Chapter Six

VENICE OF CRUSADE AND PILGRIMAGE

THE story of Venice and the Crusades forms one of the most interesting pages of her history in relation to the East. The gradual awakening of her consciousness to the fact that the pilgrimages to the Holy Land might be of close significance to herself culminates in her attitude towards the great Fourth Crusade at the opening of the thirteenth century. The Crusades were, in fact, a commercial speculation for Venice, but a speculation into which she infused all the vitality and fulness of her nature. And she became, not merely a place of passage for the East, but a superb depository of relics to detain pilgrims on their outward way; a hostel so royally fitted with food for their senses, their religious cravings and their mystic imaginings, that one and another may well have been beguiled into delaying their departure for more strenuous sanctities. The narratives of the pilgrims, with their enthusiasms, their details of relics, their records of Venetian ceremonies, religious, commercial or domestic, coloured by their quaintly intimate personal impressions, form one of the most picturesque pages of Venetian chronicle.

Pietro Casola, a Milanese pilgrim of the late fifteenth century, gives us a picture of a city that is sumptuous and rich in all its dealings, yet pervaded by a harmony and decorum that has stamped itself on the face of each individual citizen. We feel that Pietro Casola has really had a vision of the meaning of Venice, when, among the inventory of wonders of the Mass for the pilgrims on Corpus Christi day, of the velvets, crimson and damask and scarlet, the cloth of gold and togas sweeping the ground, each finer than the last, he pauses to add, “There was great silence, greater than is ever observed at such festivals, even in the gathering of so many Venetian gentlemen, so that you could hear everything. And it seemed to me that everything was ruled by one alone, who was obeyed by each man without resistance. And at this I wondered greatly, for never had I seen so great obedience at such spectacles.” In the record of this arresting impression, more even than in the description of many coloured drapery and white cloths spread on the piazza, of the groves of oak-trees bordering the route of the procession and the candles lit among them, we seem to see before us the rhythmic solemnity of that unique Procession on the Piazza of Gentile Bellini. We need only Casola’s other observant characterisation of the Venetian gentleman to complete the picture. “I have considered,” he says, “the quality of these Venetian gentlemen, who for the most part are fair men and tall, astute and most subtle in their dealings; and you must needs, if you would treat with them, keep your eyes and ears open. They are proud; I think it is on account of their great rule. And when a son is born to a Venetian, they say among themselves, ‘A Signor is born into the world.’ In their way of living at home they are sparing and very modest; outside they are very liberal. The city of Venice retains its old manner of dress, and they never change it; that is to say, they wear a long garment of whatever colour they choose. No one ever goes out by day without his toga, and for the most part a black one, and they have carried this custom to such a point that all nations of the world who are lodging here in Venice, from the greatest to the least, observe this style, beginning from the gentlemen to the mariners and galleymen; a dress certainly full of confidence and gravity. They look like doctors of law, and if any were to appear outside his house without his toga he would be thought a fool.” Without doors the women also belonged to this sober company, or at least the marriageable maidens and those who were no longer of the number of the “belle giovani”; so sombrely were they covered when outside their houses, and especially in church, that Casola says he at first mistook them all for widows, or nuns of the Benedictine Order. But for the “belle giovani” it is another matter; they give relief to the week-day sobriety of these Venetians, so decorous and black when off duty, though revelling in such richness of velvet and brocade when the trumpet of a public function stirs their blood.

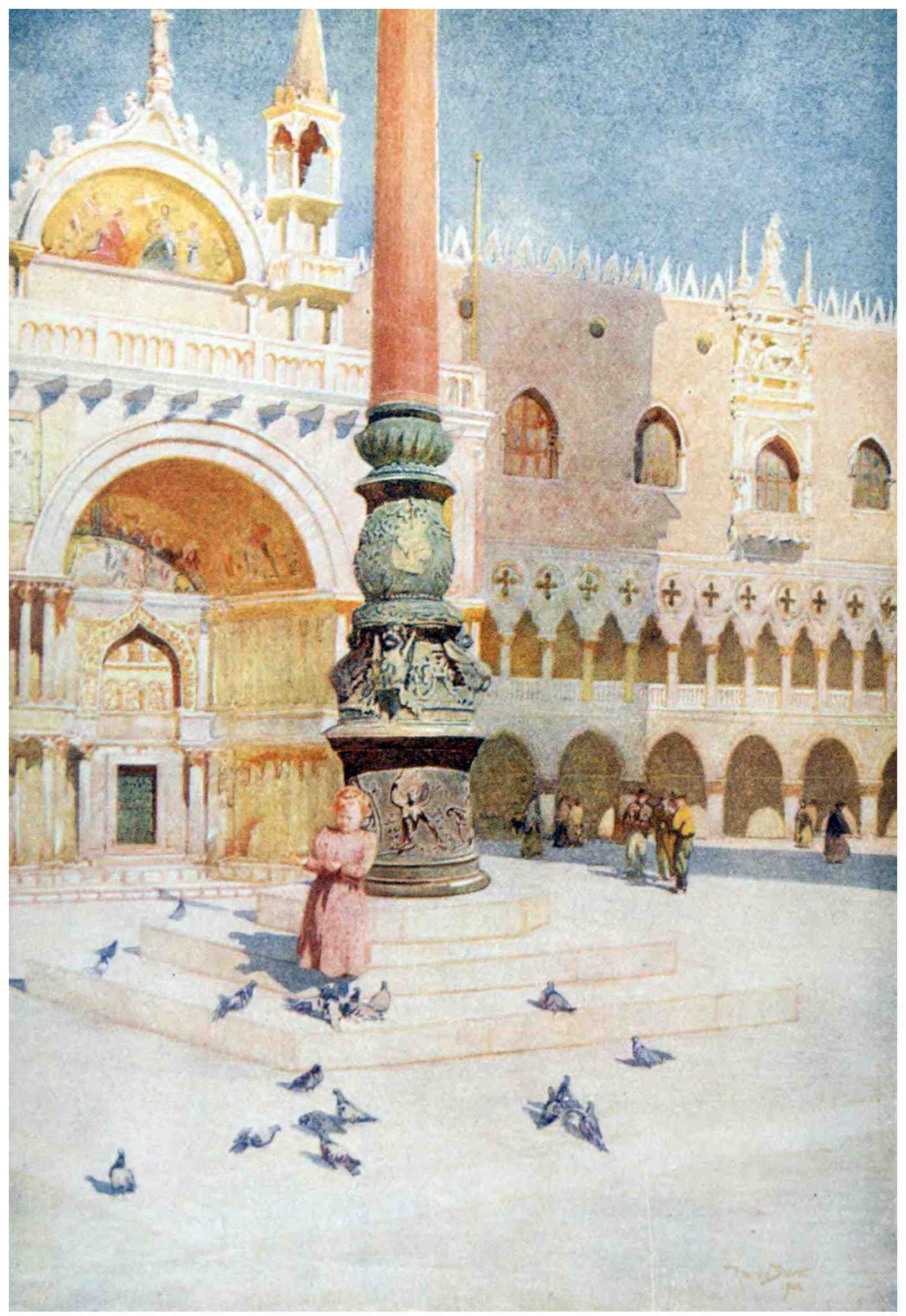

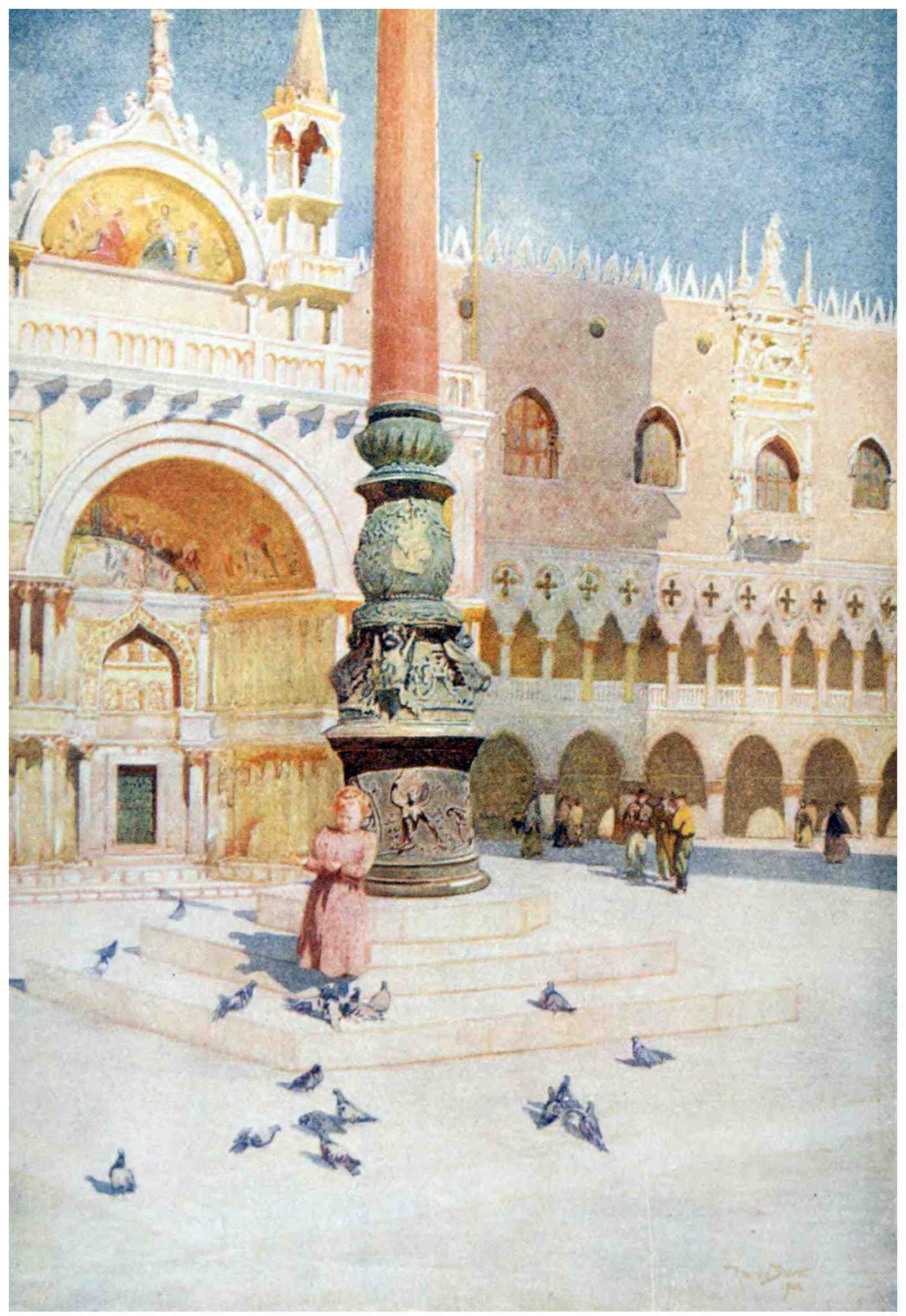

THE SHADOW OF THE CAMPANILE.

We are indebted to Casola for a picture of a Venetian domestic festival at the birth of a child to the Delfini family. He realised fully that he was admitted, together with the orator of the King of France, in order that he might act as reporter of Venetian magnificence. It was in a room “whose chimney-piece was all of Carrara marble shining as gold, so subtly worked with figures and leaves, that Praxiteles and Pheidias could not have exceeded it. The ceiling of the room was so finely decorated with gold and ultramarine, and the walls so richly worked, that I cannot make report of it. One desk alone was valued at five hundred ducats, and the fixtures of the room were in the Venetian style, such beautiful and natural figures, so much gold everywhere, that I know not if in the time of Solomon, who was King of the Jews, when silver was reputed more vile than carrion, there was such abundance as was here seen. Of the ornaments of the bed and of the lady ... I have thought best rather to keep silence than to speak for fear I should not be believed. Another thing I will speak the truth about, and perhaps I shall not be believed—a matter in which the ducal orator would not let me lie. There were in the said room twenty-five Venetian damsels, each one fairer than the last, who were come to visit the lady who had borne a child. Their dress was most discreet, as I said above, alla veneziana: they showed no more than four to six finger breadths of bare neck below their shoulders back and front. These damsels had so many jewels on their heads and round their necks and on their hands—namely, gold, precious stones and pearls—that it was the opinion of those who were there that they were worth a hundred thousand ducats. Their faces were superbly painted, and so also the rest of them that was bare.” The account of this sumptuous interior is peculiarly valuable when we realise the date to which it belongs, the period of the first greatness of Venetian Art, a period which has been sometimes regarded as one of almost naïve simplicity. Casola, with his customary exactitude, dwells on the frugality of Venetian gentlemen in the matter of food—a frugality that caused the guest to reflect that the Venetians cared more to feed the eye than the palate. It was not yet the period of the sumptuous living deplored by Calmo only half a century later.

Casola was a more secularly minded pilgrim than the priest of Florence, Ser Michele, who paid five visits to the bones of the Holy Innocents at Murano, and only at the fifth visit was counted worthy, as he humbly deemed, to see the relics: Providence, in the form of the sacristan, having till then failed him. The more festive Casola—who paid repeated visits to Rialto, “which seemed to be the source of all the gardens in the world,” who spent one day in vain attempts to count the multitudinous boats in and about the city, and who was so frivolous, for all his long white beard, as to buy a false front on the piazza—in the midst of his expatiations on the Venetian maidens, pulls himself suddenly together with a sense of incongruity between his diversions and his goal, and shakes himself free from the allurements of Venice, crying: “But I am a priest, in the way of the saints; I did not try to look into their lives any further. To me it seemed better, as I have said above, to go in search of the churches and monasteries and to see the relics of which there are so many. And this seemed to me a good work for a pilgrim who was awaiting the departure of the vessel to go to the Holy Sepulchre, bringing the time to an end as well as he could.” In the Accademia at Venice there is a curious little painting, attributed to Carpaccio, of the assembly of the martyrs of Mount Ararat in the Church of Sant’ Antonio di Castello, which stood once on the site of the Public Gardens. It was a familiar sight for Venice, the dedication of pilgrims that is represented here; and there is a strange pathos in the slim, small figures as they move in two lines half-wavering up the aisle, each wearing a crown of thorns, perhaps in prophecy of coming martyrdom. They are not marching confidently to victory like an army; their crosses are held at all angles, forming errant patterns among themselves. Some are girt for their journey in short vestments under their long robes. It is curiously unlike a procession native to the city; there is a dreamlike, mystic quality about it and a lack of body in its motion which is enhanced, perhaps, by the extreme detail with which the interior of the church is transcribed—the models of vessels in the rafters; the votive limbs and bones hung on the wooden screen, offerings of the diseased cured by miracle, as they may be seen in San Giovanni e Paolo to-day; the coiled rope of the lamp-pulley; the board with a church notice printed on it; and everywhere, winding in and out of the picture, seen through the portal of entrance, disappearing behind the sanctuary screen, the interminable procession of the ten thousand little pilgrims.

In 1198 the lords of France flocked with enthusiasm to a crusade preached by Foulques de Nuilly under the authority of Innocent III. After much discussion of practical ways and means, with which they were less amply provided than with spiritual enthusiasm, they made choice of six ambassadors who should procure the necessities of the enterprise, Jofroi de Villeharduin, Mareschal of Champagne, Miles li Brabant, Coëns de Bethune, Alars Magnarians, Jean de Friaise, and Gautiers de Gaudonville. Venice was decided on by them as the State most likely to provide what they stood in need of—ships for the journey—and they departed to sound the mind of the Republic, arriving in the first week of Lent in the year 1201. Venice, in the person of the Doge, Henry Dandolo, opened the negotiations; the messengers were made to feel it was no light thing they asked. They were received and lodged with highest honour, but they were made to wait for a Council to assemble, which should consider the matter of their request. After some days they were admitted to the Ducal Palace to deliver their message; and its purport was this: “Sir, we are come to you from the high barons of France who have taken the sign of the Cross to avenge the shame of Jesus Christ, and to conquer Jerusalem if God will grant it them; and because they know that no people have such power as you and your people, they pray you for God’s sake to have pity on the land over seas and the avenging of the shame of Jesus Christ, so that they may have ships and the other things necessary.” The spiritual and sentimental appeal is left unanswered by the Doge. He asks simply, “In what way?” “In all ways,” say the messengers, “that you recommend or advise, which they would be able to fulfil.” Again the Doge expresses wonder at the magnitude of what they ask, bidding them not marvel if another eight days’ waiting is required of them before the final answer can be given. At the date fixed by the Doge they returned to the Palace. Villeharduin excuses himself from telling all the words that were said and unsaid, but the gist of the Doge’s offer was this, that it depended on the consent of the Great Council and the rest of the Republic. Venice should provide vessels of transport for four thousand five hundred horses and squires and twenty thousand foot soldiers, and viands to last the whole company nine months. The agreement was to hold good for a year from the time of starting, and the sum total of the provision was to be eighty-five thousand marks. But Venice would go further, for the love of God, and launch fifty galleys at her own expense on condition of receiving the half of all the conquests that were made by land and sea. Nothing remained but to win the consent of the Great Council and ask a formal ratification from the people. Full ten thousand persons assemble in “the chapel of San Marco, the fairest that ever was,” and the Doge recommends them to hear the Mass, and to pray God’s counsel concerning the request of the envoys. It will be seen that all is practically accomplished before the question is put to the people or God’s grace asked on the undertaking, but no item of the formality is omitted. The envoys are sent for by the Doge that they may themselves repeat their request humbly before the people, and they came into the church “much stared at by the crowd who had never seen them.” Again the appeal is made, Jofroi de Villeharduin taking up the word by the agreement and desire of the other envoys. We can picture the strange thrill that ran through the great multitude as that single voice broke the silence of St. Mark’s with its burden of passionate tribute to the greatness of Venice: “‘Therefore have they chosen you because they know that no people accustomed to going on the seas have such power as you and your people; and they commanded us to throw ourselves at your feet and not to rise until you had consented to have pity on the Holy Land beyond the seas.’ Now the six messengers knelt, weeping bitterly, and the Doge and all the others cried out with one voice and raised their hands on high and said, ‘We grant it, we grant it.’ And the noise and tumult and lament of it were so great that never had any man known a greater.” Then the Doge himself mounted the lectern and put before the people the meaning of the alliance that had been sought with them in preference to all other peoples by “the best men of the world.” “I cannot tell you,” says Villeharduin, “all the good and fair words that the Doge spoke. At last the matter was ended, and the following day the charters were drawn up and made and sealed.”

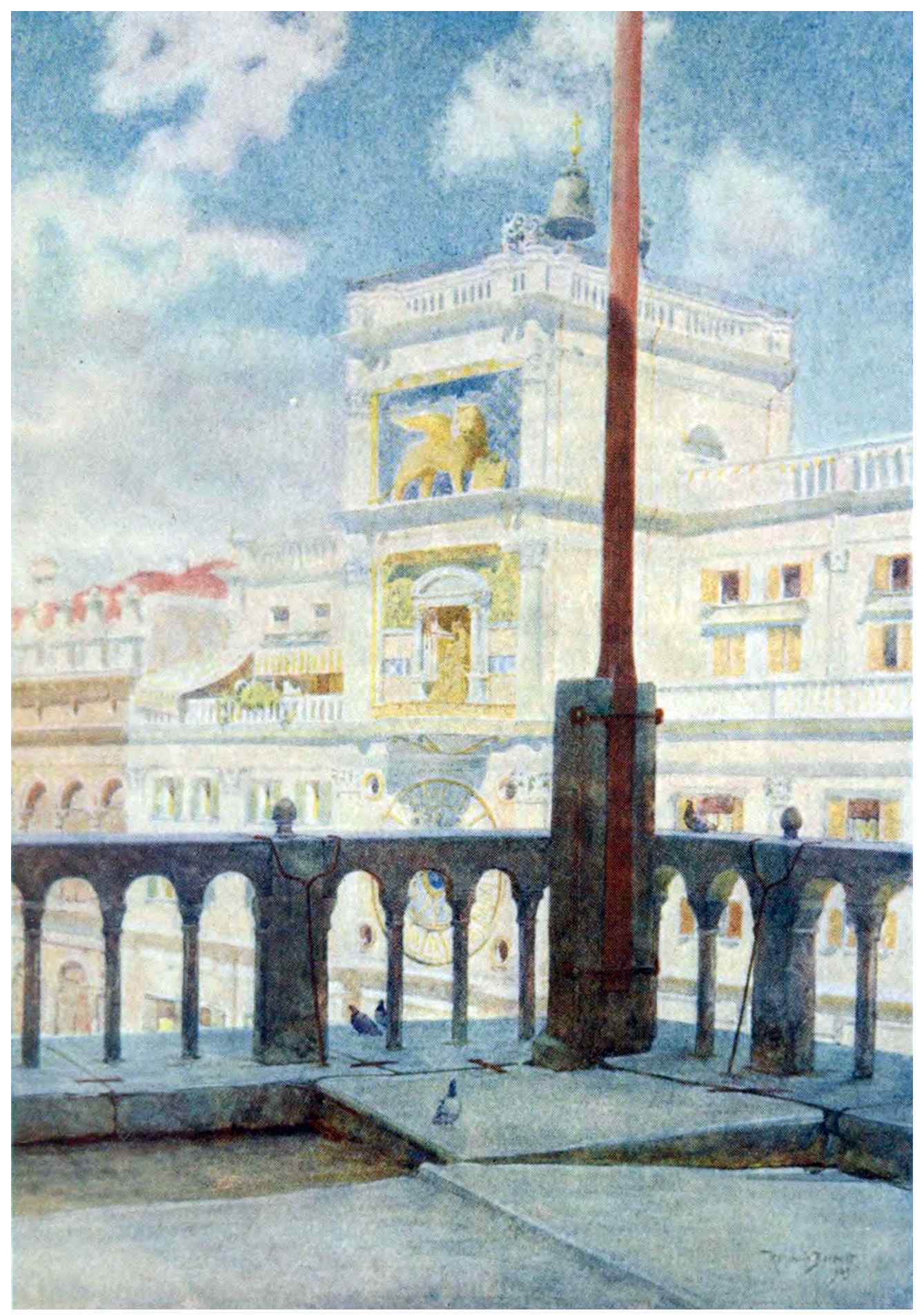

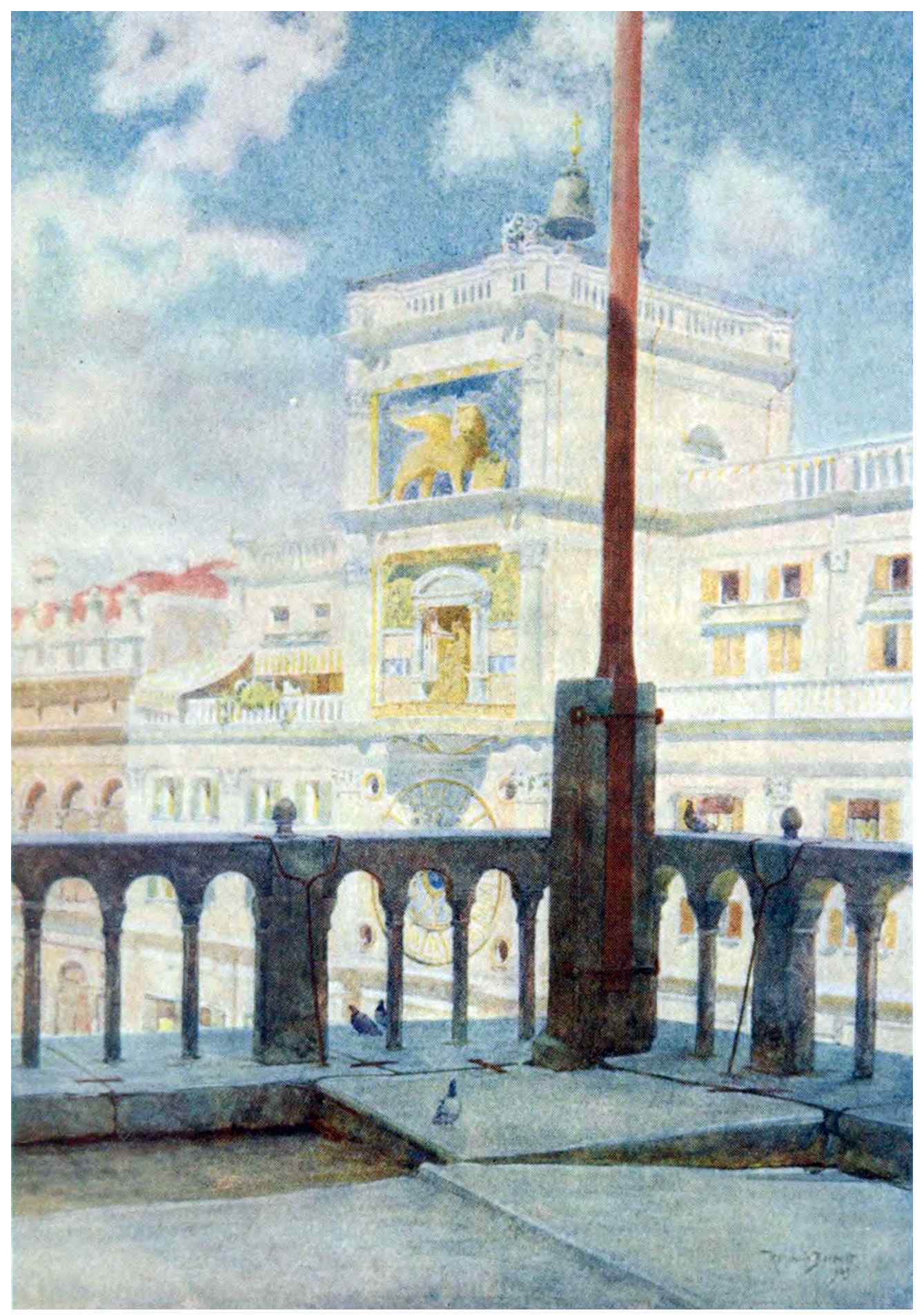

THE CLOCK TOWER FROM GALLERY OF SAN MARCO.

The time of gathering for the pilgrims was fixed for the following year 1202, at the feast of St. John, and amid many tears of piety and devotion the Doge and deputies swore to abide by their charters, and the envoys of both parties set out for Rome to receive the confirmation of their covenant from Innocent III. But the drama which had begun amid such moving demonstrations of good will and Christian sentiment necessarily had its dilemmas and its complications. It was essential to the fulfilling of the pact that all the crusaders should assemble at Venice to pay their toll, and embark on the ships; otherwise the crusaders could not hope to provide the money due to the Venetians. The Republic, for its part, had amply fulfilled its compact. All who arrived were received with joy and lodged most honourably at San Nicolo del Lido. The chronicle can find no parallel for the richness of the provision made for the would-be crusaders. But there were, alas, three times as many vessels as there were men and horses to fill them.—“Ha! it was a great shame,” bursts out Villeharduin, “that the rest who went to the other ports did not come here.” The dilemma was a serious one. Even of those who were there, some declared themselves unable to pay their passage, and the money could in no way be made up. Some were for sacrificing their whole estate that the Venetians should not lose by the defection of the others, but the counsel found small support among those who now wished to be rid of their bargain. But the small party who felt themselves, in a sense, the conscience of the Crusade carried the day. “Rather will we give all we possess and go poor among the host, than that it should disperse and come to naught; for God will render it to us at His good pleasure.” So the Counts of Flanders, Loys, Hues de St. Pol and their party began to collect together all their goods and all they could borrow. “Then you might have seen a vast quantity of gold and silver borne to the palace of the Doge to make payment. And when they had paid, there still was lacking from the covenant thirty-four thousand marks of silver. And those who had kept back what they possessed and would give nothing were very glad at this, for by this means they thought the expedition would have failed. But God who counsels the disconsolate would not so suffer it.” The Doge put before his people that not only would their just claim remain unsatisfied though they should exact from the crusaders the utmost they could collect, but they would bring discredit on themselves by acting as strict justice would permit. He suggested the combining of two advantages, a material and moral. Let them, he suggests, demand the reconquest of Zara as substitute for the debt, that they may not only have the fame of possessing the city but the praise of generosity. And Dandolo, the old wise doughty Doge, has yet another suggestion to propose. There was a great festival one Sunday in San Marco, and the citizens and barons and pilgrims were assembled before High Mass began. Then amid the silent expectation of the great gathering the Doge mounted the lectern and made the famous offer of his own person as leader of the host. “‘I am an old man,’ he said, ‘and feeble, and should be feeling need of repose, for I am infirm in body. But I see there is none who could so well rule and lead you as I who am your lord. If you will consent that I take the sign of the Cross to preserve and guide you, and that my son remain in my stead and keep the city, I would gladly go to live and die with you and with the pilgrims.’ And when they heard, they cried all with one voice: ‘We pray you for God’s sake to grant us this, and to do so and to come with us.’ And the people of the city and the pilgrims, felt deep compassion at this, and they wept many tears, thinking how that valiant man had so much need to stay behind, for he was an old man, and though his eyes were still fair to look on he could not see with them on account of a wound which he had received in his head. Nevertheless he had a great heart. Ha! how little they resembled him who had gone to other ports to avoid danger! So he came from the pulpit and went to the altar and knelt down, weeping bitterly, and they sewed the cross for him on a great cotton cap because he desired that the people might see it. And the Venetians began to take the cross in great numbers, and many on that very day, and still the number of crusaders was few enough.” It was no wonder that the pilgrims had great joy in the crusaders for the good will and valour they felt to be in them. Whatever aim may previously have been uppermost as an incentive to enthusiasm and self-oblation, there was no doubt that Venice now was giving of her best. This retiring of the old Doge from his ducal throne to embark on a more arduous leadership is one of the most moving episodes in the annals San Marco.

But at this moment an event occurred that changed, or rather diverted into a new channel the current of the Crusade, providing in fact, as our chronicler Villeharduin remarks, the true occasion of his book. Into the midst of the pilgrims assembled at Verona on their way to Venice there came Alexius, son of Isaac the deposed Emperor of Constantinople, in quest of help against his usurping uncle. What more opportune than the neighbouring host of “the most valiant men on earth” for aiding in the recovery of his lost kingdom and the reinstatement of his tortured father. To the crusaders, and especially we may believe, to the Venetians, this new motive did not come amiss. It is startlingly like life, this Fourth Crusade, with its original aim thus gradually becoming but a secondary purpose in a far more complicated scheme, a middle distance in an increasingly extended horizon. The relief of the Holy Sepulchre, the avenging of the shame of Christ, assume in fact a rather shadowy outline in a prospect dominated by Zara and Constantinople.

The departure from Venice did not mark the term of the obstructions to which the Crusade was fated. The disgraceful contest between the French and the Venetians within the streets of Zara, the defection of a number of the pilgrims, the death of others at the hands of the wild inland inhabitants of Dalmatia—all these causes reduced the already meagre company before it had well started on its way. The Pope was placed in the dilemma of strongly disapproving the secular turn given to the Crusade, while realising that the Venetian fleet was the only means for accomplishing his ends in Palestine. His solution was to absolve the barons for the siege of Zara, permitting them still to use the fleet—though the devil’s instrument—while Venice, the provider, remained under interdict. We here come into contact with an element of singular interest in the relations of Venice and the East—her attitude towards the Papacy. The independence of San Marco was one of the essential articles of the Venetian creed. In spiritual matters none could more devoutly bow to the Apostle of Christendom; but the spiritual supremacy was an inland sea to Venice: it must be stable, fixed, defined; it must not flow with a tide upon the temporal shores where her heart and treasure lay. The authority of San Marco was a political principle. All state ceremonies were bound up with San Marco; the Ducal Palace itself was subsidiary to the Palace of St. Mark. How should a State that had sheltered, traditionally at least, a Pope “stando occulto propter timorem” that had acted as mediator between Pope and Emperor and seen the Emperor’s head bowed to the ground on the pavement of San Marco—how should such a State be subordinate to any rule but its own complete self-consciousness? Venice always followed the eminently practical rule of allowing much freedom in non-essentials in order to preserve more closely her control over the really material issues. The attitude always maintained by her with regard to the Inquisition is so closely parallel to her relations with the East and the pagans of the East, constantly deprecated by the Pope, that we may fitly quote here Paolo Sarpi’s admirable reply to the papal protests against conferring the doctorate in Padua on Protestants; the principle is the same, though limited in that instance to a particular and seemingly divergent issue. “If anyone openly declared his intention of conferring the doctorate on heretics, or admitted anyone to it who openly and with scandal professed himself to be such, it might be said that he had failed to persecute heresy; but, it being the opinion of the most Serene Republic that heretics and those who are known for such should not be admitted to the doctorate, and it being our duty to consider Catholic anyone who does not profess the contrary, no smallest scandal can accrue to the religion even though it should chance that one not known for such were to receive the doctorate. The doctorate in philosophy and medicine is a testimonial that the scholar is a good philosopher and physician and that he may be admitted to the practise of that art, and to say that a heretic is a good doctor does not prejudice the Catholic faith; certainly it would prejudice it if anyone were to say that such a man was a good theologian.” This was the position of Venice with regard to her pagan allies, the meaning of her superbly fitted lodges for Turk, infidel and heretic. The Saracen, the Turk and the Infidel might not be a good theologian, but he was a good trader, a channel for the glories with which Venice loved to clothe and crown herself. He was a part of her life more essentially and more irrevocably than the prelates of holy Church; his ban would have been more terrible to Venice than papal thunders. It was not primarily as hot sons of the Church, consumed with fire for the shame of the Holy Sepulchre that the Venetians with such generous provision prepared their ships for the Crusade: it was as men of business with no small strain of fire in their blood and a high sense of the glorious worth and destiny of their city.

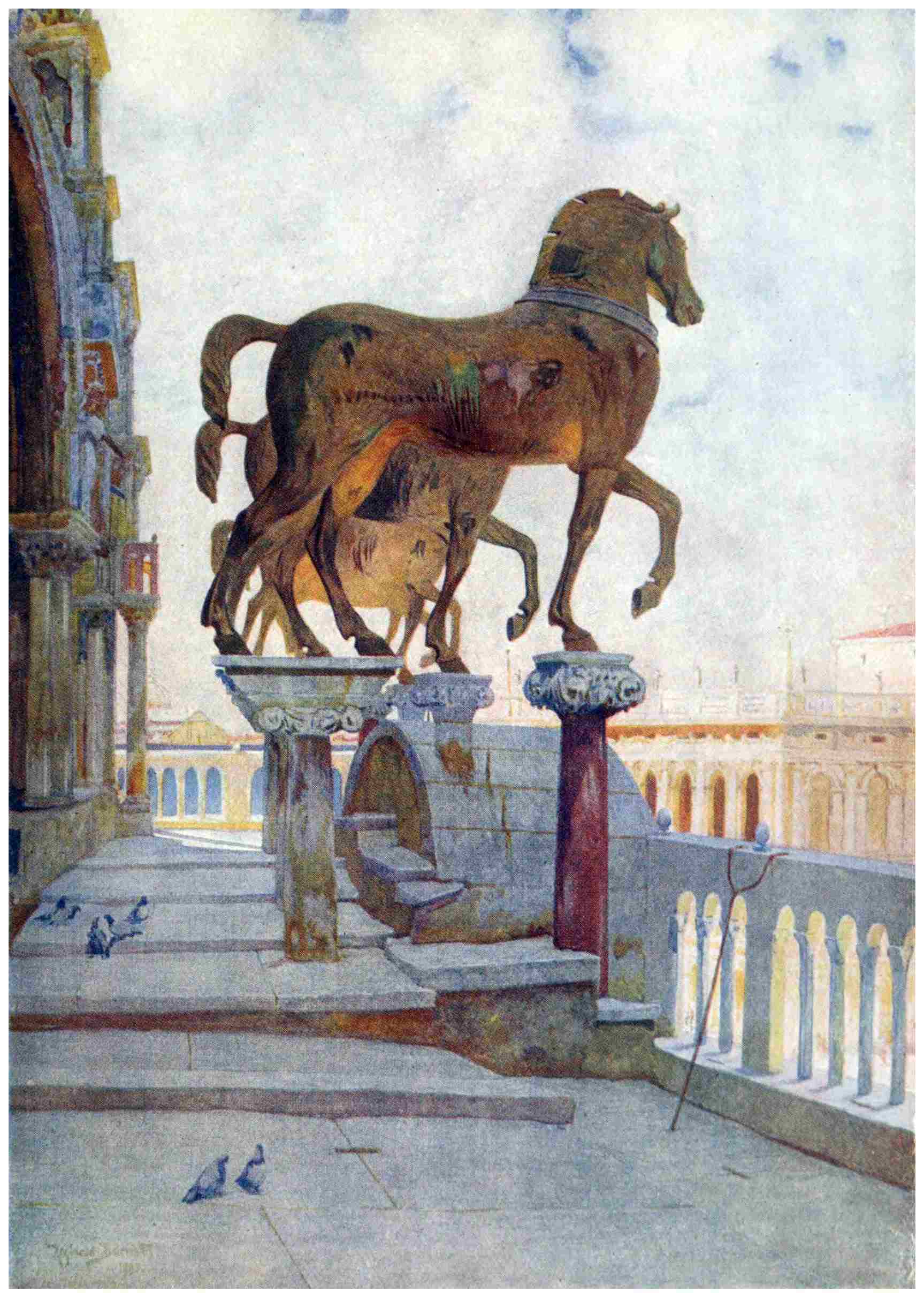

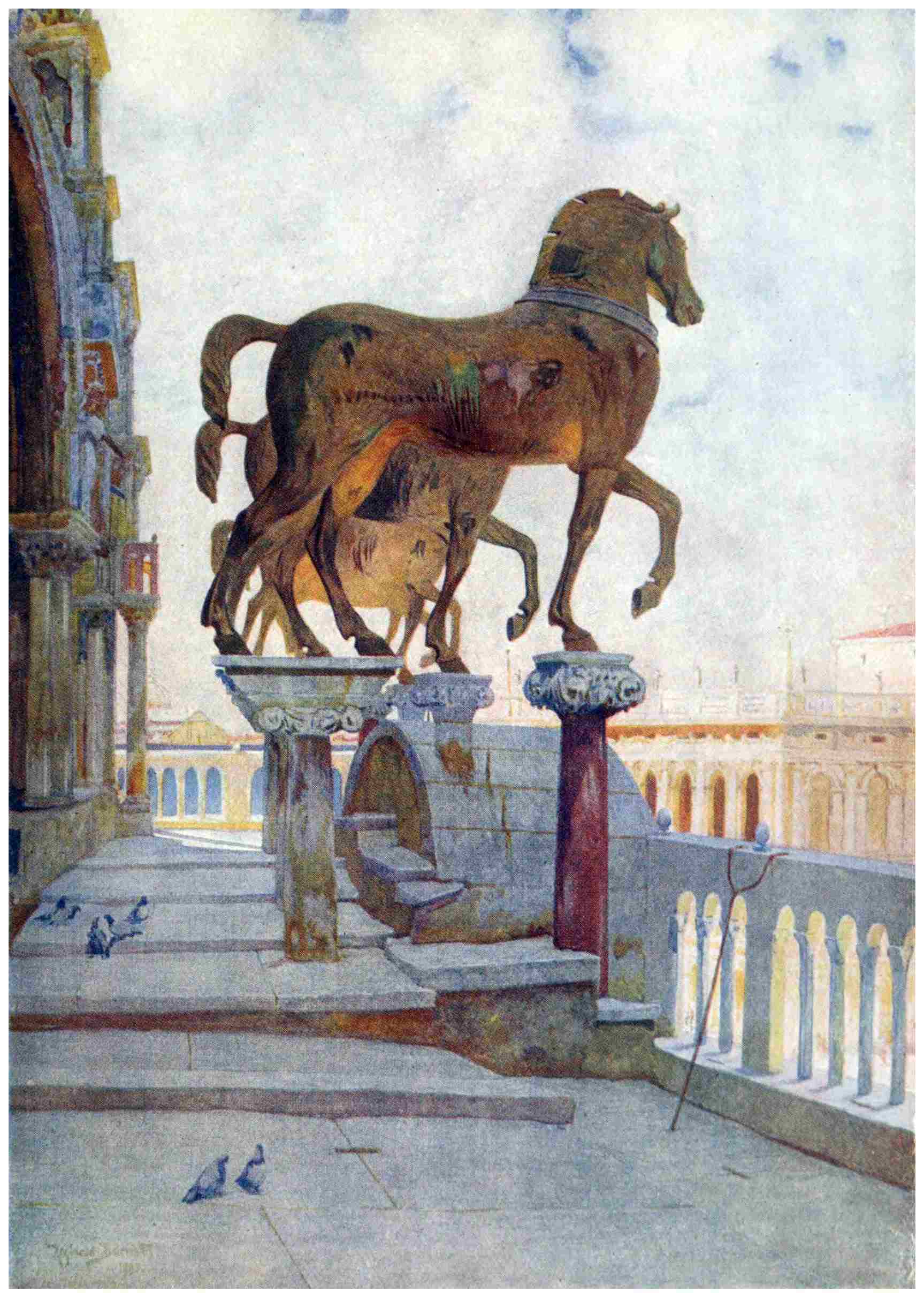

THE HORSES OF SAN MARCO, LOOKING SOUTH.

There were moments of inspiration for the Crusaders amid all their toils and internal strife, and not least was the first view of Constantinople which had been for so long the emporium of Venice. The fleet had harboured at the abbey of St. Etienne, three miles from Constantinople, and Villeharduin describes the wonder and enthusiasm of those who saw then for the first time the marvellous city “that was sovereign over all others,” with its rich towers and palaces and churches and high encircling walls. “And you must know there was no heart there so daring but trembled.” We are reminded of this picture of Constantinople when we stand face to face with Carpaccio’s city in the Combat of St. George. It so successfully combines solidity and strength with the airy joy of watch-towers and towers of pleasure, that at first we have only the impression of fantastic play of architecture; but by degrees we come to feel the seacoast country of Carpaccio, that at first seemed so wild and unmanned, to be in fact bristling with defence and preparation. It is immensely strong in fortifications, no dream or fairy citadel. It is begirt with towers and walls along the water; strongholds lurk among the loftiest crags; towers of defence and battlements peer over the steep hillside; and, if we look closer, we see the towers are thronged with men. We remember Villeharduin’s note, “There were so many men on the walls and on the towers that it seemed as if they were made of nothing but people.” It is a sumptuous city, too, that we see in glimpses through the gateway, the city of a great oriental potentate.

We cannot follow Villeharduin through the vicissitudes of the siege and counter-siege. He himself confesses in the relation of one point alone that sixty books would not be able to recount all the words that were spoken, and the counsels that were given and taken. In the simple, terse and trenchant style that Frenchmen, and especially the Frenchmen of the old chronicles, know how to wield so perfectly, he tells us of the Doge’s wise counsel that the city should be approached by way of the surrounding islands whence they might gather stores; of the lords’ neglect of this counsel, “just as if no one of them had ever heard of it”; of their investment of the palace of Alexius in the place named Chalcedony, that was “furnished with all the delights of the human body that could be imagined befitting the dwelling of a prince”; of the capture of the city and the ravishing of its treasures that were so great “that no man could come to an end of counting the silver and the gold and plate and precious stones and samite and silken cloth and dresses vaire and grey, and ermines and all precious things that were ever found on earth. And Jofroi de Villeharduin, the Marshall of Champagne, will bear good witness that to his knowledge since the centuries began there was never so great gain in a single city.” The division of the booty necessarily occasioned heart-burning and revealed certain vices of “covetoise” undreamed before. And as time went on and still the passage to Palestine was delayed the sanctuaries of the Greek Church were treated with barbarous irreverence and despoiled of their treasure and sacred vessels. Then with the retaking of Constantinople from Marzuflo there followed a time of abandonment of men and leaders to their fiercest passions and the almost total destruction of the city. Here again Venice stepped in, as the merchant had stepped in to rescue treasure from the pile of Savonarola, to enrich herself from the ruins of Constantinople.

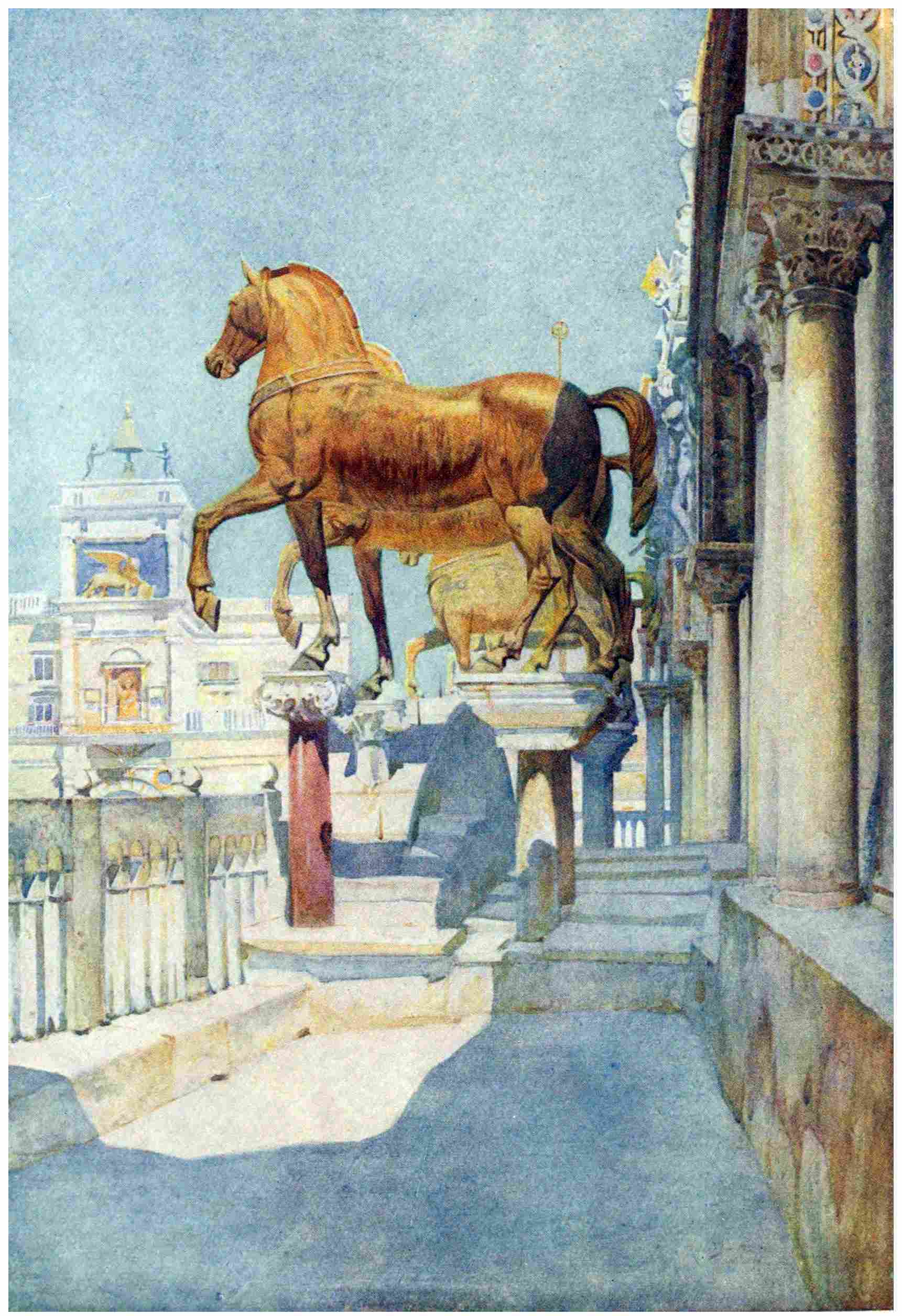

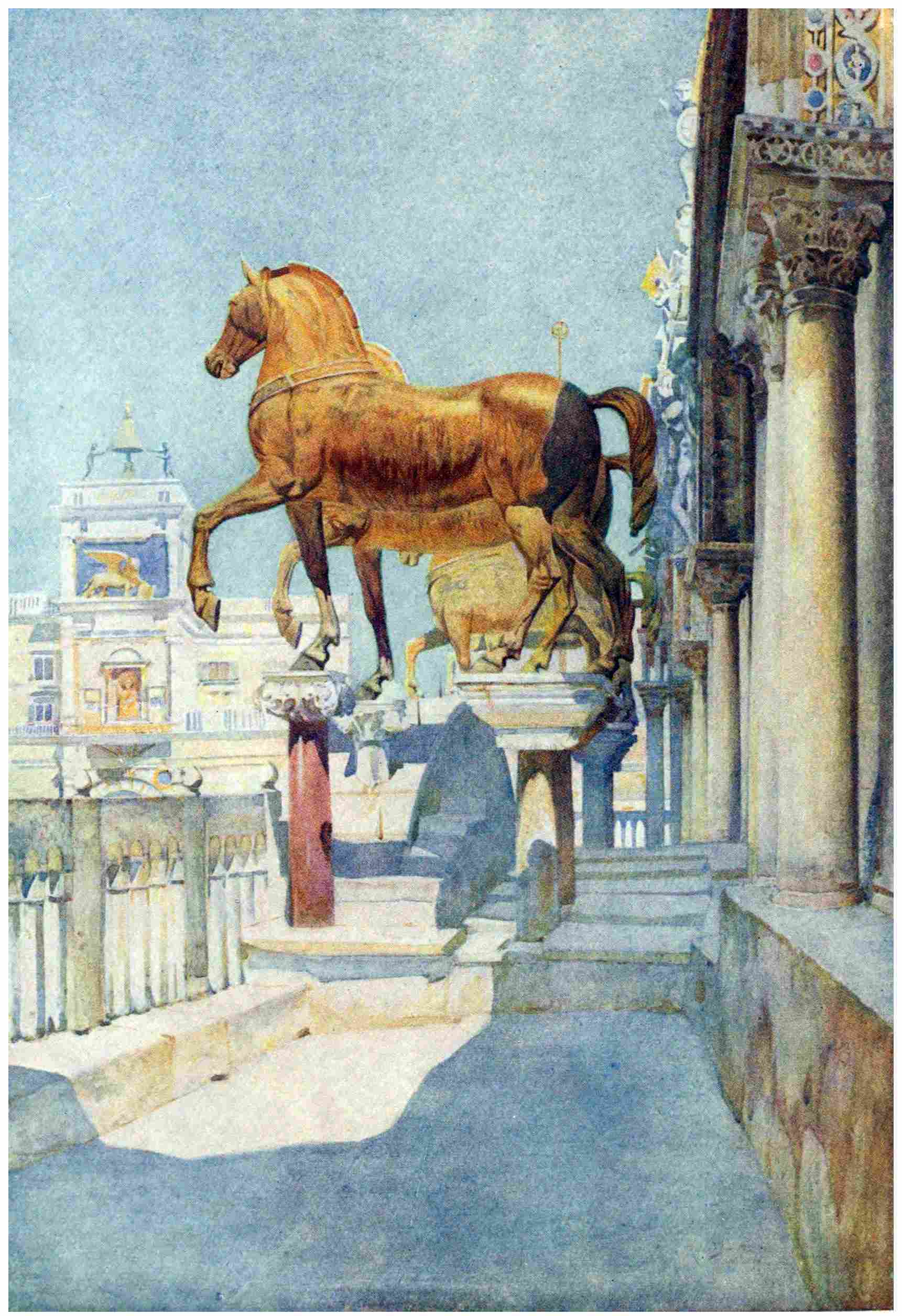

The taking of Constantinople opened another door into the Eastern garden from which Venice had already begun to gather so rich an harvest. Picture the freights that Venetian vessels were bearing home in these years of crusade and conquest, to be gathered finally into the garner of St. Mark’s! It is strangely thrilling to imagine the first welcome of the four bronze horses, travel-dimmed no doubt, who only found their way to their present station on the forefront of St. Mark’s after standing many times in peril of being melted down in the Arsenal where they first were stored. But at last, says Sansovino, their beauty was recognised and they were placed on the church. It is only by degrees that we come to accost and know the exiles one by one. The more outstanding spoils, the Pala d’Oro, the great pillars of Acri, the bronze doors, the horses, the four embracing kings, these are among the first letters of St. Mark’s oriental alphabet; but there are many lesser exiles which have found a shelter in the port of Venice, which as we wander among the glorious precincts of San Marco impress themselves upon us one by one; such is the grave-browed, noble head of porphyry that keeps solitary watch towards the waters from the south corner of the outer gallery of San Marco, as if it had been set down a moment by its sculptor and forgotten on the white, marble balustrade. The whole being of San Marco is bound up with the East, and it is another token of the magic of Venice that she has been able to embrace and furnish with a life-giving soil those plants that had been ruthlessly uprooted and had made so long and perilous a journey. The official records, that tell of the arrival from one expedition and another of Eastern vestures for the clothing of San Marco, are not mere inventories to us who have walked upon the variegated pavement between the solemn pillars and seen the sunlight illumine one by one the marbles of the walls, with their imbedded sculpture and mosaic, or gild the depths of the storied cupolas and the luxuriant harmonies of colour and design on the recesses of the windows. They are significant, these records, like the entry in a parish register of the birth of some one whom we love; for the church of San Marco, though in fact a museum of many treasures, is not a museum of foreign treasures. Her spoils are not hung up in her as aliens like the spoils that conquerors bore to ancient temples; they found her a foster-mother of their own blood and kin. She herself is sprung from a plant whose first flowering was not among the floating marshes of the lagoon.

By permission of the Hon. John Collier.

THE HORSES OF SAN MARCO, LOOKING NORTH.

Turn, on a sunny day, from the Molo towards San Marco, passing below the portico of the Ducal Palace adjoining the Piazzetta. Framed by the pointed arch at the end is a portion of the wall which once formed the west tower of the Ducal Palace. This delicate harmony of coloured marbles and sculptured stone seems a rare and beautiful creation, not of stone but of something more plastic, more mobile, so responsive is it to the light, so luminous, so full of feeling. As we draw nearer and it becomes more clearly defined, we see great slabs of marble sawn and spread open like the pages of a book, corresponding in pattern as the veining of a leaf. They are linked by marble rope-work, and between them are inserted smaller slabs of delicately sculptured stone and a wonderful coil of mosaic. It is a veritable patchwork wall, but no less beautiful in its effect of harmony than in its details—the four porphyry figures of embracing kings its corner-stone. This wall is truly a key to the fabric of the church itself; it is like a window into St