The Puppets in France

“Ainsi font font font

Les petites marionettes

Elles font font

Trois petits tours et puis s’en vont.”

THE French, scarcely less than the Italians, are devotees of the diminutive Polichinelle. Moreover in France this devotion is particularly noticeable in the upper classes. Perhaps it is this interest of aristocratic and cultured circles or possibly the happy genius and good taste of the people themselves which have endowed the marionettes of France with such undeniable charm, a sort of chic cleverness and at times a rare and finished beauty.

The ancient Gauls, before their conquest by the Romans, had great Druid gods, Belen, Esus, Witolf, Murcia, represented by huge and fearful idols which were operated by means of internal mechanism to terrorize into submission the fierce, barbaric worshipers who beheld their solemn gestures. After the conquest Greek and Roman practices were intermingled with barbarian rites and, eventually, the doctrine of Christianity was infused into the mass of strange beliefs and superstitions. But even in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, after the new religion had become established in the land, its priests continued to employ the moving images as they had done in the churches of Italy. Similarly too, we find the sacred representations and religious rites within the churches giving birth to the mysteries and morality plays just outside which gradually spread to booths in the market places and roamed the countryside under the guidance of ambulant showmen. In the Provençal cribs, the Crèches parlantes of the southern cities at Christmas time, there are to-day many qualities remaining from these old mysteries; the large decorated stages, the technical devices, the transformations, the beautifully dressed, articulated dolls, the music and recitations.

One characteristic of the great French mitouries was the use, frequently and openly, of human actors along with marionettes. Many records of such performances have been preserved, among them a description of one celebrated annually at Dieppe on the first day of August by a company of clergy and laity supported by several figures set in motion by means of strings and counterweights. In the open space before the Church of St. James there was represented the Mystery of the Assumption. Four hundred personaggi participated and the marvellous spectacle attracted throngs of strangers to the city of Dieppe. Similar performances at Christmas, Easter, or at other times were given in all the larger cities of France, in Rouen, Lyons, Paris, Marseilles. The plays were of a religious character. Notable as late as the seventeenth century were the spectacles produced by the monks of the Order of Théatines with clever movable figures upon the presepio they constructed before their convent door. These monks won the favor of no less a personage than Jules Mazarin, who had them give performances in Paris.

But, as these religious puppets ventured out from the jeweled twilight of the cathedrals into the bright sunshine they were accosted by flippant crews of wanderers from the South, Pulcinella, Arlecchino, Dottore, Cassandrino, Columbine, and other protagonists of Italian puppet drama, exploring in their castelli the highroads and villages of a new country. The merry foreigners intermingled happily with the native fantoches; they altered their names and their natures with easy adaptability and upon the French puppet stage appeared in sprightly guise Polichinelle, Harlequin, Pierrot.

French theatrical puppets must have become established in the sixteenth century for we find them mentioned in a work entitled Serées published 1584, by Guillaume Bouchet, juge et consul des marchands à Poitier. Polichinelle first presented himself to the Parisian public about 1630 and although not yet at the height of his glory he was completely changed into a buffoon of Gascony. In 1649 the marionettes entered into the first permanent stage erected in Paris for the jeu des marionettes, by the side of the Porte de Nesle. The proprietors of this theatre were two brothers (or father and son as some prefer to consider them) from Bologna, Giovanni and Francesco Briocci, the name changed by the French to Brioché. It is said that Brioché first displayed his dolls to attract clients for himself as he originally plied the trade of dentist. At any rate Francesco carved the dolls and Giovanni improvised the dialogue in French interspersed with quaint Italian or Latin sayings. So amusing were these burattini that they became tremendously the rage. We find Brioché mentioned in the works of the academician, Perrault, and in 1677 Nicolas Boileau speaks of him as a well known figure in the Parisian streets, “Là non loin de la place où Brioché préside, etc.”

There is a well known story concerning Cyrano de Bergerac and a trained ape of Brioché, Fagotin by name. A contemporary account of the incident thus describes the animal: “He was as big as a little man and a devil of a droll. His master had put on him an old Spanish hat whose dilapidations were concealed by a plume: round his neck was a frill à la Scaramouche; he wore a doublet with six movable skirts trimmed with lace and tags,—a garment that gave him rather the look of a lackey,—and a shoulder belt from which hung a pointless blade.” One day Cyrano saw the monkey arrayed in this livery wandering and grimacing about the puppet booth. But the poet, whose sensitiveness had been the cause of many a duel, imagined that the poor animal was making faces at his large nose. He grew excited and drew his sword. Thereupon the monkey, for whom this was a well-rehearsed trick, drew forth his tiny wooden weapon in imitation. Cyrano was infuriated beyond reason and rushing at the creature he killed it with his sword. All Paris heard of the event and an anonymous pamphlet was published concerning it in 1655 called “Combat de Cyrano de Bergerac contre le singe de Brioché.”

Another amusing tale is told of an Italian showman, supposed to have been Brioché himself, who wandered into Switzerland where puppets had seldom been seen. There this venturesome fellow narrowly escaped being burned at the stake by the simple-minded inhabitants who swore they had heard the little figures jabber, hence knew they were little devils summoned by evil methods to do their master’s bidding. He, poor man, was compelled to save his life by stripping the puppets naked and displaying before his judges their small crude bodies of wood and rags and paper.

However, in France the puppet show gained such popularity and fame that in 1669 Brioché was summoned to the court to amuse the royal Dauphin, son of Louis XIV. Thus Polichinelle makes his bow in the palace as the records of the royal accounts attest: “A Brioché, joueur de marionettes, pour le séjour qu’il a fait à Saint Germain en Laye pendant les mois de septembre, octobre et novembre pour divertir les Enfants de France, 1365 livres.” The following year a French showman, Francesco Datelin, was similarly summoned to entertain the Dauphin with his puppets, “à raison de 20 livres par jour.” The royal interest in marionettes extended still farther for, some years later, Francesco Brioché and his little wooden figures were protected by a special order of the King himself to the Lieutenant General of Police. And indeed, they probably needed such protection, for their popularity seems to have stirred up enmity against them. Besides they were often meddlesome and impertinent and deserved the wrath they incurred.

Under such favorable conditions companies of marionettes sprang up all over France. They attracted the attention of many writers of the day in whose works we may find them often and favorably mentioned, Gacon, Scarron, La Bruyère, Lemierre, Arnaud. Most ambitious among the immediate successors of the Briocci was the French showman, Bertrand, with his audacious puppets who never hesitated to poke their wooden noses into matters of gravest import. The revocation of the Edict of Nantes furnished one well known occasion. The puppets took sides, representing Catholics and Protestants upon their little stages. Pantalone was in one faction, Harlequin in another and Polichinelle, as Ferrigni describes him, “always something of an unbeliever, is ready at all times to pour ridicule upon the hypocrisy of bigots and the libertism of reformers.” The play drew crowds of all classes until it was finally stopped by the authorities who had been notified of it in this manner: “To M. de la Raynie, Councillor of the King in Council. It is said this morning at the Palace that the marionettes at the Fair of Saint Germain are representing the destruction of the Huguenots and, as you will probably find this a serious matter for the marionettes, I have deemed it right to give you the information thereof so that you may make use of it according to your discretion.” But despite an occasional rebuff, the marionettes became more and more firmly established in the two Fairs of Saint Laurent and Saint Germain. What clever shows, what ingenious and indefatigable showmen! Bienfait, Gillot, Tiquet, Maurice, De Selles, Francesco Bodinière, the brothers Ferron at The Sign of the Giglio, the Théâtre des Pygmées of La Grille, the show in the Rue Marais du Temple, Il Gallo and many others.

Now indeed the emboldened fantoches began to wage a most amazing battle royal, their opponents being no other than the managers, actors and singers of the contemporary stage. The three great theatres alone at this time had the privilege of representing musical opera, tragedy, or commedie nobili. The puppets were restricted to mere farces of one scene for not more than two characters, only one of whom was allowed to speak and that “par le sifflet, de la pratique,” a little contrivance which the showman put into his mouth when reciting to produce the shrill squeak characteristic of Polichinelle from time immemorial. But these showmen circumvented such limitations with many devices,—pantomimes with musical interludes and figures with printed cards hung up to explain the action, even living children combined with puppet play.

The large marionettes of La Grille, manipulated by wires sliding on rails and held upright by weights and counterweights, were claimed by their owner to be a new invention, despite the fact that similar dolls were not unusual in Italy. At any rate they were a novelty in France and to them King Louis XIV accorded special privileges. Nevertheless before long they had over-stepped them and trespassed upon the rights of the actors of the opera. The latter complained to the King. He issued fresh interdictions. The marionettes subsided: only to break forth again. In 1697 the Italian actors in the Hôtel de Bourgogne incurred disfavor at court and were temporarily put out of their theatre. Bertrand immediately installed his puppets in triumph upon their vacated stage which he, in turn, was eventually enjoined to quit by a subsequent order of the King. Thus the struggle continued.

In 1720 further privileges were obtained by the marionettes, six or seven at a time being allowed to sing, dance or recite upon the stage. Immediately the famous showman, Francisque, engaged three prominent poets to write new plays for his burattini, Fuzilier, Lesage, and d’Orneval. They set about creating a quite new form of dramatic art, a master stroke which has persisted ever since, the well known opéra comique. The first one, L’ombre du cocher poète, was given in a booth in the Foire Saint Germain and was so enthusiastically received that the jealous antagonism of directors and singers of the opera was aroused more violently than ever, but the opéra comique remained popular. Piron composed for the burattini an opéra bouffe, La Place, Dolet, Carolet, all invented puppet parodies on the plays and actors of the day. Favert composed his first drama for the pupazzi and Valois d’Orville inaugurated the Revues de fin d’année, a criticism of the year’s dramatic production by the mocking marionettes.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are quite rightly called the golden age of marionettes. The puppets were executed and managed with utmost skill, the mise-en-scène imitated the magnificence of the larger theatres. The greater the impertinences the greater the popularity of the puppets,—what wonder that the Comédie Française complained of them as a “concurrence déloyale.” But with the entrance into the puppet shows of the spectacular, the decline of the French marionettes began. It is true that despite his crude and rather broad repartee so popular in the two fairs, his jokes of doubtful taste relished upon the boulevards, Polichinelle continued to be the vogue among the upper classes. He was called to perform in the salon of the Duc de Bourbon, of the Duc de Bourgogne, of the Duchesse de Berry, and of the Duc de Guise at Meudon. At one time, indeed, the Duchesse de Maine had a puppet stage built at her chateau of Sceaux and plays and epigrams written for it by her friend and secretary, the academician Malezieu, which finally involved an altercation between Polichinelle and the Academy. At the same Castle of Sceaux in 1746 the Comte d’Eu had a company of marionettes brought in and he operated and spoke for them himself. Voltaire, present at this occasion, forgot his quarrel with the burattini for having poked fun at his Mérope and Oreste and took a hand himself at the manipulating. Eventually he found himself composing for them and inviting them into his own castle, Cirey, where he may have learned many things about the traditional Italian drama from studying the personaggi of the puppet stage.

At this time, indeed, Fourre, Beaupré, Audinot, Nicolet and Servandoni were making lasting names for themselves as directors of marionette theatres but it gradually came to pass that, as the audiences grew cold, witty jests were replaced by spectacular surprises such as the mechanical triumphs achieved by the puppets of Bienfait. We read of M. Pierre’s show. “Here are to be seen in every detail, mountains, castles, marine views; also figures that perfectly imitate all natural movements without being visibly acted upon by any string, storm, rain, thunder, vessels perishing, soldiers swimming.” We hear of Audinot’s exhibition of life-sized bamboches imitating with striking resemblance celebrities of the day, displaying the follies and vices of the eighteenth century courts. Children were seen acting with puppets and there were innumerable military pieces such as, The Bombardment of Antwerp, or The Taking of Charleroi. Poor Polichinelle, indeed! We will scarcely be surprised to find him struggling along as best he can and finally suffering a last indignity by losing his little wooden head for the edification of the Parisian mob on the very day, at the very hour, when the unfortunate monarch Louis XVI was guillotined.

Everywhere puppets have originated among the common people: they are primarily an expression of popular taste. Nevertheless, this rude show of the masses has frequently aroused the curiosity of artists and some of them have found in the very naïveté of the dolls unexpected artistic possibilities. The delightful potentialities have been developed into an exquisite and unique art genre in many countries, particularly in France.

We have seen the kings and courts entranced by the burattini of Brioché and his followers. Lesage, Piron and other dramatists were engaged in writing plays for the fantoches; even the great Voltaire entertained his distinguished guests at Cirey with his own puppet shows. Rousseau was interested in them. Gounod wrote “The Funeral March of a Marionette.” Charles Magnin, learned member of the Académie Française, devoted himself to the task of chronicling the long history of puppetry. Charles Nodier, persistent visitor of the Parisian shows, is called by some Polichinelle’s laureate for the many sparkling pages in his works that are devoted to the marionette.

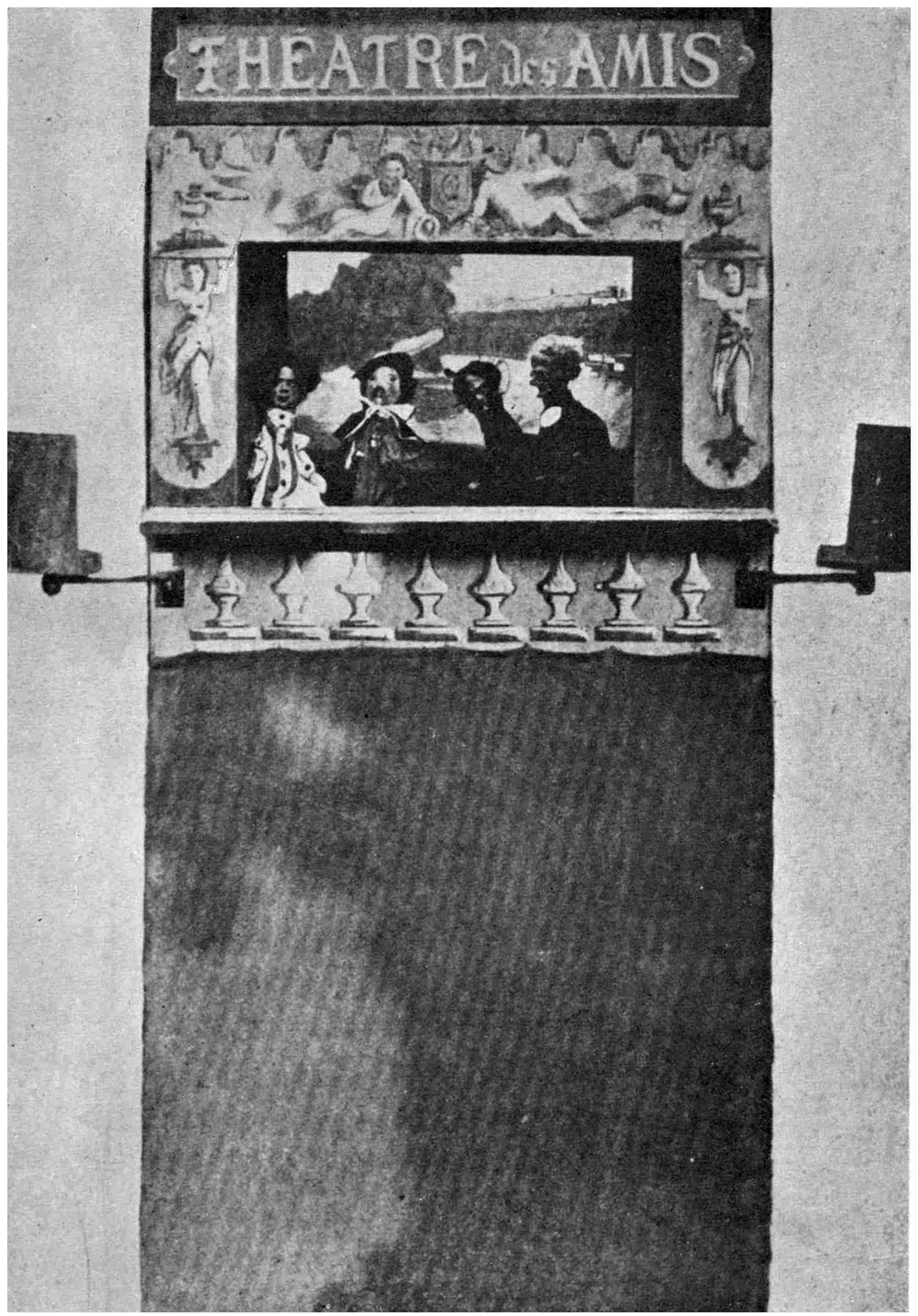

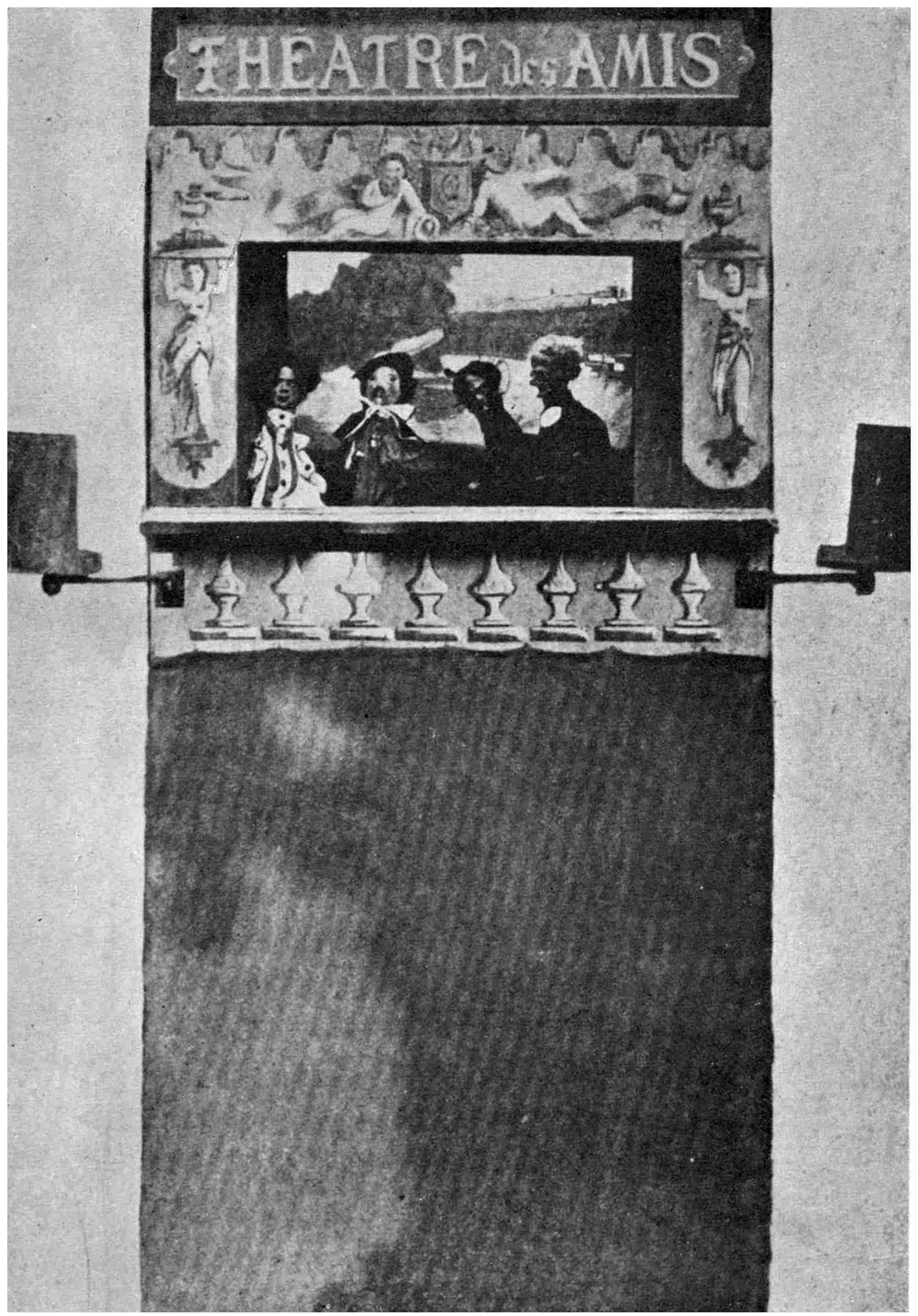

We shall not be so greatly surprised, therefore, to learn that George Sand had her own puppet theatre at her estate, Nohant, where for thirty years she herself arranged the plays and dressed the dolls while her son, Maurice, sculptured them and acted as director. It was called, Théâtre des amis and the first performance was given in 1847. This was a very crude affair got up by Maurice Sand and Eugene Lambert (painter of cats) for themselves and a circle of intimate friends. The stage itself was merely a chair with its back turned to the audience, a cardboard frame arranged in front of it with a curtain to be rolled up and down. The operator knelt upon the seat of the chair, on his hands were placed the puppets, which consisted merely of dresses hung upon sticks of wood for the head, scarcely carved at all. Being tremendously successful, this performance was followed by others. Thus the theatre grew.

GEORGE SAND’S PUPPET THEATRE AT NOHANT

[From Ernest Maindron’s Marionettes et Guignols]

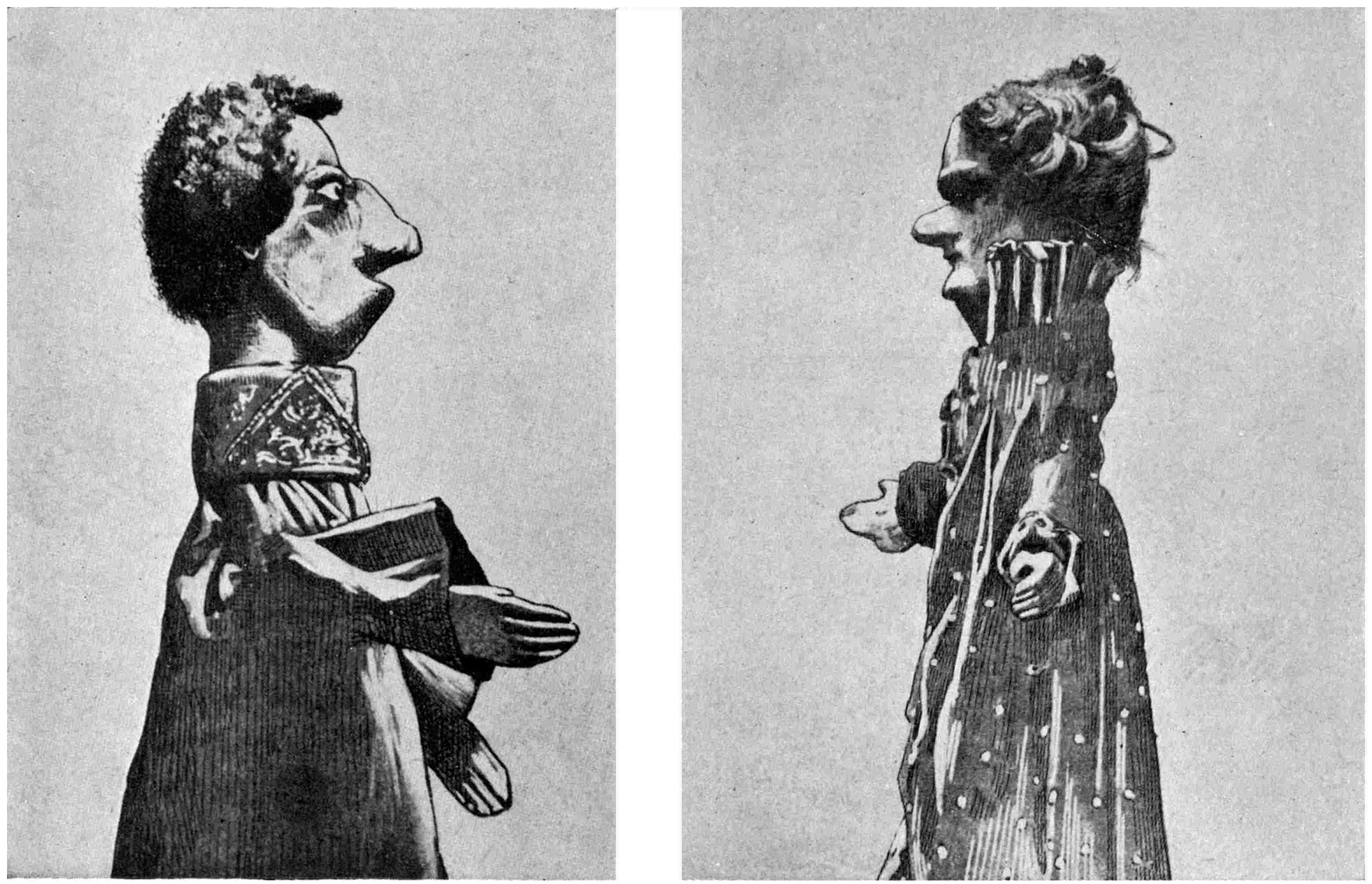

George Sand developed very decided theories about her little dolls. She writes that she prefers the sort which may be manipulated on three fingers to those moved by means of wires. Her feeling was that when she thrust her hands into the empty skirts of the inanimate puppet it became alive with her soul in its body, the operator and puppet completely one. She disapproved of realistic puppets. The faces of her dolls were carved with great skill but purposely left crude, painted in oil without varnish to get the strongest effect, with real hair and beards and special attention given to getting light into the eyes. There were, eventually, over one hundred dolls including such as Pierrot, Guignol, Gendarme, Isabelle della Spade, Capitaine, also well known types and personages of the day. Very popular and subsequently famous was the Green Monster at Nohant. It appears that in one of the early plays the cast called for a green monster. Upon the maker of the marionettes devolved the task of supplying one. Madame Sand, nothing daunted, discovered an old felt slipper. By using the opening as the wide jaws of the dragon and lining it with red to represent the inside of the mouth, a very effective, long snout was presented which, with a hand slipped inside, could be opened and closed most fearfully and threateningly. It was a highly successful green monster. Whenever it appeared there was much applause, and nobody ever seemed to notice or to care that it had been manufactured out of blue felt.

The repertoire of the Théâtre des amis was varied, sometimes fantastic whimsies, sometimes travesties on daily events; sometimes the managers grew ambitious and presented spectacular scenes with ballets; the literary side of the production was always emphasized. These shows, the best of their sort, continued through most troublesome times of political upheaval and George Sand has written some touching paragraphs upon the fact that hearts sorely grieved by these national trials, could find distraction and a moment’s respite with the marionettes.

The puppets, too, had their vicissitudes. At one time, Victor Borie, who was assisting, in attempting to represent a fire, burnt down the whole stage. It was built up anew with more puppets and better equipment. Madame Sand dressed the new dolls as she had the old. More helpers had to be called in, all talented persons who entered into the work with enthusiasm. The audience always contained celebrated people, representatives of literature, art, music and statesmanship. Once when the puppets presented a parody upon La Dame aux Camellias (presumably not for young ladies) Dumas, fils, came to see and enjoy the production. In 1880 the puppets moved from Nohant to Passy to the home of Maurice Sand, where a large theatre had been prepared for them. Here there were over four hundred elaborate dolls. But in 1889 Maurice Sand died and the Théâtre des amis disappeared. A book written about it was published in 1890.

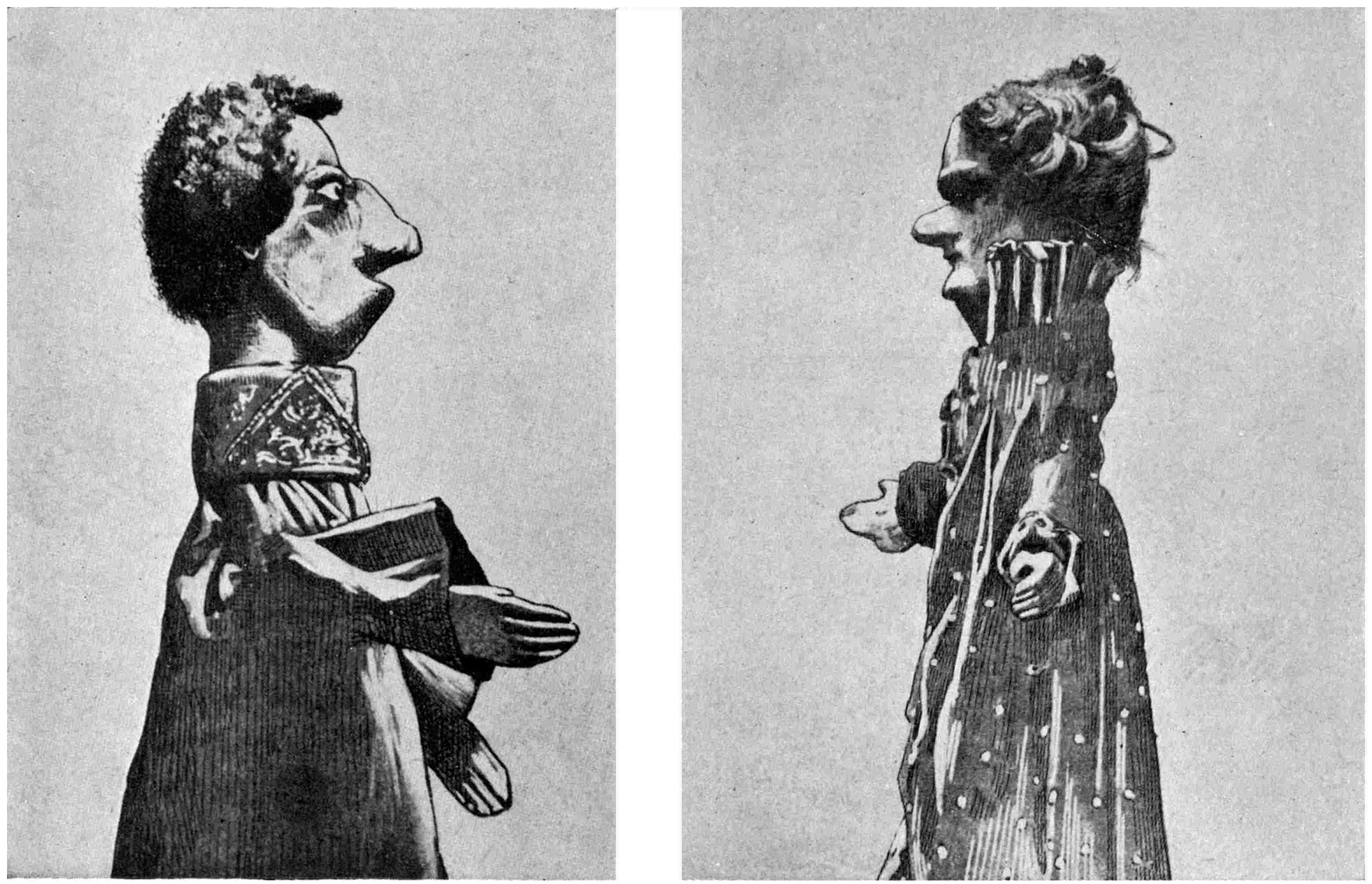

PUPPETS OF GEORGE SAND’S THEATRE AT NOHANT

[From Ernest Maindron’s Marionettes et Guignols]

Equally illustrious and possibly more exquisite, more precious, were the puppets of the Erotikon theatron de la rue de la Santé, established in 1862. Here it is said puppetry was raised to an ideal level. Here, an enthusiastic press of the day proclaimed, here was the proof of how highly developed a naïve and simple art may become in the hands of rare spiritual and æsthetic personalities. Another journal, Le Boulevard, exclaimed, “Again a new theatre! An intimate theatre, Erotikon theatron, that is to say Theatre of Amorous Marionettes. Reassure yourselves, everything that transpires is most conventional; the blows of the cudgel are always protectors of morality and if a mother would not see fit to bring her daughter, on the other hand, painters and literateurs of talent take delight in it.”

It was indeed an exceptional experiment, a gathering of artists, sculptors, musicians, actors, authors; Lemercier de Neuville, the guiding spirit, assisted in his efforts by Carjat and Gustave Doré, and also by Amedée Rolland, Jean Dubois, Henri Monnier, Théodore de Banville, Bizet, Poulet Malasses, Champfleury, Duranty, Henri Dalage and others, each contributing something toward the perfection of the whole. M. Lemercier de Neuville was in the beginning architect, mason, painter, machinist, carpenter, decorator, hairdresser and tailor, actor, singer, dancer and imitator. Alfred Delvau has written an entertaining history of this bizarre little theatre. The project seems to have been suggested informally at the home of M. Amedée Rolland, by a group of distinguished men of letters who had been lunching together, among them De Neuville, who proceeded to transform the idea thus lightly suggested into a concrete reality.

The auditorium seated only twenty people; its walls were painted with mural decorations by artists of the group, as was the proscenium arch of the stage. The stage itself was only a trifle over two yards wide, but it was well equipped for the presentation of quite elaborate faeries. For the most part, however, there were merely the pupazzi upon the stage, which M. de Neuville worked himself upon his fingers. Their faces were modelled with unsurpassed refinement and animation, their creator having lavished his heart and talent in the making of them. His Pierrot Guitariste was, according to Maindron, the most charming of all puppets, in gesture and bearing a masterpiece of mechanical and plastic art. Others have called it the most highly perfected puppet ever created. Another remarkable doll was the violoncellist who could enter, bow in one hand, instrument in the other, seat himself, tune up and play. There was a Spanish dancer particularly graceful and alluring as well as a wonderful ballet, worked on one horizontal string, which glided in and out and back and forth. Sarah Bernhardt was represented among these fascinating pupazzi and Jules Simon, Coquelin, cadet, and other celebrities familiar in Paris. As de Neuville lived among the individuals he was representing what wonder that his mimicry was close to perfection?

This altogether rare little theatre unfortunately endured for only a year and produced in all but six or seven delightful if slightly shocking pieces, although more had been written for it. Perhaps the dissimilarity of talents comprising it was too great, but at least its inspired cynicisms, amusing audacities and exquisite spectacles have won the lasting acclamations of the French press, of royalty and of the greatest geniuses of the day.

SIVORI COQUELIN CADET PIERROT GUITARISTE

Puppets of Lemercier de Neuville, Erotikon theatron de la rue de la Santé

[Reproduced from Ernest Maindron’s Marionettes et Guignols]

In the shadow play, as well as in the play of pupazzi, French artists have attained great successes. The first Ombres Chinoises, so called, of importance started simply enough about 1770 when Dominique Seraphin, a young man of twenty-three, established his little show in Versailles. In the beginning for the amusement of children, little comical dialogues such as The Broken Bridge, or The Imaginary Invalid (from Molière), were presented by silhouette figures with articulated limbs. In 1774 after a few years of unusual success, Seraphin moved to Paris where, under royal protection, his little shadows became very well established. Although they had been ensconced in the Palais Royal by favor of the king yet they managed through the cleverness of Seraphin to sustain themselves in popular favor after the overthrow of royalty. Indeed they were said to be the first to avail themselves of advertisements in the form of posted placards.

The advertisement was rather charming:

“Venez, garçon, venez fillette,

Voir Momus à la silhouette.

Qui, chez Seraphin, venez voir

La belle humeur en habit noir.

Tandis que ma salle est bien sombre

Et que mon acteur n’est que l’ombre

Puisse, Messieurs, votre gaîté

Devenir la réalité.”

Long after the death of Seraphin, until 1870 in fact, the show continued in the hands of his descendants, presenting pieces especially written for it, with music composed to accompany the shadows.

It was the art critic, Paul Eudel, who first published an illustrated volume of such fairy pieces and melodramas composed by his grandfather in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Half a century later Lemercier de Neuville, who was interested in pupazzi noir as well as in other puppets, published another collection of little plays with fifty illustrations and with explanations of designs and methods of producing the shadows. De Neuville had enlarged the scope but had not changed the principles of the art. He presented animals who opened their jaws, processions and caricatures of celebrities such as Sarah Bernhardt, Zola, and others.

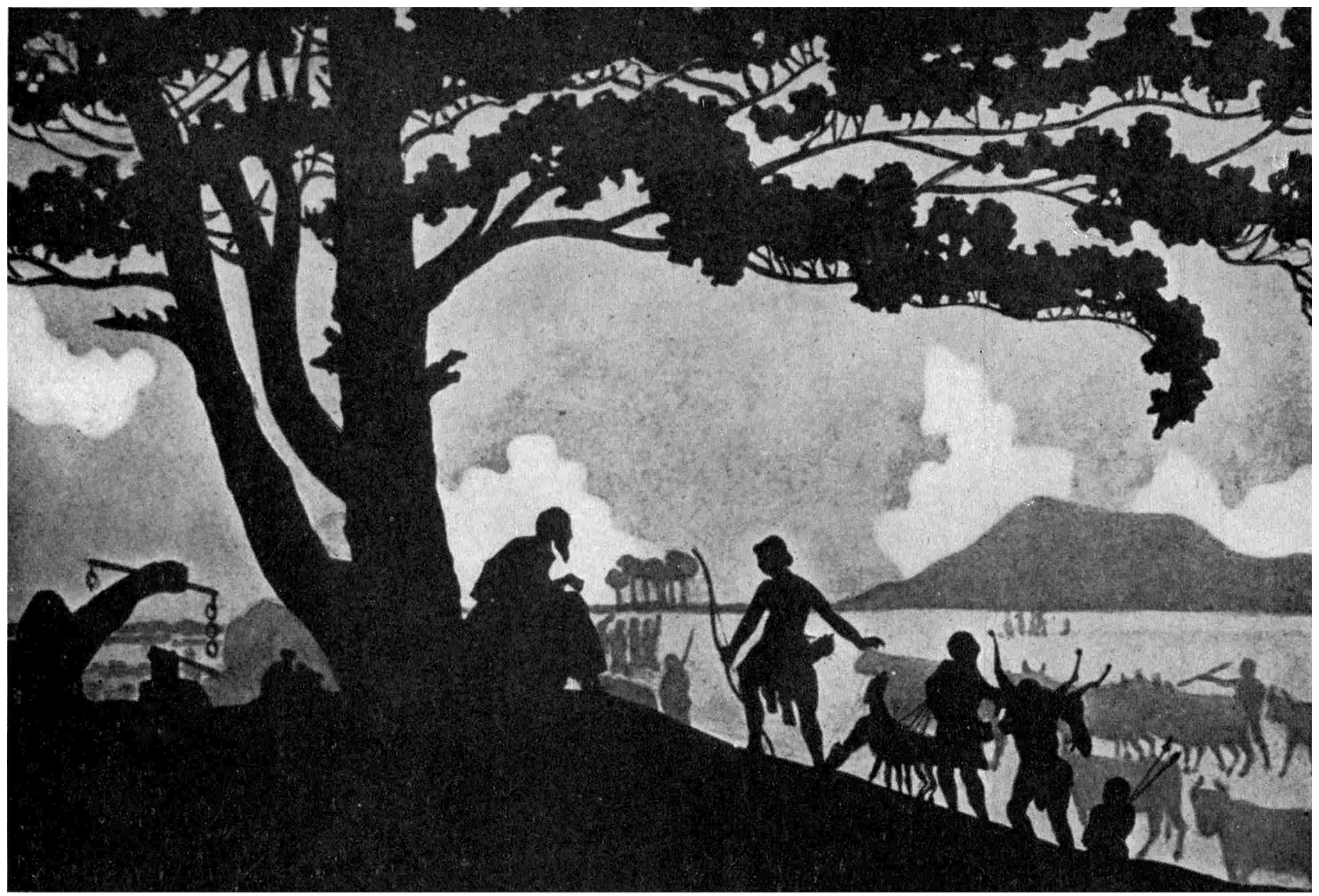

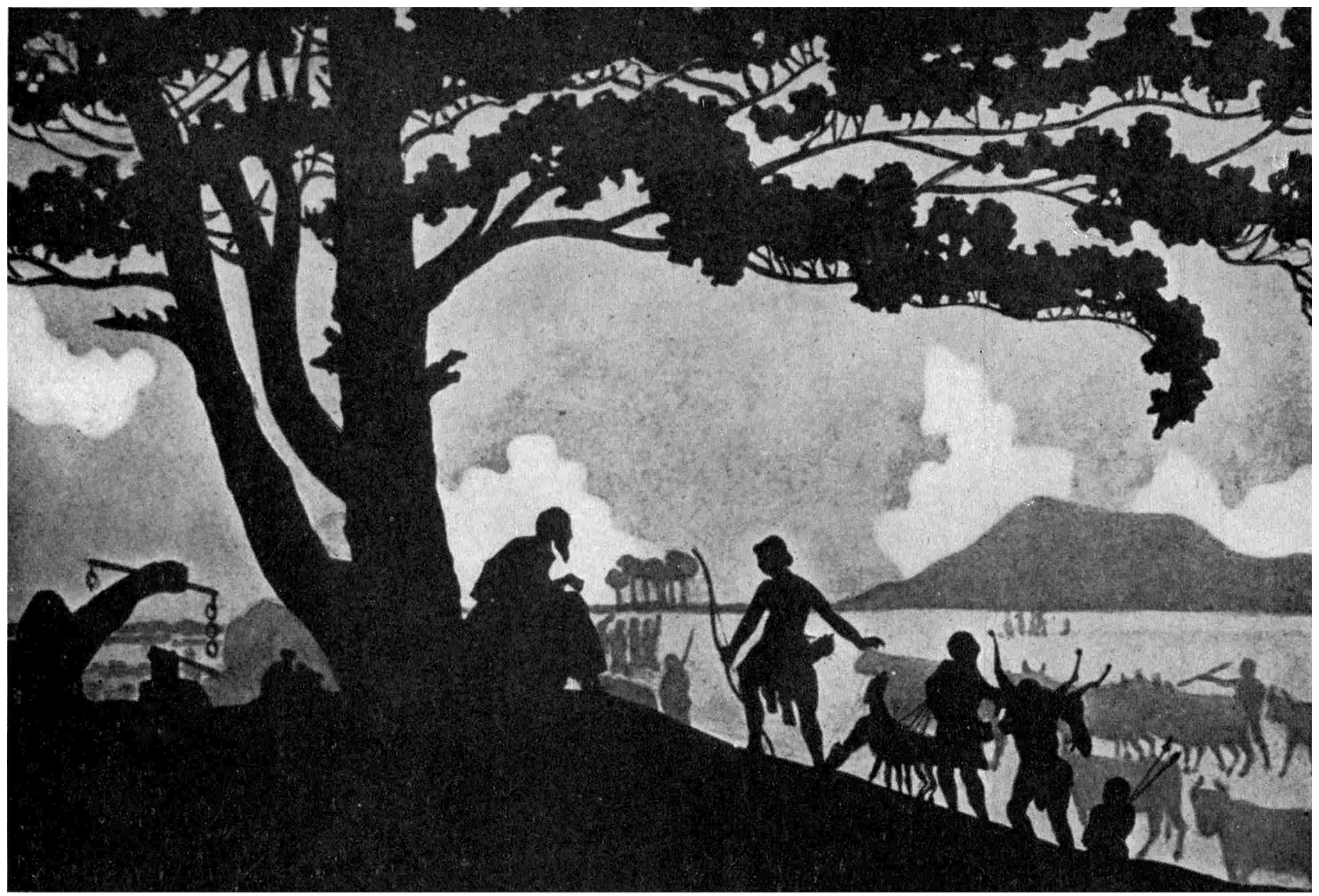

TABLEAU

From a shadow play of The Prodigal Son at the Chat Noir

[Designed by Henri Rivière]

Then a little later came the wonderful shadows, now designated as Ombres Françaises, and shown at the Chat Noir, famous cabaret of Montmartre where gathered literary and artistic Bohemia. “The Chat Noir has an art of its own,” writes Anatole France, “that is at once mystic and impious, ironical, sad, simple and profound, but never reverential. It is epic and mocking in the hands of the precise Caran d’Ache. It has a bland and melancholy viciousness in Willette, who is, as it were, the Fra Angelico of the cabarets. It is symbolic and naturalistic with the very capable Henri Rivière. The forty scenes of the ”Tentation“ of St. Anthony amaze me. They exhibit lovely coloring, daring fancy; impressive beauty and forcible meaning. I put them far above the imps depicted by the austere Callot.” These comedies, spectacles, military epics, oratorios, mysteries, Greek scenes, burlesques and pantomimes, were indeed conceived with a certain large poetic glamour. It was Caran d’Ache who made the great artistic contribution of giving up articulation of individual figures, for the most part, to move great numbers of them along. He invented perspective in shadows, using masses of figures in different planes and producing a sense of solidarity and immensity. His masterpiece, Epopée, the evocation of the Grand Army of Napoleon, presented with epic grandeur company after company of cuirassiers in long lines, the profiles diminishing in height as the figures receded from the eyes. It conveyed, as one critic avers, the idea of great space and of a vast army of men marching in serried ranks “to victory or to death.” A few single figures were allowed to stand out distinctly like the Little Corporal on horseback, there was little speech only music and an occasional command. The effect of this military silhouette was most impressive.

Next came Henri Rivière, who added the variety of color to the shadows, and furthermore, by the use of two magic lanterns, created dissolving views so that the background might be altered at will. The subjects of his elaborate pantomimes were such as The Wandering Jew, The Prodigal Son, and The Temptation of St. Anthony. Of the latter, Rehm has given us an admiring appreciation. “We saw the sun setting into the sea, the forests trembling in the morning breeze; we saw deserts stretching out into the infinite, the oceans surging, great cities flaming up in the evening with artificial lights and the moon silvering the ripples of the rivers upon which barges were silently and slowly gliding along. He (Rivière) employs everything from the picturesque style of watercolor spread on with a brush to the imitation of Japanese color prints, pen sketch and poster style, Gothic or Pre-Raphaelite characteristics and naturalistic impressionism. In The Sphinx where the conquerors of all centuries, from the Pharaohs to Napoleon, file past this monument of eternity; in his March of the Stars where shepherds and their flocks, beggars, slaves and fishermen, and the Wise Men from the East make their pilgrimage to the Virgin with the Divine Child; in the Enfant Prodigue where the son of the patriarch sets out for Egypt accompanied by his herds, his caravan, his riders,—to return, a beggar,—everywhere we see this art, dreamlike and philosophic, legendary, fantastic, sublime, creating ecstatic illusions.” Of The Sphinx, a collaboration of Rivière and Caran d’Ache, Jules Lemaître writes, “Here we have a true epic poem, simple yet g