Puppet Shows of Germany and of Other Continental Countries

PERHAPS it was the luxuriant forests of Germany offering abundant material and opportunity which encouraged the native aptitude, at any rate the inhabitants of the land have at all times been noted for their skill in wood carving. Moreover they appear to take a certain delight in mechanical devices. From very early times these interests were applied to the making of mechanical toys and dramatic puppets.

In the dark ages we find the people of the country carving a grotesque sort of wooden doll, called Kobold or Tattermann which they set up in the chimney and worshipped as a heathen household deity. Later these little figures came to be worked by wires. As far back as the twelfth century and according to Charles Magnin even in the tenth century, the word Tocha or Docha was used to signify a kind of puppet. One of the earliest Minnesingers mentions Tokkenspil in his poem and another speaks of the Jongleuren attracting their audiences by displaying little dolls which they pulled out at any time from under their mantles.

The subject of the early Tokkenspiel seems to have been gathered chiefly from the legends of the Edda, and from the Hildebrandslied and the Niebelungenlied. Praetorius mentions: “Foolish jugglers’ tents where old Hildebrand and such Possen are played with Dokken, called puppet comedies.” Later the mystery play appeared and the automatic Kruppenspiel, religious drama here as elsewhere opening up a path for the profane. These plays were founded upon such themes as, The Fall of Adam and Eve, Goliath and David, Judith and Holofernes, King Herod or The Siege of Jerusalem.

Of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries we have little positive data. Romantic subjects appear to have been used for the puppets, also history and fable such as The Four Sons of Aymon, Genevieve of Brabante, The Lady of Roussillon, and even Joan of Arc which was quoted in another piece performed in 1430.

Invariably the comic element appears in the puppet shows of all nations. In Germany and Austria the buffoon has always been a part of even the most tragic dramas, lending variety and relief by his good natured, if somewhat obvious jests. The first names by which he was known in Germany may have been Meister Eulenspiegel or Hemmerlein, later it became Hanswurst and Kasperle. The name Kasperle, so Rabe claims, came through Austria and Professor Pischel goes still further in his assertion that the prototype for Kasperle was brought into the land over two thousand years ago from India. Later, of course, Italian and French players introduced Pulcinella and Arlecchino with their merry company.

In Hamburg puppets have been popular from earliest times. It was in 1472 that a showman announced The Public Beheading of the Virgin Dorothea. This theme remained a favorite in the puppet plays of that city for centuries, while the long suffering martyr continued to be ever more and more elaborately but neatly beheaded, in full view of the audience. In the eighteenth century an announcement proclaimed: “Exceptional marionette players with large figures and, accompanied by lovely singing, the execution of Dorothea.” The play of The Prodigal Son was another great favorite. It gradually lost its religious character and became a rather gruesome affair producing with ingenious mechanical appliances metamorphoses of which the country has always been particularly fond. For instance, Reibehand, a tailor who set up a booth in the horse market of Hamburg, advertised in 1752: “The Arch-prodigal chastened by the four elements, with Harlequin a joyous companion of the great criminal.” This extra-moral piece, given in great style, displays the prodigal about to partake of fruit which turns into skulls in his hands, then water becomes transformed into fire, rocks rend apart disclosing a corpse hanging from a gallows. As it swings in the wind, the limbs fall off and then collect again, on the ground, and arise to pursue the prodigal, and so on with similarly pleasing surprises.

In 1688 another showman, Elten, advertised Adam and Eve and following it Jackpudding in a Box and later another announces: Elijah’s Translation into Heaven, or The Stoning of Naboth, followed by a farce, The Schoolmaster Murdered by Jackpudding or The Baffled Bacon Thieves.

There had been in Hamburg, however, French marionette troupes which gave very artistic puppet operas based upon mythological subjects, such as Medea, including in one of its casts a puppet who smoked! These plays were produced in combination with acts by living actors, jugglers, acrobats, and trick horses.

As far back as the sixteenth century scepticism and sorcery had become the order of the day with the Germans who have naturally a tendency toward philosophical reflections, as well as a leaning toward the occult and supernatural. It was then that Faust, embodying both of these tendencies, first appeared upon the puppet stage, with most significant consequences for German literature.

This puppet play might be sufficiently interesting in itself, but the fact that it became the inspiration for one of the world’s greatest dramas may lend an added justification for pausing a moment to trace its curious history. Early in the sixteenth century it is said that the Tokkenspieler presented, at the Fairs, The Prodigious and Lamentable History of Doctor Faustus. In 1587 the famous Spiesische Faust Buch was published in Frankfurt and recorded the adventures of a semi-historical charlatan who had wandered through Germany in the early sixteenth century. He was famous not only for his skill in medicine but in necromancy and other similar arts. He may have been identical with Georgius Sabellicus who called himself Faustus Junior, implying that there had been a still earlier Faust. He may possibly have been the Bishop Faustinus of Diez, seduced from the right path by Simon Magus, or the printer of Mainz, Johann Faust, who was declared to have been a sorcerer. Whoever he was, the disreputable conjurer tricked fate into granting him an immortal name. In 1588 two students of Tübingen and a publisher were punished for putting forth a puppet play based upon this Spies book. There are other versions of the Faust puppet show, that played at Strassburg, that of Augsburg, of Ulm and of Cologne, each varying slightly from the others. They were all first produced about the time of Marlowe’s famous drama on the same theme or only a trifle later.

The story of the Faust play has a tremendous appeal; it is a picture of man’s vain desires and vain regrets. We find the scholar Faust alone in his study, meditating over the wasted years of research and the wisdom of this world which is so limited at best. He turns to the black arts and summons up an evil spirit to serve him. In one version of the puppet play Faust calls up numerous devils and decides to select as his own particular servant the swiftest. Thereupon the evil spirits describe their speed. One claims to be “as swift as the shaft of pestilence”; the next is “as swift as the wings of the wind”; another “as a ray of light”; the fourth “as the thought of man”; the fifth “as the vengeance of the Avenger.” But the last, who is Mephistopheles, is as swift “as the passage from the first sin to the second.” Faust replies: “That is swift indeed. Thou art the devil for me.” Then he signs the pact with his blood. A raven flies in and carries away the message. Mephistopheles is bound for twenty-four years to provide Faust with all the pleasures of this world and also to answer truthfully every question asked him. In return Faust pledges his soul to the devil at the expiration of the time.

Mephistopheles carries Faust to the court of the Count of Parma where he entertains the count and countess with magical shows, calling up Samson and Delilah, David and Goliath, Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Throughout the play Faust is always taken seriously; Kasperle supplies the ludicrous element. His buffoonery is at times really amusing. As an assistant of Faust’s servant Wagner, he meddles with magic, on his own responsibility. Having picked up a few words of incantation, he uses them according to his own pleasure; but Kasperle is wiser than his master for he very shrewdly refuses to sign away his soul. However, he has discovered that by pronouncing the potent syllables “Perlippe” he can summon up demons and by saying “Perlappe” he can make them vanish. Thereupon he amuses himself (and the audience) by reciting “Perlippe, perlappe, perlippe, perlappe,” so often and in such quick succession that the poor demons get quite out of breath and very irritable.

In the last act we find Faust back after twelve years at his study in Wittenburg. He has had his fill of pleasures and is sick at heart and repentant. He asks Mephistopheles whether there would be a chance of a sinner like himself coming to God. Mephistopheles, compelled by his oath to answer truthfully, vanishes with a cry of terror which is an admission of the possibility. Faust, with new hope in his heart, kneels before the image of the Virgin in supplication. But Mephistopheles reappears with a vision of Helen of Troy to tempt Faust, who resists but finally succumbs. Forgetting the Virgin he rushes out with Helen in his arms. Immediately he returns and reproaches Mephistopheles for deceiving him, because the vision has turned into a serpent in his embrace. “What else did you expect from the devil?” asks Mephistopheles.

Faust realizes he is lost. Moreover his time is up, for the devil having served him both night and day considers that he has done twenty-four years work in twelve. Wandering the streets in despair Faust comes upon Kasperle, now the nightwatchman, and tries naïvely to cheat the devil by offering Kasperle his own coat. But the shrewd fellow is too keen to be thus taken to eternal torture in another’s place. Ten o’clock strikes, then eleven. “Go,” says Faust to Kasperle, “go and see not the dreadful end to which I hasten.” Kasperle goes out. Twelve o’clock strikes and Faust hears the terrible sentence pronounced upon him: “Accusatus est, judicatus est, condamnatus est.” The fiends appear amidst flames and smoke and drag him away to his horrible fate. Kasperle returning and finding him gone, exclaims: “Poof! What a smell of brimstone!”

Even the briefest review of the plot cannot fail to move one somewhat for there is in this crude puppet show a deep and general human appeal. An earnest and anxious man to whom life has not been over-kind stakes all in his eagerness and craving for truth. Despite the naïve superstitions and the childish humor scattered throughout the play the tragic seeking of a human soul, the struggle between Mephistopheles and Faust demands our sympathy. In this respect there is more dramatic intensity and more human interest to the puppet show than one finds in either Marlowe’s play or even Goethe’s. In the former Faust is pictured with a desire to possess and we know that he is lost from the beginning; in Goethe’s drama Faust is consumed with a desire to live and we know throughout that he will be saved by his very struggles. In the puppet play Faust is finally condemned, but until the very end, by Mephistopheles’ own admission, he might have been saved.

The play was tremendously popular all over Germany. In 1705 the puppets got themselves into trouble with the clergy by a performance brought from Vienna to Berlin where it was announced, Vita, Geste e Descesa all’ Inferno del dottore Giovanni Faust. Because of the storm of approval aroused by the impious passages in the drama the performance was finally prohibited in Berlin. But elsewhere productions of Faustus flourished. In 1746 in Hamburg an amusing announcement proceeded to allay the fears of timid folk in the following manner: “History of the Arch-sorcerer Doctor Johannes Fauste. This tragedy is presented by us, not so fearfully as it has been previously by others, but so that everyone can behold it with pleasure.”

Half a century later Schutz and Dreher, very successful showmen of Berlin with a splendidly equipped puppet stage, presented among numerous old pieces of knightly romance, mythology and biblical legend, the tragedy of Faust. It was acclaimed by high and low. Then Geisselbrecht, a rival showman of Vienna, strove to outdo this production and gave an elaborate Faust play with little figures whom he made lift and cast down their eyes, even cough and spit very naturally,—a feat which Kasperle was nothing loath to perform over and over again as we may imagine. It was this very Geisselbrecht who served as a model for Pole Poppenspäler, the delightful little novel which Theodor Storm has written around the figure of a wandering puppet showman. Geisselbrecht toured with his puppets and gave performances all over the country, in Frankfurt among other places. The crowning significance of his Faust production was the fact that young Goethe, who was very fond of puppet shows, is supposed to have seen this play and to have drawn from it the first inspiration for his masterpiece, Faust.

In his childhood Goethe had always manifested great interest in toy theatres and puppets. At twenty years of age he wrote for his own amusement, The Festival of Plundersweilen, a satire on his audience of friends and family to be performed by marionettes. Later he perfected it and produced it on a puppet stage specially erected for the purpose at Weimar. There also he composed another puppet play to celebrate the marriage festivities of Princess Amelia. Both of these dramas are included in his works. In Wilhelm Meister and in the Urmeister we find many paragraphs devoted to the toy theatre of his childhood. But more important than this was the contribution of the little Puppen toward his immortal Faust. They not only suggested the theme but offered models for the treatment of it which Germany’s great genius was not too proud to follow.4

The unprecedented prominence of the Puppenspiel during the seventeenth century was brought about by the long theological strife between the clergy and the actors of the legitimate stage. The preachings and denunciations of Martin Luther had put an end to dramatic church ceremonies of which there seem to have been many. It went so far that the ministers refused to administer the sacraments to actors. The latter protested and appealed, but the people were restrained through their fear of the Church. Consequently the profession fell into such disrepute that the number of regular theatres rapidly decreased and troupes were disbanded, while the humiliated and neglected players were forced to join puppet companies and read for the marionettes to earn a living.

It was a great opportunity for the marionettes. After the Thirty Years’ War showmen came into Germany from England, France, Holland, Italy, even from Spain. To add to the attraction of their productions they combined with the plays dancers, jugglers, trained bears and similar offerings. In 1657 in Frankfurt Italian showmen established the first permanent theatre for puppets. In 1667 a similar theatre was erected for marionettes in the Juden Markt of Vienna where it remained for forty years. In Leopoldstadt in the Neu Markt Pulzinellaspieler gave performances in the evenings except Fridays and Saturdays, after angelus domini. Even the Emperor Joseph II is said to have visited this Kaspertheater in Leopoldstadt.

A curious dramatic medley began to be presented. “At the end of the seventeenth century,” writes Flögel, “the Hauptundstaatsactionen usurped the place of the real drama.” These were melodramatic plays with music and pantomime, requiring a large cast composed partly of mechanical dolls, partly of actors. It was only timidly that the actors thus ventured to return to the stage in the rôles of virtuous people (to be sure of the sympathy of the audience). The famous showmen Beck and Reibehand were noted for these performances, the subjects of which were martyrdoms of saints, the slaughter in the ancient Roman circuses and the gory battles of the Middle Ages (in all of which, needless to say, the puppets performed the parts of the slaughtered and martyred, as when the ever popular Santa Dorotea was decapitated and applauded so vigorously that the showman obligingly stepped out, put the head back on the body and repeated the execution). In 1666 in Lüneberg, Michael Daniel Treu gave the following Demonstratioactionum: “I: the History of the city of Jerusalem with all incidents and how the city fell is given naturally with marvellous inventions openly presented in the theatre; II: of King Lear of England, a matter wherein disobedience of children against the parent is punished, the obedience rewarded; III: of Don Baston of Mongrado, strife between love and honor, etc., etc.” Then there followed in the list of plays Alexander de Medici, Sigismundo, tyrannical prince of Poland, the Court of Sicily, Titus Andronicus, Tarquino, Edward of England and, of course, Doctor Johanni Fausto, Teutsche Comedi (to distinguish it from Marlowe’s tragedy).

When one considers that these plays with all the necessary business were long and complicated, one may imagine the difficulty of the art of puppet showmen. Everything connected with the presentation, the settings, directions and the plays themselves had to be learned by heart. Young boys generally attached themselves to showmen as apprentices and observed and studied for years before they were even allowed to speak parts. These had to be acquired by listening, for although the owner of the puppets generally had a copy of the play it was so precious a possession that he guarded it most carefully.

The amazing repertory of the Puppenspiel during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ranged from myth and history to any event of the day of intrinsic interest. In 1688 we find the marionette manager, Weltheim, giving translations of Molière, also the old Adam and Eve followed by a buffoonery called Jack Pudding in Punch’s Shop and the strange assortment of Asphalides, King of Arabia, The Lapidation of Naboth, The Death of Wallenstein. Weltheim used students of Jena and Leipsig to read for his puppets.

When in 1780 Charles XII of Sweden fell dead in the trenches of Friedrichschall, slain (so popular tradition averred) by an enchanted bullet, his death was immediately dramatized and produced on the puppet stage. In 1731 the disgrace of Menschikoff was made into a drama performed in German by the English puppets of Titus Maas, privileged comedian of the court of Baden Durlach,—“With permission, etc., etc., there will be performed on an entirely new theatre and with good instrumental music, a Hauptundstaatsaction recently composed and worthy to be seen, which has for title—The Extraordinary vicissitudes of good and bad fortune of Alexis Danielowitz, Prince Menzikoff, great favorite of the Czar of Moscow, Peter I of glorious memory, to-day a real Belisarius, precipitated from the height of his greatness into the most profound abyss of misfortune; the whole with Jackpudding, a pieman, a pastry-cook’s boy and amusing Siberian poachers.” Although Titus Maas had permission to perform in Berlin his show was quickly stopped for political reasons.

The undisputed predominance of puppets upon the German stage gradually subsided in the eighteenth century as Gottsched and Lessing revived the art of poetry and drama. The actors assumed their own place in the theatre; the Puppen returned to a more modest sphere. But they continued to be popular. After Schutz und Dreher in Berlin came Adolf Glasheimer’s humorous satires of which the hero was Don Carlos, with Kasperle to amuse the children, the whole arrangement conducted in connection with a Conditerei. In 1851 a revival of marionettes in cultural circles occurred and people streamed to see the clever show in Kellner’s Hotel at Christmas time. Richter, Freudenberg and Linde were three other favorite showmen of Berlin.

There had been, indeed, some very exclusive and artistic marionettes at the castle of Eisenstadt in Hungary. Here Prince Nicholas Joseph von Esterhazy had his own very elegant stage with dolls exquisitely perfect and magnificently dressed. He even assembled an orchestra for them, the leader of which was no other than Joseph Haydn himself. This great musician did not scorn composing symphonies for the puppets, The Toy Symphonies and The Children’s Fair, both charmingly playful compositions. He also wrote five operas for these distinguished marionettes, Filemon and Baucis, Genievre, Didone, Vendetta, The Witches’ Sabbath. But it was not his noble patron alone who influenced Haydn to compose for the puppets. Previously he had become interested and had written an opera called The Lame Devil for the burattini of an Italian puppet player, Bernardoni, in Vienna.

The marionettes have likewise attracted genius in other fields. The Romanticists, Arnim and Brentano, as well as the poets Kerner, Uhland and Mörike had interested themselves in shadow plays rather than puppet shows. But Heinrich Kleist wrote a very sympathetic and profound little essay called Concerning the Marionette Theatre. He seeks to discover the mysterious charm in puppet gesture and he suggests that the great dramatists must have watched the puppet plays with unusual interest and that artists of the dance might well learn the art of pantomime from the little figures.

In Cologne there has been developed a very unique, local puppet show called the Kölner Hanneschen Theater. The originator was Christoph Winter who invented the characters, established the standing theatre and remained for fifty years its director. Upon his small stage there appeared not only Kasperle, but a whole row of funny folk types, mirroring in their little scenes the bubbling love of living characteristic of the people they represent. The ingenious showman had a saying that whatever type of man one had to deal with, give him the sort of sausage he most enjoys. In accordance with this idea he provided three shows, one for children, which was amusing but harmless, one for the usual adult audience, which was more sophisticated, and one especially suited to the rough Sunday crowd of laboring men who thronged into the show, which, needless to say, was as vulgar as possible. Hanneschen, Mariezebill, Neighbor Tünnes and his wife, the village tailor and a host of others were always introduced and furthermore any person in the vicinity who had made himself unpopular was sure to be caricatured. Neither rank nor age was a protection. Another unvarying principle was the happy ending; even Romeo and Juliet was altered to comply with the rule.

It is difficult now, perhaps, to think of Munich as it was just before the war, a joyous center of literature and art. It was, however, in this happy environment that the puppets rose to the very summit of their honors and successes. In Munich one may find two charming little buildings which were erected and maintained solely for the marionettes. The oldest of these was built for the old showman, fondly called Papa Schmidt by his devoted public. His career was a long one, terminating with gratifying appreciation which many another worthy marionettist has unfortunately failed to receive. It was in 1858 that the actor, Herr Schmidt, took over a complete little puppet outfit of the retired General von Heydeck who had been entertaining King Louis and his court with satirical little puppet parodies. Installing these dolls in a Holzbaracke he opened a permanent theatre there for which Graf Pocci, his constant advisor and friend, wrote the first play based upon the tale of Prinz Rosenrot und Prinzessin Edelweiss. Graf Pocci continued all his life to write little fairy plays for these puppets, over fifty in all. The subjects were well known fairy tales, Undine, Rapunzel, Schneewitschen, Der Rattenfänger von Hamlin, Dornröschen, and all the others. The children loved them and the merry little Kasperle whose humor, if a bit clumsy, was altogether clean and wholesome. Encouraged by his initial success, Schmidt went to great expense and pains to enlarge and elaborate his cast. His daughter, an assiduous helper, was kept busy dressing the dolls of which there were eventually over a thousand.

After long years of success, Papa Schmidt experienced some difficulties due to moving his puppet show and decided to retire. To the honor of Munich be it said, however, that he was not allowed to do so. The city magistrates who, as youngsters, had adored the antics of Kasperle, voted unanimously to build a municipal puppet theatre and to rent it to old Papa Schmidt for his marionette shows. This was done and in a small comfortable building situated in one of the parks, with an adequate auditorium and stage, with space for the seven operators who guide the wires and manage the complicated mechanism for transformations and surprises, with trained readers to speak the parts behind the scenes, with choruses and music whenever they were required, the ninety-four year old showman worked with his dolls until the end of his life, furnishing happy hours to countless children.

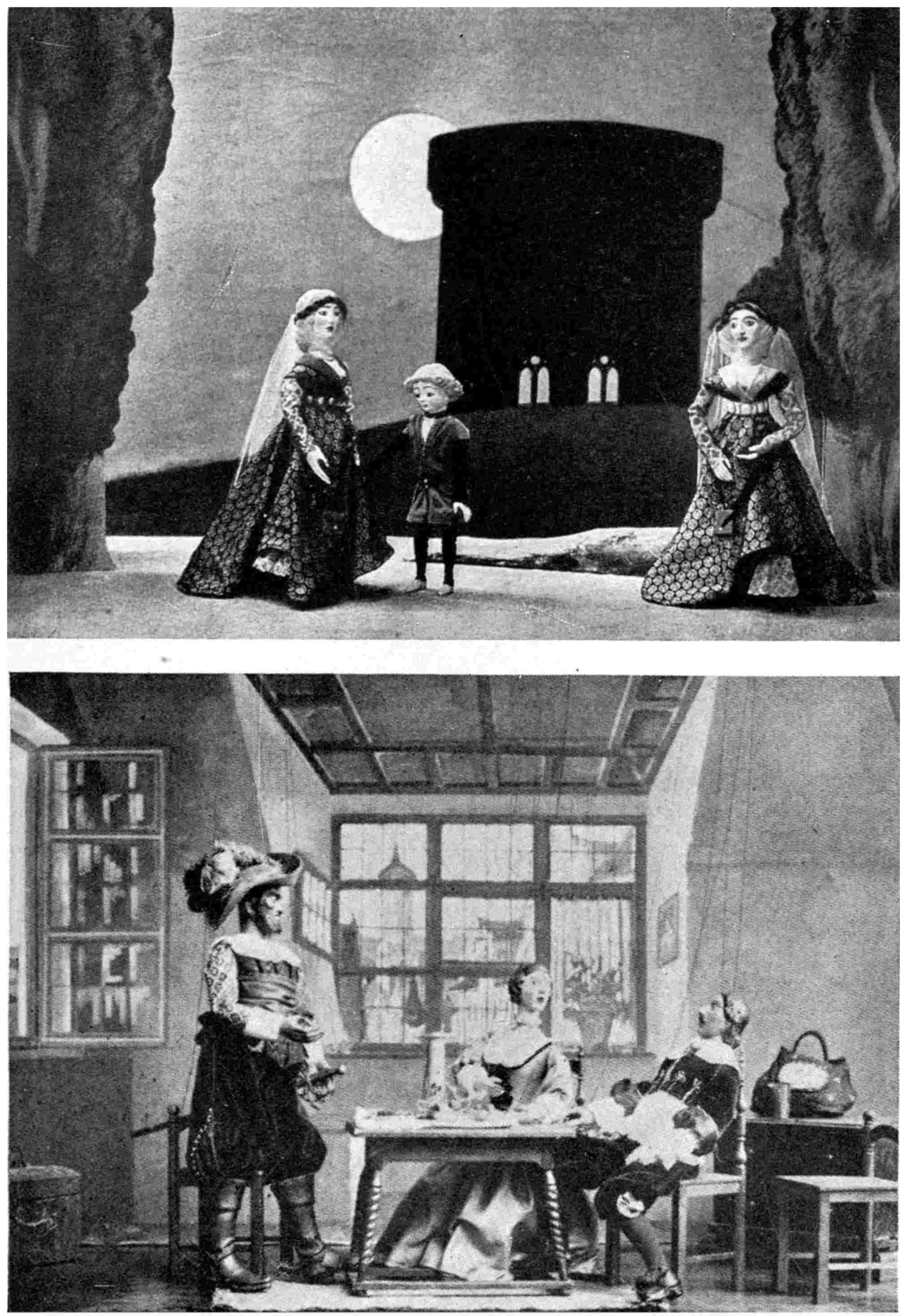

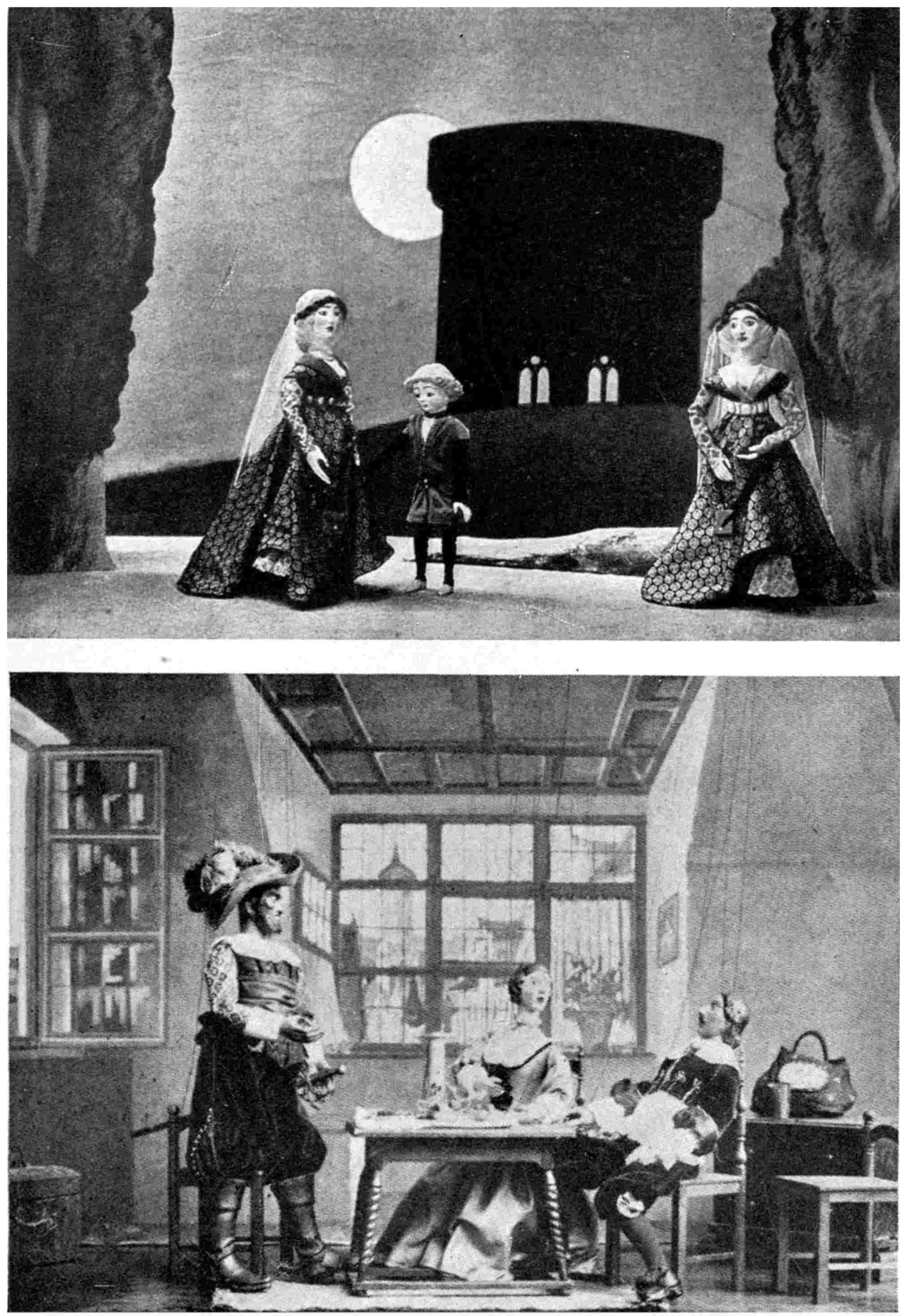

MARIONETTE THEATRE OF MUNICH ARTISTS

Upper: Scene from Maurice Maeterlinck’s The Death of Tintagiles

Lower: Scene from Arthur Schnitzler’s The Gallant Cassian

The celebrated Marionette Theatre of Munich Artists, although inspired by the example of Papa Schmidt, was founded upon an altogether different basis and with other aims and ideals. Paul Brann, an author of local fame, was the instigator of it as well as its director. This small but elaborate modern theatre was built by Paul Ludwig Troost, and decorated elegantly but with careful taste, by other artists interested in the enterprise. The stage itself is equipped with every possible device useful to any modern theatre. There is a revolving stage such as that used by Reinhardt, and a complicated electrical apparatus which can produce the most exquisite lighting effects. The expensive furniture is often a product of the Königlichen Porcellan Manufactur. The mechanism for operating the figures is very perfect, the dolls themselves as well as the costumes, scenery, curtains, programs, etc., are all designed and executed by well known artists such as Joseph Wackerle and Taschner, Jacob Bradle, Wilhelm Schulz, Julius Dietz and many others. Indeed the scenic effects produced at this little marionette theatre have given it the reputation of a model in modern stagecraft.

The triumphs of these Munich puppets, however, do not depend altogether on pictorial successes. Upon the miniature stage there are presented dramas of the best modern poets as well as the older classic plays and the usual Kasperle comedies. Puppets must remain primitive or they lose their own peculiar charm, but the primitive quality may be ennobled. Brann does not in the least detract from the innate simplicity which the marionettes possess. Indeed, he considers this not a limitation but a distinguishing trait. However, he has added poetic art to the old craft and has expanded the sphere of the puppets. He has proven their poetic possibilities and justified their claim to the consideration of cultured audiences. The repertory has been specially selected to suit his particular dolls, somewhat pantomimic, on the whole, with a great deal of music. Generally the plays deal with incidents unrelated to everyday life and these marionettes convey their audiences with unbelievable magic to arcadian lands of dream and wonder. Graf Pocci’s little Kasperle pieces were not scorned by these artistic marionettes nor the old Faustspiel, Don Juan and the Prodigal Son, nor the folk-plays of Hans Sachs. To these were added a rich variety, including many forgotten operettas of Gluck, Adam, Offenbach, Mozart and others, Schnitzler’s Der Brave Cassian, Maeterlinck’s Death of Tintagiles, and Sister Beatrice, and dramas of Hoffmansthal. The popularity of these puppet productions in Munich, and their success all over the world, where they have been taken travelling into foreign lands, attest the worth and value of the interesting experiment. For art, music and literature a new medium has been discovered, or rather an old one re-adapted to suit the requirements of the modern poetic drama.

Of recent years the shadow play has not been altogether overlooked in Munich. In a 1909 issue of the Hyperion, Franz Blei, æsthete and critic, describes two exquisite shadow plays performed in the salon of Victor Mannheimer. The figures and scenery were the work of a young architect, Höne; actors read the text, and Dr. Mannheimer directed. “One thing,” writes Blei, “I believe was clear to all present: that both of the plays thus presented, unhampered by perspiring, laboring and painted living actors, appealed more strongly to the inner ear than they could possibly have done in any other theatre. The author was allowed to express himself, rather than the actor. The stage setting and the outlines of the shadows, very delicately cut in accordance with the essential traits of the characters, presented no more than a delightful resting place for the eye