Multiple echelons collecting from a given area may inadvertently collect from the same sources and thereby give the false impression of independent sources confirming the same data. To help mitigate this possibility, commanders should ensure that all HUMINT sources are properly recorded on intelligence source registers.

z

It may not be timely. The process of identifying and cultivating a source (particularly in an environment where most civilians support threat forces), gathering information, analyzing the information, and providing the intelligence to commanders can be extremely time consuming.

z

Some informants may come from unscrupulous or sordid elements of the urban society and may also have their own agenda. They may attempt to use protection afforded them by their relationship with Army forces to conduct activities (even atrocities) that will compromise 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-11

Chapter 5

political and military objectives. In some cases, a local interpreter’s own agenda may influence his translation. (For example, a local schoolteacher used as a translator may report to the collector that the source believes that repairing schools in their urban area is critical, when actually the source may have said that potable water is most needed.)

Conducting Urban ISR

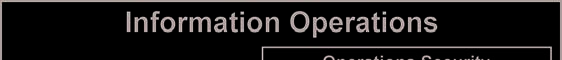

5-45. To be successful, ISR efforts (national to tactical level) are exceptionally comprehensive and synchronized. Moreover, success necessitates the integration of all ISR sources into operational and tactical planning. This requires that ISR assets deploy and execute early, diversify, properly focus, and integrate under a comprehensive ISR plan. Successful ISR also requires flexibility to adapt to the operational and tactical needs of the commander (see Figure 5-2). Commanders must ensure that the appropriate intelligence architecture (including robust links to joint and multinational elements) is established and tested prior to execution of ISR effort.

Early Deployment

5-46. One of the first requirements for effective urban ISR is the early deployment and employment of assets. The complex urban terrain presents a significant challenge. Commanders should consider that ISR

assets will normally take longer to gather data amid the complexity.

5-47. Limited national, strategic, and operational imagery intelli

gence (IMINT) and signals intelligence (SIGINT) capabilities should

be considered and quickly requested. If they are approved, they are

tasked and deployed or repositioned to begin urban ISR operations.

This takes time. Fortunately, spacing the ISR effort over time

permits the analysis of the information or data as it is received. Such

time also permits subsequently refining the ISR effort before all

assets are committed.

5-48. SOF or conventional units will require significantly more time

to execute reconnaissance missions and maintain an acceptable

survivability rate. Urban reconnaissance operations require addi

tional time for stealthy insertion into the urban area. IMINT and

SIGINT capabilities are used to identify possible locations of high-

value targets and corresponding observation positions; this helps

minimize time-consuming and high-risk repositioning in the urban

area. Again, reconnaissance units may require extensive time to

observe from observation positions for indicators of threat activity

and disposition and identify patterns.

Figure 5-2. Urban ISR

considerations

5-49. As conventional combat forces prepare to commit to the urban area, conventional reconnaissance precedes their actions. Conventional reconnaissance will often be a slow and methodical effort. Such forces may need time to reconnoiter the interior of structures for snipers and other small threat teams. They may also need time to deploy and destroy snipers and small delaying elements and to breach harassing obstacles. If necessary, they may need time to mass the combat power necessary to fight through enemy security and continue the reconnaissance.

Diversity

5-50. No single ISR capability can solve the riddle of the urban defense. In order to gain an accurate common operational picture of the complex urban terrain necessary to focus combat power on decisive points, commanders must employ diverse ISR capabilities. These capabilities will each contribute pieces of relevant information to permit identifying operational objectives and leveraging tactical combat power to 5-12

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

achieve those objectives quickly. Higher-level commanders should understand that tactical reconnaissance capabilities alone often cannot provide all the tactical information required for success at lower echelons.

5-51. Using diverse capabilities challenges the threat’s ability to conduct deception and otherwise defeat the friendly ISR effort. A threat that focuses on minimizing his vulnerability to overhead imagery (for example, satellites) may increase his reliance on communications and thus his vulnerability to SIGINT. At the same time, he may decrease his ability to detect the actions of ground reconnaissance units. Conversely, a threat that actively campaigns to detect ground reconnaissance may make himself more vulnerable to SIGINT and IMINT. Moreover, as Army forces enter urban areas, threat activity and susceptibility to SIGNINT often increases.

5-52. Diverse capabilities also facilitate the tactical ISR effort. Tactical reconnaissance units often consist of small dismounted teams and small combined arms teams with a dismounted element and an armor-protected mounted element. Combat engineers with their technical expertise and breaching capability are essential to the combined arms reconnaissance effort. The teams’ movements are synchronized and coordinated with other assets, such as UAS and air cavalry reconnaissance. These teams use several movement techniques including infiltration, with the primary objective of conducting zone reconnaissance along key axes that support brigade and battalion actions against decisive points. To accomplish this mission, reconnaissance reconnoiters the proposed routes and alternate approaches. This supports deception and contingency planning. (Reconnaissance of alternate routes and objectives also applies to aerial reconnaissance; helicopters and UAS are not invisible. They can alert a threat to impending operations.) Infiltration of dismounted reconnaissance is made easier when a threat focuses on combined arms reconnaissance teams. Aerial reconnaissance, such as air cavalry and UAS, provides early warning of threat elements to ground reconnaissance, identifies obstacles and ambush sites, and helps select the routes for ground reconnaissance. Air elements may also reduce the mobility of counterreconnaissance forces.

Focus

5-53. Another key to successful ISR is the ability to focus the assets on commander’s critical information requirements (CCIR). This focus begins with mission analysis and the commander’s initial planning guidance. It is incrementally refined throughout planning and execution as each ISR effort provides information and permits more specific focus in subsequent efforts. The size and complexity of the urban environment require that the ISR effort center strictly on decisive points or centers of gravity (COGs).

Therefore, the overall ISR effort will have two major focuses. The first is to uncover and confirm information on the decisive points and COG. The second is to determine the approaches (physical, psychological, or both) leading to the decisive points. The first focus will likely drive ISR in support of major operations. The second focus will likely provide the impetus for tactical ISR efforts. For example, special operations reconnaissance might focus on a major command center that controls the entire urban area and that is one of the higher-echelon command’s CCIR. Tactical reconnaissance might focus on the nature of the defense along a particular avenue of approach to the objective.

Integration

5-54. Another important aspect of urban ISR is integration. All reconnaissance capabilities provide both distinctive information as well as information that confirms and adds to that coming from other sources.

Essential to urban ISR is the link between all of these sources, either directly or through an integrating headquarters.

5-55. ISR operations must be vertically and horizontally linked. Vertical links ensure that ISR operations among the various levels of command are complementary and that the information flow between these levels is rapid. Horizontal links ensure that forces operating in close proximity (particularly adjacent units), where areas of interest overlap, can rapidly share results of their individual ISR efforts. Together, this helps ensure that all Army forces share a common operational picture and permits the greatest flexibility and survivability of ISR resources.

5-56. ISR operations also are integrated into the planning system, especially the targeting process. As part of targeting, positioned reconnaissance and surveillance elements may become the trigger and terminal control for applying precision fires when appropriate and after considering the risks of compromise of the 26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-13

Chapter 5

position or platform. ISR operations and plans must also be synchronized with the air tasking order, as many surveillance platforms are coordinated on the same timeline.

Flexibility

5-57. The urban ISR effort must be more flexible than in other operations. This flexibility permits the ISR

effort to meet unforeseen circumstances and to deal with the challenges of the urban environment. As indicated previously, the urban environment is particularly difficult to penetrate. The practical effects of this characteristic are that—

z

The initial ISR effort may not be as successful as in other operations.

z

More intelligence requirements may be discovered later while executing ISR operations than otherwise.

z

The threat may be more successful in active counterreconnaissance because of the concealment advantages of the urban environment (hiding in structures as well as among the urban population).

Therefore, tactical and operational commanders should consider requesting greater than usual ISR support from higher headquarters. Higher headquarters should be proactive in augmenting units conducting urban operations with additional ISR assets. Additionally, ISR assets remaining under the control of the higher headquarters must respond more quickly to the CCIR of supported commanders. Sequencing reconnaissance missions over time provides flexibility by creating uncommitted reconnaissance assets.

5-58. Time sequencing of ISR assets is essential to flexibility. It makes ISR assets more survivable and allows the intelligence cycle to mature the CCIR. It also creates a ready ISR capability to augment committed forces in critical areas if required or diverts them around centers of threat resistance. If not required, the original ISR tasks can be executed as envisioned in planning. Cueing allows a high-value ISR asset to be able to respond to multiple targets based on an ongoing assessment of the overall reconnaissance effort and the changing CCIR. Redundancy permits the effort to overcome line of sight restrictions, the destruction of an ISR asset, and the ability to combine ISR resources to create combat power if required.

Maximizing the ISR effort requires applying all available ISR assets to support the urban operation.

Additionally, assets—such as air defense artillery and field artillery radars and engineer reconnaissance teams—are integrated into the ISR effort. In urban operations, units will also commit infantry and armor elements (plus their organic reconnaissance elements) into the tactical reconnaissance effort. These units increase the dismount capability and the ability of reconnaissance elements to fight for information and fight through security zones.

INFORMATION OPERATIONS

5-59. Information operations are an integral part of all Army operations and a critical component in creating and maintaining information superiority. The information environment is the sum of individuals, organizations, or systems that collect, process, and disseminate information; it also includes the information itself. In UO, the information environment is extremely dense due to the proliferation of INFOSYS and widespread access to those systems. In urban operations, commanders must consider how the urban environment, particularly the human component, uniquely relates to executing IO. They must also anticipate the threat’s information operation campaign and preclude successful operations on its part.

Overall in regard to the urban society, commanders must convince the urban inhabitants of the inevitable success of UO, the legitimacy of Army actions, and the beneficial effects that Army success will eventually generate.

5-60. Because urban operations are likely to be joint, interagency, and multinational, commanders must guard against various forms of information fratricide as a multitude of actors plan and conduct IO in the urban area. For example, the lead governmental agency’s key IO objective may be to establish the legitimacy of newly formed civilian authorities. In an attempt to develop close relationships with the civilian populace, Army commanders may continue to work closely with traditional, informal leaders to the exclusion of the new authority. These actions, while they are often conducted out of practical and immediate necessity, may run counter to the lead agency’s goal. Overall, Army commanders must nest their IO campaign objectives and themes within those of the lead agency, aggressively coordinate with 5-14

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

other governmental agencies and coalition partners, and synchronize activities down to the tactical level to prevent working at odds and avoid information fratricide. However, the process must not be so centralized and rigid that subordinate units lose the flexibility necessary to develop their own products and themes essential to addressing their own AO and the particular situation that confronts them.

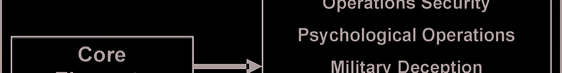

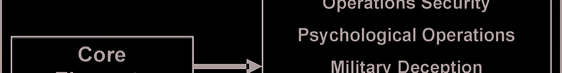

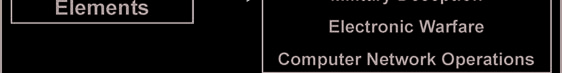

5-61. IO are executed using core and supporting elements and related activities (see Figure 5-3 and FM 313). The elements of IO are employed in either an offensive or defensive role. Many aspects of IO are not affected differently in an urban environment from any other environment. The following sections outline some IO considerations unique to urban operations.

Figure 5-3. IO elements and related activities

Operations Security

5-62. In the urban environment, Army forces can leverage existing urban infrastructure, including the communications and information infrastructure, to enhance Army operations. The danger in integrating these systems is violating OPSEC. Commands ensure that Army forces use only approved systems and proper safeguards exist. Commands also supervise subordinate units for inadvertent breaches of OPSEC

policies when using existing urban systems. Finally, established OPSEC procedures must be reasonable and practical. Overly complicated and stringent procedures increase the likelihood that unintentional OPSEC violations may occur as Army forces seek to rapidly accomplish the mission.

5-63. Of particular concern are computers (see also the discussion of Computer Network Operations below). During longer-term UO, commanders will constantly be upgrading and improving the quality of life for their soldiers through the establishment of well-resourced forward operating and sustainment bases.

This will likely include the provision of unclassified access to the Internet and e-mail allowing Soldiers to communicate with friends and families around the world. E-mail addresses, facsimile numbers, cell phone numbers, photographs, and other sensitive (but unclassified) information can be valuable sources of threat information. Soldiers must be periodically trained and reminded of everyday procedures to combat potential threat exploitation of these unclassified sources (such as not opening e-mails from unknown sources as they may harbor Trojan programs and viruses).

5-64. To compound concerns, commanders will also establish protected systems to disseminate tactical lessons learned to individual soldiers. This creates the potential that Soldiers can inadvertently release classified information about ongoing operations to threat intelligence systems. In addition to OPSEC

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-15

Chapter 5

training and persistent awareness, commanders must establish procedures to shutdown unclassified Internet and e-mail access immediately, both before and after critical events, to mitigate potential OPSEC

violations. (Commanders may also need to randomly shutdown Internet and e-mail access as part of their overall OPSEC measures to preclude such information blackouts serving as a potential warning of impending operations.) Technical surveillance countermeasures—the identification of technical collection activities conducted by threat intelligence entities—will be an important CI service to identify this and other technical OPSEC concerns.

5-65. The close proximity of Army operations to a civil population, particularly in stability and civil support operations, makes Army activities themselves an additional OPSEC concern. Hostile civilians or other threats integrated into the urban population may have more chances to observe Army activities closely. Such observations can provide insight into tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) and expose operational vulnerabilities. However, threats may coerce even friendly civilians to provide a threat with EEFI. Therefore, commanders in an urban environment must ensure that civilians cannot observe critical TTP. Any observable patterns and TTP vary and are supplemented with deception efforts. Physical security is increasingly important in urban areas to control civilians’ access. Although many urban operations require close coordination with NGOs, commanders should screen information provided to these organizations to protect EEFI. Release of EEFI to NGOs is controlled and done with full recognition and understanding of potential consequences—the benefits must far outweigh the risks involved. (Even the best-intentioned NGO might inadvertently compromise security. For example, by revealing that a commander has closed a particular route the next day, the NGO may unwittingly reveal the objective of a pending offensive operation.)

Psychological Operations

5-66. PSYOP aim to influence the behavior and attitude of foreign audiences, both military and noncombatant, in the urban environment. PSYOP are a force multiplier and contribute in many ways to mission success (see FM 3-05.30). Effective PSYOP focuses on transmitting selected messages to specific individuals and groups in order to influence their actions. Their ability to influence the attitudes and disposition of the urban population cannot be overstated. While the complexity of the societal component of the urban environment can make PSYOP challenging, the urban society also offers many options and resources. Potentially, PSYOP (with other political and economic actions) may help limit or preclude the use of military force in urban areas. In some circumstances, UO may be relevant to the major operation only in terms of their psychological effect.

5-67. The positive influence created by PSYOP is often useful in developing an effective HUMINT

capability particularly in an urban area where many civilians actively or passively support the threat.

Persuading and influencing a few to support friendly forces may pay great dividends. These few supporters may allow Army forces to penetrate the urban area and obtain essential information. Such information can apply to threat capabilities, threat intentions, and even the urban environment itself.

5-68. PSYOP, combined with other elements of offensive IO, aid in isolation of a threat—a critical shaping action for any urban operation. For example, commanders may use PSYOP to inform civilians about new food distribution points located away from urban combat operations. This action supports the UO fundamental of separating combatants from noncombatants and helps to further isolate the threat (both physically and psychologically) from the civilian populace. Aside from projecting a positive image of friendly forces over threat forces, PSYOP can also isolate the threat by identifying and exploiting ethnic, cultural, religious, and economic differences between the elements of the civilian populace and threat forces as well as the differences among supportive and unsupportive civilian factions. The complexity of the urban environment enables quick changes in opinion or attitude. Commanders must continually evaluate the results of PSYOP for mission relevance.

Military Deception

5-69. Urban operations present numerous challenges to tactical commanders; however, higher-level commanders may help to mitigate some challenges through effective military deception Commanders can use military deception efforts designed to mislead threat decision makers as to friendly force disposition, 5-16

FM 3-06

26 October 2006

Contemplating Urban Operations

capabilities, vulnerabilities, and intentions. Military deception actions may allow commanders to achieve tactical surprise or improve relative combat power at a selected location. For example, allowing the threat to observe certain activities on a selected avenue of approach may cause the threat to shift his forces (and effort) to the area perceived to be threatened. (This movement may also aid in determining the overall disposition of threat forces and intentions.) Repositioned forces or effort to activities or locations that are not decisive to the achievement of friendly objectives, combined with other IO designed to overwhelm threat information and intelligence systems, may create the force and tempo differential necessary to achieve success. Commanders should tailor urban deception plans to the specific urban area, paying close attention to the societal characteristics of the target population.

Electronic Warfare

5-70. Electronic warfare (EW) includes all actions that use electromagnetic or directed energy weapons to control the electromagnetic spectrum or to attack a threat. Conducting EW in urban areas seeks to achieve much the same results as in other environments. A major consideration in urban areas is collateral effects on portions of the urban infrastructure that rely on the electromagnetic spectrum for service. Thus, precision is a major factor in planning for EW operations. For example, EW attacking a threat’s television broadcasts avoids affecting the television broadcasts of neutral or friendly television. Likewise, EW

attacking military communications in a large urban area avoids adversely affecting the area’s police and other emergency service communications. Urban offensive and defensive operations will have the least restrictions on EW operations while urban stability may have significant constraints on using EW

capabilities.

Computer Network Operations

5-71. Computer network operations (CNO) include computer network attack (CNA), computer network defense (CND), and computer network exploitation (CNE). CNO are not applicable to units at corps and below. Echelons above corps (EAC) units will conduct CNA and CNE. If tactical units require either of these network supports, they will request it of EAC units.

Computer Network Defense

5-72. In urban operations, CND will require extreme measures to protect and defend the computers and networks from disruption, denial, degradation, or destruction. The nature of the urban environment and configuration of computer networks provides the threat with many opportunities to interdict local area networks (LANs) unless monitored by military forces. LANs controlled by military forces are normally more secure than the civilian infrastructure. Commanders should prepare for opportunities by the threat to insert misinformation.

Computer Network Attack

5-73. Considerations regarding the execution of CNA in urban operations are similar to those of EW: CNAs that do not discriminate can disrupt vital civilian systems. However, possible adverse effects on the civilian infrastructure can be much larger—potentially on a global scale. In the short term, CNAs may serve to enhance immediate combat operations but have a debilitating effect on the efficiency of follow-on urban stability operations. Because of these far-reaching effects, tactical units do not execute CNA. CNA is requested of EAC units. EAC units will receive all requests from lower echelons, carefully consider second- and third-order effects of CNA, and work to ensure its precise application.

Computer Network Exploitation

5-74. CNE consists of enabling operations and intelligence collection to gather data from target or adversary automated INFOSYS or networks. Tactical units do not have the capability for CNE. CNE

contributes to intelligence collection at EAC. In UO, CNE will be centrally controlled.

26 October 2006

FM 3-06

5-17

Chapter 5

Physical Destruction

5-75. Physical destruction includes those actions—including direct and indirect fires from air, land, sea, space, and Special Forces—taken with, to augment, or supplement IO actions. Like many other IO

elements, major concerns with employing physical destruction in UO are precision and follow-on effects.

Thus, commanders using physical destruction to support IO must adhere to the same constraints as all other urban fires.

Information Assurance

5-76. Information assurance in UO takes on an added dimension. As with other operations, availability of information means timely, reliable access to data and services by authorized users. In UO, the timeliness of information may be restricted because structures block the transmission waves. The need for retransmission facilities may overwhelm the signal community. The reliability can be questioned because of the blockage between units and communications nodes. Unauthorized users may intercept the communications and input misinformation or disinformation. Commanders must protect the integrity of all information from unauthorized changes, including destruction. INFOSYS with integrity operate correctly, consistently, and accurately. The authentication of information may be accomplished by sophisticated electronic means. However, it is more likely that communications-electronics operating instructions authentication tables will authenticate the information. Commanders should consider the confidential nature of all information in UO and establish procedures to protect the information from unauthorized disclosure. Of additional