CHAPTER IX

TICKS

A waterleche or a tyke hath neuer ynow, tyl it brestyth.

(Jacob’s Well, 1440.)

TICKS are mites ‘writ large,’ and until about the beginning of this century they were regarded with what one might call mild disgust and regret. Now, however, that they have been proved to play a part—and a very important part—in the dissemination of disease, we have come to regard them, as Calverley said we should regard the Decalogue, ‘with feelings of reverence mingled with awe.’

The body of a tick is covered with a tough, smooth or crinkled skin, capable almost of any amount of extension. Until they have fed they are flattened in shape, but after a meal of blood they very soon lose the outlines of a Don Quixote and attain those of a Sancho Panza. In the adult, the legs are eight in number and have six joints ending in two claws and sometimes in suckers. Some have eyes and some have no eyes.

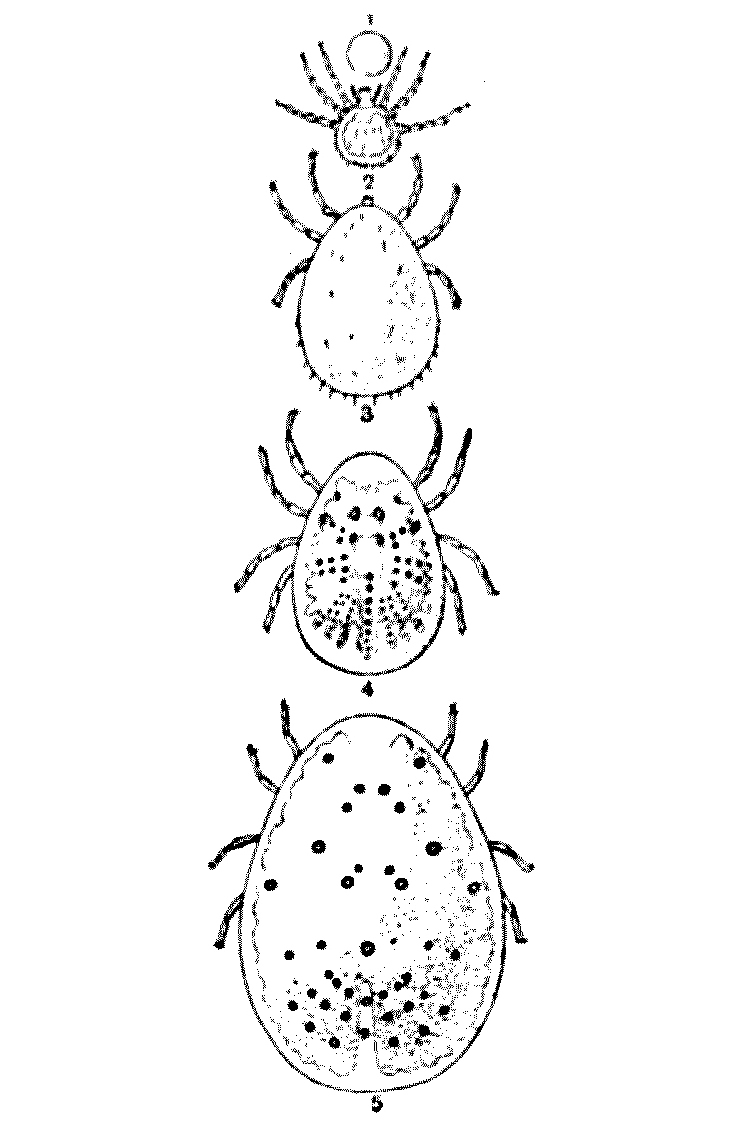

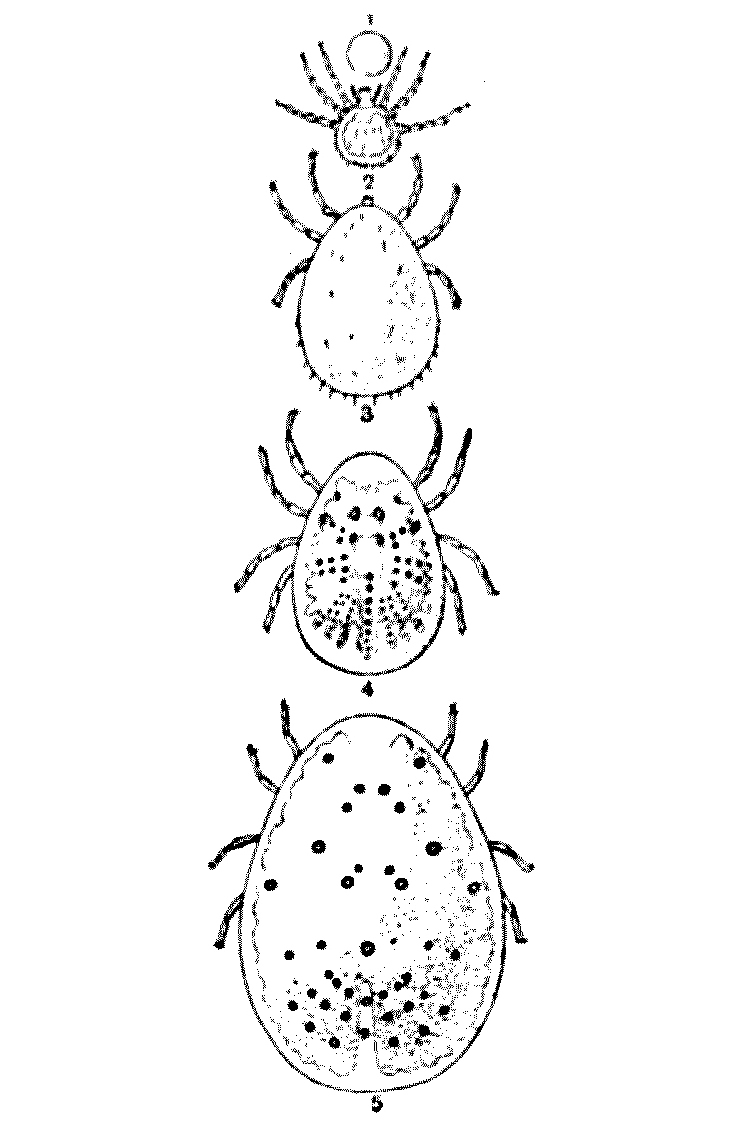

FIG. 41.—Evolution of Argas persicus. 1, the egg; 2, the six-legged larva; 3, the same gorged; 4, an unfed nymph; 5, nymph gorged. (After Brumpt.)

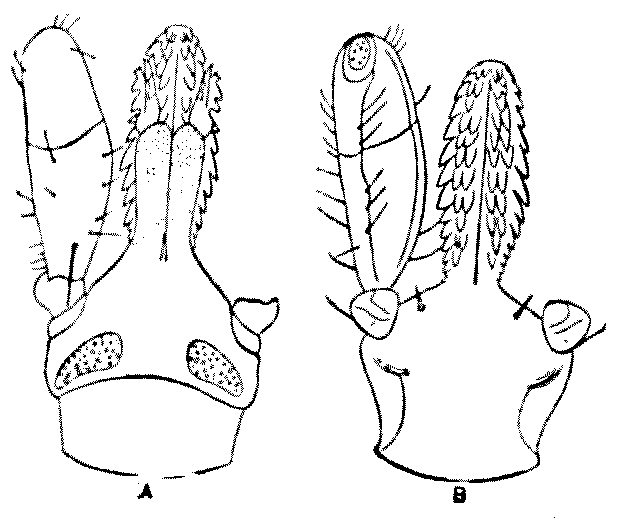

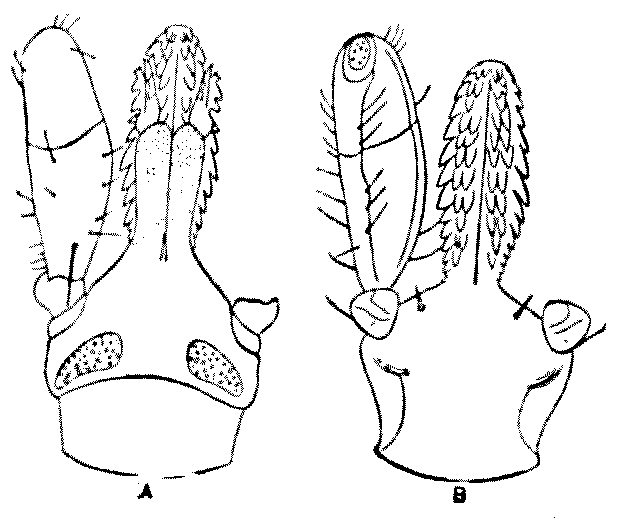

The most formidable part of their armour is, however, the mouth-parts, consisting of the tactile pedipalps, and the piercing-probe which they stick into our bodies. This probe consists of a dorsal membranous sheath and a ventral hypostome armed with recurved teeth, forming together a tube within which play two cutting and tearing chelicerae. When these have cut a way into the flesh they are withdrawn, and the tube is inserted into the wound and blood is pumped up it by the sucking-pharynx. It is the teeth on the hypostome, and not the chelicerae, which anchor the ticks to their prey.

Ticks, as they affect the soldier, may be divided into two families. The first of these, the Argasidae, are usually associated with human dwellings, fowl-houses, dove-cotes, and so on, and are more commonly parasitic on fowls than on cattle or human beings. The members of this group hide away in crevices and corners during the day, and come out at night to feed, for ‘their deeds are evil.’

FIG. 42.—Ixodes ricinus. Mouth-parts of the female: A, seen from the dorsal, B, from the ventral surface. The median, dotted, portion of the left-hand figure is the sheath; the toothed portion the hypostome. The lateral process is the pedipalp shown only on one side. × 35. (After Nuttall and Warburton.)

Argas persicus, known to travellers as the ‘teigne de miana,’ is of an oval form, of brownish-red colour. The male measures 4 mm. to 5 mm. in length by 3 mm. in breadth; the female 7 mm. to 10 mm. in length by 5 mm. to 6 mm. in breadth. This creature frequents the northern parts of Persia, and occurs in many other warm countries. In South Africa it is known as the ‘tampan’ and ‘wandlius,’ where it is mainly a fowl-parasite. In Persia it is very much dreaded, though probably the effects of its bite are due to the unsuitable treatment the punctured skin receives and the consequent invasion of the tissues by septic bacteria. In South Africa it is frequently fatal to fowls, especially to chickens; but the death is there believed to be due to the loss of blood. It is definitely proved to convey Spirochaetosis.

We have not yet explained that ticks pass through several stages as they advance from the egg to the adult. The larval stage of A. persicus will remain on its host for five days. It then leaves, and moults in retirement. After the moulting it visits its host by night and remains on it for about an hour. This second stage, known as the ‘nymph’ stage, moults twice, and the female in each stage becomes much distended with blood—‘gorged,’ as the saying is. With each moult it becomes larger, but otherwise does not alter much in appearance. The adult female also, like the nymph, visits the host from time to time, and between these visits deposits eggs in great quantities in sheltered crevices—some 50 to 100 being deposited at once.

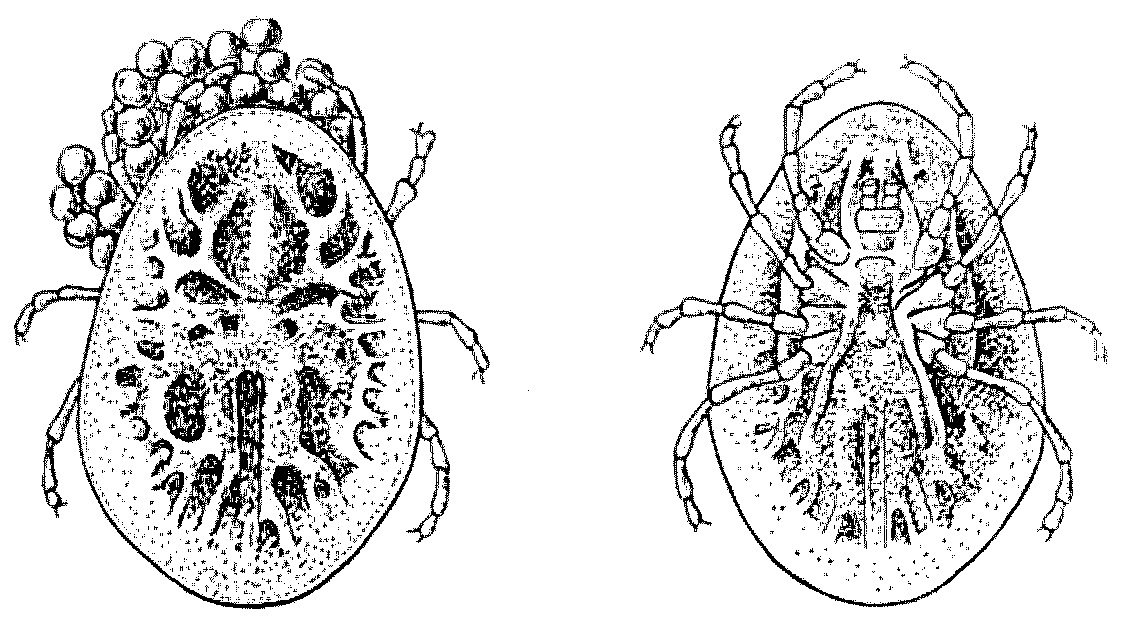

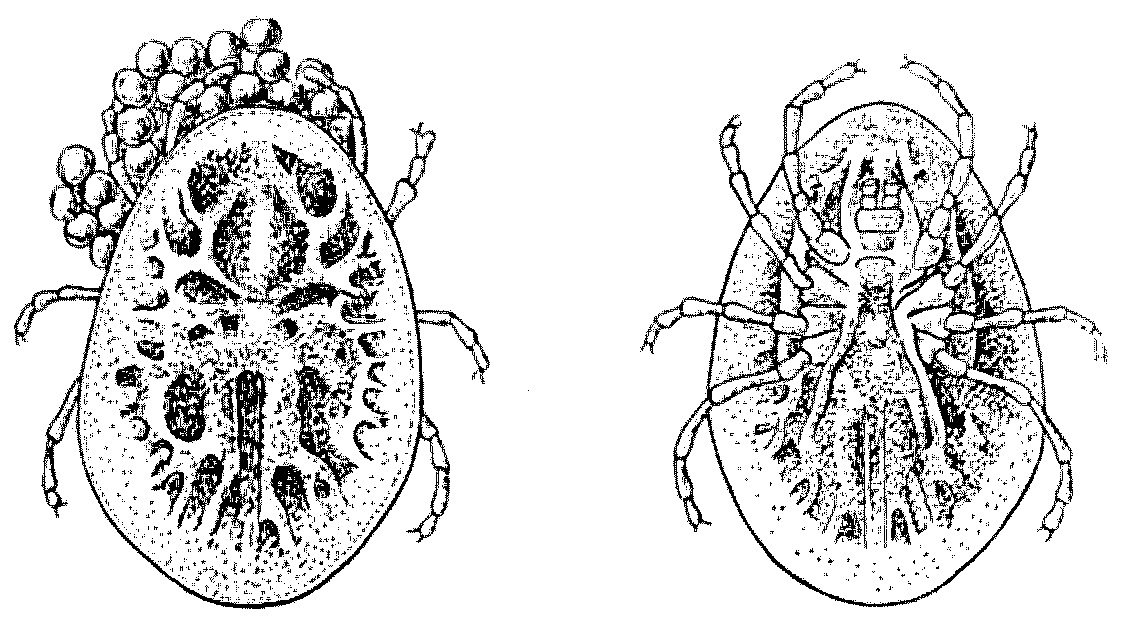

FIG. 43.—Argas reflexus, female. On the left the dorsal view of a specimen laying eggs; on the right a ventral view of the same. (After Brumpt.)

Argas reflexus, the ‘marginated tick,’ is yellow and white—the Papal colours. It is common near dove-cotes and pigeon-houses, and often attacks people sleeping in their neighbourhood. Its bite causes much irritation, and sometimes leads to vesicles and ulcers. At one time it was very common in Canterbury Cathedral, and so worried the worshippers that it took all the eloquence of the ‘Very Reverend the Dean’ to overcome its repellent powers.

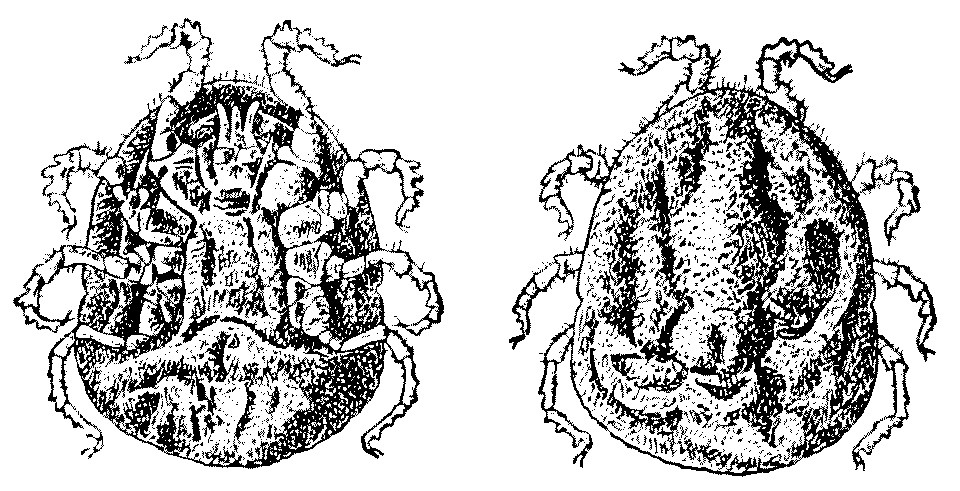

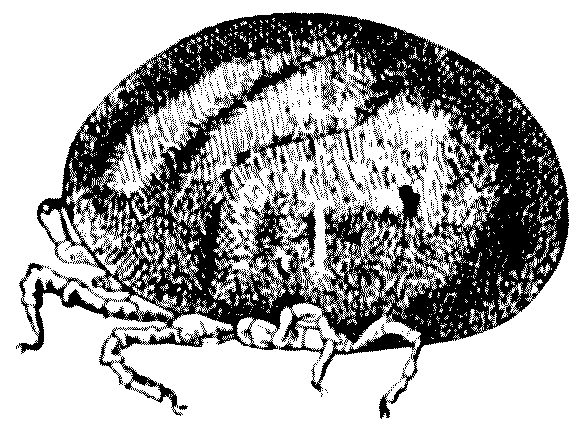

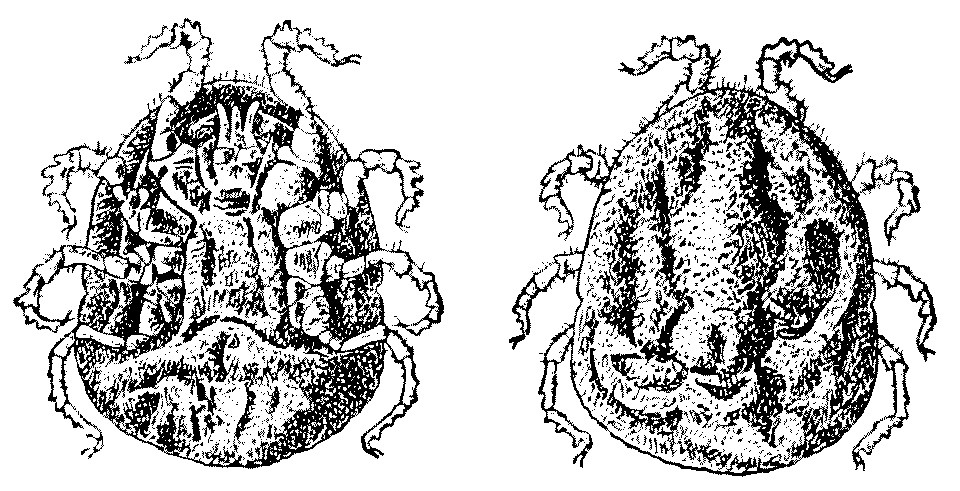

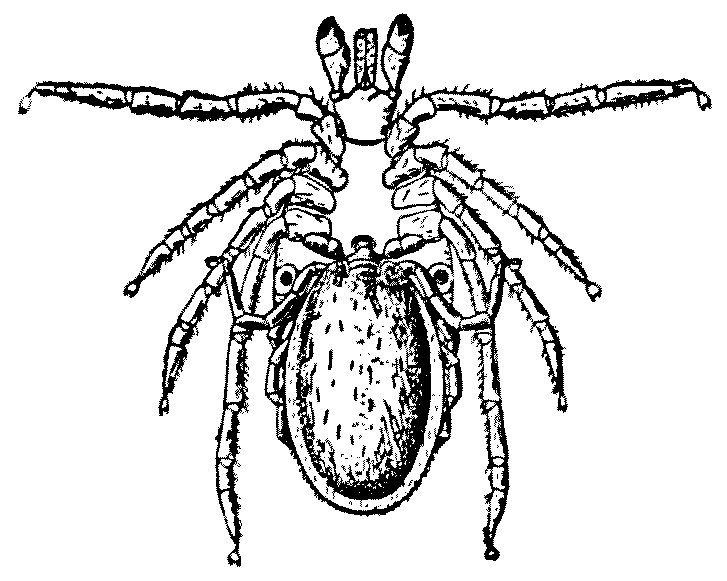

FIG. 44.—Ornithodorus moubata, an unfed female. To the left a ventral, to the right a dorsal view, showing the crinkled skin. (After Brumpt.)

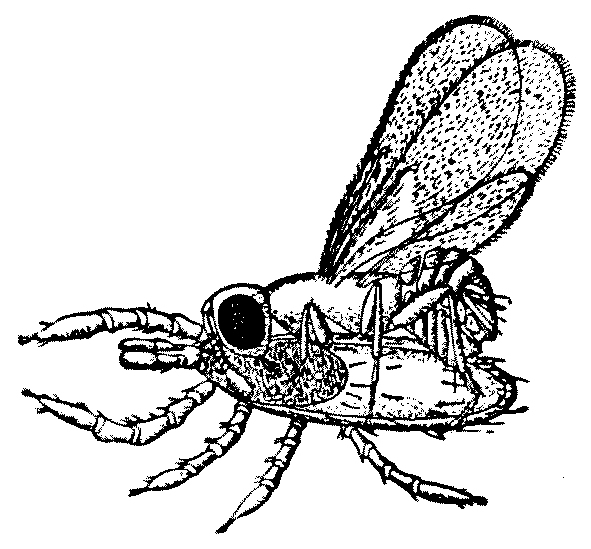

Ornithodorus moubata, sometimes known as the ‘tampan,’ occurs pretty often in South Africa, and was a cause of considerable trouble to our troops during the South African War. It lives normally in the shade of vegetation, but frequently invades the native huts. It is catholic in its taste and attacks most mammals, and it has a decided preference for men. In Uganda the natives frequently die from its bites—dying of so-called ‘tick-fever.’

FIG. 45.—Ornithodorus moubata. Female, gorged, seen in profile. (After Brumpt.)

I myself once assisted in identifying two ticks, in the nymph stage, taken in Cambridge from the ear of an American visitor to this country, who had been camping out in Arizona shortly before his arrival. This tick turned out to be a species of Ornithodorus megnini, which, as a rule, attacks the horse, the ass, and the ox about the ears. But it frequently attacks man, and is well known in the United States, infesting the ears of children. An allied species, O. turicata, proves fatal to fowls in the Southern States and in Mexico, and is very harmful to human beings. The chief harm that these ticks do is to transmit protozoal diseases to man and other animals.

A very few ticks are said to be parthenogenetic, but by far the greater part lay fertilised eggs, and lay them in considerable numbers; and the eggs are agglutinated together in solid little masses, by the sticky secretion of a cephalic gland, which opens below the rostrum. The eggs are small and elliptical, and are laid to the number of many thousands. The young tick, which is usually born with but three pairs of legs, hatches out in a few days if the weather be warm, or a few weeks should it prove cold. A certain amount of moisture must be present, or the eggs are apt to dry up. These masses of eggs are laid on the ground under herbs or grass, or on leaves.

FIG. 46.—Ixodes ricinus. The male is inserting its rostrum in the female genital duct before depositing its spermatophore. × 6. (From Brumpt.)

The issuing six-legged larvae, like the young of other animals, are very agile, climbing on to leaves and herbage. They passionately wait with their front legs eagerly stretching out for the passage of the host upon which they desire to settle. Of course, but one in ten thousand succeeds, and it is terrible to think of the amount of unsatisfied desire which must be going on in the tick world! The rest perish miserably. Those that do succeed attach themselves to the skin of the host, and thrust their rostrum and sucking-tube into the hole already prepared by the cutting chelicerae. They suck the blood, and when gorged fall to the earth, or in some cases remain on the host in a state of inertia or apparent syncope.

Soon, however, the gorged larva moults, and gives rise to the first nymph—an eight-legged creature. This affixes itself anew upon a host—either upon the same or another one—again gorges itself, and in all points resembles the adult, except from the fact that the sexual orifice has not yet appeared. After some days the first nymph moults, and then again remains either on the host or it falls to the ground. In some cases there are two successive nymph forms; but as a rule the first nymph gives rise by a second moult to the adult form, which again for the third time regains a host. The adults are now ripe for pairing, and the male having enlarged the orifice of the oviduct by inserting its rostrum, deposits therein a spermatophore or capsule full of spermatozoa. The female is often successively fertilised by several males.

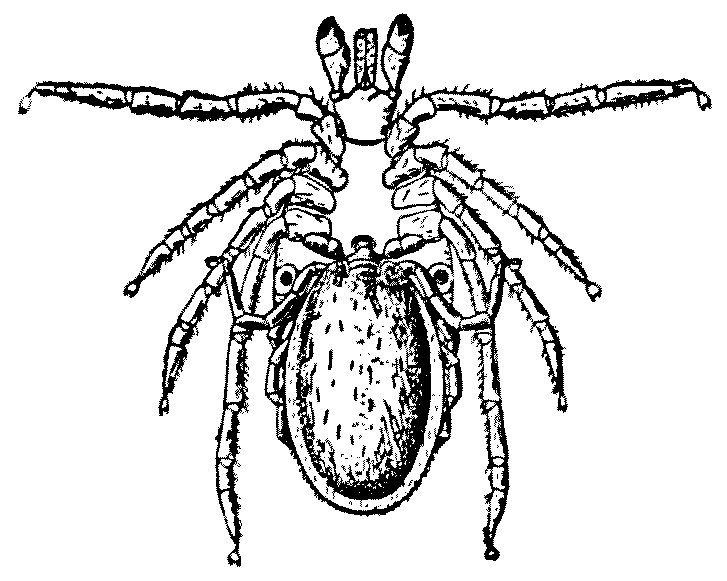

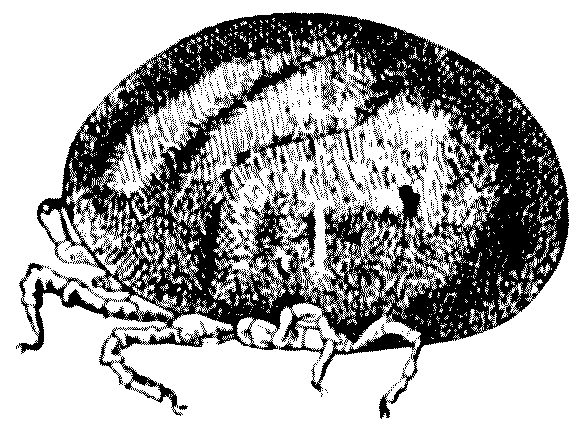

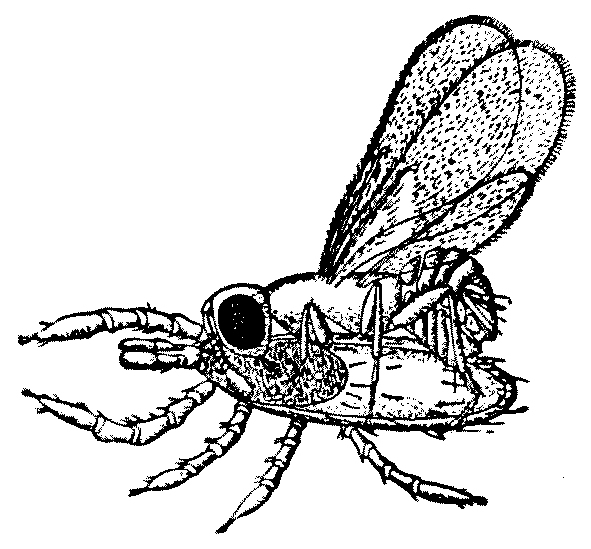

In many cases the male dies after fertilisation. The female swells enormously when gorged, sometimes becoming as large as a filbert, or even a small walnut. These ticks are seldom parasites of one particular host, but attack many mammals indifferently. They have many natural enemies: amongst the most important of which are certain hemipterous insects whose female attacks the nymph of the Ixodes, and lays within the body of the tick a number of eggs which develop inside the nymph until they reach the adult stage, when they make their escape through an orifice, generally at the hind end, leaving behind them the dead body of their host. Three species of such Hemipterous insects are known to be parasitic on ticks: of these Ixodiphagus caucurtei is ubiquitous. It attacks all kinds of ticks, but especially Dermacentor venustus.

FIG. 47.—Ixodiphagus caucurtei laying eggs in the nymph of Ixodes ricinus. × 20. (After Brumpt.)

Ixodes ricinus, of a brownish colour in the male, is very common in England and, indeed, almost everywhere. The female is yellow and flattened, somewhat resembling a grain of rice. It is the well-known dog-tick, but it attacks oxen, goats, deer, horses, and man. It also attacks the grouse, and is particularly common in some parts of Great Britain. It is impossible to rid certain areas of these troublesome guests. In some cases they produce tumours and introduce bacteria, and in cattle it introduces an organism known as Babesia bovis, which is the cause of haematuria in oxen. Dermacentor venustus transmits Rocky Mountain fever, which is common in certain parts of the States. The fever is accompanied with pains in the joints and in the muscles and an eruption on the surface of the skin, appearing first on the wrists and forehead, and invading in time all parts of the body, followed by a scaling of the skin during a period of convalescence. In Montana the mortality caused by this disease is very high, varying in different years from 33 to 75 per cent. In Idaho the mortality is far less, only about 4 per cent.

Ornithodorus moubata inoculates man with a spirochaete (Spirochaeta duttoni), which is the agent of the African tick-fever or relapsing fever. One of the curiosities about the organisms transmitted by ticks is that they live through the whole cycle of the tick’s life. If they are taken in by the larva they are only transmissible by the following larval stage. If they are taken in by the nymph they are only transmissible when again the nymph stage is met with, and the same is true of the adult. Think what such a protozoon must have seen! The fertilisation of the egg by the spermatozoon, the fusion of their nuclei, the extrusion of the polar-bodies, the breaking up of the egg into segments, the gradual building up of the tissues of the larva, the sudden inrush of the host’s blood when the larva is safely fixed, the moulting, the changes in the nymph, the development of the generative organs, the formation of the eggs! What a text-book of embryology and anatomy it could write if only it had descriptive powers! If I may paraphrase Kipling:—

Think where ’e’s been,

Think what ’e’s seen,

Think of his future,

AND GAWD SAVE THE QUEEN!