USCENTCOM] will conduct joint/combined military operations in Somalia to secure the major air and sea ports, key installations and food distribution points, to provide open and free passage of relief supplies, provide security for convoys and relief organization operations, and assist UN/[nongovernmental organizations] in providing humanitarian relief under UN auspices. Upon establishing a secure environment for uninterrupted relief operations, [Commander, USCENTCOM] terminates and transfers relief

operations to UN peacekeeping forces.

C-6. Mogadishu was the largest port in the country and the focal point of previous humanitarian relief activities of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). It was also the headquarters of the coalition of 20

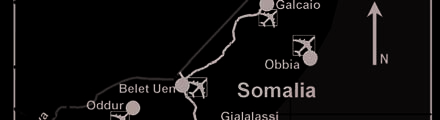

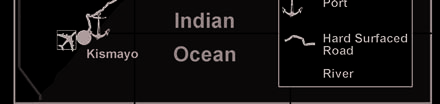

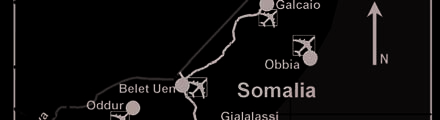

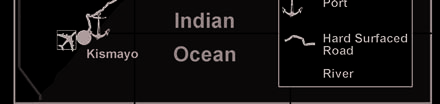

nations and over 30 active humanitarian relief organizations. As such, Mogadishu became the entry point for the operational buildup of the multinational force known as Unified Task Force (UNITAF) and the key logistic hub for all operations in Somalia. UNITAF immediately gained control over the flow of relief supplies into and through Mogadishu and stabilized the conflict among the clans. In less than a month, UNITAF forces expanded control over additional ports and interior airfields. They secured additional distribution sites in other key urban areas in the famine belt to include Baidoa, Baledogle, Gialalassi, Bardera, Belet Uen, Oddur, Marka, and the southern town of Kismayo (see figure C-2). With minimal force, the U.S.-led UNITAF established a secure environment that allowed relief to reach those in need, successfully fulfilling its limited—yet focused—mandate.

C-2

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Operations in Somalia: Applying the Urban Operational Framework to Stability Operations CONTINUED HOPE (UNOSOM II)

C-7. In March 1993, the UN issued UNSCR 814

establishing a permanent peacekeeping force,

UNOSOM II. However, the orderly transition from

UNITAF to UNOSOM II was repeatedly delayed

until May 1993. (The UN Secretary-General urged

the delay so that U.S. forces could effectively

disarm bandits and rival clan factions in Somalia.)

This resolution was significant in two critical

aspects:

z

It explicitly endorsed nation building

with the specific objectives of

rehabilitating the political institutions and

economy of Somalia.

z

It mandated the first ever UN-directed

peace enforcement operation under the

Chapter VII enforcement provisions of

the Charter, including the requirement

for UNOSOM II to disarm the Somali

clans. The creation of a peaceful, secure

environment included the northern region

that had declared independence and had

hereto been mostly ignored.

Figure C-2. Map of Somalia

C-8. These far-reaching objectives exceeded the limited mandate of UNITAF as well as those of any previous UN operation. Somali clan leaders rejected the shift from a peacekeeping operation to a peace enforcement operation. They perceived the UN as having lost its neutral position among rival factions. A more powerful clan leader, General Mohammed Farah Aideed (leader of the Habr Gidr clan), aggressively turned against the UN operation and began a radio and propaganda campaign. This campaign characterized UN soldiers as an occupation force trying to recolonize Somalia.

C-9. The mounting crisis erupted in June 1993. Aideed supporters killed 24 Pakistani soldiers and wounded 57 in an ambush while the soldiers were conducting a short-warning inspection of one of Aideed’s weapons arsenals. UNSCR 837, passed the next day, called for immediately apprehending those responsible and quickly led to a manhunt for Aideed. The United States deployed 400 rangers and other special operations forces (SOF) personnel to aid in capturing Aideed, neutralizing his followers, and assisting the quick reaction force (QRF), composed of 10th Mountain Division units, in maintaining the peace around Mogadishu.

PHASED WITHDRAWAL

C-10. On 3 October 1993, elements of Task Force (TF) Ranger (a force of nearly 100 Rangers and SOF

operators) executed a raid to capture some of Aideed’s closest supporters. Although tactically successful, 2

helicopters were shot down, 75 soldiers were wounded, and 18 soldiers were killed accomplishing the mission. The U.S. deaths, as well as vivid scenes of mutilation to some of the soldiers, increased calls to Congress for withdrawing U.S. forces from Somalia. The President then ordered reinforcements to protect U.S. Forces, Somalia (USFORSOM) as they began a phased withdrawal with a 31 March deadline. The last contingent sailed from Mogadishu on 25 March, ending OPERATION CONTINUED HOPE and the overall U.S. mission in Somalia.

C-11. Although U.S. forces did not carry out the more ambitious UN goals of nation building, they executed their missions successfully, relieving untold suffering through humanitarian assistance with military skill and professionalism. Operations in Somalia occurred under unique circumstances, yet 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

C-3

Appendix C

commanders may glean lessons applicable to future urban stability operations, as well as civil support operations. In any operations, commanders balance changing mission requirements and conditions.

UNDERSTAND

C-12. Although accomplished to varying degrees, U.S. forces failed to adequately assess and understand the urban environment, especially the society. Somali culture stresses the unity of the clan; alliances are made with other clans only when necessary to elicit some gain. Weapons, overt aggressiveness, and an unusual willingness to accept casualties are intrinsic parts of the Somali culture. Women and children are considered part of the clan’s order of battle.

C-13. Early in the planning for OPERATION RESTORE HOPE, U.S. forces did recognize the limited transportation and distribution infrastructure in Mogadishu. The most notable was the limited or poor airport and harbor facilities and its impact on the ability of military forces and organizations to provide relief. Therefore, a naval construction battalion made major improvements in roads, warehouses, and other facilities that allowed more personnel, supplies, and equipment to join the relief effort faster.

UNDERSTANDING THE CLAN (THE HUMAN DIMENSION)

C-14. During OPERATION RESTORE HOPE, the UNITAF worked with the various clan leaders as the only recognized leadership remaining in the country. The UNITAF was under the leadership of LTG

Robert B. Johnston and U.S. Ambassador to Somalia, Robert Oakley. In addition, UNITAF forces also tried to reestablish elements of the Somali National Police—one of the last respected institutions in the country that was not clan-based. This reinstated police force manned checkpoints throughout Mogadishu and provided crowd control at feeding centers. Largely because of this engagement strategy, the UNITAF

succeeded in its missions of stabilizing the security situation and facilitating humanitarian relief. Before its termination, the UNITAF also worked with the 14 major Somali factions to agree to a plan for a transitional or transnational government.

C-15. The UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General, retired U.S. Navy Admiral Jonathon Howe, worked with the UNOSOM II commander, Turkish General Cevik Bir. During OPERATION

CONTINUED HOPE, Howe and General Bir adopted a philosophy and operational strategy dissimilar to their UNITAF predecessors. Instead of engaging the clan leaders, Howe attempted to marginalize and isolate them. Howe initially attempted to ignore Aideed and other clan leaders in an attempt to decrease the warlord’s power. Disregarding the long-established Somali cultural order, the UN felt that, in the interest of creating a representative, democratic Somali government, they would be better served by excluding the clan leadership. This decision ultimately set the stage for strategic failure.

THREAT STRATEGY AND TACTICS

C-16. During OPERATION RESTORE HOPE, U.S. forces also failed to properly analyze and understand their identified threat’s intent and the impact that the urban environment would have on his strategy, operations, and tactics. The UN began to view eliminating Aideed’s influence as a decisive point when creating an environment conducive to long-term conflict resolution. Aideed’s objective, however, remained to consolidate control of the Somali nation under his leadership—his own brand of conflict resolution. He viewed the UN’s operational center of gravity as the well-trained and technologically advanced American military forces, which he could not attack directly. He identified a potential American vulnerability—the inability to accept casualties for an operation not vital to national interests—since most Americans still viewed Somalia as a humanitarian effort. If he could convince the American public that the price for keeping troops in Somalia would be costly, or that their forces were hurting as many Somalis as they were helping, he believed they would withdraw their forces. If U.S. forces left, the powerless UN would leave soon after, allowing Aideed to consolidate Somalia under his leadership.

VULNERABILITY AND RISK ASSESSMENT

C-17. U.S. forces failed to assess, understand, and anticipate that Aideed would adopt this asymmetric approach and attack the American public’s desire to remain involved in Somalia. By drawing U.S. forces C-4

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Operations in Somalia: Applying the Urban Operational Framework to Stability Operations into an urban fight on his home turf in Mogadishu, he could employ guerrilla insurgency tactics and use the urban area’s noncombatants and its confining nature. Such tactics made it difficult for the U.S. forces to employ their technological superiority. If U.S. forces were unwilling to risk harming civilians, his forces could inflict heavy casualties on them, thereby degrading U.S. public support for operations in Somalia. If, on the other hand, the U.S. forces were willing to risk increased civilian casualties to protect themselves, those casualties would likely have the same effect.

C-18. However, an assessment and understanding of the Somali culture and society should have recognized the potential for Aideed’s forces to use women and children as cover and concealment.

Accordingly, the plan should have avoided entering the densely populated Bakara market district with such restrictive rules of engagement. As legitimacy is critical to stability operations, TF Ranger should have been prepared and authorized to employ nonlethal weapons, to include riot control gas, as an alternative to killing civilians or dying themselves.

C-19. U.S. forces also failed to assess and understand the critical vulnerability of their helicopters in an urban environment and the potential impact on their operations. TF Ranger underestimated the threat’s ability to shoot down its helicopters even though they knew Somalis had attempted to use massed rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) fires during earlier raids. (Aideed brought in fundamentalist Islamic soldiers from Sudan, experienced in downing Russian helicopters in Afghanistan, to train his men in RPG firing techniques). In fact, the Somalis had succeeded in shooting down a UH-60 flying at rooftop level at night just one week prior to the battle. Instead, TF Ranger kept their most vulnerable helicopters, the MH-60

Blackhawks, loitering for forty minutes over the target area in an orbit that was well within Somali RPG

range. The more maneuverable AH-6s and MH-6s could have provided the necessary fire support.

Planning should have included a ready ground reaction force, properly task organized, for a downed helicopter and personnel recovery contingency.

C-20. Information operations considerations apply throughout the entire urban operational framework; however, operations security (OPSEC) is critical to both assessment and shaping. OPSEC requires continuous assessment throughout the urban operation particularly as it transitions among the spectrum of operations. As offensive operations grew during OPERATION CONTINUED HOPE, U.S. forces did little to protect essential elements of friendly information. Combined with the vulnerability of U.S. helicopters, Aideed’s followers used U.S. forces’ inattention to OPSEC measures to their advantage. The U.S. base in Mogadishu was open to public view and Somali contractors often moved about freely. Somalis had a clear view both day and night of the soldiers’ billets. Whenever TF Ranger would prepare for a mission, the word rapidly spread through the city. On 3 October 1993, Aideed’s followers immediately knew that aircraft had taken off and, based on their pattern analysis of TF Ranger’s previous raids, RPG teams rushed to the rooftops along the flight paths of the task force’s Blackhawks.

SHAPE

C-21. One of the most critical urban shaping operations is isolation. During OPERATION CONTINUED

HOPE, U.S. forces largely discounted other essential elements of friendly information and did not establish significant public affairs and psychological operations (PSYOP) initiatives. In fact, Army forces lacked a public affairs organization altogether. Consequently, Aideed was not isolated from the support of the Somali people. This failure to shape the perceptions of the civilian populace coupled with the increased use of lethal force (discussed below) allowed Aideed to retain or create a sense of legitimacy and popular support. Ironically, the focus on Aideed helped create a popular figure among the warlords through which many noncompliant, hostile, and even neutral Somalis could rally behind.

C-22. During OPERATION RESTORE HOPE, Aideed conducted propaganda efforts through “Radio Aideed”—his own radio station. UNITAF countered these efforts with radio broadcasts. This technique proved so effective that Aideed called MG Anthony C. Zinni, UNITAF’s director of operations, over to his house on several occasions to complain about UNITAF radio broadcasts. General Zinni responded, “If he didn’t like what we said on the radio station, he ought to think about his radio station and we could mutually agree to lower the rhetoric.” This approach worked.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

C-5

Appendix C

ENGAGE

C-23. The complexity of urban operations requires unity of command to identify and effectively strike the center of gravity with overwhelming combat power or capabilities. Complex command and control relationships will only add to the complexity and inhibit a commander’s ability to dominate and apply available combat power to accomplish assigned objectives. Stability operations as seen in Somalia required commanders to dominate within a supporting role and, throughout, required careful, measured restraint.

UNITY OF COMMAND (EFFORT)

C-24. During OPERATION RESTORE HOPE, UNITAF successfully met unity of command challenges through three innovations. First, they created a civil-military operations center (CMOC) to facilitate unity of effort between NGOs and military forces. Second, UNITAF divided the country into nine humanitarian relief sectors centered on critical urban areas that facilitated both relief distribution and military areas of responsibility. Third, to establish a reasonable span of control, nations that provided less than platoon-sized contingents were placed under the control of the Army, Marine Corps, and Air Force components.

C-25. On the other hand, during OPERATION CONTINUED HOPE, UNOSOM II command and control relationships made unity of command (effort) nearly impossible. The logistic components of USFORSOM

were under UN operational control, while the QRF remained under USCENTCOM’s combatant command—as was TF Ranger. However, the USCENTCOM commander was not in theater. He was not actively involved in planning TF Ranger’s missions or in coordinating and integrating them with his other subordinate commands. It was left to TF Ranger to coordinate with the QRF as needed. Even in TF

Ranger, there were dual chains of command between SOF operators and the Rangers. This underscores the need for close coordination and careful integration of SOF and conventional forces (see Chapter 4). It also emphasizes overall unity of command (or effort when command is not possible) among all forces operating in a single urban environment.

C-26. Following TF Ranger’s 3 October mission, the command structure during OPERATION

CONTINUED HOPE was further complicated with the new JTF-Somalia. This force was designed to protect U.S. forces during the withdrawal from Somalia. JTF-Somalia came under the operational control of USCENTCOM, but fell under the tactical control of USFORSOM. Neither the JTF nor USFORSOM

controlled the naval forces that remained under USCENTCOM’s operational control. However unity of effort (force protection and a rapid, orderly withdrawal) galvanized the command and fostered close coordination and cooperation among the semiautonomous units.

MEASURED RESTRAINT

C-27. During OPERATIONS PROVIDE RELIEF and RESTORE HOPE, U.S. forces dominated within their supporting roles. Their perseverance, adaptability, impartiality, and restraint allowed them to provide a stable, secure environment. Hence, relief organizations could provide the food and medical care necessary to reduce disease, malnourishment, and the overall mortality rate. However, during OPERATION CONTINUED HOPE, U.S. operations became increasingly aggressive under the UN

mandate. However, peace enforcement also requires restraint and impartiality to successfully dominate and achieve political objectives. The increased use of force resulted in increased civilian casualties, which in turn reduced the Somalis’ perception of U.S. legitimacy. As a result, most moderate Somalis began to side with Aideed and his supporters. Many Somalis, without effective information operations to shape their perceptions, felt that it was fine for foreign military forces to intervene in their country to feed the starving and even help establish a peaceful government, but not to purposefully target specific Somali leaders as criminals.

CONSOLIDATE AND TRANSITION

C-28. Across the spectrum of conflict, Army forces must be able to execute full spectrum operations not only sequentially but, as in the case of operations in Somalia, simultaneously. OPERATION PROVIDE

RELIEF began primarily as a stability operation in the form of foreign humanitarian assistance. Later this operation progressed to include peacekeeping (another stability operation), defensive operations to protect C-6

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Operations in Somalia: Applying the Urban Operational Framework to Stability Operations UN forces and relief supplies, and minimum offensive operations. As operations transitioned to OPERATION RESTORE HOPE, it became apparent that while foreign humanitarian assistance was still the principal operation, other operations were necessary. More forceful peacekeeping, show of force, and arms control (all forms of stability operations), and offensive and defensive operations grew increasingly necessary to establish a secure environment for uninterrupted relief operations. In the final phase of U.S.

involvement during OPERATION CONTINUED HOPE, major changes to political objectives caused a major transition in the form of the stability operation to peace enforcement with an even greater increase in the use of force, offensively and defensively, to create a peaceful environment and conduct nation building.

Finally, the TF Ranger raid demonstrated the need to maintain a robust, combined arms force capable of rapidly transitioning from stability operations (primarily peace operations) to combat operations.

SUMMARY

C-29. OPERATIONS PROVIDE RELIEF and RESTORE HOPE were unquestionably successes.

Conversely, during OPERATION CONTINUED HOPE, the 3-4 October battle of Mogadishu (also known as the “Battle of the Black Sea”) was a tactical success leading to an operational failure. TF Ranger succeeded in capturing 24 suspected Aideed supporters to include two of his key lieutenants. Arguably, given the appropriate response at the strategic level, it had the potential to be an operational success. After accompanying Ambassador Oakley to a meeting with Aideed soon after the battle, MG Zinni described Aideed as visibly shaken by the encounter. MG Zinni believed Aideed and his subordinate leadership were tired of the fighting and prepared to negotiate. Unfortunately, the U.S. strategic leadership failed to conduct the shaping actions necessary to inform and convince the American public (and its elected members of Congress) of the necessity of employing American forces to capture Aideed. The President was left with little recourse after the battle of Mogadishu but to avoid further military confrontation.

C-30. Despite this strategic failing, the operational commanders might have avoided the casualties, and any subsequent public and Congressional backlash, had they better communicated among themselves and worked with unity of effort. Recognizing the separate U.S. and UN chains of command, the UN Special Representative, along with the USCENTCOM, USFORSOM, and TF Ranger commanders, should have established the command and control architecture needed. This architecture would have integrated planning and execution for each urban operation conducted. These commanders failed to “operationalize” their plan.

They did not properly link U.S. strategic objectives and concerns to the tactical plan. The TF Ranger mission was a direct operational attempt to obtain a strategic objective in a single tactical action. Yet, they failed to understand the lack of strategic groundwork, the threat’s intent and capabilities, and the overall impact of the urban environment, to include the terrain and society, on the operation. Such an understanding may not have led to such a high-risk course of action but instead to one that de-emphasized military operations and emphasized a political solution that adequately considered the clans’ influence.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

C-7

This page intentionally left blank.

Appendix D

Joint and Multinational Urban Operations

[Joint force commanders] synchronize the actions of air, land, sea, space, and special operations forces to achieve strategic and operational objectives through integrated, joint campaigns and major operations. The goal is to increase the total effectiveness of the joint force, not necessarily to involve all forces or to involve all forces equally.

JP 3-0

As pointed out earlier, Army forces, brigade size and larger, will likely be required to conduct operations in, around, and over large urban areas in support of a joint force commander (JFC). The complexity of many urban environments, particularly those

accessible from the sea, requires unique leveraging and integration of all the

capabilities of U.S. military forces to successfully conduct the operation. This

appendix discusses many of these capabilities; JP 3-06 details joint urban operations.

PURPOSE

D-1. In some situations, a major urban operation is required in an inland area where only Army forces are operating. Army commanders determine if the unique requirements of the urban environment require forming a joint task force (JTF) or, if not, request support by joint capabilities from the higher joint headquarters. Sometimes the nature of the operation is straightforward enough or the urban operation is on a small enough scale that conventional intraservice support relationships are sufficient to meet the mission requirements.

D-2. Most major urban operations (UO), however, require the close cooperation and application of joint service capabilities. A JTF may be designated to closely synchronize the efforts of all services and functions in an urban area designated as a joint operations area (JOA). If a large urban area falls in the context of an even larger ground force area of operations, a JTF dedicated to the urban operation may not be appropriate. These situations still require joint capabilities. In such cases, the responsible JFC designates support relations between major land units and joint functional commands. The major land units can consist of Army forces, Marine Corps forces, or joint forces land component command. The joint functional commands can consist of the joint special operations task force, joint psychological operations task force, or joint civil-military operations task force.

D-3. This appendix describes the roles of other services and joint combatant commands in UO. It provides an understanding that enables Army commanders to recommend when to form a JTF or to request support from the JFC. It also provides information so commanders can better coordinate their efforts with those of the JFC and the commanders of other services or components conducting UO. Lastly, this appendix describes some considerations when conducting UO with multinational forces.

SISTER SERVICE URBAN CAPABILITIES

D-4. Army forces conducting UO rely on other services and functional joint commands for specialized support in the urban environment. These capabilities are requested from and provided through the commanding JFC. Army forces request the assets and capabilities described in this annex through their higher headquarters to the joint command. The JFC determines if the assets will be made available, the appropriate command relationship, and the duration of the support. Army forces prepare to coordinate planning and execution with other services and to exchange liaison officers. These capabilities can greatly 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

D-1

Appendix D

increase the Army’s ability to understand, shape, engage, consolidate, and transition within the context of UO.

AIR FORCE

D-5. Air Force support is an important aspect of the Army force concept for urban operations. Air Force elements have a role to play in UO across the spectrum of operations.

D-6. Air Force intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems contribute significantly to understanding the urban environment. These ISR systems include the E-8 Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (JSTARS) (see figure D-1),

U2 Dragon Lady, RC-135 Rivet Joint, or

RQ-4 Global Hawk and RQ/MQ-1

Predator unmanned aerial systems. Air

Force ISR systems can provide vital data

to help assess threat intentions, threat

dispositions, and an understanding of the

civilian population. These systems also

can downlink raw information in real-time

to Army intelligence processing and

display systems, such as the common

ground station or division tactical

US Air Force Photo

exploitation system.

Figure D-1. USAF E-8 JSTARS platform

D-7. Air interdiction (AI) can be a vital component of shaping the urban operational environment. Often, AI of the avenues of approach into the urban area isolates the threat by diverting, disrupting, delaying, or destroying portions of the threat force before they can be used effectively against Army forces. AI is especially effective in major combat operations where restrictions on airpower are limited and the threat is more likely to be a conventionally equipped enemy.