and direct

subordinates in successfully accomplishing the mission.

IPB is the systematic process of analyzing

the threat and environment in a specific

geographic area—the area of operations

(AO) and its associated area of interest (see

figure B-1). It provides the basis for

intelligence support to current and future

UO, drives the military decision-making

process, and supports targeting and battle

damage assessment. The procedure (as well

as each of its four steps) is performed contin

uously throughout the planning, preparation,

and execution of an urban operation.

Figure

B-1. The steps of IPB

UNAFFECTED PROCESS

B-1. The IPB process is useful at all echelons and remains constant regardless of the operation or environment. However, an urban focus to IPB stresses some aspects not normally emphasized for IPBs conducted for operations elsewhere. The complex urban mosaic is composed of the societal, cultural, or civil dimension of the urban environment; the overlapping and interdependent nature of the urban infrastructure; and the multidimensional terrain. This mosaic challenges the conduct of an urban-focused IPB. There is potential for full spectrum operations to be executed near-simultaneously as part of a single major operation occurring in one urban area with multiple transitions. Such multiplicity stresses the importance of a thorough, non-stop IPB cycle aggressively led by the commander and executed by the entire staff.

Overall, the art of applying IPB to UO is in properly employing the steps to the specific operational environment. In UO, this translates to analyzing the significant characteristics of the environment, the role that its populace has in threat evaluation, and understanding how these affect the planning and execution of UO. FM 2-01.3 details how to conduct IPB; FM 34-3 has the processes and procedures for producing all-source intelligence. This appendix supplements the information found there; it does not replace it.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

B-1

Appendix B

INCREASED COMPLEXITY

B-2. Uncovering intricate relationships takes time, careful analysis, and constant refinement to determine actual effects on friendly and threat courses of action (COAs). These relationships exist among—

z

Urban population groups.

z

The technical aspects of the infrastructure.

z

The historical, cultural, political, or economic significance of the urban area in relation to surrounding urban and rural areas or the nation as a whole.

z

The physical effects of the natural and man-made terrain.

B-3. A primary goal of any IPB is to accurately predict the threat’s likely COA (step four—which may include political, social, religious, informational, economic, and military actions). Commanders can then develop their own COAs that maximize and apply combat power at decisive points. Understanding the decisive points in the urban operation allows commanders to select objectives that are clearly defined, decisive, and attainable.

Reducing Uncertainty and Its Effects

B-4. Commanders and their staffs may be unfamiliar with the intricacies of the urban environment and more adept at thinking and planning in other environments. Therefore, without detailed situational understanding, commanders may assign missions that their subordinate forces may not be able to achieve. As importantly, commanders and their staffs may miss critical opportunities because they appear overwhelming or impossible (and concede the initiative to the threat). They also may fail to anticipate potential threat COAs afforded by the distinctive urban environment. Commanders may fail to recognize that the least likely threat COA may be the one adopted precisely because it is least likely and, therefore, may be intended to maximize surprise. Misunderstanding the urban environment’s effect on potential friendly and threat COAs may rapidly lead to mission failure and the unnecessary loss of Soldiers’ lives and other resources. A thorough IPB of the urban environment can greatly reduce uncertainty and contribute to mission success.

Training, Experience, and Functional Area Expertise

B-5. Not all information about the urban environment is relevant to the situation and mission—hence the difficulty and the reason for IPB and intelligence analysis. Although it may appear daunting, institutional education, unit training, and experience at conducting intelligence support to UO will improve the ability to rapidly sort through all the potential information to separate the relevant from merely informative. (This applies to any new or difficult task.) The involvement and functional expertise of the entire staff will allow commanders to quickly identify the important elements of the environment affecting their operations.

Fortunately, IPB as part of the entire intelligence process (plan, prepare, collect, process, and produce) is comprehensive enough to manage the seemingly overwhelming amounts of information coming from many sources. Accomplished properly, it allows commanders to recognize opportunities often without complete information.

B-6. As in any operational environment, tension exists between the desire to be methodical and the need to create the tempo necessary to seize, retain, and exploit the initiative necessary for decisive UO. Quickly defining the significant characteristics of the urban environment requiring in-depth evaluation (not only what we need to know but what is possible to know) allows rapid identification of intelligence gaps (what we know versus what we don’t know). Such identification leads to information requirements and will drive the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) plan (how will we get the information we need).

Commanders must carefully consider how to develop focused priority information requirements (PIR) to enable collectors to more easily weed relevant information from the plethora of information. Commanders can then make better decisions and implement them faster than urban threats can react.

B-2

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

An Urban Focus to the Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield

AMPLIFIED IMPORTANCE OF CIVIL (SOCIETAL) CONSIDERATIONS

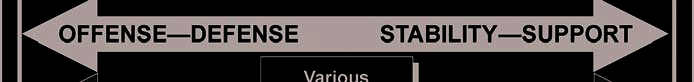

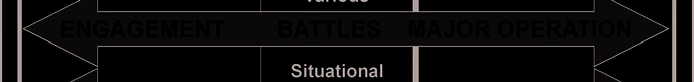

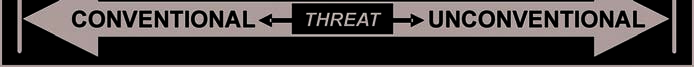

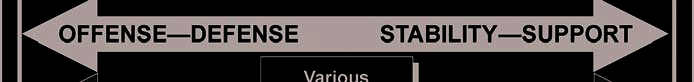

B-7. The Army focuses on warfighting. The experiences in urban operations gained at lower echelons often center on the tactics of urban offensive and defensive operations where the influences of terrain and enemy frequently dominate. At higher echelons, the terrain and enemy are still essential considerations, but the societal component of the urban environment is considered more closely and throughout the operational process. Moreover, the human or civil considerations gain importance in civil support or stability operations regardless of the echelon or level of command. In addition to the echelon and the type of operation, a similar relationship exists between the key elements of the urban environment and other situational factors. These factors can include where the operation lies within the range of operations or the level of war and the conventional or unconventional nature of the opposing threat. Figure B-2 graphically represents the varying significance of these elements to urban IPB. Overall, population effects are significant in how they impact the threat, Army forces, and overall accomplishment of strategic and operational goals.

Figure B-2. Relativity of key urban environment elements

B-8. Describing the battlefield’s effects—step two in IPB—ascribes meaning to the characteristics analyzed. It helps commanders understand how the environment enhances or degrades friendly and threat forces and capabilities. It also helps commanders understand how the environment supports the population.

It also explains how changes in the “normal” urban environment (intentional or unintentional and because of threat or friendly activities) may affect the population. Included in this assessment are matters of perception. At each step of the IPB process, commanders must try to determine the urban society’s perceptions of ongoing activities to ensure Army operations are viewed as intended. Throughout this process, commanders, staffs, and analysts cannot allow their biases—cultural, organizational, personal, or cognitive—to markedly influence or alter their assessment (see FM 34-3). This particularly applies when they analyze the societal aspect of the urban environment. With so many potential groups and varied interests in such a limited area, misperception is always a risk.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

B-3

Appendix B

SIGNIFICANT CHARACTERISTICS

B-9. Urban intelligence analysis must include consideration of the urban environment’s distinguishing attributes—man-made terrain, society, and infrastructure—as well as the underlying natural terrain (to include weather) and the threat. Because the urban environment is so complex, it is often useful to break it into categories. Then commanders can understand the intricacies of the environment that may affect their operations and assimilate this information into clear mental images. Commanders can then synthesize these images of the environment with the current status of friendly and threat forces and develop a desired end state. Then they can determine the most decisive sequence of activities that will move their forces from the current state to the end state. Identifying and understanding the environment’s characteristics (from a friendly, threat, and noncombatant perspective) allows commanders to establish and maintain situational understanding. Then they can develop appropriate COAs and rules of engagement that will lead to decisive mission accomplishment.

B-10. Figures B-3, B-4, and B-5 are not intended to be all-encompassing lists of urban characteristics.

Instead, they provide a starting point or outline useful for conducting an urban-focused IPB and analysis that can be modified to fit the specific operational environment and meet the commander’s requirements.

Commanders and staffs can compare the categories presented with those in the civil affairs area study and assessment format found in FM 41-10 and the IPB considerations for stability and civil support operations found in ST 2-91.1.

INTERCONNECTED SYSTEMS

B-11. Since the urban environment comprises an interconnected “system of systems,” considerations among the key elements of the environment will overlap during an urban intelligence analysis. For example, boundaries, regions, or areas relate to a physical location on the ground. Hence, they have urban terrain implications. These boundaries, regions, or areas often stem from some historical, religious, political, administrative, or social aspect that could also be considered a characteristic of the urban society.

Overlaps can also occur in a specific category, such as infrastructure. For instance, dams are a consideration for their potential effects on transportation and distribution (mobility), administration and human services (water supply), and energy (hydroelectric).

B-12. This overlap recognition is a critical concern for commanders and their staffs.