Puppetry in England

“Triumphant Punch! with joy I follow thee

Through the glad progress of thy wanton course.”

THUS exclaims Lord Byron, and he is but one of the long list of English poets, dramatists and essayists who have found delight and inspiration at the puppet booth. “One could hardly name a single poet from Chaucer to Byron, or a single prose writer from Sir Philip Sidney to Hazlitt in whose works are not to be found abundant information on the subject or frequent allusions to it. The dramatists, above all, beginning with those who are the glory of the reigns of Elizabeth and James I, supply us with the most curious particulars of the repertory, the managers, the stage of the marionettes.” With this introduction M. Magnin brings forward a brilliant array of English authors in whose works we may find traces of the puppets, Shakespeare, Ben Jonson, Beaumont and Fletcher, Milton, Davenant, Swift, Addison, Steele, Gay, Fielding, Goldsmith, Sheridan and innumerable others.

In The Winter’s Tale Autolycus remarks: “I know this man well. He hath been a process server, a bailiff, then he compassed a motion of The Prodigal Son.” Many other dramas of Shakespeare have similar allusions. Milton’s Areopagitica contains these lines: “When God gave Adam reason, he gave him freedom to choose: he had else been a mere artificial Adam, such an Adam as seen in the motions.”

Perhaps the casual mention of a popular diversion in the literature of a nation is not as impressive as the fact that it has served to suggest the themes of numberless dramas and poems. Shakespeare is said to have taken the idea for Julius Cæsar from the puppet play on the same subject which was performed near the Tower of London in his day; Ben Jonson’s Everyman Out of his Humour, Robert Greene’s Orlando Furioso, Dekker’s best drolleries and certainly Patient Grissel in the composition of which he had a hand, Marlowe’s The Massacre at Paris and many others may safely be said to have been suggested by the puppets. There are marionettes in Swift’s A Tale of a Tub, illustrated by Hogarth.

Some authorities claim that Milton drew the argument for his great poem from an Italian marionette production of Paradise Lost which he once witnessed. Byron is supposed to have found the model for his Don Juan in the popular play of Punch’s, The Libertine Destroyed. Hence it cannot be an exaggeration to state that even in England, where the puppets are not supposed to have attained such prestige as on the Continent, they were, nevertheless, not wholly insignificant nor without weight.

As is usually the case, the puppets in England appear to have had a religious origin. Magnin mentions as an undoubted fact the movement of head and eyes on the Crucifix in the monastery of Boxley in Kent, and one hears not only of single articulated images but of passion plays performed by moving figures within the sacred edifices. E. K. Chambers has found the record of a Resurrection Play in the sixteenth century by “certain small puppets, representing the Persons of Christe, the Watchmen, Marie and others.” This was at Whitney in Oxfordshire, “in the days of ceremonial religion,” and one of these puppets which clacked was known as Jack Snacker of Whitney. It is certain that similar motions of sacred dramas and pageants given by mechanical statuettes were not unusual within the Catholic churches, and that during the reign of Henry VIII they were destroyed, as idols. Under Elizabeth and James, religious puppet-shows went wandering about the kingdom, giving the long drawn out moralities and mysteries, The Prodigal Son, The Motion of Babylon and Nineveh with Jonah and the Whale, a great favorite.

These early motions or drolls were a combination of dumb show, masques and even shadow play. Flögel explains that the masques were sometimes connected with the puppets or given sometimes as a separate play. “These masques,” he writes, “consist of five tableaux or motions which take place behind a transparent curtain, just as in Chinese shadows. The showman, a silver-covered wand in his hand and a whistle for signalling, stands in front of the curtain and briefly informs the audience of the action of the piece. Thereupon he draws the curtain, names each personage by name as he appears, points out with his wand the various important actions of his actors’ deeds, and relates the story more in detail than formerly. Another masque which Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair describes is quite different, for here the puppets themselves speak, that is, through a man hidden behind the scenes, who like the one standing out in front is called the interpreter.”

As early as 1575 Italian pupazzi appeared in England and established themselves there. An order of the Lord Mayor of London at the time authorizes that, “Italian marionettes be allowed to settle in the city and to carry on their strange motions as in the past and from time immemorial.” Piccini was a later Italian motion-man, but very famous, giving shows for fifty years and speaking for his Punch to the last with a foreign accent.

There is little doubt, despite much discussion, that the boisterous English Punch is a descendant of the puppet Pulcinello, brought over by travelling Italian showmen. Isaac d’Israeli writes of his ancestry, in the second volume of Curiosities of Literature, “Even Pullicinella, whom we familiarly call Punch, may receive like other personages of not greater importance, all his dignity from antiquity: one of his Roman ancestors having appeared to an antiquary’s visionary eye in a bronze statue: more than one erudite dissertation authenticates the family likeness, the long nose, prominent and hooked; the goggle eyes; the hump at his back and breast; in a word all the character which so strongly marks the Punch race, as distinctly as whole dynasties have been featured by the Austrian lip or the Bourbon nose.”

The origin of the name Punch has given rise to various theories. Some claim it is an anglicizing of Pulcinello, Pulchinello or Punchinello; others that it is derived as is Pulcinello from the Italian word pulcino, little chicken, either, some say, because of the squeak common to Punch and to the chicken or, others aver, because from little chicken might have come the expression for little boy, hence puppet. Again, it is maintained that the origin is the English provincialism punch (short, fat), allied to Bunch.

The older Punchinello was far less restricted in his actions and circumstances than his modern successor. He fought with allegorical figures representing want and weariness, as well as with his wife and the police. He was on intimate terms with the Patriarchs and the champions of Christendom, sat on the lap of the Queen of Sheba, had kings and lords for his associates, and cheated the Inquisition as well as the common hangman. After the revolution of 1688, with the coming of William and Mary, his prestige increased, and Mr. Punch took Mrs. Judy to wife and to them there came a child. The marionettes became more elaborate, were manipulated by wires and developed legs and feet. Queen Mary was often pleased to summon them into her palace. The young gallant, Punch, however, who had been but a garrulous roisterer, causing more noise than harm, began to develop into a merry but thick-skinned fellow, heretical, wicked, always victorious, overcoming Old Vice himself, the horned, tailed demon of the old English moralities. A modified Don Juan, when Don Juan was the vogue, he gradually became a vulgar pugnacious fellow to suit the taste of the lower classes.

During the reign of Queen Anne he was high in popular favor. The Tatler mentions him often, also The Spectator; Addison and Steele have both aided in immortalizing him. Famous showmen such as Mr. Powell included him in every puppet play, for what does an anachronism matter with the marionettes? He walked with King Solomon, entered into the affairs of Doctor Faustus, or the Duke of Lorraine or Saint George in which case he came upon the stage seated on the back of St. George’s dragon to the delight of the spectators. One of his greatest successes was scored in Don Juan or The Libertine Destroyed where he was in his element, and we find him in the drama of Noah, poking his head from behind the side curtain while the floods were pouring down upon the Patriarch and his ark to remark, “Hazy weather, Mr. Noah.” In one of Swift’s satires, the popularity of Punch is declared to be so enormous that the audiences cared little for the plot of the play, merely waiting to greet the entrance of their beloved buffoon with shouts of laughter.

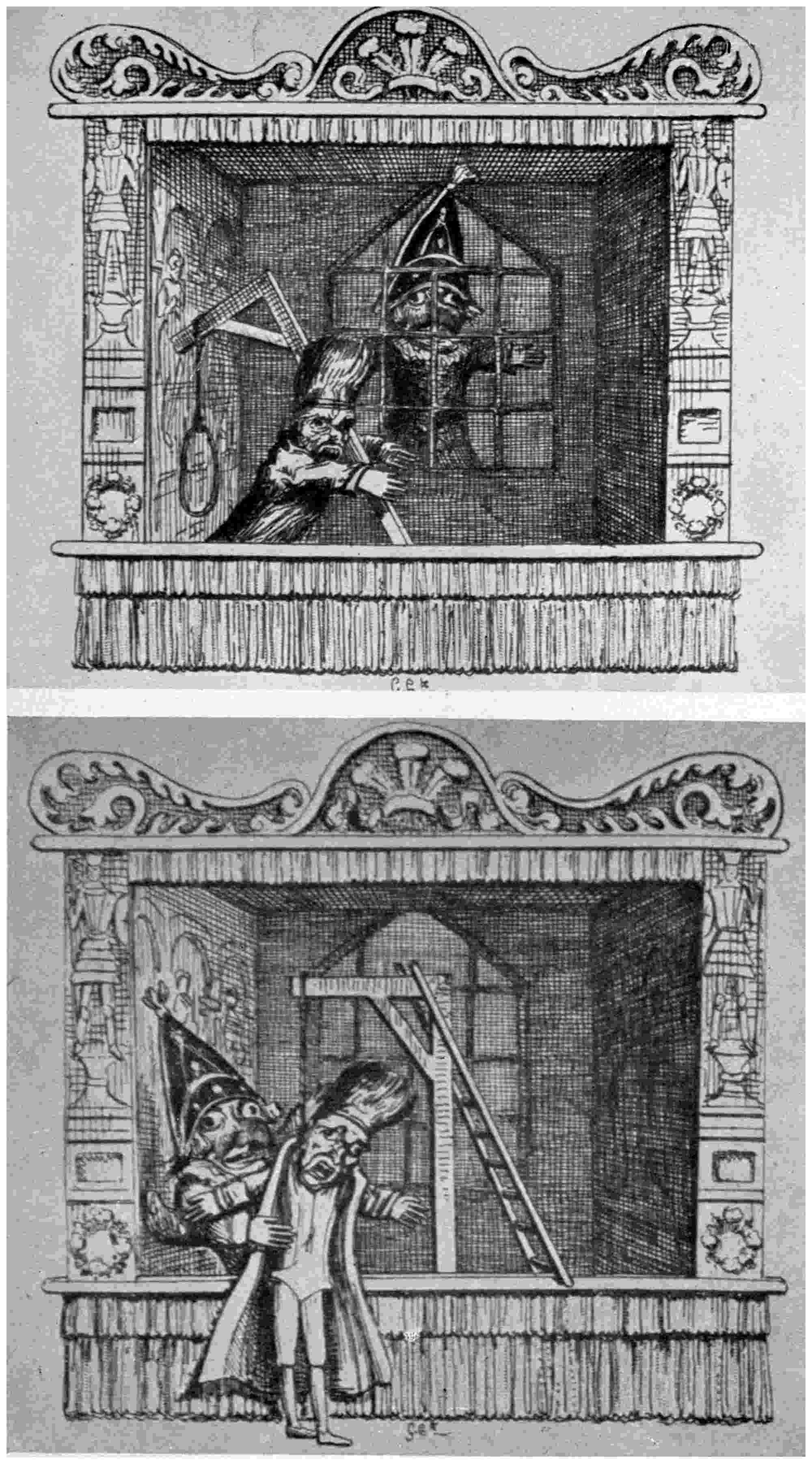

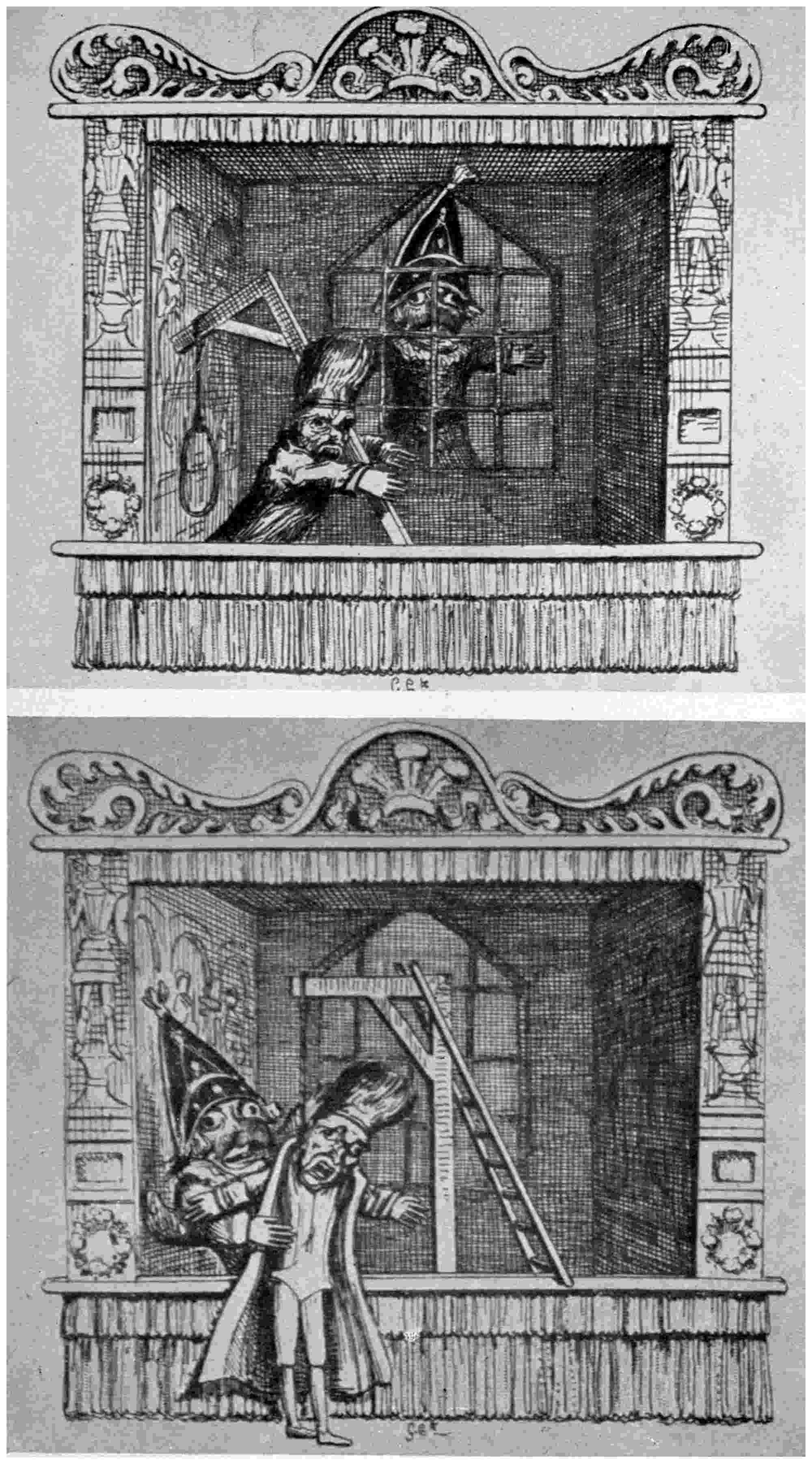

PUNCH HANGS THE HANGMAN

From a Cruikshank illustration of Payne-Collier’s Tragical Comedy of Punch and Judy

At the beginning of the nineteenth century when Lord Nelson, as the hero of Abukir, was represented upon every puppet stage, he and Mr. Punch held the following dialogue:

“Come to my ship, my dear Punch, and help me defeat the French. If you like I will make you a Captain or a Commodore.”

“Never, never,” answered Punch. “I would not dare for I am afraid of being drowned in the deep sea.”

“But don’t have such absurd fears,” replied the Admiral. “Remember that whoever is destined from birth to be hanged will never be drowned.”

Gradually a sort of epic poem of Punch grew up, and there were regular scenes where the dissolute, hardened fellow beats his wife and child, defies morality and religion, knocks down the priest, fights the devil and overcomes him. In 1828 Mr. Payne-Collier arranged a series of little plays called The Tragical Comedy of Punch and Judy. In this labor he was assisted by the records of the Italian, Piccini, who, after long years of wandering through England, had established his Punch and Judy show in London. The series was profusely and delightfully illustrated by Cruikshank. These pictures and those of Hogarth have perpetuated for all times the funny features of Punch and Judy.

“With real conservatism,” writes Maindron, “the English have preserved the figure and repertory of Punch almost as it was in the oldest days of Piccini and his predecessors.” And it is thus one might find Punch on the street corner to-day, maltreating his long-suffering wife, teasing the dog, hanging the hangman. Mr. W. H. Pollock tells us of stopping with Robert Louis Stevenson to watch a Punch and Judy show given by a travelling showman in “bastard English and slang of the road.” Stevenson delighted in it, and Mr. Pollock himself exclaimed: “Everybody who loves good, rattling melodrama with plenty of comic relief must surely love that great performance.”

But to return to the shows and showmen of other times. In the Elizabethan period the motions were very prominent. The puppets sometimes took over plays of the day, and satirized them cleverly upon their own stages, the dolls costumed as nearly as possible like the prominent actors whom they imitated. Later, when for a time the Puritans abolished the theatres, the marionettes were allowed to continue their shows, and thus the entire repertory of the real stage fell into their hands. Permanent puppet stages grew up all over London: people thronged to the puppets.

In Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair he allows the showman, Lanthorn Leatherhead, to describe his fortunes: “Ah,” he said, “I have made lots of money with Sodom and Gomorrah and with the City of Norwich but Gunpowder Plot, that was a veritable gift of God. It was that that made the pennies rain into the coffers. I only charged eighteen or twenty pence per head for admission, but I gave sometimes nine or ten representations a day.” Captain Pod, a seventeenth century showman mentioned in other writings of Ben Jonson, had a large repertory including, among other plays, Man’s Wit, Dialogue of Dives, Prodigal Son, Resurrection of the Saviour, Babylon, Jonah and the Whale, Sodom and Gomorrah, Destruction of Jerusalem, City of Nineveh, Rome and London, Destruction of Norwich, Massacre of Paris with the Death of the Duke de Guise and The Gunpowder Plot. In 1667 Pepys records in his Diary that he found “my Lady Castlemane at a puppet play, Patient Grizell.” The Sorrows of Griselda, indeed, was very popular at the time, also Dick Whittington, The Vagaries of Merry Andrew and The Humours of Bartholomew Fair. The marionettes, indeed, grew so much the vogue, and the rivalry was felt so keenly by the regular theatres, that in 1675 the proprietors of the theatre in Drury Lane and near Lincoln’s Inn Fields formally petitioned that the puppets in close proximity be forbidden to exhibit, or be removed to a greater distance, as they interfered with the success of their performances.

But not alone the theatres objected to the competition of the puppets. One may read in The Spectator, XVI, that young Mr. Powell made his show a veritable thorn in the flesh of the clergy. It was stationed in Covent Garden, opposite the Cathedral of St. Paul, and Powell proceeded to use the church bell as a summons to his performances, luring away worshippers from the very door of the church. Finally the sexton was impelled to remonstrate. “I find my congregation taking the warning of my bell, morning and evening, to go to a puppet show set forth by one Powell, under the Piazzas, etc., etc. I desire you would lay this before the world, that Punchinello may choose an hour less canonical. As things are now, Mr. Powell has a full congregation while we have a very thin house.”

This same Powell was the most successful motion maker of his day. He originated the Universal Deluge in which Noah and his family enter the ark, accompanied by all the animals, two and two. This show was given fifty-two consecutive nights, and was repeated two centuries later by the Prandi brothers in Florence. Powell had booths in London, Bath and Oxford, and played to most fashionable audiences. The Tatler and The Spectator mention him frequently. It was his Punch who sat on the Queen of Sheba’s lap, who danced with Judy on the Ark, and made the famous remark to Noah concerning the weather. He gave numerous religious plays, such as the “Opera of Susannah or Innocence Betrayed,—which will be exhibited next week with a new pair of Elders.” In 1713 he presented Venus and Adonis or The Triumphs of Love, a mock opera. As another attraction to his shows, the ingenious marionettist invented a fashion model, the little puppet, Lady Jane, who made a monthly appearance, bringing the latest styles from Paris. The ladies flocked to the puppets when she was announced on the bills.

A well known competitor of Powell was Pinkethman, in whose scenes the gods of Olympus ascended and descended to strains of music. Crawley was another rival. He advertised his show as follows: “At Crawley’s Booth, over against the Crown Tavern in Smithfield, during the time of Bartholomew Fair, will be presented a little opera called the Old Creation of the World, yet newly revived, with addition of Noah’s Flood, also several fountains, playing water during the time of the play. The last scene does present Noah and his family coming out of the Ark with all the beasts, two and two, and all the fowls of the air seen in a prospect sitting upon trees: likewise over the Ark is seen the sun rising in a glorious manner; moreover a multitude of angels will be seen in a double rank, which presents a double prospect, one for the sun, the other for the palace where will be seen six Angels ringing bells. Likewise Machines descend from above, double and treble, with Dives rising out of Hell and Lazarus seen in Abraham’s bosom, besides several figures dancing jigs, sarabands, and country dances to the admiration of the spectators: with the merry conceits of Squire Punch and Sir John Spendall.”

After these motion makers, came other showmen with many inventions. Colley Cibber wrote dramas for marionettes, and his daughter, the actress, Charlotte Clarke, founded a large puppet theatre. Russell, the old buffoon, is said to have been interested in this project also, but it finally failed. When the Scottish lords and other leaders of the Stuart uprising of 1745 were executed on Tower Hill, the beheading was made a feature by the puppet exhibitions at May Fair and was presented for many years after. Later Clapton’s marionettes offered a play of Grace Darling rescuing the crew of the Forfarshire, “with many ingenious moving figures of quadrupeds.” Boswell tells us in his Life of Johnson about Oliver Goldsmith, who was so vain he could not endure to have anyone do anything better than himself. “Once at an exhibition of the fantoccini in London, when those who sat next to him observed with what dexterity a puppet was made to toss a pike, he could not bear that it should have such praise, and exclaimed with some warmth, ‘Pshaw! I could do it better myself!’” Boswell adds in a note, “He went home with Mr. Burke to supper and broke his shin by attempting to exhibit to the company how much better he could jump over a stick than the puppets.” Dr. Johnson was a great admirer of the fantoccini in London, and considered a performance of Macbeth by puppets as satisfactory as when played by human actors.

At the end of the eighteenth century, Flockton’s show displayed five hundred figures at work in various trades. Browne’s Theatre of Arts, 1830–1840 travelled about at country fairs showing The Battle of Trafalgar, Napoleon’s Army Crossing the Alps and the Marble Palace of St. Petersburg. Some marionettes of the nineteenth century became satirical, attacking literature and politics with mischievous energy. Punch assumed a thousand disguises; he caricatured Sheridan, Fox, Lord Nelson. William Hazlitt wrote seriously in praise of puppet shows.

There are gaps in the history of English puppets which seem to imply a decline in the popularity of that amusement. One comes upon occasional records of shows straggling through the countryside, and giving the old, timeworn productions of Prodigal Son or Noah, or Pull Devil, Pull Baker. During the reign of George IV, puppets were found at street corners, dancing sailors, milkmaids, clowns, but Punch, as ever, the favorite.

Even now, puppets on boards may be seen in the streets of London. Of the old shows, one resident of that city relates: “When I was a child, marionettes used to go about the streets of London in a theatre on wheels about as big as a barrel organ, but I dare say I am wrong about size, because one cannot remember these things. I remember particularly a skeleton which danced and came to pieces so that his bones lay about in a heap. When I was properly surprised at this he assembled himself and danced again. I was so young that I was rather frightened.”

There is to-day one of the old professional marionette showmen wandering about in England, Clunn Lewiss, who still has a set of genuine old dolls, bought up from a predecessor’s outfit. For fifty years he has been traveling along the roads, like a character strayed out of Dickens. He has interested members of artistic coteries in London, who have been moved by the old man’s appeals for help, and some attempts have been made to revive interest in his show. Surely Clunn Lewiss deserves some recognition.

Altogether unconnected with popular puppets were the highly complicated mechanical exhibitions of Holden’s marionettes. The amazing feats performed by Holden’s puppets astonished not only England, but all the large Continental and American cities where they were displayed. They were tremendously admired. The surprising dexterity of manipulation, and the elegance of the settings had never been surpassed. In Paris, however, de Goncourt wrote of them: “The marionettes of Holden! These creatures of wood are a little disquieting. There is a dancer turning on the tips of her toes in the moonlight that might be a character of Hoffman, etc.

“Holden was more of an illusionist than a true marionettist. He produced exact illusions of living beings, but he was lacking in imagination. The fantoches of Holden were certainly marvels of precision, but they appeal to the eye and not to the spirit. One admired, one did not laugh at them. They astonished, but they did not charm.”

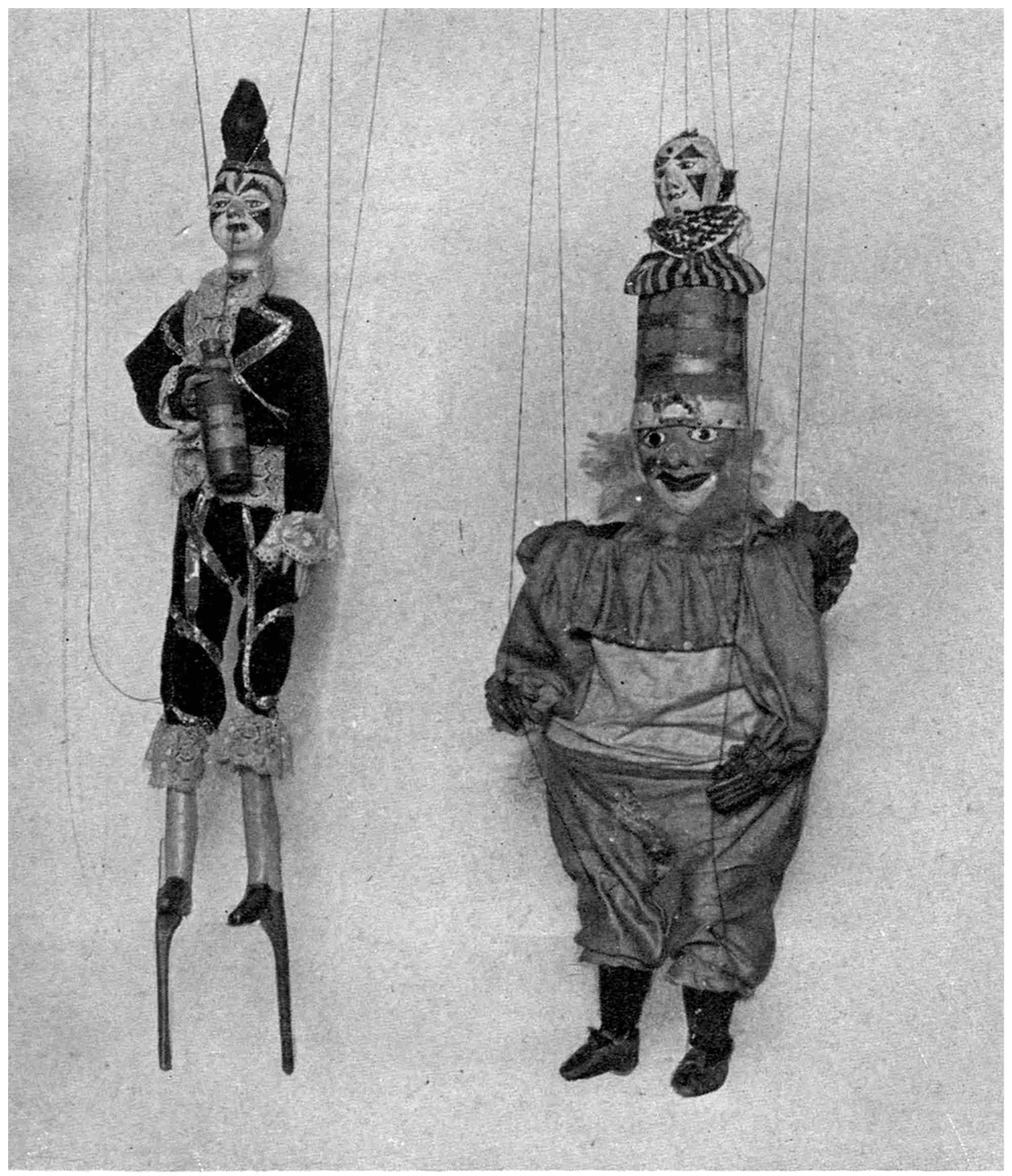

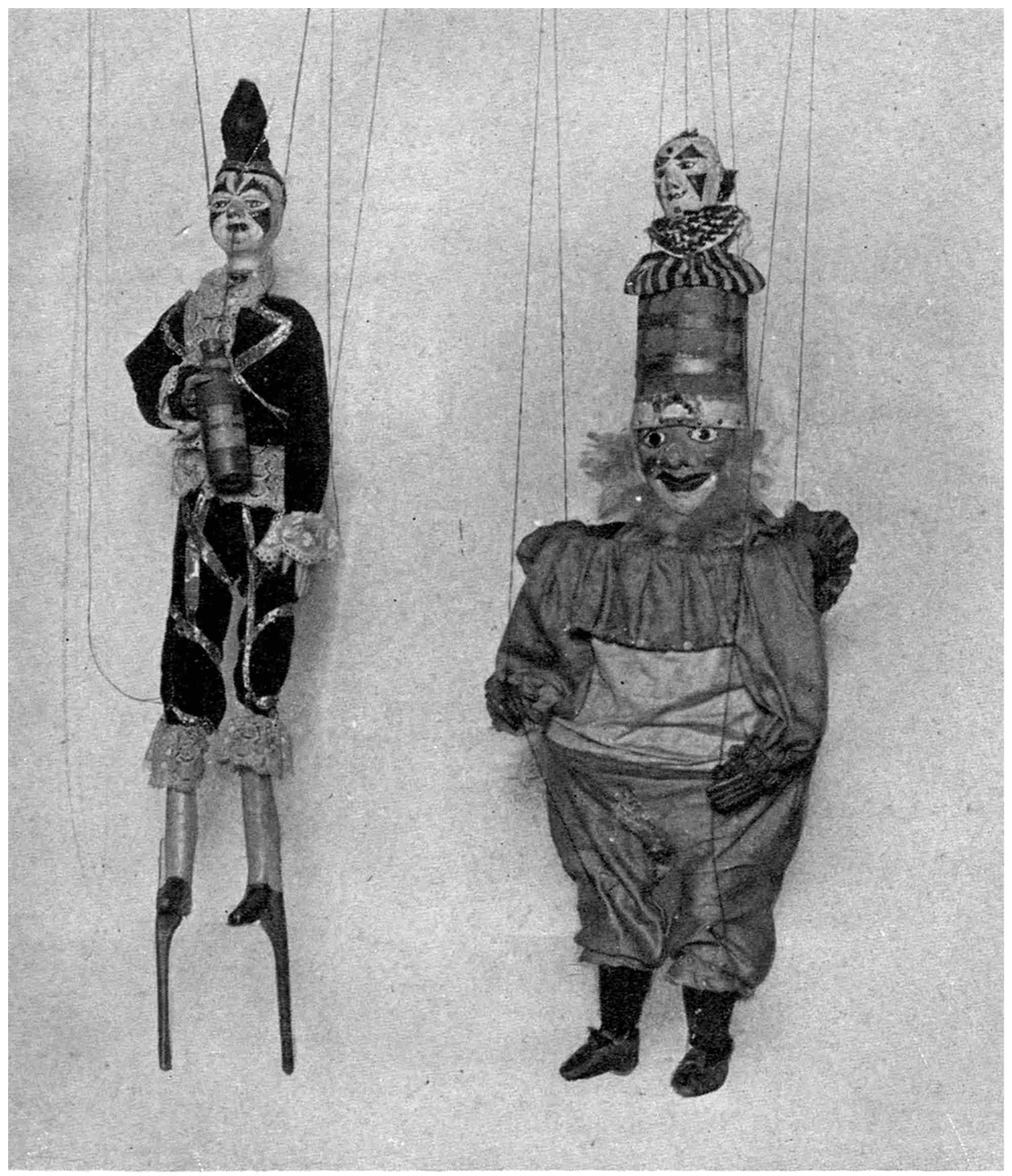

OLD ENGLISH PUPPETS

Used by Mr. Clunn Lewiss in his wandering show

[Courtesy of Mr. Tony Sarg]

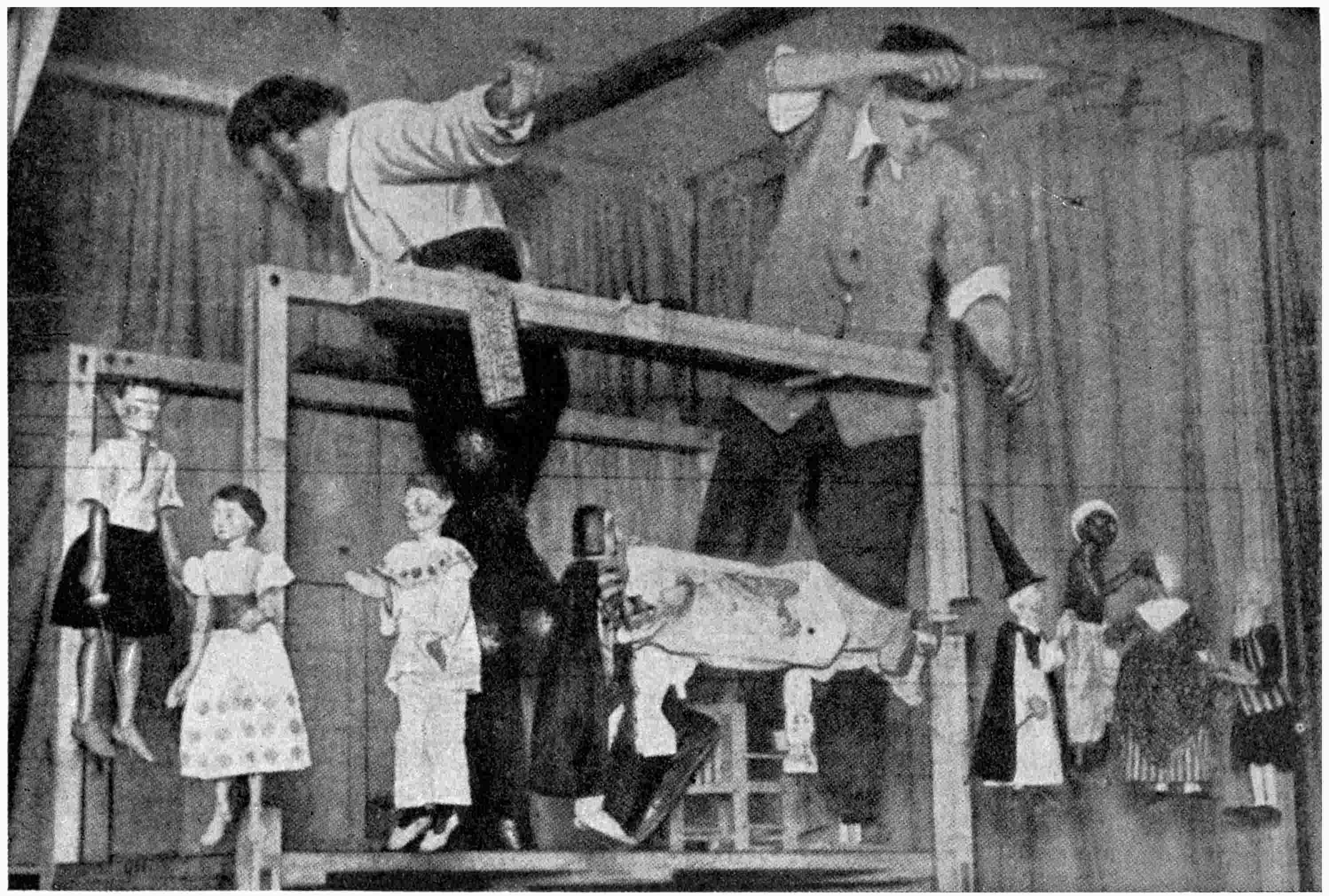

There have been several interesting amateur marionette shows within the last decade. There are the Wilkinsons, two clever modern painters who have taken their puppets from village to village in England and also in France. They traveled about with their family in a caravan and wherever they wished to give a show, they halted and drew forth a stage from the rear end of the wagon. Their dolls are eight inches high or more and they require four operators. They are designed with a touch of caricature, and they perform little plays and scenes invented by the Wilkinsons, very amusing and witty. Not long ago Mr. Gair Wilkinson gave a very successful exhibition of his show at the Margaret Morris Theater in Chelsea for a short season.

The Ilkely Players, of Ilkely, Yorkshire, are a group of young women who produced puppet plays for some five or six years, touring through England. Their dolls were rather simple, mechanically; only the arms were articulated, for the most part; the heads were porcelain dolls’ heads. Nevertheless this group of puppeteers deserves the credit they attained by reviving the classic old show of Doctor Faustus, at Clifford’s Inn Hall, Chelsea. They also gave very interesting productions of Maeterlinck’s The Seven Princesses, and Thackeray’s The Rose and the Ring, dramatized by Miss Dora Nussey, who was the leader of the group. Inspired by their success, Miss Margaret Bulley of Liverpool produced a puppet play of Faustus before the Sandon Studio Club. Miss Bulley’s puppets were quite simple wooden dolls with papier-maché heads and tin arms and legs, each worked with seven black threads. The costumes were copied after old German engravings of the eighteenth century and the production proved very effective.

Most highly perfected, and most exquisite of English puppets to-day are those of the artist, Mr. William Simmonds, in Hampstead. They originated in a village in Wiltshire as an amusement at a Christmas party given by Mr. and Mrs. Simmonds every year to the village children. The audience was so delighted that the next year more puppets were made with a more attractive setting. Friends then became so enthusiastic that the creators of the puppets realized what might be done, and in London, the following Spring, they began giving small private shows.

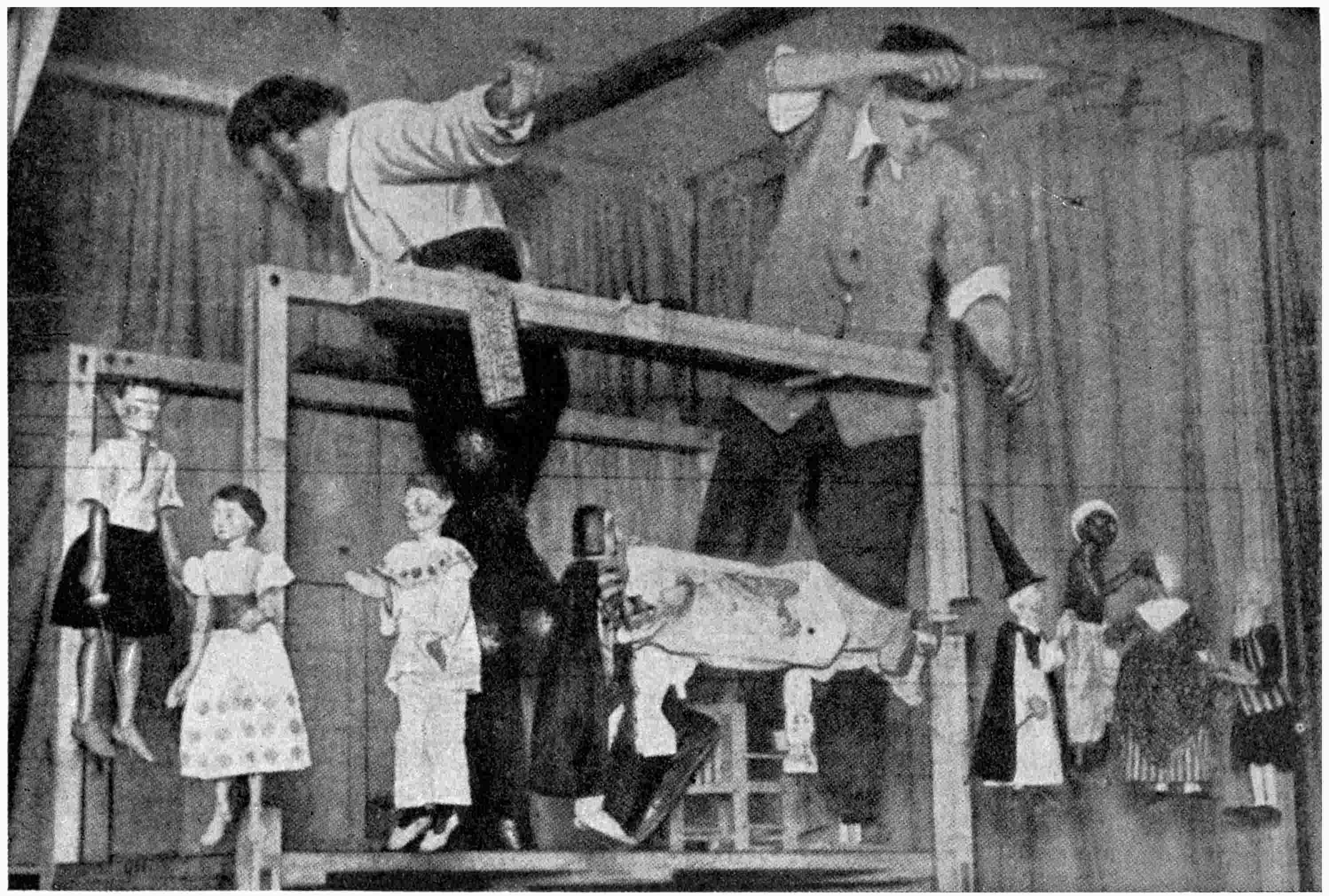

MR. GAIR WILKINSON AND ASSISTANT AT WORK ON THE BRIDGE OF THEIR PUPPET THEATRE [REPRODUCED FROM THE SKETCH, 1916]

The productions are only suited to a small audience of forty or fifty. The puppets are mostly fifteen inches high, some smaller; the stage is nine feet wide, six deep, and a little over two feet high. The scenery is painted on small screens. At present there are three scenes, a Harlequinade, a Woodland Scene and a little Seaport Town. The puppets are grouped to use one or the other of these scenes. They do not do plays but seem to find their best expression in songs and dances connected with various by-play and “business” and a slight thread of episode which is often varied, never twice alike. Mr. Simmonds manipulates the puppets entirely alone and cannot work with anyone close. He frequently operates a puppet in each hand, all with the utmost dexterity and delicacy, and manages others by means of hanging them up and moving them slightly at intervals, at the same time singing, whistling, improvising dialogue or imitating various noises! People generally expect to find half a dozen manipulators behind the scenes.

Mr. Simmonds himself carves the heads, hands and feet of his marionettes in wood (usually lime) and paints them in tempera to avoid shine. They are beautifully done. Some are dressed, some have clothes painted on them. Some are quite decorative, others impressionistic or frankly realistic. Not contented with the little-bit-clumsy doll, Mr. Simmonds has perfected his puppets with great technical skill until they move with perfect naturalness, some with dignity, some with grace, some with humor, each according to its nature.

In the Harliquinade the scene is hung with black velvet, lighted from the front, which gives the effect of a black void against which the figures of Harlequin, Columbine, Clown, Pantaloon and others appear with sparkling brilliancy and vivid color. In the Seaport Town, a medley of characters appear,—a sailor, a grenadier, a fat woman, an old man, the minister, etc. There are songs used in this to give variety. Particularly clever is an English sailor of the time of Nelson who comes out of a public house and dances a jig, heel-tapping the floor in perfect time, his hands on his hips and his body rollicking in perfect character while he sings, “On Friday morn when we set sail.” Another excellent dancing doll is the washerwoman of the old sort, short and stout and great-armed, jolly and roughfaced.

In the Woodland Scene, creatures of the wood appear,—faun, dryad, nymph, young centaurs, baby faun, hunted stag, a forester, a dainty shepherd and a shepherdess, etc. The little sketch is entirely wordless, having only musical accompaniment played by Mrs. Simmonds upon a virginal or a spinet, or an early Erard piano (date 1804). The sound is just right in scale for the puppets; anything else would seem heavy. The fauns in this scene are most popular, particularly the Baby who has an extraordinary tenderness, and skips and leaps with the agility of a live thing. The act of extreme dreaminess and beauty is described thus by one who was privileged to witness it. “In one scene a man went out hunting. He hid behind a bush. A stag came on. He shot the stag which lay down and died. Then there came one or two creatures of the wood, who could do nothing, and at last a very beautiful nymph, lightly clothed in leaves. She succeeded in resuscitating the stag, who got up and bounded away. When they had gone, the hunter who had watched it all from behind the bush came out, and that was all. Music all the time. No words. The stag was quite astonishing.”

Although he is now living and working in Florence, Mr. Gordon Craig must not be omitted from any account of English marionettes and advocates of the puppets. Quite apart from the class of artistic amateurs and equally remote from the usual professional marionettist of to-day, Mr. Craig stands rather as a new prophet of puppetry, recalling in stirring terms the virtues of the old art, and adding his new and individual interpretation of its value.

Puppets are but a small portion of the dramatic experiment and propaganda which Mr. Craig is so courageously carrying on in Florence. But they are not the least interesting branch of his undertakings. He has assembled a veritable museum of marionette and shadow play material from all over the world. Pictures of some parts of his collection appear regularly in “The Marionette.” There are also delightful puppet plays appearing in this pamphlet. But this is not all.

With the marionette used as a sort of symbol, Mr. Craig has been conducting research into the very heart of dramatic verities, and producing dramatic formulas which should apply on any stage at any time. He has invented his marionettes to express dramatic qualities which he deems significant, and in his puppets he has attempted to eliminate all other disturbing and unnecessary qualities. Thus he creates little wooden patterns or models for his artists of the stage, and he applies in actual usage Goethe’s maxim: “He who would work for the stage ... should leave nature in her proper place and take careful heed not to have recourse to anything but what may be performed by children with puppets upon boards and laths, together with sheets of cardboard and linen.”

At the beginning of his experiments with marionettes Mr. Craig and his assistants constructed one large and extremely complicated doll which was moved on grooves and manipulated by pedals from below, with a small telltale to indicate to the operator the exact effect produced. But this marionette was not satisfactory for Mr. Craig’s purposes.

He then directed his energies in an exactly opposite direction, toward simplification. The result was small, but very impressive dolls, carved out of wood and painted in neutral colors,—the color of the scenes in which they moved, to allow for the fullest and most variable effects produced by lighting. Most interesting, too, the manner in which Mr. Craig applied his theories concerning gesture with these little puppets. Each marionette w