Puppets of Italy and Southern Europe

“Into whatever country we follow the footprints of the numerous, motley family of puppets, we find that however exotic their habits may be on their first arrival in the land they speedily become reflexes of the peculiar genius, tastes and characteristics of its people. Thus in Italy, the land of song and dance, of strict theatrical censorships and of despotic governments, we find the burattini dealing in sharp but polished jests at the expense of the rulers, excelling in the ballet and performing Rossini’s operas without curtailment or suppression, with an orchestra of five or six instruments and singers behind the scenes. The Spanish titere couches his lance and rides forth to meet the Moor and rescue captive maidens, marches with Cortez to the conquest of Montezuma’s capital or enacts with more or less decorum moving incidents from Holy Writ. In the jokken and puppen of Germany one recognizes the metaphysical and fantastical tendencies of that country, its quaint superstitions, domestic sprites and enchanted bullets. And in France, where puppet shows were early cherished and encouraged by the aristocracy as well as by the people, we need not wonder to find them elegant, witty and frivolous, modelling themselves upon their patrons.”

Eclectic Magazine (1854).

EVERY country of Europe has had marionettes of one type or another persisting from very early stages through centuries of national vicissitudes. Italy, however, may be considered the pioneer, the forerunner of them all. It was wandering Italian showmen who carried their castelli dei burattini into England, Germany, Spain and France, and these countries seem to have adopted puppet conventions, devices and dialogues long established by the Italians, gradually adapting them to their own tastes. The Italians have always displayed great ingenuity and perseverance in developing and elaborating their marionettes; indeed, this may be both cause and result of the perpetual joy they appear to derive from them.

There are numerous records in early Italian history of religious images in the cathedrals and monasteries, marvellous Crucifixes, figures of the Madonna and of the saints that could turn their eyes, nod their heads or move their limbs. These were the solemn forebears of the Italian fantoccini! Moreover very early it became customary for special occasions to set up elaborate stages in the naves and chapels of the churches upon which were enacted episodes from the Bible or from the lives of the martyrs. The performers were large or small figures carved and painted with rare skill and devotion, sometimes elaborately dressed and bejeweled and frequently moved by complicated mechanism. It was not unusual, in the presentation of sacred plays, to utilize both puppets and human actors together.

Vasari in his Life of Il Cecca tells us that, “Among others, four most solemn public spectacles took place almost every year, one for each quarter of the city with the exception of S. Giovanni for the festival of which a most solemn procession was held, as will be told. S. Maria Novella kept the feast of Ignazio, S. Croce that of S. Bartholomew called S. Baccio, S. Spirito that of the Holy Spirit and the Carmine those of the Ascension of Our Lord and the Assumption of Our Lady.” Of the latter he continues, “The festival of the Ascension, then, in the church of the Carmine, was certainly most beautiful, seeing that Christ was raised from the mount, which was very well contrived in woodwork, on a cloud about and amidst which were innumerable angels, and was borne upwards into a Heaven so admirably constructed as to be really marvellous, leaving the Apostles on the mount.” We may read in great detail of the impressive Paradiso, an arrangement of vast wheels moving in ten circles to represent the ten Heavens. These circles glittered with innumerable lights arranged in small suspended lamps which represented stars. From this Heaven or Paradiso there proceeded by means of two strong ropes, pulleys and counterweights of lead, a platform which held two angels bound firmly by the girdle to iron stakes. These in due time descend to the rood-screen and announce to the Savior that He is to ascend into Heaven. “The whole apparatus,” continues the historian, “was covered with a large quantity of well-prepared wool and this gave the appearance of clouds amidst which were seen numberless cherubim, seraphim and other angels clothed in various colors.” The machines and inventions were said to have been Cecca’s, although Filippo Brunelleschi had made similar things long before.

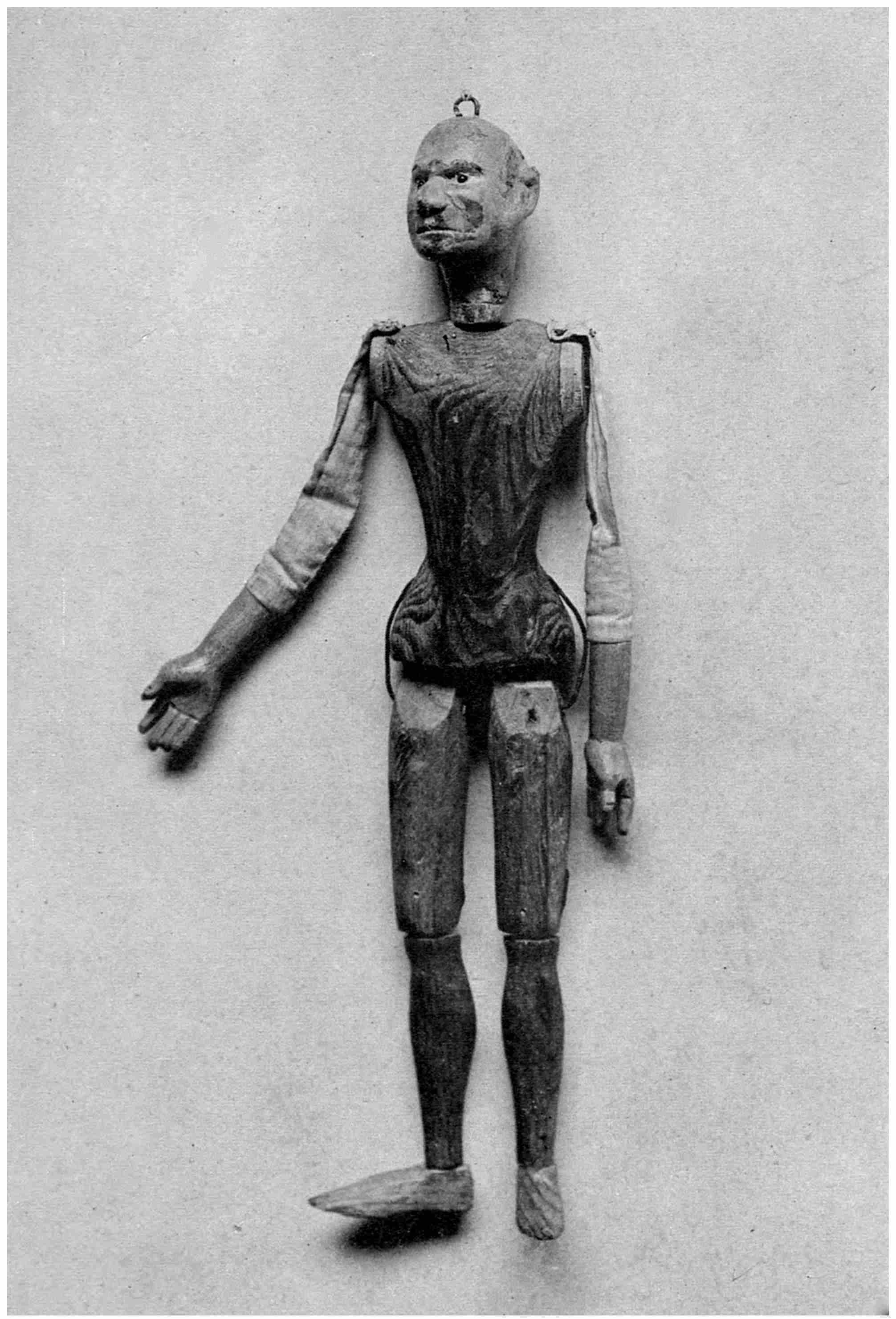

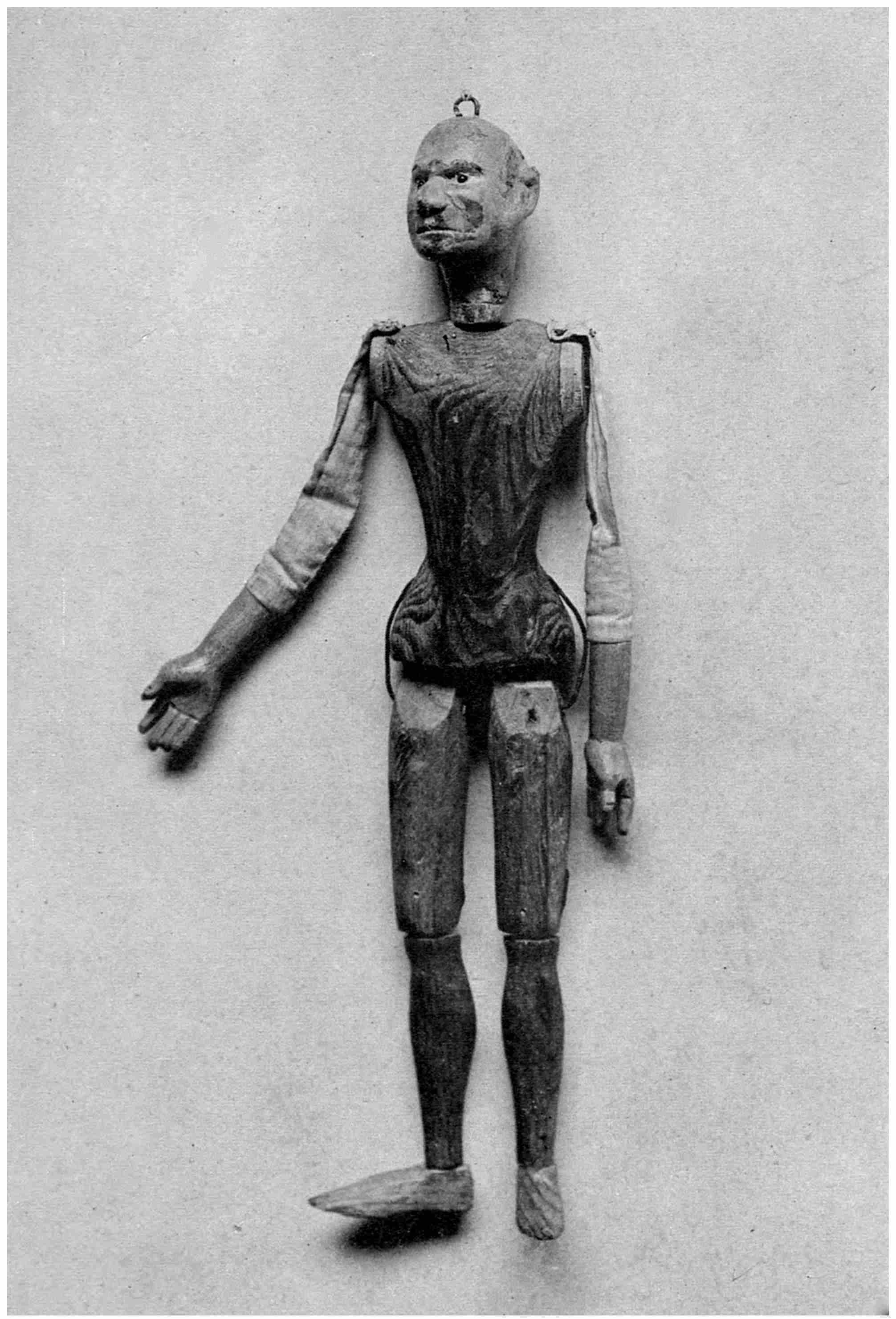

A WOODEN ITALIAN PUPPET, QUITE OLD

[Property of Mr. Tony Sarg]

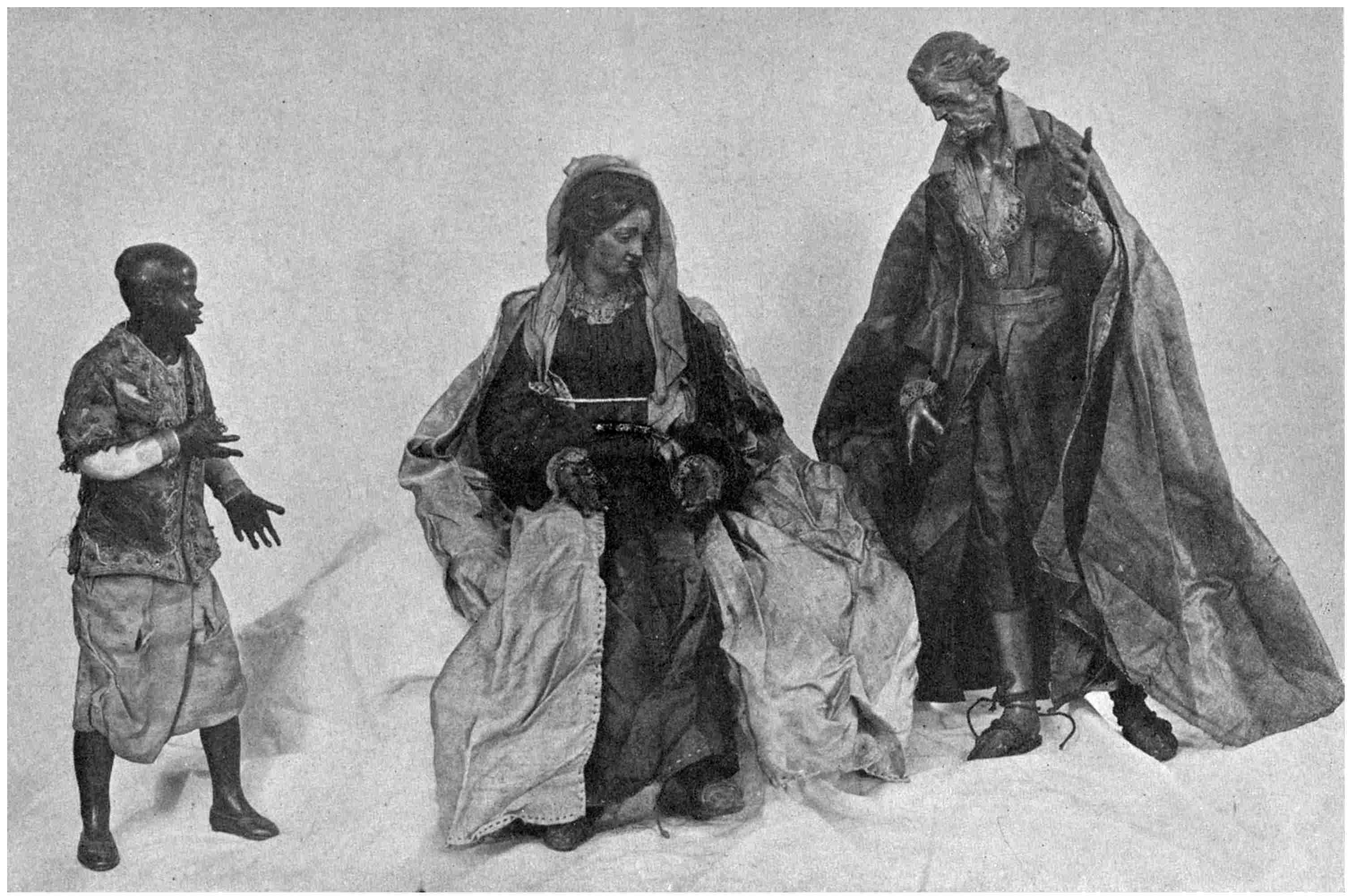

“It has been pointed out,” writes E. K. Chambers in the second volume of his Mediaeval Drama, “that the use of puppets to provide a figured representation of the mystery of the nativity seems to have preceded the use for the same purpose of living and speaking persons; and furthermore that the puppet show in the form of the Christmas Crib has outlived the drama founded upon it and is still in use in all Catholic countries.” Ferrigni describes a cathedral near Naples where this ancient custom is still continued, the church being quite transformed for the occasion, its walls hidden by scenery and an imitation hill constructed at the top of which stood the Presepio. Moving figures travelled up the hill toward the manger of Bethlehem, which was illumined by a great light. I have heard such spectacles described by travelers with much enthusiasm and not a little awe. Imagine the deep impression, the reverent delight, produced among the devout worshippers in mediaeval times!

It must be admitted that many prelates condemned the use of these religious fantoccini as smacking sinfully of idolatry. Abbot Hughes of Cluny denounced them in 1086, Pope Innocent in 1210 and others also, from time to time. But canons were never able to quite eradicate the cherished custom, and the little figures always reappeared inside the churches and in adjacent cloisters and cemeteries for spectacles, mysteries and masks. The decree of the Council of Trent, however, was instrumental in forcing most of them out of the churches, so that in the sixteenth century they were generally to be found roaming about the countryside and giving performances in the marketplaces and at fairs.

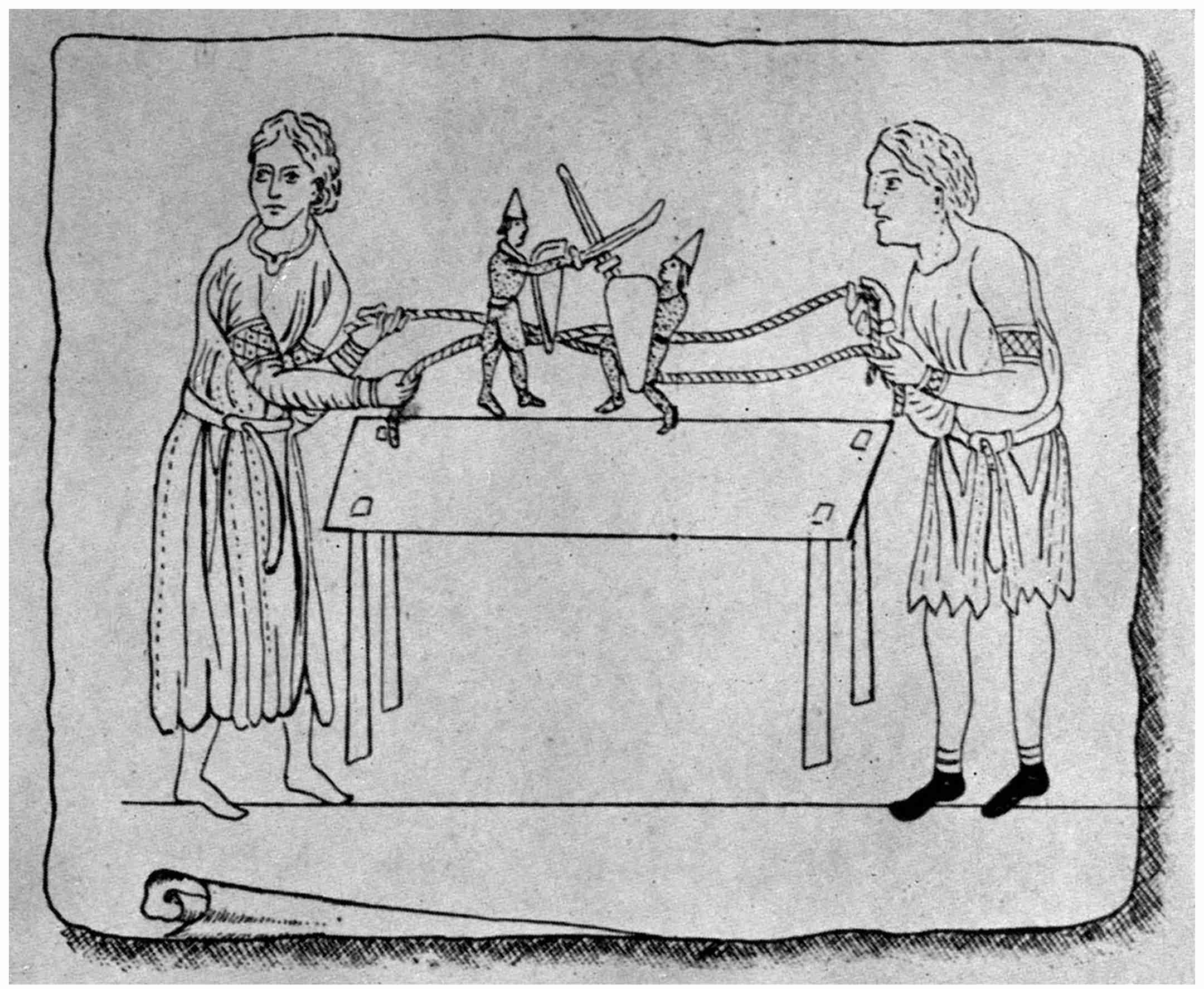

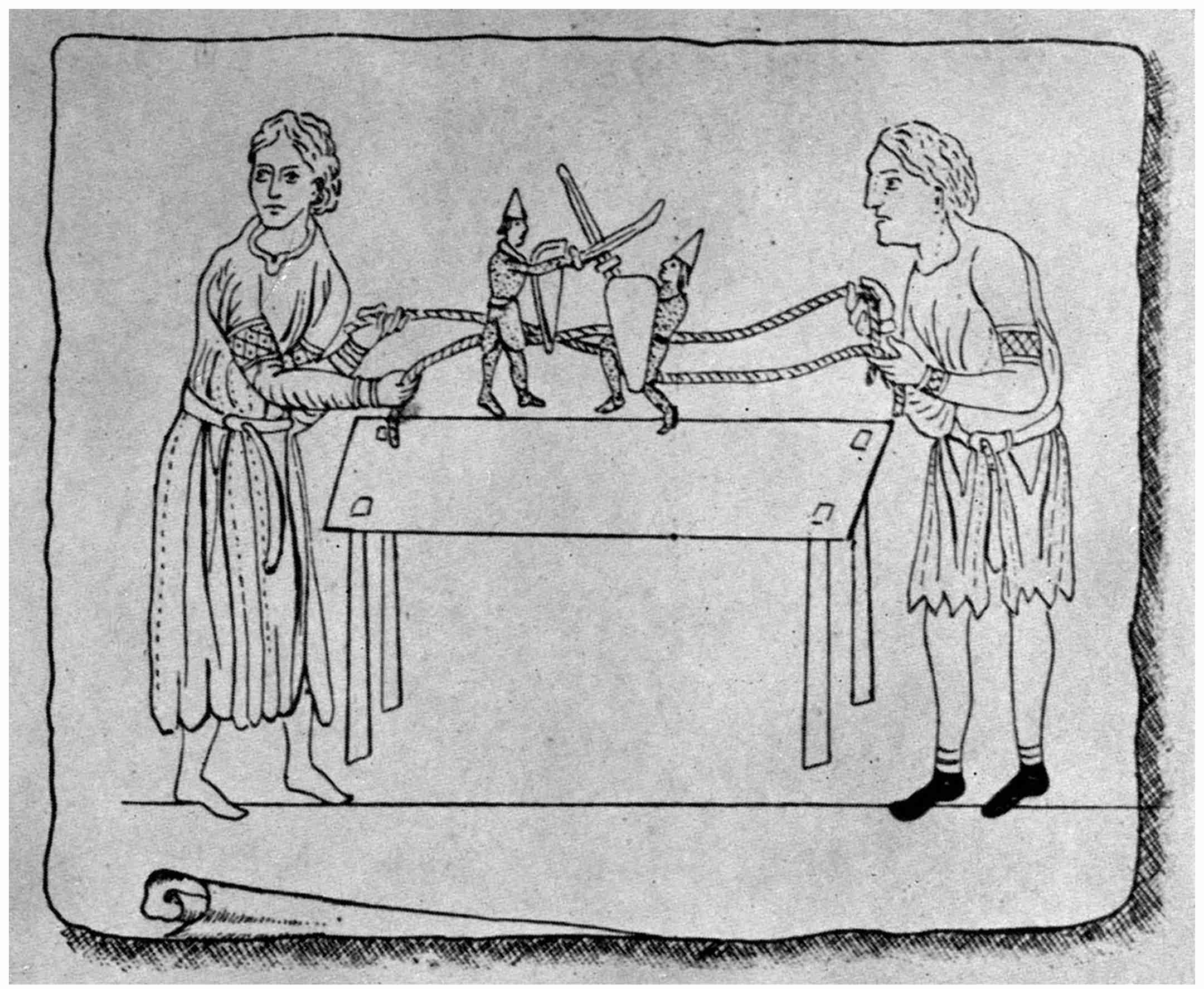

MEDIAEVAL MARIONETTES

[From an illustration in a twelfth-century manuscript in the Strassbourg library]

There are many types of Italian pupazzi. They have been called by many names and exhibited in many manners. They are designed and dressed and manipulated in innumerable ways. In a twelfth-century manuscript discovered in the Strasbourg library there is an illustration of very primitive little figurini. They represent a pair of warriors caused to fight by means of two cords; the action is horizontal. Somewhat the same principle is employed to operate simple little dolls dancing on a board, generally a couple of them together, the string tied to the knee of the puppeteer. He makes the figures perform by moving his leg and generally plays on a drum or tambourine to accompany the motion. As a rule the name burattini is applied to the dolls with heads and hands fashioned of wood or paper-maché and manipulated by a hand thrust under the empty dress, a finger and a thumb fitted into the two sleeves to work the arms, another finger used to turn or bow the head of the doll. These pupazzi were most frequently played in pairs by travelling showmen with little portable castelli. Fantoccini are the puppets fashioned more or less after the human figure. They are made of cardboard or wood and occasionally in part of metal or plaster. They are sometimes crudely carved, sometimes modelled with attention to every detail. They are operated by means of wires or threads connecting them with the control, which is in the hands of the marionettist standing concealed above. The number and arrangement of threads and controls may be simple or intricate. Sometimes the limbs are wired and all the wires except those of the arms are carried out of the head through an iron tube. Another device is that of wiring the dolls and manipulating them from below by pedals. There is no end to the variety of contrivances invented by the makers of marionettes. The more elaborate dolls are generally exhibited in large and substantial castelli or on permanent stages constructed in private homes or in theatres used entirely for fantocinni, the spectacular effects being carried out on an amazing scale.3

From earliest times the marionettes have been exceedingly popular with both learned and ignorant. Every village was visited by ambulant shows, every city had its large castello, frequently many of them, while noble families had their private puppet theatres and engaged distinguished writers to compose plays. Lorenzo de Medici is said to have enjoyed puppet shows and to have given many of them. Cosimo I is reported to have had the fantoccini in the Palazzo Vecchio, Francesco I in the Uffizi: Girolamo Cardan, celebrated mathematician and physician wrote in 1550, “An entire day would not be sufficient in which to describe these puppets that play, fight, shoot, dance and make music.” Leone Allaci, librarian of the Vatican under Pope Alexander VII, stopped nightly to watch the burattini play. Prominent mechanicians and scientists used their skill to create clever pupazzi; artists have left us charming pictures of groups thronging around the castelli in the public roads; poets and scholars wrote plays for the marionettes.

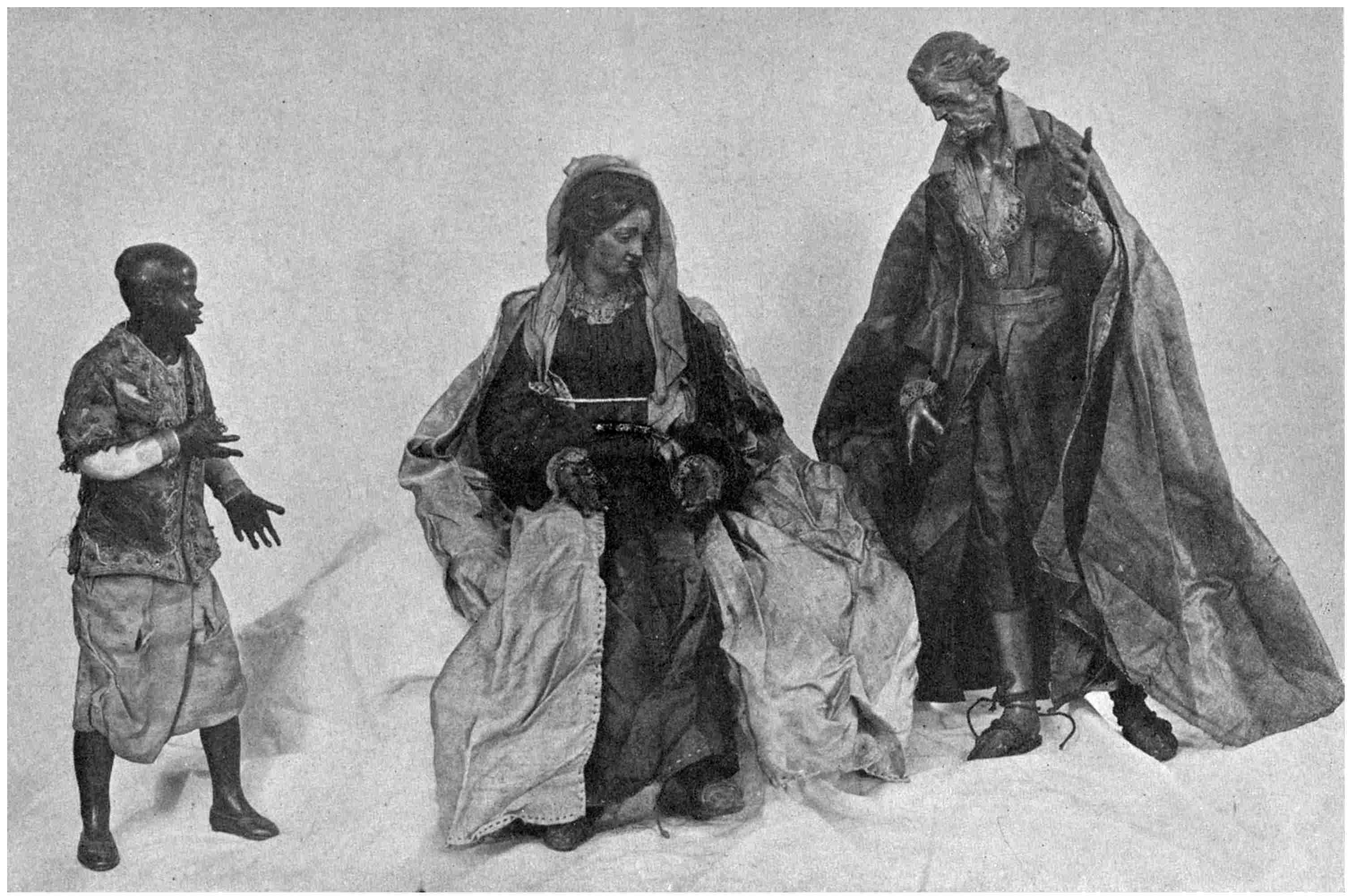

FIGURES USED FOR CHRISTMAS CRIB INSIDE THE CHURCH

Seventeenth or eighteenth century

[From the collection of Mr. Sumner Healey, New York]

In the beginning the repertory of the pupazzi was derived entirely from the sacre rappresentazione, consisting of scenes from the Old and the New Testaments, stories of miracles and martyrdoms. Soon a comic element was allowed to creep in, the better to hold the attention of the audience. Fables were introduced for variety, and episodes from heroic tales of chivalry, also satires reminiscent of Roman decadence. The latter were performed by puppets fantastically dressed and burlesqueing local types, and, naturally, speaking in the native dialect of those particular characters. The showman improvised the dialogue to fit the occasion, using only a skeleton plot to direct the action just as did the actors of the Commedia dell’Arte. “Thus,” claims an authority on Italian puppetry, “on this humble stage were born types of the ancient Italian theatre, the immortal masks.” It might be as difficult to prove as to disprove this statement, but at any rate the pupazzi had a hand in popularizing and perpetuating the famous maschere.

At this point it might be well to digress for a moment and to consider the commedia dell’arte which is so interwoven with the story of Italian marionettes. Along with the commedia erudita which was flourishing at the courts of the great Italian princes there developed an extemporaneous, popular theatre depending greatly for its spirit upon the invention and talent of the actors. Perhaps the beginnings of its gay humor may be traced back to the comic and local elements introduced into the early sacre rappresentazione. Perhaps the characters were copied from the familiar buffoons of Latin comedy. At any rate, the well-known masks or personaggi of the cast represented amusing types from all strata of Italian society, and each was immediately recognizable by a conventionalized and rather grotesque costume. Arlecchino, who originally came from Bergamo, is the chief personage of this motley group. He is a unique figure in his strange suit of multi-colored patches, his black mask, his peculiar weapon, all reminiscent of the Roman Histrio. At first conceived as a happy, simple fellow, he became in time a character of unbridled gayety and pointed wit. Then there was Pulcinella, descended probably from the Roman Maccus, a Neapolitan rogue and merry-maker whose white costume serves to accentuate the hump in his back and his other physical peculiarities. There were Scaramuccia, also of Naples, false bravo and coward, Stentorella, from Florence, a mean miserly wretch, Cassandrino, the charming fop and braggart, a Roman invention. Messer Pantalone is a good-natured Venetian merchant deceived by all, Scapino is the mischief maker apt to lead youth astray, Constantine of Verona is “said youth.” Then come Brighella, Capitaine, Pierrot, world renowned, Columbine, Isabella, and a host of other Italian conceptions, to say nothing of Pasquino, Peppinno, Ornofrio and Rosina who are the masks of Sicily.

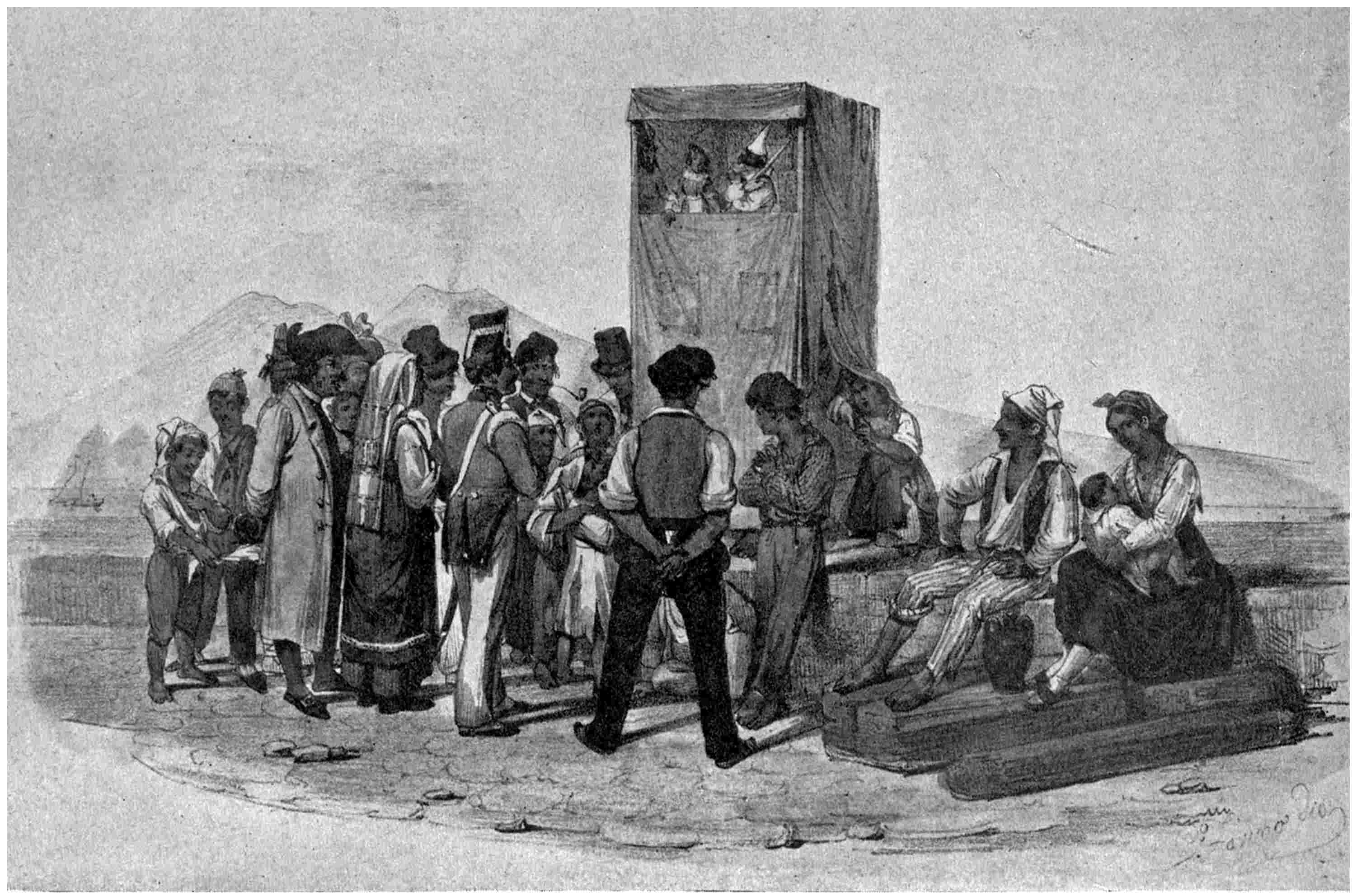

PULCINELLA IN ITALY

[From original color lithograph]

It was customary to have the plot and the principal situations sketchily outlined for the actors. They then went into the play supplying dialogue and improvising action and appropriate jests as the mood of the moment dictated. The humor of the theatre was merry and spontaneous, though frequently extremely broad and of questionable taste. But despite this license of manners, the morals and purposes of the plays were good, levelling shafts of satire against the frauds and abuses of the age, poking fun and scorn at rogueries, hypocrisies, weaknesses. The commedia dell’arte flourished brilliantly for a century or more. Flaminio Scala was the first director who attempted to systematize it. In 1611 he published a number of scenarii and detailed directions for the action. However, in time the unbridled wit degenerated into mere vulgarity, the grace and spontaneity of gesture into absurd acrobatic tricks and grimacing, the bubbling jests and startling situations became stale. It was then that Goldoni came to reform the Italian drama. In his plays, it is true, one may still find traces of the popular masks, but they are relegated to minor rôles, subdued and properly clad. They will never wholly die out.

Through various stages of the Italian drama the marionettes have trailed gayly along, ever adopting the new without discarding the old. Their repertoire is all inclusive. They have enacted sacred dramas and legends of saints, Sansone e Dalila, Sante Tecla, Guida Iscaretta and innumerable others. They have made use of the scenarios of old Latin plays such as Amor non virtoso and Il Basilico di Berganasso. When the bombastic, elaborate plays were discarded by the actors they came into possession of the puppet showmen. Thereafter the burattini became grandiloquent, and stalked about as princes and heroes of tragedy, while their trappings and settings often grew correspondingly elaborate. To fables of heroes and pastoral scenes, to the romances of Paladins and Saracens and spectacular tales of brigands, assassins and tyrants were added the pathetic and romantic melodramas of foreign lands. Il Flauto magico, La donna Serpente, Genovieffa di Brabante, Elizabetta Potowsky, everything was to be seen in the castelli of the fantoccini, even the military plays of Iffland and Kotzebue. Moreover Arlecchino and his band were always allowed to enter at any time, into any situation. Indeed, when the commedia dell’arte became at last discredited on the larger stage it sought shelter with the puppets. Thus in the puppet booths the popular old personaggi were kept alive among the people, where they had, indeed, been ever very much at home.

These old masks continue to be found to-day in the puppet shows of Italy, as are also the melodramatic tragedies popular with the masses and the clever, satirical comedies given in more intellectual circles. Stendhal (Marie Henri Beyle), in his Voyage en Italie, reports that in Rome he witnessed a wonderful performance of Machiavelli’s Mandragore performed for a select and highly cultured circle by marvellous little marionettes on a stage scarcely five feet wide but perfect in every detail. Rome has always abounded in puppet theatres. Ernest Peixotto writes in 1903 that noblemen were in the habit of giving plays acted by fantoccini in their palaces, plays reeking with escapades and political satire that dared not show its face on the public boards. Stendhal wrote also that he found Cassandrino at the Teatro Fiano very much the vogue, presented as a fashionable man of the world falling in love with every petticoat. Teoli, who had made the part famous, was an engraver by profession as well as an expert marionettist. His delightful little Cassandrino was sometimes allowed to appear in a three-cornered hat and scarlet coat suggesting the cardinal, sometimes as a foppish Roman citizen, clever and experienced but still with a weakness for the ladies. He was a charming instrument for voicing popular criticism against the ecclesiastics and the government. What wonder that Teoli’s theatre was sometimes closed and he himself imprisoned? But Gregory XVI reopened the theatre and long after Teoli’s death it remained in the hands of his family.

At the present time in what was formerly this very Fiano theatre, in the Piazza S. Apollinare, there still exists a prominent show of fantoccini. Here the small auditorium is perfectly fitted out for the accommodation of the very respectable middle-class audience with a sprinkling of the aristocracy. The stage is well lighted, there is an orchestra, the dolls are beautifully, nay, elegantly dressed. Here we find Pulcinella entering into the plays, a well-mannered, dexterous Pulcinella. The ballet is amazingly graceful, often ending with a tableau or even fireworks.

The most popular puppet theatre in Rome to-day, however, seems to be that in the Piazza Montanara. Here the rather primitive fantoccini present, most frequently, the ancient tales of chivalry from Ariosto but their repertory also includes such diverse dramatic material as Aeneas, King of Tunis and The Discovery of the Indies by Christopher Columbus. The audience sitting in the pit is composed chiefly of rough, bronzed working men with thick, unkempt hair, a noisy crowd all eating cakes or cracking pumpkin seeds between their teeth. A spectator thus describes a performance: “To-day they are to perform the lovely tale of Angellica and Medoro, or Orlando Furioso and the Paladins. The curtain rises and the marionettes appear. The valiant Roland and Pulcinella, his squire, come forth with a bound and neither of them touches the ground. Roland is covered with iron from head to foot and holds in his hand the Durlindana, [his sword]. Pulcinella has white stockings, a white costume, with wide sleeves, and a white cap with a tassel. The marionettes are two feet high, their limbs perfectly supple, and lend themselves to any movement, etc. etc.”

The same account tells us that the play of Christopher Columbus had been given here fourteen evenings in succession, three times an evening. In it the Indians excited special curiosity, decked out with splendid plumes.

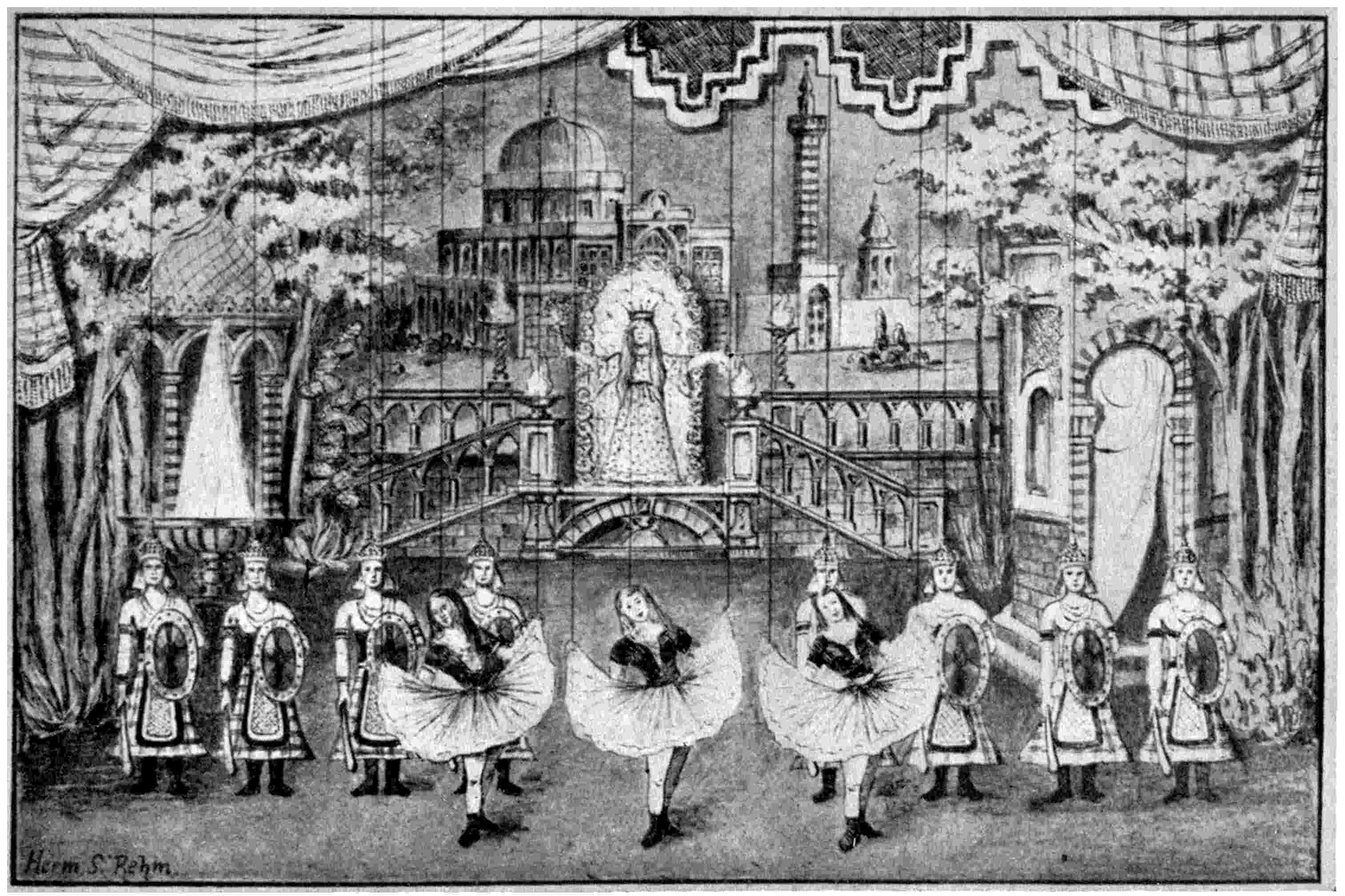

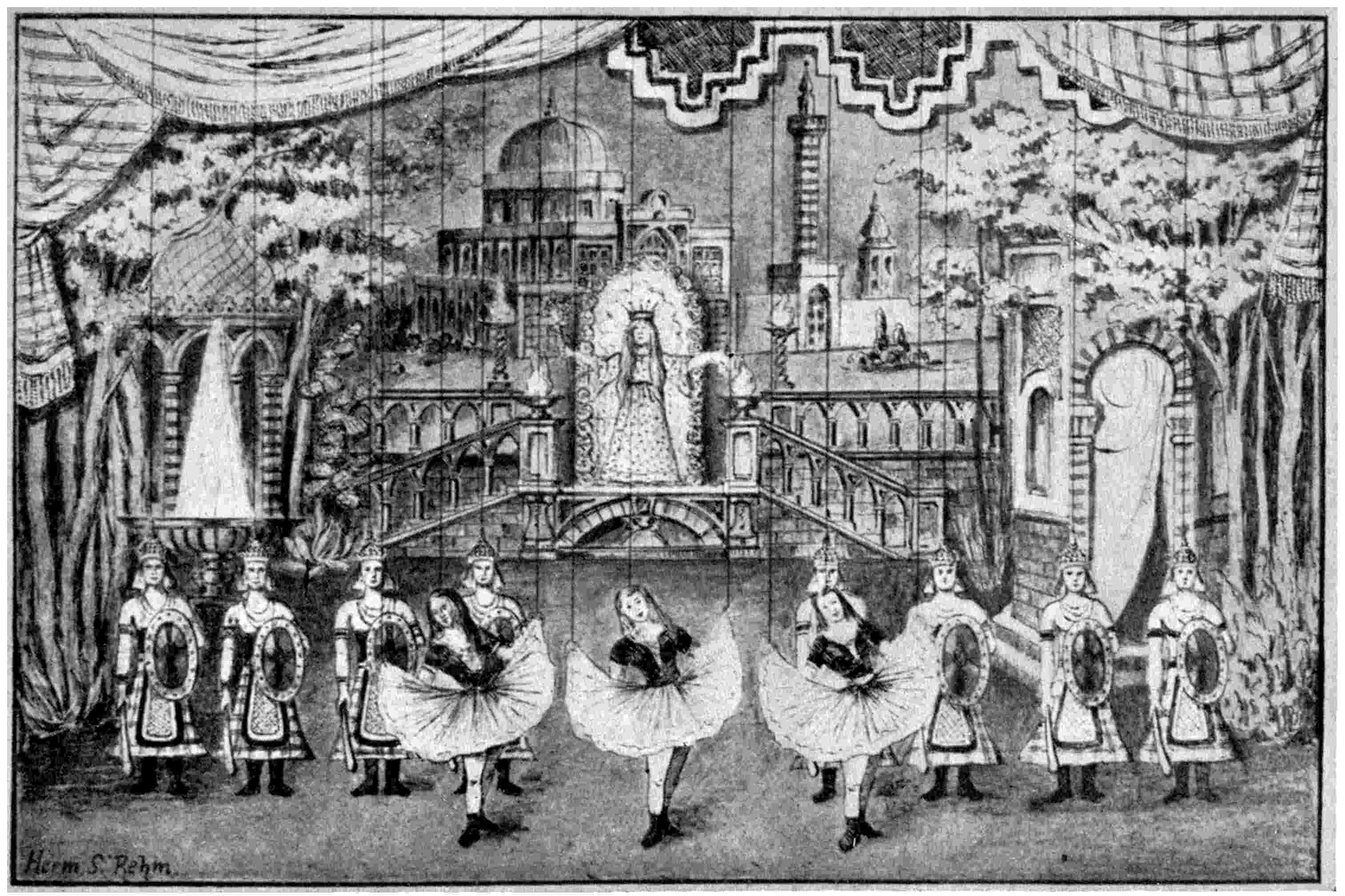

ITALIAN PUPPET BALLET

[From a drawing in Hermann S. Rehm’s Das Buch der Marionetten]

In 1912 Mr. W. Story visited a similar theatre of fantoccini in Genoa where elaborate productions (usually of the wars of the Paladins) were presented to an ever-receptive audience. “What is that great noise of drums inside?” inquired Mr. Story of the ticket seller. “Battaglio,” was the reproving reply, “E sempre battaglie!” (Always battle!) Although this perpetual fray was rather crude, it was followed by an excellent ballet which danced the most intricate steps with masterly ease and grace.

There is an account by Charles Dickens of the show which he witnessed in Genoa. It is too entertaining to be omitted.

“The Theatre of Puppets, or Marionetti, a famous company from Milano, is, without any exception, the drollest exhibition I ever beheld in my life, etc.

“The comic man in the comedy I saw one summer night, is a waiter at a hotel. There never was such a locomotive actor since the world began. Great pains are taken with him. He has extra joints in his legs, and a practical eye, with which he winks at the pit, in a manner that is absolutely insupportable to a stranger, but which the initiated audience, mainly composed of the common people, receive (as they do everything else) quite as a matter of course, and as if he were a man. His spirits are prodigious. He continually shakes his legs, and winks his eye.

“There is a heavy father with grey hair, who sits down on the regular conventional stage-bank, and blesses his daughter in the regular conventional way, who is tremendous. No one would suppose it possible that anything short of a real man could be so tedious. It is the triumph of art.

“In the ballet, an Enchanter runs away with the Bride, in the very hour of her nuptials. He brings her to his cave, and tries to soothe her. They sit down on a sofa (the regular sofa! in the regular place, O. P. Second Entrance!) and a procession of musicians enter; one creature playing a drum, and knocking himself off his legs at every blow. These failing to delight her, dancers appear. Four first; then two; the two; the flesh-coloured two. The way in which they dance; the height to which they spring; the impossible and inhuman extent to which they pirouette; the revelation of their preposterous legs; the coming down with a pause, on the very tips of their toes, when the music requires it; the gentleman’s retiring up, when it is the lady’s turn; and the lady’s retiring up when it is the gentleman’s turn; the final passion of a pas-de-deux; and going off with a bound! I shall never see a real ballet, with a composed countenance, again.

“I went, another night, to see these Puppets act a play called ‘St. Helena, or the Death of Napoleon.’ It began by the disclosure of Napoleon, with an immense head, seated on a sofa in his chamber at St. Helena; to whom his valet entered, with this obscure announcement:

“‘Sir Yew ud se on Low!’ (The ow, as in cow).

“Sir Hudson (that you could have seen his regimentals!) was a perfect mammoth of a man, to Napoleon; hideously ugly; with a monstrously disproportionate face, and a great clump for the lower-jaw, to express his tyrannical and obdurate nature.

“He began his system of persecution by calling his prisoner ‘General Buonaparte’; to which the latter replied, with the deepest tragedy, ‘Sir Yew ud se on Low, call me not thus. Repeat that phrase and leave me! I am Napoleon, Emperor of France!’ Sir Yew ud se on, nothing daunted, proceeded to entertain him with an ordinance of the British Government, regulating the state he should preserve, and the furniture of his rooms; and limiting his attendants to four or five persons. ‘Four or five for me!’ said Napoleon. ‘Me! One hundred thousand men were lately at my sole command; and this English officer talks of four or five for me!’

“Throughout the piece, Napoleon (who talked very like the real Napoleon, and was forever having small soliloquies by himself) was very bitter on ‘these English soldiers’ to the great satisfaction of the audience, who were perfectly delighted to have Low bullied; and who, whenever Low said ‘General Buonaparte’ (which he always did; always receiving the same correction) quite execrated him. It would be hard to say why; for Italians have little cause to sympathize with Napoleon, Heaven knows.

“There was no plot at all, except that a French officer, disguised as an Englishman, came to propound a plan of escape, and being discovered (but not before Napoleon had magnanimously refused to steal his freedom), was immediately ordered off by Low to be hanged, in two very long speeches, which Low made memorable, by winding up with ‘Yas!’ to show that he was English, which brought down thunders of applause. Napoleon was so affected by this catastrophe, that he fainted away on the spot, and was carried out by two other puppets.

“Judging from what followed, it would appear that he never recovered from the shock; for the next act showed him, in a clean shirt, in his bed (curtains crimson and white), where a lady, prematurely dressed in mourning, brought two little children, who kneeled down by the bedside, while he made a decent end; the last word on his lips being ‘Vatterlo.’

“Dr. Antommarchi was represented by a puppet with long lank hair, like Mawworm’s, who, in consequence of some derangement of his wires, hovered about the couch like a vulture, and gave medical opinions in the air. He was almost as good as Low, though the latter was great at all times, a decided brute and villain, beyond all possibility of mistake. Low was especially fine at the last, when, hearing the doctor and the valet say, ‘The Emperor is dead!’ he pulled out his watch, and wound up the piece (not the watch) by exclaiming, with characteristic brutality, ‘Ha! ha! Eleven minutes to six! The General dead! and the spy hanged!’

“This brought the curtain down, triumphantly.”

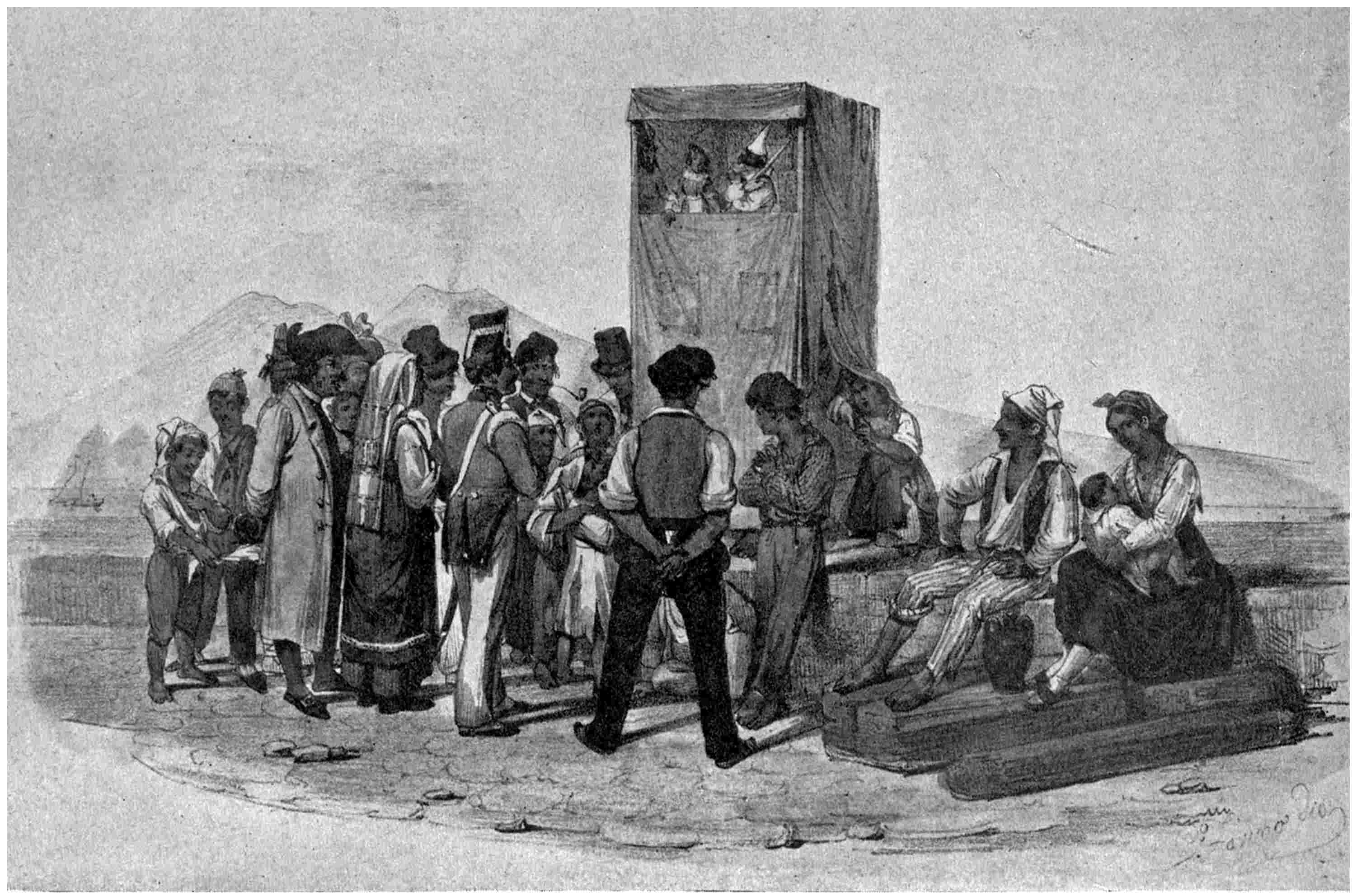

Goethe was greatly interested by the shows in Naples where every event of local interest was introduced upon the puppet stage. The humor of the Neapolitan Pulcinella was often vulgar; ladies were not supposed to visit the shows, although they were frequently given in fine society. On the street where they were most popular, however, they drew about them picturesque audiences reminiscent of Hogarth’s sketches. Pulcinella was made to speak with a squeaky voice by means of the pivetta, a little metal contrivance placed in the mouth of the actor. It is formed of two curved pieces of tin or brass, bound together and hollow inside. The voice, passing through this, acquired a shrill and ridiculous sound.

Until the eighteenth century the puppets enjoyed celebrity and prestige in Venice. Vittorio Malmani tells us that from the sixteenth century when they became the vogue among Italian nobility, Venetian patricians were accustomed to build elaborate little puppet theatres in their palaces. One example of this was that of Antonio Labia, who exactly reproduced in miniature the huge theatre, S. Giovanni Grisostomo, famous throughout Europe, stage, boxes, decorations, machinery, lighting facilities, costumes—everything precisely imitated the larger theatre. The actors were figurines of wax and wood. The first drama produced here was Lo Starnuto d’Ercole (The Sneeze of Hercules) which we may find described in Goldini’s memoirs.

In the Piazza of San Marco and in the Piazzetta until the fall of the Republic, so Malamani tells us, the castelli of the burattini were numerous during carnival time. In the eighteenth century the casotti of Paglialunga and Bordogna were great rival attractions until the former showman died and his little actors went to swell the company of Bordogna, whose descendants continued the theatre throughout the eighteenth century. The casotto of Bordogna has been painted by the brush of Longhi, standing near the great dove of the Ducal Palace.

A. Calthrop tells of his recent visit to a rough little place, Teatro Minerva, where three-foot burattini, looking life size, were manipulated crudely to the intense satisfaction of the audience. He mentions a well-managed maschere, Guillette and her lover, a clownish dwarf, both speaking in the Venetian dialect, and after the play, the marionette ballet. Another account tells of a pretty little puppet theatre with boxes, galleries and parquet where dolls thirty-five inches high play classic tragedy of four or five acts and comedy and pantomime, including always a marvellous ballet. Here the most admired puppet receives encores, even bouquets and very properly bows in response. The stages of such little theatres are as complete as the most luxurious real stages. The figures can sit on chairs, open bureau drawers, carry objects, and they are carefully and beautifully costumed. The dialogue and subjects are far removed from the triviality of the crude castelli, where the pupazzi are manipulated on the fingers of the showman. It is not unusual to witness Nebuccodnoser performed by fantoccini or Rossini’s operas.

In recent issues of The Marionette one will find an enthusiastic eulogy of a remarkable puppet theatre in Torino, the proprietors of which were the Lupi brothers. They had inherited their profession from their grandfather, a wandering showman of Ferrara, and from their father, a man of lively talent who had established the present theatre. The two brothers were named Luigi I and Luigi II, respectively; only one is still living. Their show has been taken far and wide. It travelled from Buenos Aires to London, from Chicago to Venice, and has gained as great applause as did the puppets of the famous Prandi brothers of Brescia in their day. The repertory embraces the universe in time and space, extends from the flood to the siege of Makalle; comprises mythology, natural history and city news; stretches from China to California, from Cafrena to Greenland, from spaces in the air to abysses of ocean, from the circles of Paradise to the caverns of Hell. It includes the old commedia dell’arte, dramas from all literatures, the ballets of Pratesi and Manzotti, the operas of Meyerbeer and Verdi, all the military glories of the nation from the battle of Goito to the occupation