Chapter Seven

TWO VENETIAN STATUES

IN two of the public squares of Venice the statues, in bronze, of two of her heroes are set up, the one of a man of war, the other of a comedian: in the Campo di SS. Giovanni e Paolo the statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, in the Campo di San Bartolomeo that of Carlo Goldoni. The first is a warrior on horseback in full armour, uplifted high above the square, disdaining the companionship of the puny mortals who saunter without a purpose to and fro under his feet. Horse and rider stand self-sufficient and alone; one spirit breathes in both: in the contour of the stern face of the warrior, with its massive chin and proudly disdainful lip, in his throat with the muscles standing out like ropes upon it, and in the sweep of his capacious brow, under which the keenly penetrating eyes hold their object in a grip of iron; and, for the horse, in every line of his superbly curving neck, in the acute serenity of his down-looking eye, and in each curling lock of his mane that seem as if moved together by one controlling impulse. How clear the outline of his skull, everywhere visible beneath its fine covering of flesh and muscle! and his body, like the body of his master, how perfectly responsive an instrument it is! There is nothing here of that wild disorder of the beast untamed, which is mistaken sometimes for strength. The hand of Colleoni is light upon the bridle, the horse glories in a subjection that is itself a triumph: he and his master are one. Do but compare this for a moment with the prodigious mass, the plunging man and beast, that overlook the Riva degli Schiavoni—Victor Emanuel on horseback. It is not altogether an arbitrary contrast; the two great monuments seem to represent Venice before the fall and Venice after. What unity of purpose, what hope of conquest is there in those monstrous figures on the Riva? Beneath this redundancy of flesh and armour how shall they prevail against the world? They are not only different in degree, they are of a different species from Verocchio’s horse and rider. The spirit of the first Renaissance is in every line of his great statue—its strength, agility and decorative skill. How studied is the symmetry, the static perfection of the whole! how strongly and yet how delicately he emphasises the rectangular framework of the design! The rod of Colleoni, the trappings of his horse, the tail and legs and body-line—each is made contributive, while the backward poise of the rider balances the forward motion of the horse, and all is thus drawn into the scheme. It is all willed, but with that spontaneity of will which men call inspiration.

This statue, which so marvellously sums up in sculpture the central aim of Venice as a state in the fifteenth century, offers an instructive contrast to that in the Campo di San Bartolomeo, where the comedian Goldoni, though raised above the level of the square, still seems a companionable part of the life that passes around him, moving in its midst as he moved amid the life of the eighteenth century in Venice, meditating upon it, observing, loving it, faithfully and fearlessly recording it. Marked by a realistic fidelity and insight worthy of a greater age, Dal Zotto’s statue of Goldoni is in its own way itself a masterpiece and one of the noblest works of modern art in Venice, full of sympathy and understanding and admirable in execution. The sculptor might seem to have lived as an intimate with Goldoni, and the realism of his treatment suits the subject singularly well. The comedian is not aloft upon a pedestal, remote from men, in glorious aloofness; he is raised but slightly above our heads, not much observed of the crowd, but observing all. Briskly he steps along, in buckled shoes, frilled shirt and neckerchief, his coat flying open, and a book or manuscript bulging from the pocket of it, his waistcoat slackly buttoned, his cocked hat tipped jauntily upon his forehead over his powdered periwig. As he goes he crushes his gloves with one hand at his back and with the other marks progress with his cane. It is a strong, taut little figure, tending to roundness, with a world of suggestiveness in every motion, an admirable mingling of thought and humour in the face that laughs down on this strange, grotesque, conventional, lovable Venice. What a strange contrast is this, of the slippered sage of the eighteenth century, who houses the swallows in the loose folds of his slouch hat, and the armed hero of the fifteenth, whose every muscle is alert, responsive to the stern controlling will! Goldoni is a sage upon a different platform, meditating upon a different world. His Venice is the Venice of Longhi; she has become pedestrian; she has become a theme for comedy. Comedy might have found plentiful food, no doubt, in the Venice that employed Colleoni, the Venice of the first great painters. There is a fund of humour and whimsicality in the strangely fascinating faces of Carpaccio’s citizens. Yet try to picture them held up to ridicule by one of themselves upon the stage, and the imagination faints; the thing is inconceivable. In Goldoni’s age the interest of life was shifted to another field, and he stands as the central figure, the leader in a new campaign, representative not of its vices or its vanities or its follies, but of the solid virtues of which these are the shady side. He is one of those happy spirits which the reactionary age of small things produced, not only in Italy but everywhere in the eighteenth century; a spirit of clear, calm insight and capable judgment, neither enamoured of the life of his small circle nor embittered against it, content to live in the midst of it in serenity and truth.

Goldoni, Colleoni, each is representative of a period in the history of the Republic, periods widely separated in temper and in time, and yet related intimately; so intimately indeed that the period of which Goldoni is the master-spirit is actually foreshadowed in the very presence of the superb warrior of the other public square. To study the process of the growth and the decadence of the Republic is to find that there is no convenient preconceived theory with which it will fit in; it rebels against such manipulation, as everything individual rebels against the ready-made. We need rather to look upon Venice as upon a plant that springs and comes to its perfection and fades slowly away, changing and developing in indefinable gradations, showing at every stage some surprising revival from the past, some strange anticipation of the future. In the fifteenth century itself, while the earliest artists were at work for Venice at Murano, and Carpaccio was as yet unborn, Venice already bore about with her the seeds of her decay. In fact, the growth of her art coincides with the slow relaxation of her hold upon the bulwarks of her policy both at home and abroad. The election of Foscari as Doge in 1423 marks a moment of change in Venetian life and government, indicated by the substitution of the title Signoria for that of Commune Venetiarum, and by the abolition of the arengo—yet Carpaccio has still his grave citizens to portray, and Ursula sleeping the sleep of infancy. Among the exhortations which tradition has handed down to us as addressed from time to time to the Venetians by Doge or by ambassador is that supposed to have been spoken on his death-bed by Foscari’s precursor, the Doge Tommaso Mocenigo. It might have been spoken for our instruction, instead of as a reminder to his own subjects of what they knew so well, so vivid an impression is to be derived from it of the inner life of Venice during the first thirty years of the fifteenth century. Whether legendary or not, these exhortations have something significant and individual about them which really illuminates; it is as if a light were suddenly flashed into a vast room, pressing our vision upon one point, providing a nucleus of knowledge about which scattered ideas and impressions may group themselves intelligibly. Whatever they are, they are not the fabrication of a later time which has lost understanding of the spirit that animated the past. If the portrait they give is imaginary, they have seized upon the salient features and endowed them with a vitality which the photograph, however literal, too often lacks. Mocenigo’s farewell address is an impressive portico opening upon a new period in the career of Venice, a strange trumpet-note of ill omen on the threshold of her greatest glory. Behold, he says, the fulness of the life you have achieved, of the riches you have stored; turn now and preserve it; there is peril in the path beyond; there is twilight and decay and death. Your eyes, full of the light, have no knowledge of the shadow; but mine, dim now with age, have known it, and its grip is upon my limbs. Venice heard but might not heed his warnings. The sun himself must rise and fulfil his day and set. Decay is in each breath that the plant draws in; it cannot crystallise the moment; inexorably it is drawn onwards to maturity and death. It was inevitable for Venice that as her strength increased her responsibilities should increase with it; perforce she must turn her face to land as well as sea. She could not remain alone, intent only on nourishing and developing her individual life. In proportion to her greatness she must attract others to her, and the circle of her influence must widen till it passed beyond her own control. The dying words of Mocenigo came too late. A temporary delay there might have been; there was no turning back. Venice had been drawn already into the vortex of European mainland politics, and she could not stand aside. In our own colonial policy we are continually confronted with the problem of aggression and defence. In reality there is no boundary between the two, or the boundary, if it exists, is so fine that the events of a moment may obliterate it. St. Theodore carries his shield in his right hand and his spear in the left; and an old chronicler of Venetian glory interprets the action as symbolising the predominance of defence in his warrior’s ideal. Doge Tommaso Mocenigo would have approved the interpretation. But spear and shield cannot exchange their functions. Until the spear is laid aside, it will insist on leading; and Venice had not laid aside the spear, she had furnished herself anew.

“In my time,” says Mocenigo, after a pathetic preliminary avowal of his obligations to Venice and of the humble efforts he had made to discharge them, “in my time, our loan has been reduced by four millions of ducats, but six millions still are lacking for the debt incurred in the war with Padua, Vicenza, Verona.... This city of ours sends out at present ten million ducats every year for its trade in different parts of the world, with ships and galleys and the necessary appointments to the value of not less than two million ducats. In this city are three thousand vessels of from one to two hundred anforas burden, carrying sixteen thousand mariners: there are three hundred vessels which alone carry eight thousand mariners more. Every year sail forty-five galleys, counting small and great craft, and these take eleven thousand mariners, three thousand captains and three thousand calkers. There are three thousand weavers of silk garments and sixteen thousand of fustian.... There are one thousand gentlemen with incomes ranging from seven hundred to four thousand ducats. If you go on in this way, you will increase from good to better, you will be lords of riches and of Christendom. But beware, as of fire, of taking what belongs to others and making unjust war, for these are errors that God cannot tolerate in princes. It is known to all that the war with the Turk has made you brave and valorous by sea, ... and in these years you have so acted that the world has judged you the leaders of Christendom. You have many men experienced in embassies and government, men who are perfect orators. You have many doctors in diverse sciences, lawyers above all, and for this reason many foreigners come to you for judgement in their differences and abide by your decisions. Take heed, therefore, how you govern such a state as this, and be careful to give it your counsel and your warning, lest ever by negligence it suffer loss of power. And it behoves you earnestly to advise whoever succeeds me in this place, because through him the Republic may receive much good and much harm. Many of you incline to Messer Marino Caravello; he is a worthy man and for his worthy qualities deserves that rank. Messer Francesco Bembo is an honest man, and so is Messer Giacomo Trevisan. Messer Antonio Contarini, Messer Faustin Michiel, Messer Alban Badoer, all these are wise and merit it. Many incline to Messer Francesco Foscari, not knowing that he is an ambitious man and a liar, without a basis to his actions. His intellect is flighty; he embraces much and holds little. If he is Doge, you will always be at war. The possessor of ten thousand ducats will be master but of one. You will spend gold and silver. You will be robbed of your reputation and your honour. You will be vassals of infantry and captains and men-at-arms. I could not restrain myself from giving you my opinion. God help you to choose the best, and rule and keep you in peace.”

Mocenigo’s warning was disregarded. But although Foscari was made Doge, Venice did not rush into war. In spite of repeated efforts on the part of the Florentines to secure an alliance, the traditions of the old peace policy were tenaciously adhered to during the first years of the new reign. It was the temptation to secure Carmagnola as leader of her forces which finally overcame her scruples. Foscari’s discourse on this occasion, as reported by Romanin, is a curiously specious mingling of philanthropy and self-interest. Reading between the lines, we understand from it something of Mocenigo’s fears at the prospect of his election. The passion of empire is in his heart. Venice, whom eulogists loved to represent as the bulwark of Europe against the infidel, is now to be the champion of down-trodden Florence. It is the sword of justice that she is to wield. We are reminded of Veronese’s allegory—Venice seated upon the world, robed in ermine and scarlet, her silver and her gold about her, her breast clasped with a jewelled buckler, round her neck the rich pearls of her own island fabric, on her head the royal crown. Her face is in the shadow of her gilded throne and of the folds of the stiff rose satin curtain, as she looks out over the world, over the universe, from her lofty seat on the dark azure globe. The lion, the sword and the olive branch are at her feet. What is she dreaming of, this Venice of the soft, round, shadowed face? Is it of peace, or of new empire? Is it to the olive bough or to the sword of justice that she inclines? In a neighbouring fresco, Neptune, brooding in profound abstraction beside his trident, deputes to the lion his watch; but Mars of the mainland is alert, on foot, and his charger’s head from above him breathes fire upon his brow.

“You will be the vassals of captains and men-at-arms.” There was a note of prophecy in Mocenigo’s closing words, and it is indeed a question, in face of Verocchio’s superb warrior—who was the prince and who the vassal, who the servant and who the master. Colleoni’s triumph at his grand reception in Venice can scarcely have been the triumph of a mere man-at-arms. Studying the magnificent reserve of strength in his grandly moulded face and neck, we feel Venice must rather have acknowledged that an Emperor had descended in her midst. Little wonder that such a man dared ask a place on the Piazza of St. Mark itself! The period of his command embraced some of the most brilliant successes of the Venetian arms on land. Difficulties and perils that seemed insurmountable were yet surmounted by a mind possessed of supreme qualities of judgment, daring and nobility. Singularly akin, indeed, to Venice herself was this man who had a key to the minds of his antagonists, who read their secrets and forestalled their actions: it is not strange that he was dear to her. Though a professional soldier and no Venetian born, he could act as a worthy representative of Venice, and there might seem small fear of ruin for a Republic that could so choose her servants. But Colleoni had fought against the Lion and set his foot upon its neck, and the Lion had been constrained to turn and ask his service of him, the highest tribute it could offer, the completest confession of its defeat. And Colleoni could respect and be faithful to such a paymaster: for twenty years he led the Republic on land, and was never called to render an account before her judgment-seat. Magnanimously at his death he absolves her of all her debts to him, makes her two grand donations, then, by his own wish, towers over Venice, a paid alien, her virtual master, yet such a master as she was proud to serve. We wonder if this thought came ever to the mind of Verocchio, the Florentine, as he moulded the great figure of the hero: did the imagination please him of Venice the vassal, Venice subjected beneath the horse and his rider?

There was a fête given in honour of Colleoni at Venice in 1455, on the occasion of the bestowing on him the staff of supreme command. To Spino, Colleoni’s enthusiastic biographer and fellow citizen, the episode was portentous, as to one unfamiliar with Venetian traditions in this respect. It had, indeed, a significance he did not dream of; it was the reception not of a victorious fleet, not of an admiring monarch or fugitive pope, but of an army of mercenaries and their leader. Spino tells how Colleoni was accompanied by an escort of the chief citizens of Bergamo, Brescia and other cities of the kingdom that had been committed to his charge; how barges over a thousand were sent from Venice to fetch him and his party from Marghera; how the Venetians came out in flocks to meet him in gondolas and sandolos to the sound of trumpets and other instruments of music, preceded by three ships called bucintori, “of marvellous workmanship and grandeur,” in which were the Doge and Signoria, the senate and other magistrates; and how ambassadors of kings and princes and subject states came to do homage to the new Serenissimo Pasqual Malipiero. He tells, as all the chroniclers of festivals at Venice tell, of the throngs, not only on windows and upon the fondamentas, but upon the house roofs along the Grand Canal; of Colleoni’s reception at San Marco and the display of the sacred treasures at the high altar; and how, as he knelt before the Doge, the staff of his office was bestowed upon him with these words, “By the authority and decree of the most excellent city of Venice, of us the Doge and of the Senate, ruler and captain-general of all our men and arms on land shalt thou be. Take from our hands this military staff, with good presage and fortune, as emblem of thy power, to maintain and defend the majesty, the faith and the judgments of this State with dignity and with decorum by thy care and charge.” For ten days the festivals continued with jousts and tournaments and feats of arms. But all was not fêting and merriment. Colleoni held grave discourses also with the Padri, and “their spirits were confirmed by him,” says Spino, “in safety and great confidence.”

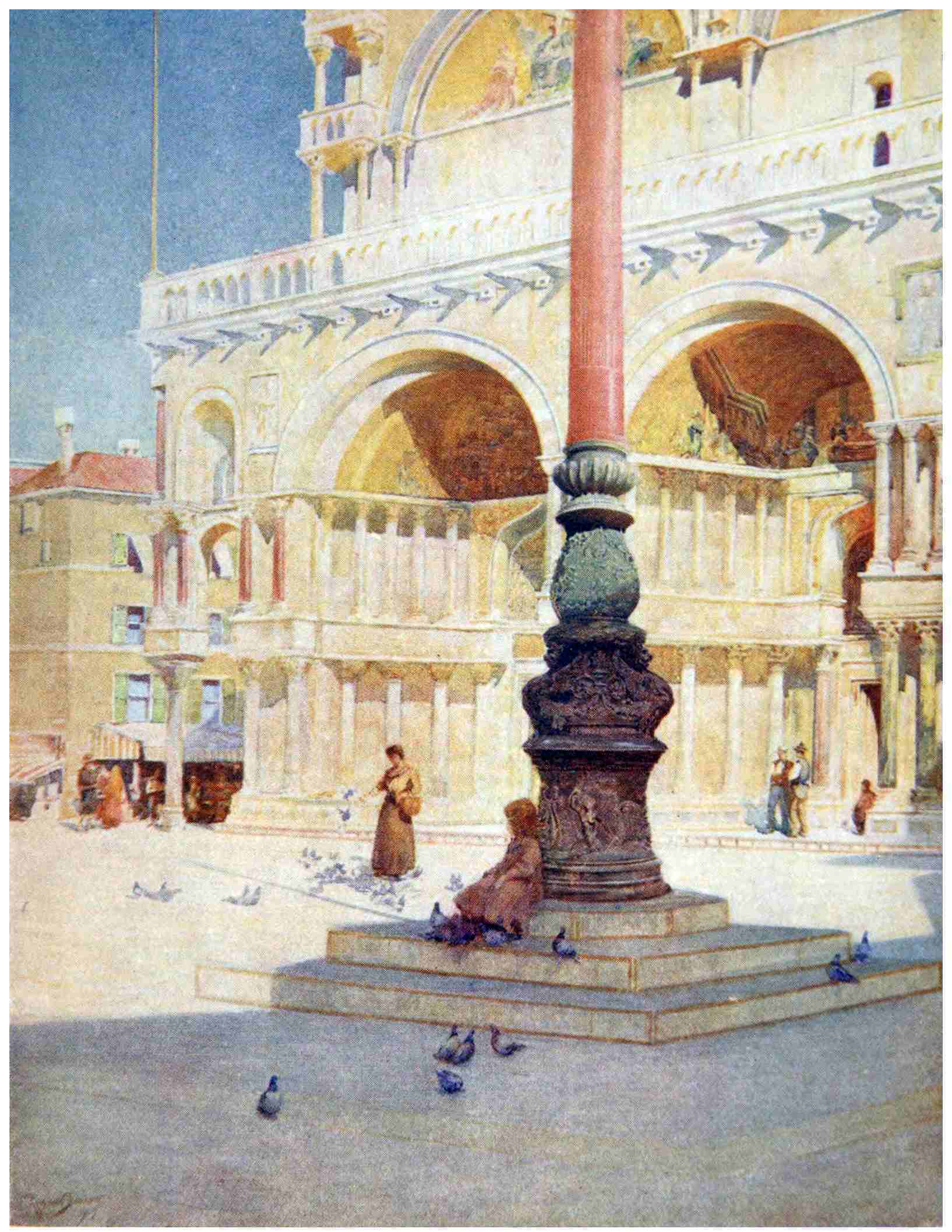

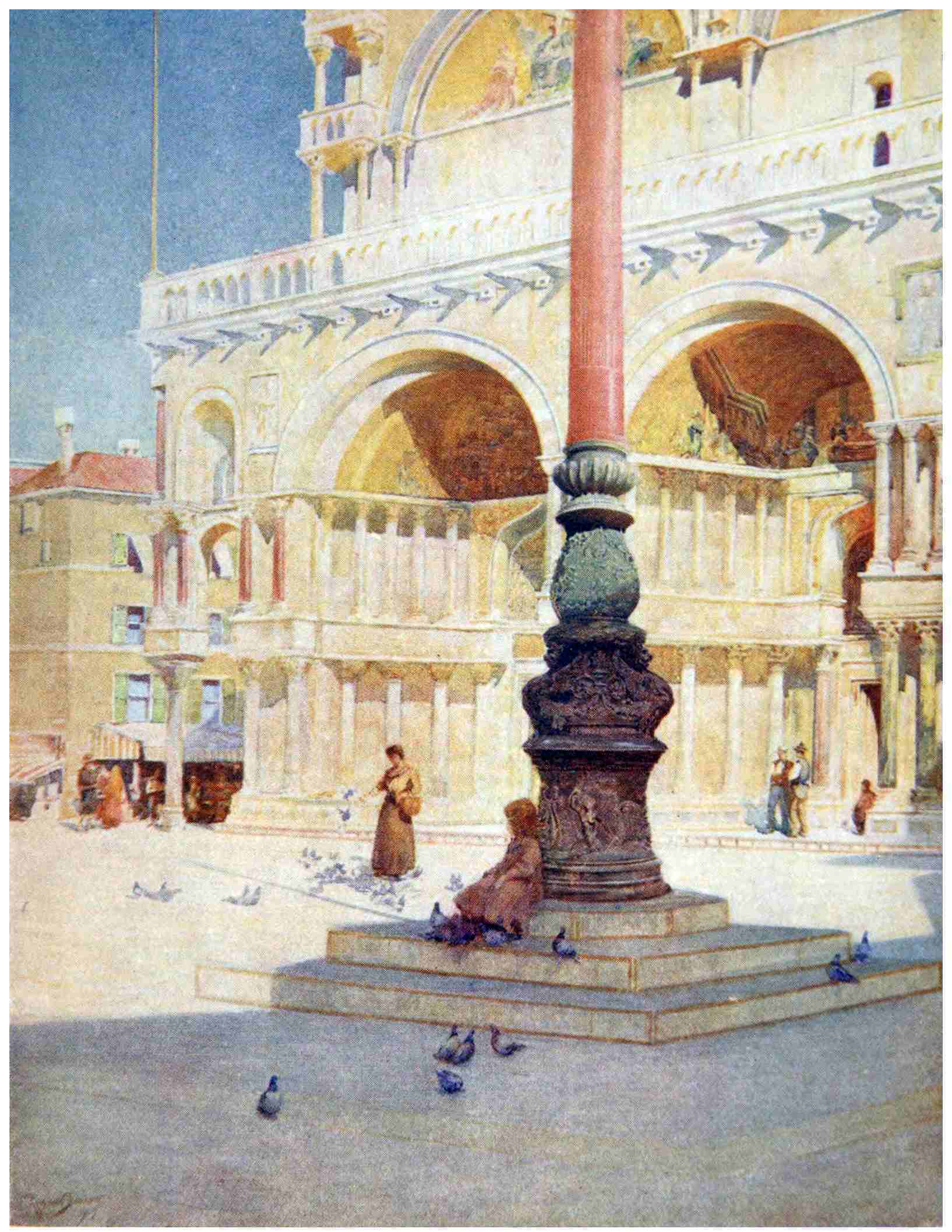

IN THE PIAZZA.

The Venice who could thus do honour to Colleoni her general was a superb Venice, superb as Colleoni himself who in his castle of Malpaga received not only embassies from kings but kings themselves; who, at the visit of Cristierino, King of Dacia, came out to meet him “on a great courser, caparisoned and equipped for war, and he, all but his head, imperially clad in complete armour, attended only by two standard-bearers carrying his helm and lance, while a little further behind followed his whole company of six hundred horse in battle array, with his condottieri and his squadrons, all gloriously and most nobly armed and mounted, with flags flying and the sound of trumpets”; who, besides making rich provision for all his children, built churches, endowed monasteries and left to the Venetians, after cancelling all their debts to him, one hundred thousand ducats of gold. The Venice that employed Colleoni was superb—we have a record of her living features in Gentile Bellini’s marvellous presentment of the procession in St. Mark’s square—the brain as flexible, the jaws as rigid as those of the mighty warrior Verocchio conceived. Yet Spino’s comment on the last tribute paid by the Venetians to their general gives us pause—“confessing to have lost the defender of their liberty.” It was a confession which could still clothe itself triumphantly in the great bronze statue, but there is an omen in the words. In this confession of 1496 is foreshadowed the fall of 1796.

Much has been written of the social life of this Venice of the Fall; there are countless sources for its history in the letters, diaries and memoirs of its citizens and of its visitors, reputable and disreputable; richest sources of all, there are the pictures of Longhi, the comedies of Goldoni. But of the Venice that lay behind this small round of conventions and refinements, laxity and tyranny, perhaps less has been said. Of many avenues by which it might be approached we shall choose one, and since the praise of Colleoni has drawn our attention to the foundations of Venetian power on land, nothing will better serve our purpose than the foundation of her power by sea, that Arsenal which Sansovino described as “the basis and groundwork of the greatness of this Republic, as well as the honour of all Italy.” The Arsenal was, next to San Marco, perhaps the sanctuary of Venetian faith. It was far more than a mere manufactory of arms and battleships. In the celebration of the Sensa its workmen held the post of honour, the rowing of the Bucintoro. Its officers were among the most reputed in the State. The Council of Ten had a room within its precincts. It was entered by a superb triumphal arch, a sight which none who visited Venice must miss. The condition of the Arsenal may well be taken as an index to the condition of Venice herself.

We may set side by side two pictures of the Arsenal, one drawn from a curious little work of early seventeenth century, a time at which, though Venice was moving down the path of her decay, the glorious traditions of the past still found renewal in her present life, and the Venetian fleet was still a triumphant symbol of Venetian greatness; the other from the reports of her officials in the last years before her death. Luca Assarino was one of many guests who had to say to Venice, or to the Doge her representative, “My intellect staggers under the weight of a memory laden with surpassing favours. You received me into your house, did me honour, assisted me, protected me. You clothed yourself in my desires, and promoted them on every occasion; and this not only without having had of me any cause to honour me so highly, but even without having ever seen me.” He feels he cannot better discharge the burden of his gratitude than by shaping some of the emotions inspired in him by his visit to the Arsenal. There is a touch of sympathy and sometimes even a touch of truth and insight under the extravagantly symbolic garb of his appreciation. “Admiring first of all an immense number of porticoes, where as in vast maternal wombs I saw in embryo the galleys whose bodies were being framed, I realised that I was in the country of vessels, the fatherland of galleons, and that those masses were so formidable as to show themselves warriors even in their birth, fortifying themselves with countless nails and arming thus their very vitals with iron. I considered them as wandering islands, which, united, compose the continent of Venetian glory, the mainland of the rule of Christendom. I admired with joy the height of their masts and the size of their sailyards, and I called them forests under whose shade the Empire of the sea reposed and the hopes of the Catholic religion were fortified. And who, I said to myself, can deny that this Republic has subjugated the element of water, when none of her citizens can walk abroad, but that the water, as if vanquished, kisses his feet at every step?” Like all recorders of the glories of Venice, he is struck dumb at certain points by fear of the charge of fabling, but, collecting himself, he proceeds to speak of the trophies and relics, the rows of cuirasses, helmets and swords that remained as “iron memorials to arm the years against oblivion of Venetian greatness. What revolutions of the world, what accidents, what mutations of state, what lakes of tears and blood did not the dim lightnings of those fierce habiliments present to the eye of the observer?... I saw the remains of the Venetian fleet, vessels, that, as old men, weighted no less with years than glory, reposed under the magnificence of the arches which might well be called triumphal arches. I saw part of those galleons to which Christianity confesses the debt of her preservation.... And last, I saw below the water so great a quantity of the planks from which vessels afterwards are made, that one might truly call it a treasury hidden in the entrails of a lake. I perceived that these, as novices in swimming, remained first a century below the surface, to float after for an eternity of centuries; and I remarked that they began by acquiring citizenship in that lake, to end by showing themselves patricians throughout the seas, and that there was good reason they should plant their roots well under water, for they were the trees on which the liberty of Venice was to flower.” In his peroration the eulogist strikes a deeper note. “May it please Almighty God to preserve you to a longest eternity; and as of old the nations surrounding you had so high an opinion of your integrity and justice that they came to you for judgment of their weightiest and most important cases, so may heaven grant that the whole of Christendom may resort always to your threshold to learn the laws of good government.”

We think sadly of his prayer among the records of abuse and corruption in the Arsenal of two centuries later; the Venetian lawyers were still renowned among the lawyers of the world, but the State was no longer capable of teaching the laws of good government to Christendom. The theatre, the coffee-house, the ridotto, the gay villeggiatura were now the main channels of her activity; the tide of life had flowed back from the Arsenal and left it a sluggish marsh. In the arts of shipbuilding no advance had been made, and the cause lay chiefly in an extraordinary slackness of discipline by which workmen were first allowed to serve in alternation and in the end were asked for only one day’s service in the month. Many youths who had not even seen the Arsenal were in receipt of a stipend as apprentices, in virtue of hereditary right. Martinelli tells of porters, valets, novices and even of a pantaloon in a troop of comic actors who were thus pleasantly provided for. There was a scarcity of tools, and even the men in daily attendance at the Arsenal spent their time in idle lounging and often in still more mischievous occupations for lack of anything better to do; disobedience and disloyalty were rife. The Arsenal was used by many as a place of winter resort, as workhouses by the tramps of to-day, and the wood stored for shipbuilding was consumed in fires for warming these unbidden guests, or made up into articles of furniture for sale in the open market. The report of the Inquisitors of the Arsenal, dated March 1, 1874, which Martinelli quotes, is indeed a terrible confession: “One sad experience clearly shows that the smallest concession ... becomes rapidly transformed into unbridled licence. Not to mention the immense piles of shavings, from sixty to seventy thousand vast bundles of wood disappear annually. The wastage of so great a mass of wood, more than the equivalent of the complete outfit of ten or twelve entire ships of the line, is not to be accounted for under legitimate refuse of normal work, but points plainly to the voluntary destruction of undamaged and precious material.” It is scarcely surprising that with so little care for the preservation of discipline in the Arsenal and for the efficiency of its workmen Venice fell behind. The Arsenal had indeed become, as Martinelli says, “a monument of the generous conceptions of the past—a monument, like the church and campanile of San Marco, beautiful, admirable, glorious, but as completely incapable as they of offering any service to the State.” Similar abuses existed also in the manning of the ships. The officers were for the most part idle and incompetent, and the despatches of the Provveditori are a tissue of lamentable statements as to the depression of that which had been, and while Venice was to retain her supremacy, must ever be, the mainstay of her power. There is desertion among the crews and operatives; the outfit provided for them is unsuitable and inadequate. Nicolò Erizzo, Provveditor Extraordinary to the Islands of the Levant, concludes a despatch, dated October 30, 1764, as follows: “Thus it comes about that your Excellencies have no efficient and capable officers of marine, and if an occasion were ever to arise when it were necessary to send them to some distant part, let me not be deemed presumptuous if I venture frankly to assure you that they would be in great straits. I had a proof of the truth of this when I launched the galley recently built; for the officers themselves begged me to put a ship’s captain on board, since at a little distance from land they did not trust themselves, nor did they blush to confess it in making this request.”

It was ten years earlier, in 1744, that the Ridotto, or great public gaming-house, was closed in Venice by order of the Great Council, and the Venetians, their chief occupation gone, were reduced to melancholy peregrination of the Piazza. “They have all become hypochondriacs,” writes Madame Sara Gondar. “The Jews are as yellow as melons; the mask-sellers are dying of starvation; and wrinkles are growing on the hands of many a poor old nobleman who has been in the habit of dealing cards ten hours a day. Vice is absolutely necessary to the activity of a state.” This then is the Venice against which Goldoni stands out; and after all, the essential difference between the world reflected in his comedies and that world of Gentile Bellini and Carpaccio, which was Colleoni’s world, is a difference of horizon. There is an epic grandeur about Carpaccio’s world: heroes stride across it, with lesser men and lesser interests in their train. The small affairs of life are not neglected. There is the Company of the Stocking, who discuss their peculiar device and the articles of their order with the grave elaboration of State councillors. Venice was always interested in matters of detail. But in Colleoni’s day the same seriousness of purpose was available when larger issues were discerned: in Goldoni’s the power to discern larger issues has disappeared. The Venetians, lords once of the sea, can still take interest in their stockings, but they can take interest in nothing else. The Lilliputians are in possession. Goldoni does not quarrel with his age for not being monumental, and we shall do well to follow his example and make our peace with it. He looks upon the clubs of freemasons, the pedantic literary reformers, the false romanticists, the bourgeois tyrants and masquerading ladies, with a serene and indulgent smile. In his famous literary dispute with Gozzi he maintains before his fiery opponent the calm and level countenance of truth. The battles rage around him, but he stands firm and unassailable,