CHAPTER X

LEECHES

PART I

THE MEDICINAL LEECH (Hirudo medicinalis)

Hardly anything real in the shop but the leeches and they’re

second-hand. (BOB SAWYER, The Pickwick Papers.)

AS Mr. W. A. Harding has pointed out, eleven species of fresh-water leeches occur in these islands. But one of these, the Hirudo medicinalis, seems to be vanishing, and yet it is just the one we should cherish and preserve.

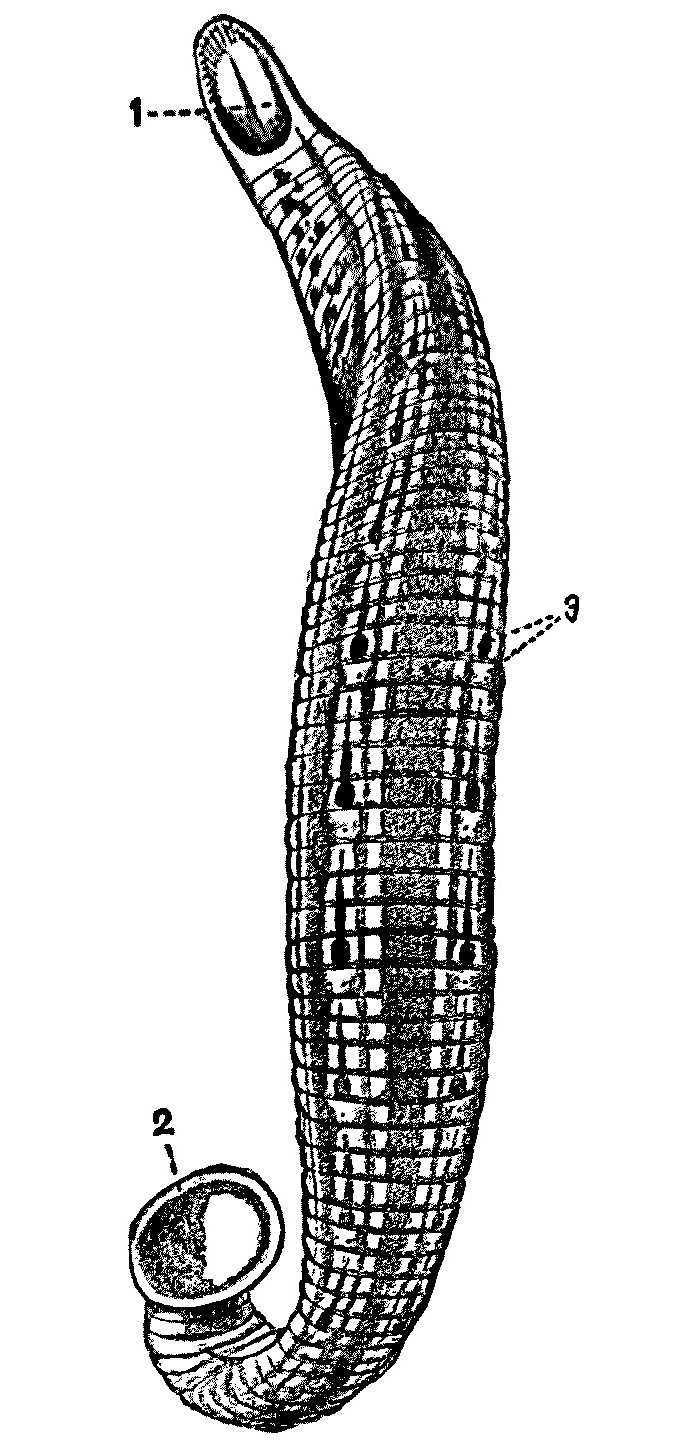

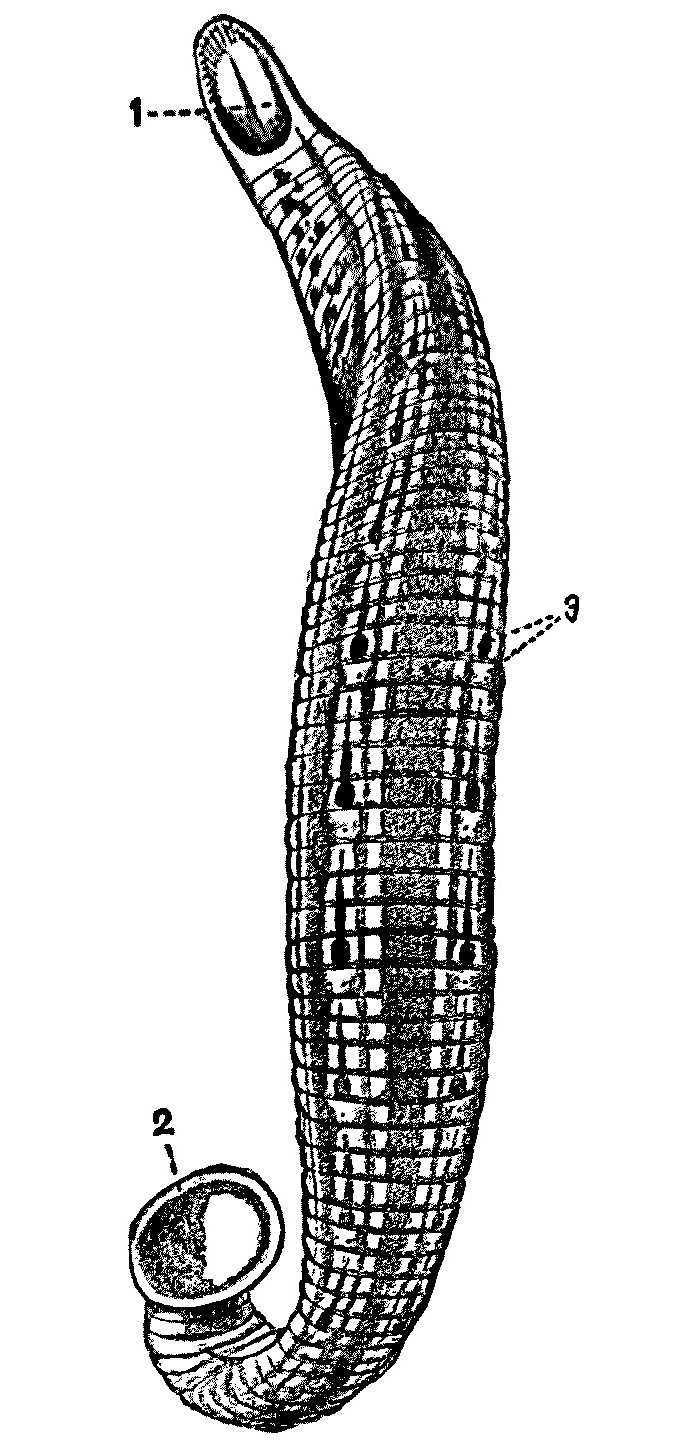

FIG. 48.—Hirudo medicinalis; about life size. 1, Mouth; 2, posterior sucker; 3, sensory papillae on the anterior annulus of each segment. The remaining four annuli which make up each true segment are indicated by the markings on the dorsal surface.

There are people who do not like leeches. This is shown by the agitation amongst the travellers in an omnibus, as depicted in Punch by Leech, years and years ago, when an old gentleman had upset a bottle of them in their midst. But the medicinal leech, which is our theme, is really the friend of man and of the soldier, and is a beneficial and not a harmful animal. There are, of course, other leeches in our rivers and in our seas, but of the latter our knowledge is scanty and it is difficult to increase it at present—at any rate, in the Channel or in the North Sea. In any case the marine leeches in our island-waters have no human interest except the influence they exercise on our fish-food supply, and this is practically negligible.

Zoologically speaking, leeches are undoubtedly degenerate earth worms (Oligochaeta); and some very interesting ‘Zwischenformen’—like Mr. Vincent Crummles, I am ‘not a Prussian’; but in spite of the war, we may as well employ a useful term captured from the enemy—have been found in Russia and Siberia: forms which combine many of the characters of the Oligochaeta and the Hirudinea. Possibly the degeneracy which leeches are said to exhibit is associated with a semi-parasitic habit of life. But a semi-parasitic habit does not apply to all leeches—in fact, it applies but to few genera; there are many others, equally degenerate—if degenerate they be—who have no trace of semi-parasitism.

A curious thing about leeches is that all the varying genera have the same number of somites or segments; and though some of these segments or somites are masked and fused, when analysed by the number of segments in the embryo, by the number of the nerve ganglia, and so on, leeches seem always to have thirty-four such segments. These do not correspond with the rings or annulations so visible on the outside; but a certain number of these annulations, varying in each species, ‘go’ to each somite, and so constant are these numbers that it would not be very difficult to represent any given species of leech by a mathematical formula.

The known species readily fall into two sub-orders: (1) The Rhynchobdellae, which are marine and fresh-water leeches with colourless blood, with no jaws, and with an extensile proboscis; and (2) the Arhynchobdellae, which are all fresh-water or terrestrial, with red blood, and generally with jaws. There is no extensile proboscis, and the anterior sucker has a ventral aspect, and is in no way distinct from the body. There are always in this group seventeen pairs of nephridia or kidneys. We shall have mostly to do with the latter sub-order.

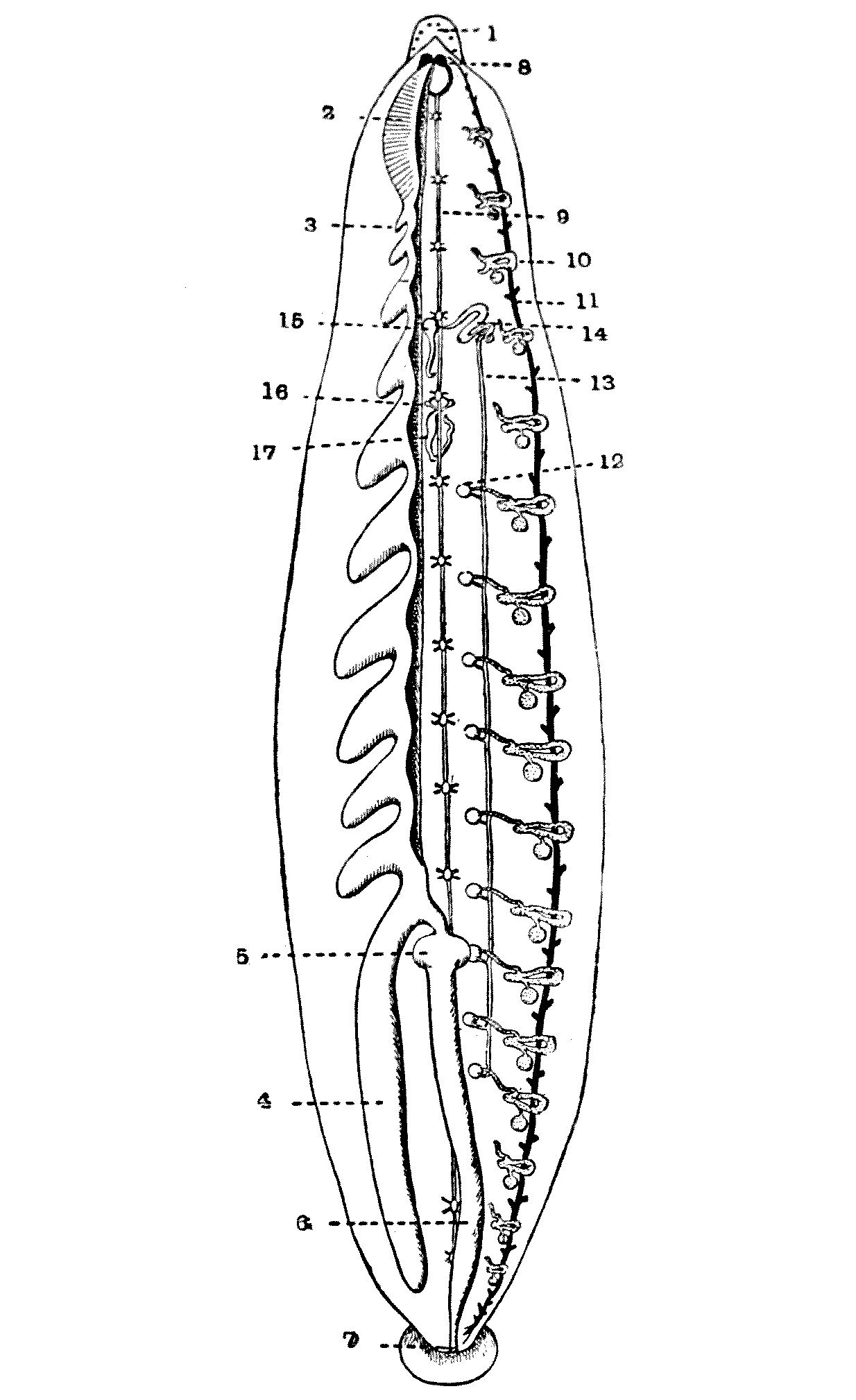

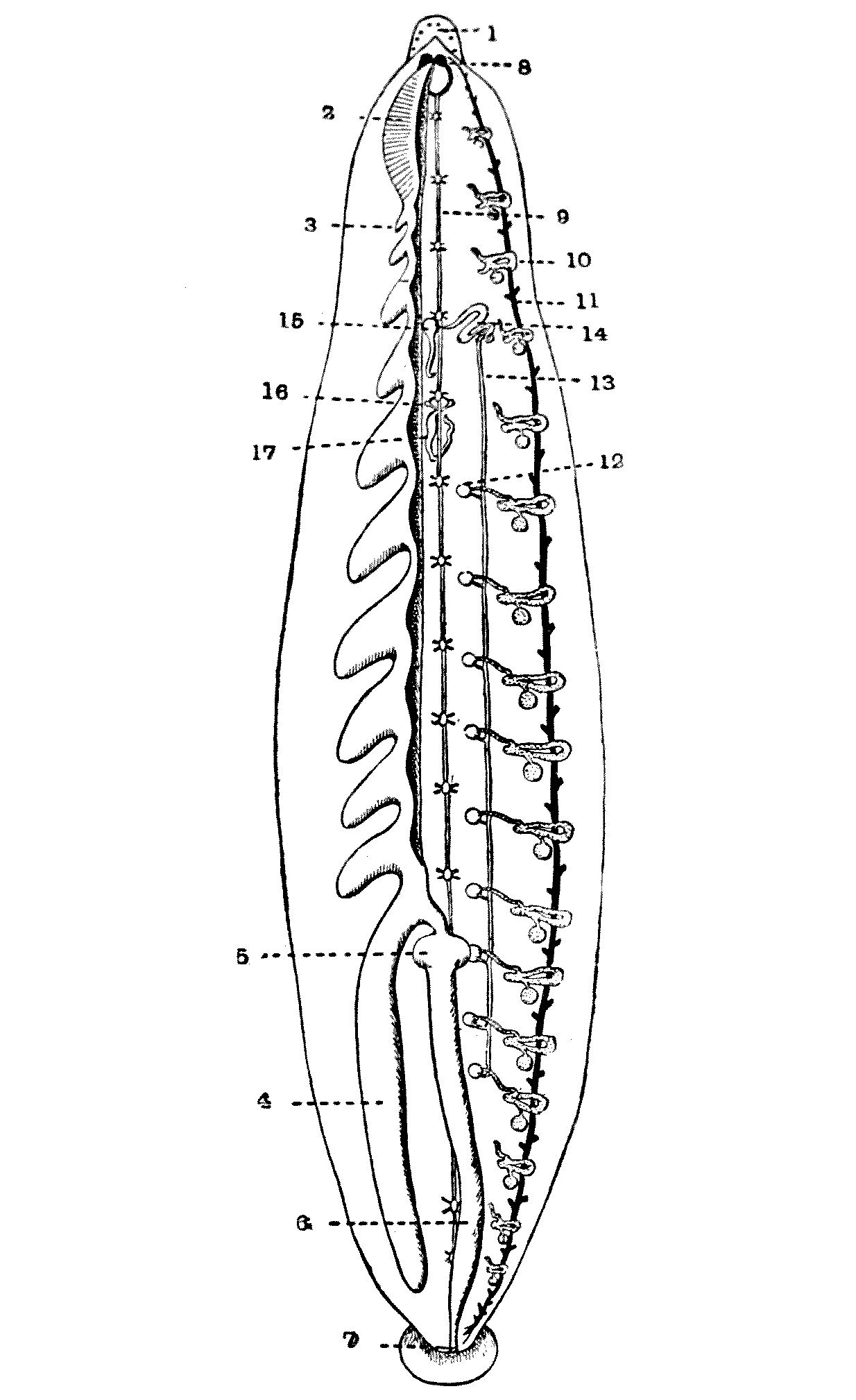

FIG. 49.—View of the internal organs of Hirudo medicinalis. On the left side the alimentary canal is shown, but the right half of this organ has been removed to show the excretory and reproductive organs. 1, Head, with eye-spots; 2, muscular pharynx; 3, first diverticulum of the crop; 4, eleventh diverticulum of the crop; 5, stomach; 6, rectum; 7, anus; 8, cerebral ganglia; 9, ventral nerve-cord; 10, nephridium; 11, lateral blood-vessel; 12, testis; 13, vas deferens; 14, prostate; 15, penis; 16, ovary; 17, uterus, a dilatation formed by the conjoined oviducts.

Hirudo medicinalis, the medicinal leech, is found in stagnant waters throughout Europe and the western parts of Asia. It is rather commoner in the southern parts of Europe than in the north. It used to be common enough in England, where at one time, it was bred; but already a hundred years ago its numbers were diminishing.

In a treatise on the Medicinal Leech, published by J. R. Johnson in the year 1816, he records: ‘Formerly the species was very abundant in our island; but from their present scarcity, owing to their being more in request among medical men, and to the rapid improvements which have of late years taken place in agriculture—particularly in the draining and cultivation of waste lands—we are obliged to receive a supply from the Continent, chiefly from Bordeaux and Lisbon.’ In his time he considered that for every native leech employed at least a hundred foreigners were used.

The same scarcity was very apparent to the poet Wordsworth, whose insatiate curiosity is recorded in the following lines in 1802—Wordsworth was always asking rather fatuous questions:—

My question eagerly did I renew,

‘How is it that you live, and what is it you do?’

He with a smile did then his words repeat:

And said that, gathering leeches, far and wide

He travelled; stirring thus about his feet

The waters of the pools where they abide.

‘Once I could meet with them on every side;

But they have dwindled long by slow decay;

Yet still I persevere, and find them where I may.’

In Europe, where the leech was once very abundant, it is now chiefly confined to the south and east, and in Germany it is still found in the island of Borkum and in Thuringia—but just now we need not trouble ourselves very much about their distribution in Germany.

In 1842, leeches were occasionally found in the neighbourhood of Norwich, and there are villagers still living in Heacham in Norfolk who remember the artificial leech-ponds. In the middle of the last century the medicinal leeches ‘of late years ... have become scarce.’ At about the same time, it is also recorded that they were becoming scarce, though still to be found, in Ireland. Apparently this species is now almost extinct in England, although I know of a naturalist who can still find them in the New Forest, but he will not tell where. If they were getting scarce in the beginning of the nineteenth century they are far scarcer now[14]—for there is no leech in London—at least, there are only a dozen or two, and they, like those of the firm ‘Sawyer late Nockemorf,’ are second-hand and I have heard that there is a similar shortage in North America. And yet leeches are wanted by doctors!

Harding tells us that:—

Hirudo medicinalis is not the only leech which has been used in phlebotomy. Hirudo troctina (Johnson, 1816), occurring in North Africa and in Southern Europe, where it is perhaps an introduced species, was largely imported at one time for medical uses....

Several other species have been used for blood-letting in different countries. Limnatis (Poecilobdella) granulosa in India, Liostoma officinalis in Mexico, Hirudo nipponia in Japan (Whitman), and Macrobdella decora in the United States (Verrill), are or have been used in phlebotomy.

‘Our chief hope seems to lie in India.’ These words I wrote in October 1914, and my hopes were justified. Owing to the energy of Dr. Annandale of the Indian Museum, and the anxious care of the authorities of the P. & O. Company, I was able to land, early in the present year, a consignment of many hundred Limnatis granulosa—in sound health, good spirits, and obviously anxious to do their duty.

Leeches are still used much more than the public are aware. One pharmaceutical chemist in the West End of London tells me he sells between one and two thousand a year; and as they are bought wholesale at about one penny each and sold retail at about sixpence, there is some small profit.

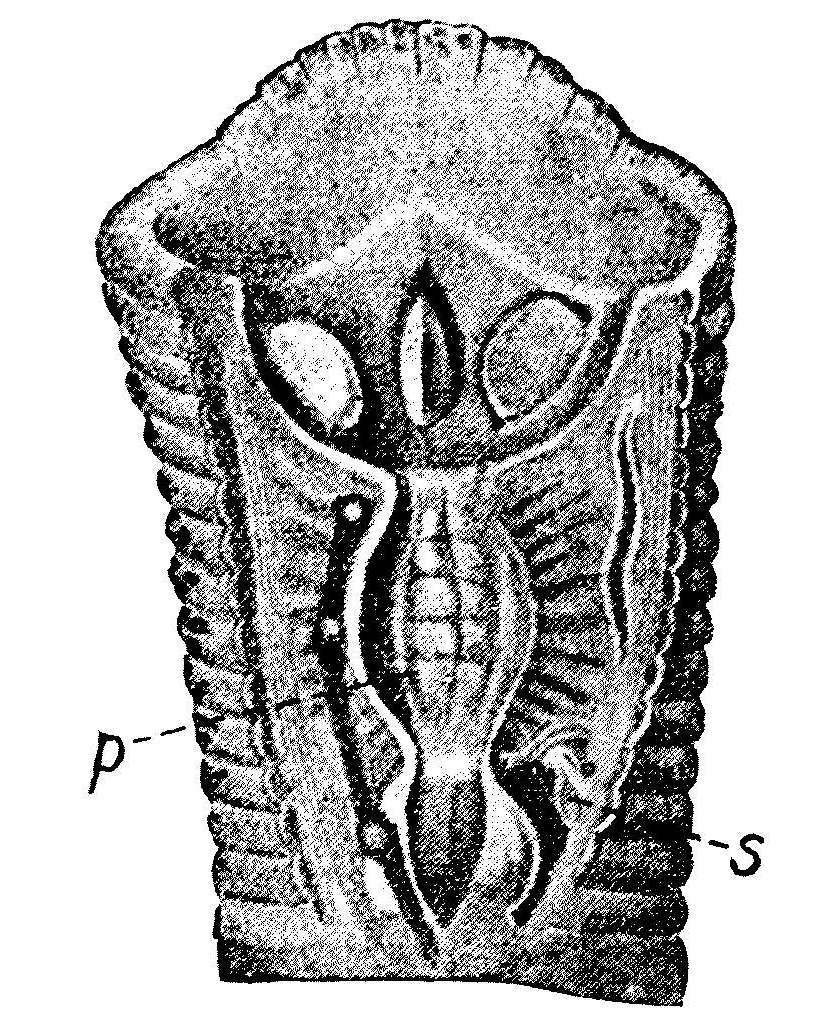

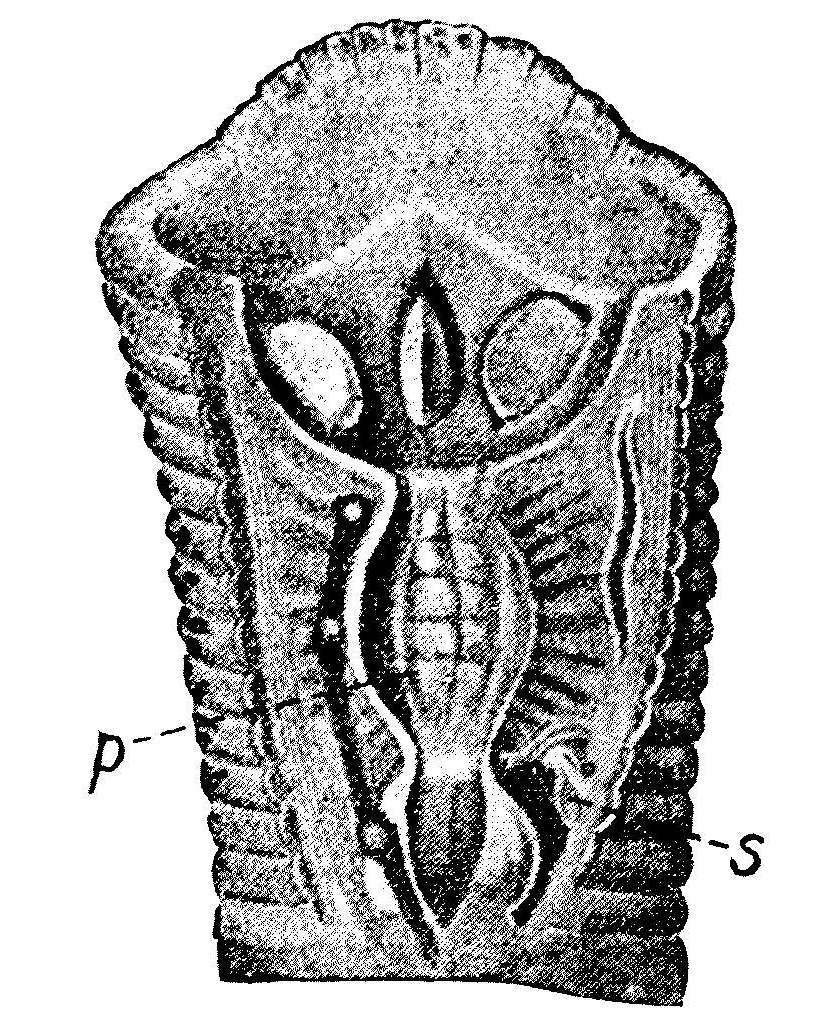

FIG. 50.—Head of a leech, Hirudo medicinalis, opened ventrally to show the three teeth and the pharynx p, with its muscles; s, a nephridium.

Leeches were well known to the ancients, and it would be easy to quote case after case from the classical medical authorities of their use in fevers and headaches and for many ill-defined swellings. They were frequently used for blood-letting where a cupping-glass was out of the question. With his curious uncritical instinct, Pliny records that the ashes of a leech sprinkled over a hirsute area or formed into a paste with vinegar and applied to the part will remove hair from any region of the body. Leeches were also used by the Greek and Roman physicians in angina—especially when accompanied by dyspnoea.

Probably the traffic in leeches reached its height in the first half of the nineteenth century. Harding reminds us that in the year 1832 Ébrard records that 57,500,000 of these annelids were imported into France, and by this time the artificial cultivation of leeches had become a very profitable industry. Although in a small way leeches may have been cultivated in special ponds in Great Britain, the English never undertook the industry on a large scale. In Ireland the natives used to gather the leeches in Lough Mask, and other inland lakes, by sitting on the edge of the pool dangling their legs in the water until the leeches had fastened on them. But the native supply was totally inadequate, and the great majority of leeches used in this country were then imported. In 1842 Brightwell mentions a dealer in Norwich who always kept a stock of 5000 of these annelids in two large tanks. The traffic, as we have seen, was very considerable.

The French leech-merchants recognised five classes, as follows:—

- Les filets ou petites Sangsues, qui ont de un à cinq ans;

- Les petites moyennes, qui ont de cinq à huit ans;

- Les grosses moyennes, qui ont de huit à douze ans;

- Les mères Sangsues ou les grosses, qui sont tout à fait adultes;

- Les Sangsues vaches, dont la taille est énorme.

They also recognised many colour-varieties, of which we need only mention the speckled, or German leech—‘Sangsues grise medicinalis,’ with a greenish-yellow ventral surface spotted with black, and the green Hungarian leech with olive-green spotted ventral surface. Both are merely colour-varieties of Hirudo medicinalis—a species which shows great variation in colour, and often forms colour-races when bred artificially.

The varying sizes of the five categories mentioned above may be seen by the fact that one thousand of ‘les filets’ weigh from 325 to 500 grammes, one thousand of ‘les petites moyennes’ weigh 500 to 700 grammes, one thousand of the ‘grosses moyennes’ weigh 700 to 1300 grammes, and one thousand of the ‘grosses’ 1300 to 2500 or even to 3000 grammes. Whereas one thousand of ‘les vaches’ weigh up to 10 kilograms, and sometimes even more. To increase their weight the dishonest dealer sometimes gives them a heavy meal just before selling them.

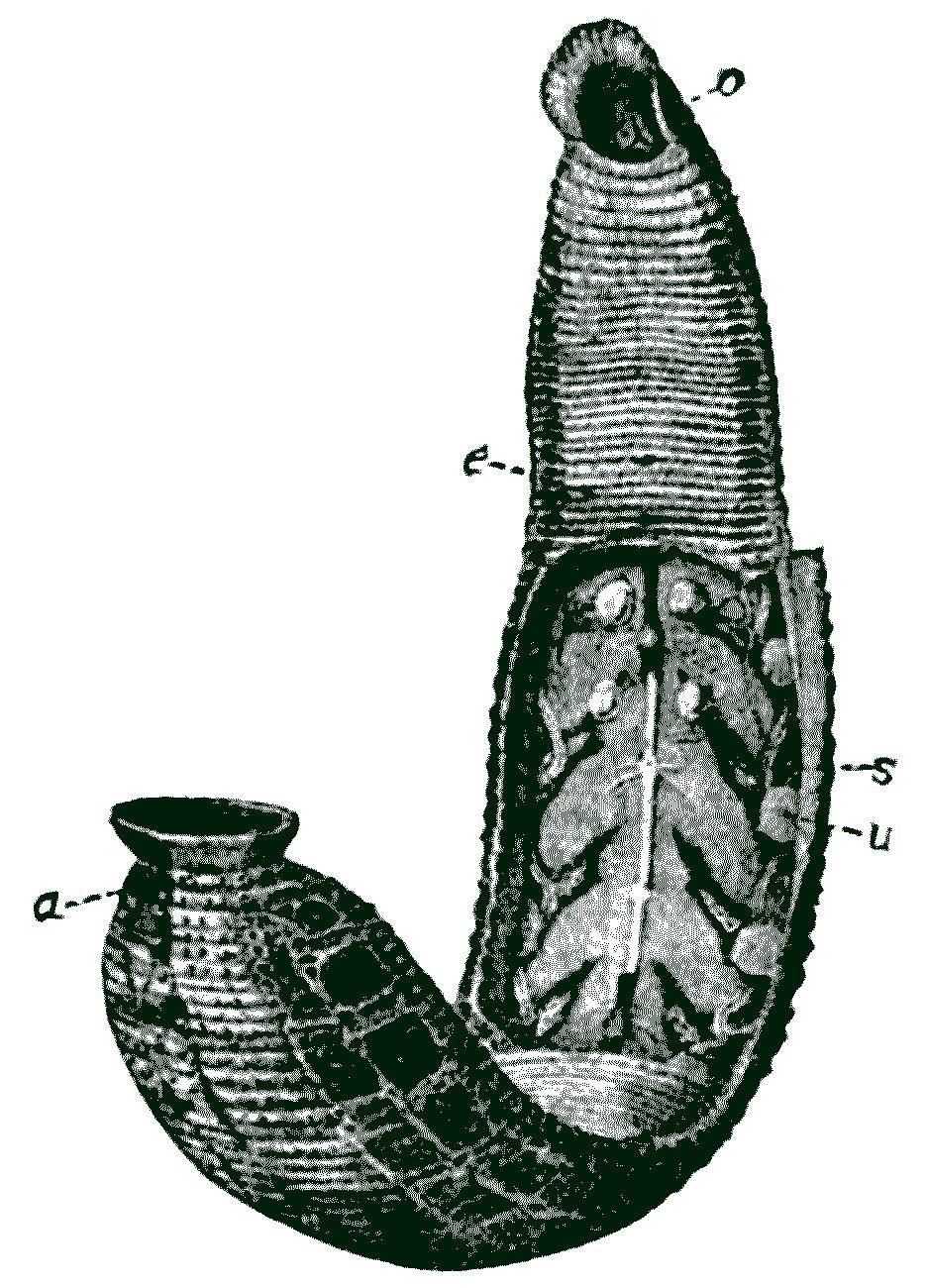

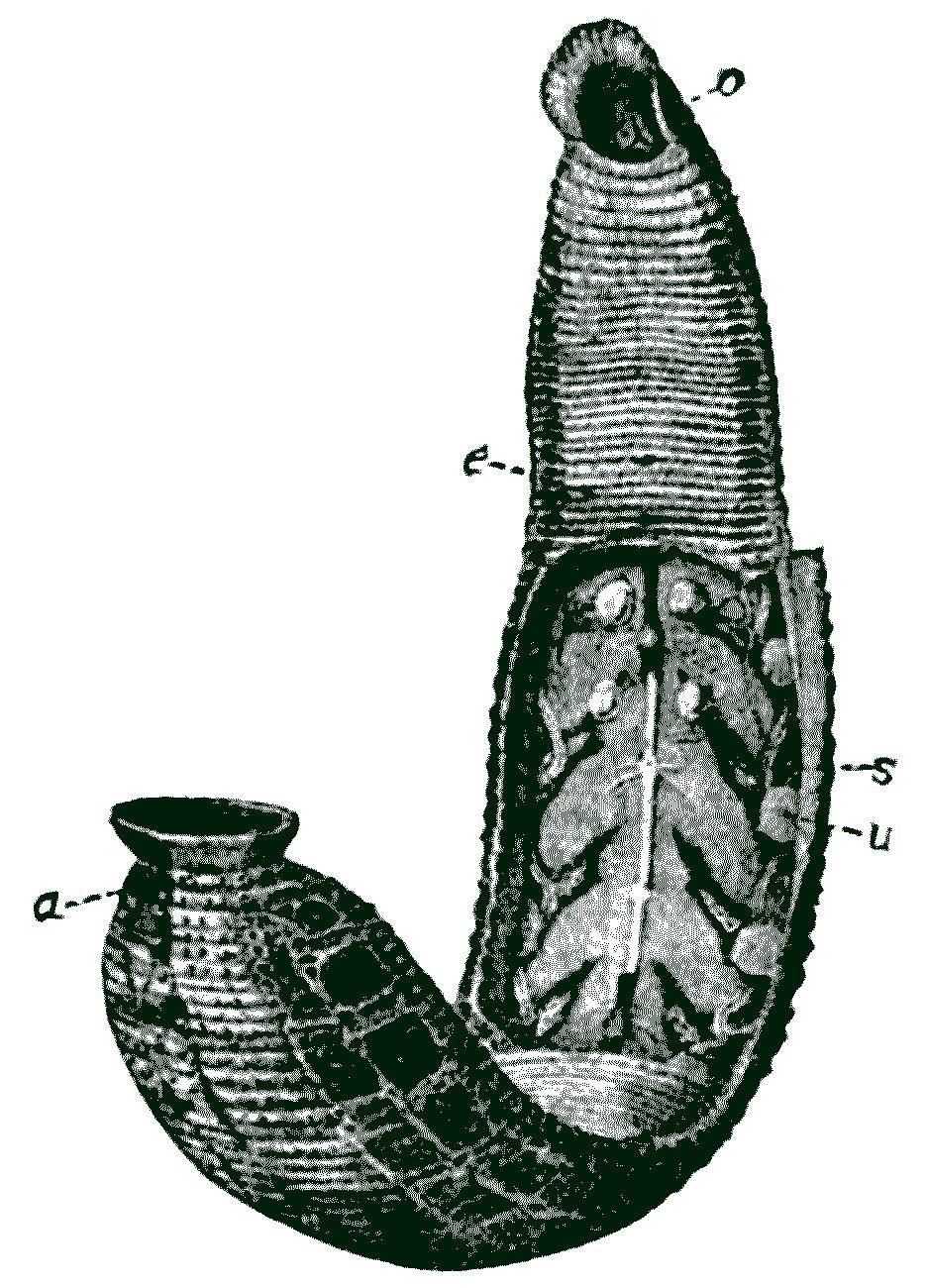

FIG. 51.—Hirudo medicinalis. o, Anterior sucker covering triradiate mouth; e points to an annulus midway between the male and female openings, s to a nephridium, u to the bladder of the latter; a, anus. Four testes and four lateral diverticula of the crop are also shown.

They were transported from place to place in casks half filled with clay and water, or in stone vases full of water. Sometimes they travelled in sacks of strong linen, or even of leather, and these had to be watered from time to time. Another mode of conveying them was to place them in baskets full of moss or grass soaked in water, but care had to be taken lest they should escape. These baskets, again, could not be packed one upon another, or the leeches were crushed. In the old days each sack often weighed 20 to 25 kilograms; and travelling thus, suspended in a kind of hammock, dans une voiture ou fourgon, from Palota near Pesth, they reached Paris in from twelve to fifteen days.

They generally travelled via Vienna to Strassburg, where twelve great reservoirs, appropriately placed near the hospital, received them, and here they rested for awhile. Others collected in Syria and Egypt came by ship to Trieste, whence they are sent to Bologna, to Milan, and to Turin, or by water to Marseilles. Marseilles also received directly by sea the leeches from the Levant and Africa, and expedited them to Montpellier, Toulouse, and many another town in the south.

The best time of year for their journey was found to be the spring and autumn. They were more difficult to manage in the summer, and they were all the better for having a rest every now and then, as they used to do at Strassburg. There were times when consignments of from 60,000 to 80,000 a day used to leave Strassburg for Paris. In 1806 a thousand leeches in France fetched 12 to 15 francs; but in 1821 the price had risen to 150 to 200 and even 283 francs. In the latter year they were retailed at 20 to 50 for 4 to 10 sous.

As in England, however, for the most part the artificial cultivation of leeches is diminishing in France, though half a century ago leech-farms were common in Finistère and in the marshes in the neighbourhood of Nantes. There were some years when, if the season was favourable, the peasants carried to market 60,000 a day. Spain and Portugal also furnished leeches for a long time; but by the middle of last century the Peninsula had become almost depleted. But some leeches were still at that period being received from Tuscany and Piedmont. Perhaps the richest fields which still exist are the marshy regions in Hungary.

It will be observed that, probably without their knowing anything at all about it, General Joffre, General von Kluck, Field-Marshal French, the Grand Duke Nicholas, General von Hindenburg are fighting on some of the best leech-areas in Europe—a point to which we shall return when dealing with the leeches of the Orient.

One wonders what the leeches think of it all!