National and Imperial Power in 19th-Century U.S. Travel Fiction

Non-fiction travel writing emerged within the U.S. as one of the dominant literary genres of the nineteenth century. Masses of readers consumed these travelogues as proxies for journeys that they did not have the means, or perhaps sometimes even the desire, to make personally. It comes as little surprise, then, that fictional counterparts to travel narratives appeared consistently throughout the century as well. [Please see the module entitled “The Experience of the Foreign in 19th-Century U.S. Travel Literature” for a positioning of these themes within non-fiction travel narratives.] After a brief survey of some of the more significant examples of nineteenth-century U.S. travel fiction, we will turn our attention to the connections between these works and George Dunham’s journal A Journey to Brazil

(1853) - located in Rice University's Woodson Research Center as part of the larger ‘Our Americas’ Archive Partnership. What we will discover is that Dunham’s travelogue shares with these novels a serious investment in the evolving nature of national and imperial power in the nineteenth century.

Travel played a key role in several of the female-authored sentimental novels that were so central to the reading habits of American women, including Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World (1850) and Maria Cummins’ El Fureidis (1860). Moreover, some of the century’s foremost canonical authors deployed this trope as the core foundation for their texts, none more so than Herman Melville. Melville drew on his own history traveling the world aboard various commercial ships in order to inform such seminal works as Moby-Dick (1851) and "Billy Budd" (1924, published posthumously). Though not as widely read, Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838), anticipates in many ways Melville’s early work, predating those publications by nearly a full decade. As Melville would in novels such as Typee (1846), Omoo (1847), and Mardi (1849), Poe displayed a keen interest in the emergent political relationship between the U.S. and the South Pacific as well as the power dynamics that typified life aboard a sailing vessel.

How, then, do we productively read Dunham’s Journey to Brazil alongside these classics of American literature? On a purely schematic level, the outline of the action in Dunham’s travelogue resembles to a great extent that found in the novels of Poe and Melville. The early sections of these works all feature their protagonists on board a ship (named the Montpelier in Journey to Brazil), embarking on a voyage to a foreign territory. The latter portions, then, chronicle the characters’ adventures in these distant lands – Dunham in Brazil, Arthur Gordon Pym on an island in the South Pacific named Tsalal, and Melville’s protagonists from his “South Seas” novels across a variety of South Pacific islands. More interestingly, perhaps, these works share thematic threads that grow out of their similar content. Like Poe and Melville, Dunham transforms the activity of travel into a meditation on the formation, the execution, and the reach of U.S. national power. The experience of characters with life aboard commercial sailing vehicles as well as with foreign countries and peoples prompts an evaluation of both the U.S.’s own internal national formations and its evolving relationship to other locales across the globe. It is quite often through travel literature that commentators articulated the imperialist ambitions of the nineteenth-century U.S., whether forwarding them as a political agenda to be pursued or critiquing them as an affront to republican principles. As Dunham’s journal further demonstrates, nineteenth-century U.S. travel writing, fictional and non-fictional alike, became a discursive staging ground for the negotiation of numerous national and imperial anxieties.

Though utilizing different techniques of inquiry, Dunham, Poe, and Melville all consider the shifting relationship between a citizen and his country of origin after the citizen enters into the international arena. In their works, Poe and Melville tend to address the question of national order and power through the strategy of metaphor, relying on the figure of the ship as a symbolic stand-in for the nation itself. Through the figure of Ahab in Moby-Dick, Melville explores how powerful leadership can so quickly slip into obsessive psychosis, plunging the citizen-subject into ever more precipitous circumstances. In The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Poe foregrounds an on-ship mutiny in order to emphasize the fragility of social order, forcing readers to contemplate the ease and violence through which social and legal bonds can be dissolved. Poe is also interested in the ways in which the citizen-subject abandons national laws and hierarchies once the boundaries of the nation have been crossed and left behind; implicit in his novel is a certain degree of degeneracy on the citizen’s part when they are not within the confines of established social order (some of the mutiny’s survivors flirt with cannibalism before being miraculously rescued by a passing British ship).

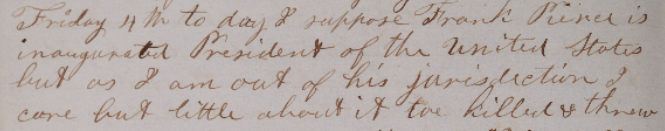

Dunham is more literal in his addressing of the relationship between traveler-citizen, himself, and his home country, the U.S. After a few days on board the Montpelier, he writes almost in passing, “today I suppose Frank Pierce is inaugurated President of the United States but as I am out of his jurisdiction I care but little about it” (see Figure 1). Once he has arrived in Brazil, he notes a visit to the “American Consul,” compelling one to ask after the role of the U.S. in Brazil as well as what privileges Dunham might continue to enjoy as an American citizen even while on foreign soil. Journey to Brazil is a text that, like much of the travel literature of its day, questions the place of the nation and its citizen-subjects within an increasingly tangled set of international relations.

For readers of these texts, it is the relationship, or potential relationship, between the U.S. and other countries that takes center stage once the protagonists arrive at their destination. The novels of Melville and Poe were informed by the growing economic interest on the part of U.S. merchants in the South Pacific. As commercial activity increased in this portion of the globe, many observers agitated for the U.S. government to protect and facilitate the activities of these merchants. The disastrous encounters between the novels’ characters and the island natives seems to warn against U.S. imperial involvement so far beyond its territorial boundaries. That being said, in a series of articles he wrote for The Southern Literary Messenger around this same period, Poe advocated quite clearly for an enhancement of U.S. interests in the South Pacific, so by no means can we assume that the political leanings of these authors were set in stone.

Much like Poe in Arthur Gordon Pym, Dunham devotes a fair amount of his text to cataloguing and attempting to classify the exotic plant-life and wildlife that he encounters over the course of his journey. Dunham recounts that, during a hunting trip in Brazil, “I shot three large birds two of them was kinds that I had shot before but one was a long necked blue bird like some of our shore birds and when we got back he wanted my gun to shoot an owl he took it and went out and in about five minutes he came in with the most queer looking thing of owl kind I ever saw it was about four feet across the wings nearly white and the face looked almost like a human being” (154). These passages may seem innocent enough; however, Dana Nelson explains in The Word in Black and White that any instance in nineteenth-century U.S. writing of the accumulation and categorization of scientific knowledge regarding foreign territories portends some degree of imperialistic investment and desire. So although Dunham may have had no interest in presenting Brazil as a potential U.S. colony, it is possible, even likely, that he was adopting certain techniques and styles from other travel narratives that did possess an imperialistic bent.

Another instance in the journal that finds Dunham reflecting on the connections between the U.S. and Brazil centers around their respective celebrations of independence. He reflects, “I think there is as much money spent in Brazil for powder and fireworks every week as there is in the United States on the fourth of July the 2nd day of July they celebrate their Independence and it is a queer kind of independence to make much fuss about” (111). Here Dunham is forced to recognize, even as he struggles to downplay, the commonalities between the U.S. and other places throughout the Americas, parallel histories that revolve around settler colonialism, anti-colonial independence, and African slavery. By reading Journey to Brazil carefully, one can detect the multiple strands for reading the nineteenth-century relationship between the U.S. and the rest of the hemisphere. Is that relationship one of imperialist domination, as presaged in José Martí’s brief essay “Our America” and analyzed in scholarly works such as Gretchen Murphy’s Hemispheric Imaginings: The Monroe Doctrine and Narratives of U.S. Empire? Or is that relationship better explained by the set of mutual cultural, political, and economic exchanges chronicled by Anna Brickhouse in her book, Transamerican Literary Relations and the Nineteenth-Century Public Sphere? The real value of the Dunham journal, finally, lies in its ability to remind us that for writers and readers in the nineteenth-century U.S., concerns about the intersections between the national and the foreign stretched beyond the ever-expanding western frontier, beyond even a burgeoning spot of economic activity such as the South Pacific, and included, in fact, the entirety of the Americas.

Bibliography

Brickhouse, Anna. Transamerican Literary Relations and the Nineteenth-Century Public Sphere. New York: Cambridge UP, 2004.

Cummins, Maria. El Fureidis. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1860.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick, or, The Whale. Berkley: U of California P, 1979.

-----. Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life; Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas; Mardi: A Voyage Thither. New York: Viking Press, 1982.

Murphy, Gretchen. Hemispheric Imaginings: The Monroe Doctrine and Narratives of U.S. Empire. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2005.

Nelson, Dana. The Word in Black and White: Reading “Race” in American Literature. New York: Oxford UP, 1992.

Poe, Edgar Allan. The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket. New York: Modern Library, 2002.

Warner, Susan. The Wide, Wide World. New York: Putnam, 1851.