Chapter Three

THE NUPTIALS OF VENICE

UNTIL the fall of the Venetian Republic the rite of the Sporalizio del Mare, the wedding of Venice with the sea, continued to be celebrated annually at the feast of the Ascension. Long after the fruits of the espousal had been gathered, when its renewal had become no more than a ceremonious display, there stirred a pulse of present life in the embrace; and in a sense, the significance of the ceremony never can be lost while one stone remains upon another in the city of the sea.

For the earliest celebration of the nuptials there was need of no golden Bucintoro, no feast of red wine and chestnuts, no damask roses in a silver cup, not so much as a ring to seal the bond. For it was no vaunt of sovereignty; it was a humble oblation, a prayer to the Creator that His creature might be calm and tranquil to all who travelled over it, an oblation to the creature that it might be pleased to assist the gracious and pacific work of its Creator. The regal ceremony of later times was inaugurated by the Doge Pietro Orseolo II who, having largely increased the sea dominion of Venice and made himself lord of the Adriatic, welded his achievement into the fabric of the state by the ceremony of the espousal. The ring was not introduced till the year 1177, when Pope Alexander III, being present at the festival, bestowed it on the Doge, as token of the papal sanction of the ceremony, with the words, “Receive it as pledge of the sovereignty that you and your successors shall maintain over the sea.” But the true importance of the festival, whether in its primitive form or in its later elaboration, is the development of Venetian policy which it signified—a development which, for the purposes of this chapter, will best be considered in relation to events separated by nearly two centuries, but united in their acknowledgment of the growing importance of Venice on the waters. The first is Pietro Orseolo’s Dalmatian campaign, followed in 1001 by the secret visit of the German Emperor Otho III, and the second the famous concordat of Pope Alexander III and the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, concluded under the auspices of Venetian statecraft in 1177.

Pietro Orseolo II appears as one of the most potent interpreters of the Venetian spirit. He combined qualities which enabled him to gather together the threads which the genius of Venice and the exigencies of her position were weaving, and to fashion from them a substantial web on which her industry might operate. He was a soldier, a great statesman and a patriot. All the subtlety, all the ambition, all the dreams of glory with which his potent and spacious mind was endowed, were at his country’s service, and the material in which he had to work was plastic to his touch. Venice lay midway between the kingdoms of the East and West, and from the earliest times this fact had determined her importance: she might rise to greatness or she might be annihilated; she could not be ignored. The Venice of Orseolo was instinct with vitality and teeming with energies, but she was divided against herself. The foundations of her greatness were already laid, but her general aim and tendency were not determined. She was in need of a leader of commanding mind and capacious imagination, who could envisage her future, and who should possess the power of inspiring others with confidence in his dreams. Such a man was Pietro Orseolo II. Venice had been threatened with destruction by the division of the two interests which, interwoven, were the basis of her power. Before the final settlement at Rialto she had been torn hither and thither by the factions of the East and West, the party favouring Constantinople and the party favouring the Frankish King; and at any moment still the Doge’s policy might be wrecked by the rivalries of the two parties, if he proved lacking in insight or capacity for uniting in his service the interests of both.

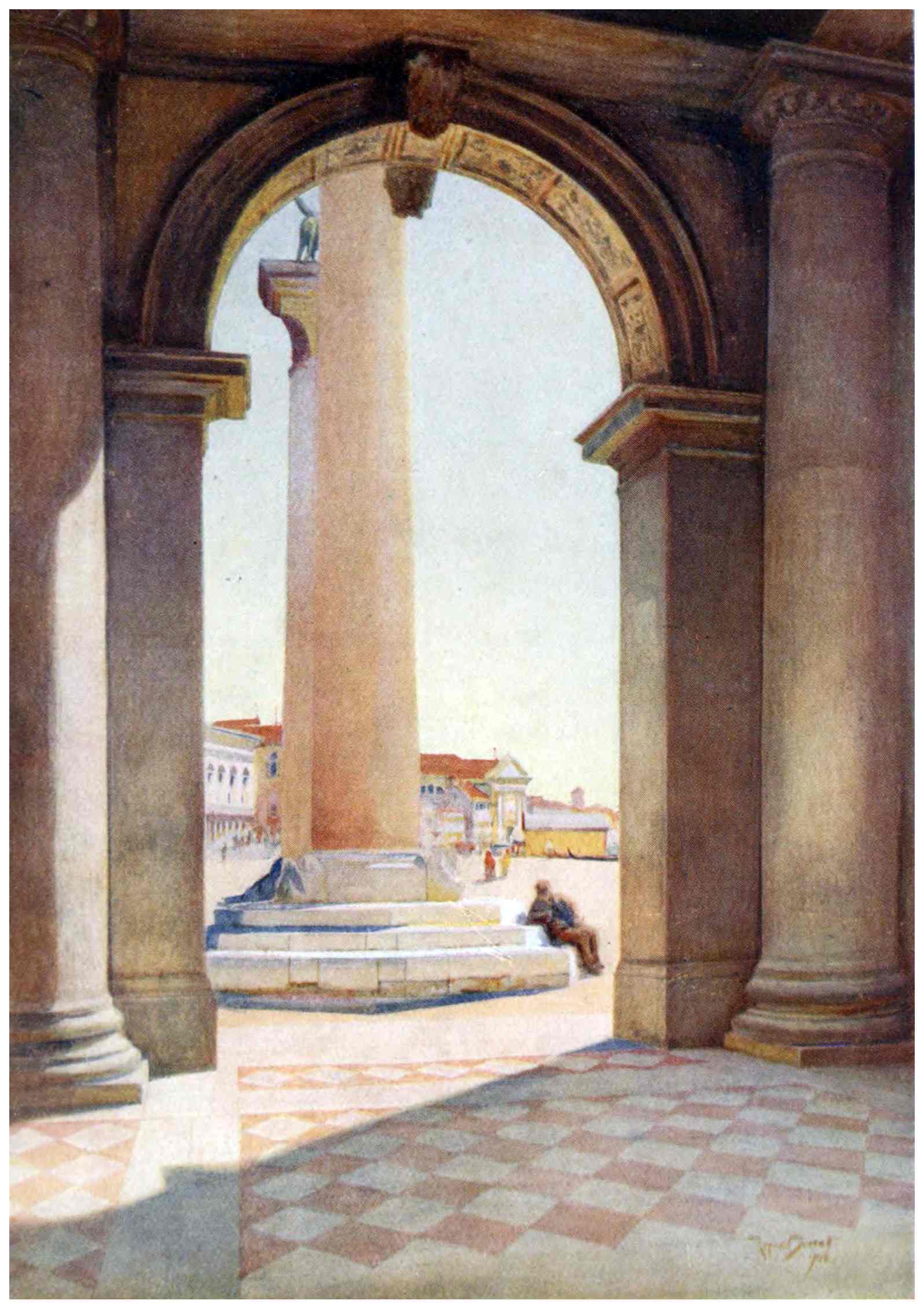

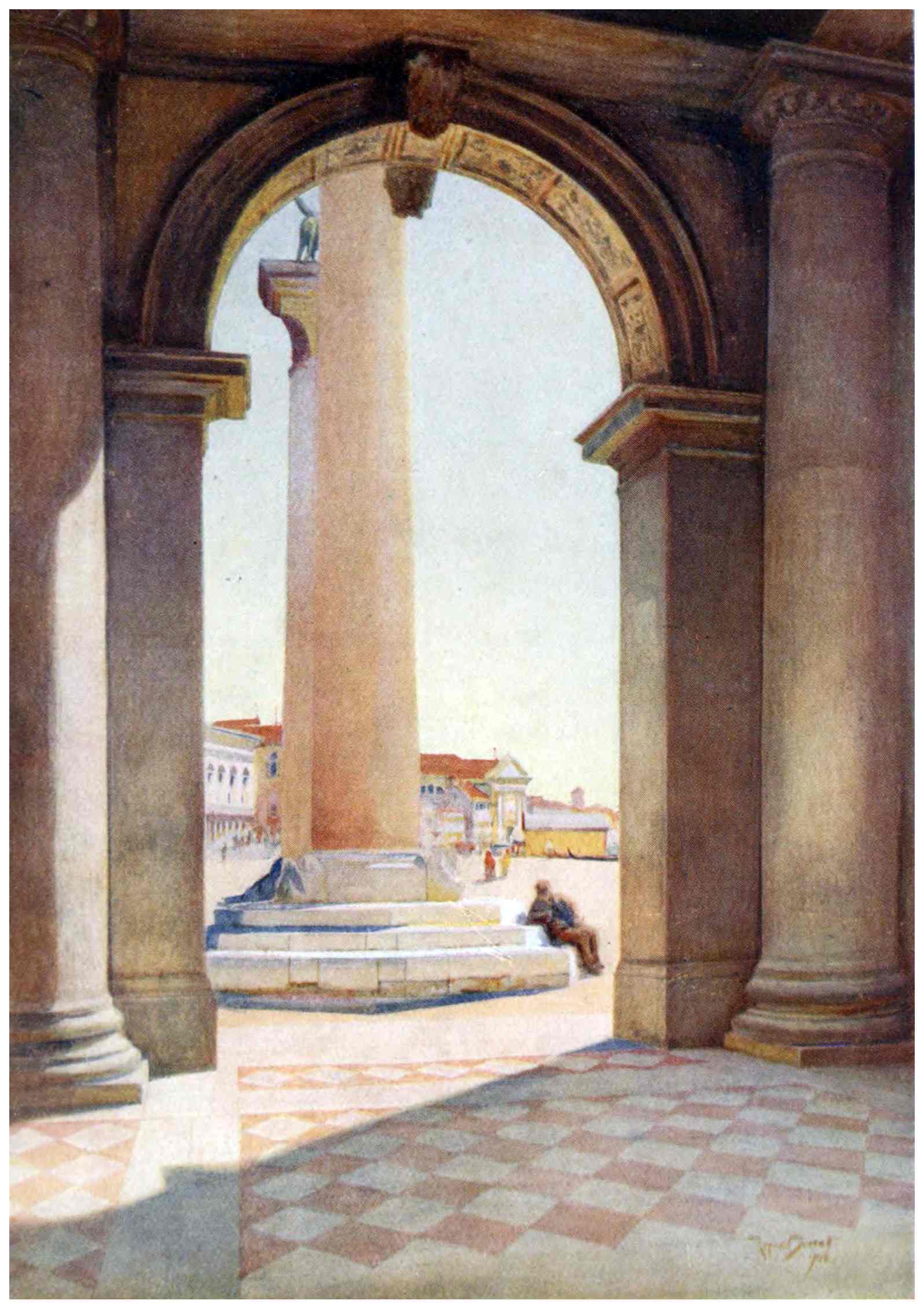

RIVA DEGLI SCHIAVONI.

For some time Dalmatia had been a thorn in the side of Venice, a refuge for the disloyal, and, through the agency of the hordes of pirates infesting the coast, a real menace to her commerce. Venice had attempted to purchase immunity from the pirates by payment of an annual indemnity. Orseolo decided at once to put an end to this payment, but he realised that the price of the decision was a foothold in Dalmatia that would need to be obtained by force of arms. For this end it was necessary to secure harmony within the city itself, and, knowing this, he exercised his powers to obtain approval of his expedition from the authorities of East and of West, from the Emperors of Germany and Byzantium. He was successful in this, and circumstances combined further to aid his designs. The Croatians and Narentines, by wreaking on Northern Dalmatia their anger at the loss of the Venetian indemnity, had prepared the minds of the Dalmatians to look on the prospect of Venetian supremacy as one of release rather than of subjugation. It is said that they even went so far as to send a message to Orseolo encouraging his coming. Their province was nominally under the Emperor of Byzantium, but their overlord had decided to look favourably on a means of securing peace and safe passage to his province at so small an expense to himself. Orseolo set sail on Ascension Day, after a service in the Cathedral of Olivolo (now San Pietro di Castello), fortified by the good will of East and of West, and the united acclamations of all parties in Venice. Pride and vigorous hope must have swelled the hearts of these warriors. It was summer, and their songs must have travelled across the dazzling blue of the great basin of St. Mark, and echoed and re-echoed far out on the crystal waters of the lagoon. Triumph was anticipated, and triumph was their portion. Orseolo’s expedition was little less than a triumphal progress; the coast towns of Dalmatia from Zara to Ragusa rendered him their homage. A new and immensely rich province was acquired by Venice, and the title of Duke of Dalmatia accorded to himself.

Soon after Orseolo’s return from this campaign, Venice, unknown to herself, was to receive the homage of one of the emperors she had made it her business to propitiate. There is something that stirs the imagination in this secret visit of Otho III to the Doge. According to the ingenuous account of John the Deacon, Venetian ambassador at the Emperor’s court, it was merely one of those visits of princely compliment which the age knew so well how to contrive, and loved so well to recount—a visit in disguise for humility or greater freedom, like that of St. Louis to Brother Giles at Perugia, where host and guest embrace in fellowship too deep for words. The Emperor, John the Deacon tells us, was overcome with admiration of Orseolo’s achievements in Dalmatia, and filled with longing to see so great a man, and the chronicler was despatched to Venice to arrange a meeting. The Doge, while acknowledging the compliment of Otho’s message, could not believe in its reality, and consequently kept his own counsel about it—“tacitus sibi in corde servabat.” However, when Otho on his travels had come down to Ravenna for Lent, John the Deacon was again despatched, and this time from Doge to Emperor.

It was ultimately arranged that after the Easter celebration Otho with a handful of followers should repair, under pretext of a “spring-cure,” to the abbey of Santa Maria in the isle of Pomposa at the mouth of the Po. He pretended to be taking up his quarters here for several days, but at nightfall he secretly embarked in a small boat prepared by John the Deacon, and set sail with him and six followers for Venice. All that night and all the following day the little boat battled with the tempest, and the storm was still unabated the next evening, when it put in at the island of San Servolo and found itself harboured at last in the waters of St. Mark. Venice knew nothing of this arrival; her royal guest had taken her unawares, and her waterways had prepared him no welcome. We may picture the anxiety of Orseolo, alone with the secret of his expected guest, on the island of San Servolo. The journey may well have been perilous for so small a boat even within the sheltering wall of the Lido, and we may imagine his relief when it could at last be descried beating towards the island through the tempestuous waters of the lagoon. In impenetrable night, concealed from one another’s eyes by the thick darkness, Emperor and Doge embraced. Otho was invited to rest for an hour or two at the convent of San Zaccaria, but he repaired before dawn to the Ducal Palace and the lodging made ready for him in the eastern tower. There is a fascination in attempting to imagine the two sovereigns moving amid the shadows of Venetian night, in thinking of the Emperor watching from the vantage of his tower for daybreak over the city. There are wonders to be seen from this eastern aspect, but after the discomfort of his voyage to Venice the royal captive may well have felt a longing for a sight of the city from within. It is all rather like a children’s game—Orseolo’s feigned first meeting with an embassy from Otho, his inquiry as to the Emperor’s health and whereabouts, and the public dinner with the ambassadors. Venice is robbed of a pageant, and one most dear to her, the fêting of a royal guest; the guest is deprived of all festivities beyond a christening of the Doge’s daughter; yet the pleasurable excitement of John the chronicler communicates itself and disarms our criticism; and it is not till gifts have been offered and refused—“ne quis cupiditatis et non Sancti Marci tuæque dilectionis causa me hac venisse asserat”—till tears and kisses have been exchanged, and the Emperor, this time preceding his companions by a day, has set sail once more for the island of Pomposa, that we break from the spell of the chronicler and begin to cavil at the strange conditions of the visit.

Modern historians have laid a probing hand on the sentimentality of John the Deacon’s tale; they do not doubt the kisses or the tears, but the unparalleled eccentricity of secrecy seems to demand an urgent motive. Why this strange coyness of the Emperor? Might he not have thought more to honour Venice and her Doge by coming with imperial pomp than by stealing in and out of the triumphant city like a thief in the night? And why did the persons concerned make public boast of the success of their freak immediately after its occurrence? For John tells us that when three days had passed, the people were assembled by the Doge at his palace to hear of his achievement, “and praised no less the faith of the Emperor than the skill of their leader.” The probable solution of the various enigmas rather rudely shatters the romance. Gfrörer lays on Orseolo the responsibility of the incognito, attributing it partly to a memory of the fate that overtook the Candiani’s personal relations with an imperial house, partly to his desire to treat with the Emperor unobserved. He recalls point by point the precautions taken by Orseolo to preclude Otho from contact with other Venetians, and comes to the conclusion that in those private interviews in the tower the “eternal dreamer” was feasted on the milk and honey of promises, food of which no third person could have been allowed to partake. “What lies,” he exclaims, “were invented, what assurances vouchsafed of the most unbounded devotion to imperial projects in general and the longed-for reconstitution of the Roman Empire in particular! Never was prince so shamefully abused as Otho III at Venice.” It is not necessary to abandon our belief in Otho’s personal feelings for the Doge, augmented by Orseolo’s recent campaign, to realise that there must have been another side to the picture. Gulled the royal guest in all probability was, but there is little doubt that he had an axe of his own to be ground on this visit to Venice—that the journey had for its aim something beyond his delectation in a sight of the Doge and his obeisance to the Lion. For the furtherance of his schemes of empire Otho needed a fleet. He had, Gfrörer tells us, “an admiral already in view for it. Nothing was wanted but cables, anchors, equipments; in short there were not even ships, nor the necessary money, and above all, there were no sailors. I believe that Otho III undertook the journey to Venice precisely to procure for himself these necessary trifles. Who knows how many times already he had urged the Doge to hasten his sending of the long-promised fleet; but in place of ships nothing had yet come but letters or embassies carrying specious excuses.” If the historian’s motivisation is accurate, Otho must have found, like so many after him, Venice more capable of exercising persuasion than of submitting to it. For our uses, however, the original or the revised versions of the tale serve the same purpose. As an act of spontaneous homage or an act of practical policy, the visit of Otho, full as it is of speculative possibilities, was an imperial tribute to the position Orseolo had given to Venice, an imperial recognition of her progress towards supremacy in the Adriatic.

Orseolo’s achievement and the rite which symbolised it were confirmed two centuries later when, in the spring and summer of 1177, Venice was the meeting place of Pope Alexander III and the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Tradition has woven a curious romance round the fact of the Pope’s sojourn in Venice before the coming of the Emperor. By a manipulation of various episodes, he is brought as a fugitive to creep among the tortuous by-ways of the city, sleeping on the bare ground, and going forward as chance might direct till he is received as a chaplain—or, to enhance the thrill of agony, as a scullion—in the convent of Santa Maria della Carità, and after some months have elapsed is brought to the notice of the Doge, when a transformation scene of the Cinderella type is effected. It is inevitable that melodramatic touches should have been added to so important an episode, and the accounts of the manner of Alexander’s arrival and his bearing in Venice are many and varied. None the less, it is clear that splendour and not secrecy, ceremony not intimacy, are the general colouring of the event. Frederick had shown himself disposed to make peace and to accept the mediation of Venice, and in the early days of the Pope’s visit the Venetians had acted as counsellors, pending the agreement as to a meeting place. Significant terms are used by the chroniclers to account for the ultimate choice, and the note which they strike is repeated again and again in the chorus of praise that throughout the centuries was to wait upon Venice. “Pope and Emperor sent forth their mandates to divers parts of the world, that Archbishops, Bishops, Abbots, Ecclesiastics and secular Princes should repair to Venice; for Venice is safe for all, fertile and abounding in supplies, and the people quiet and peace-loving.” Secure among the lagoons, Venice is aloof from the disturbances of the mainland cities, and though her inhabitants are proved warriors they are peaceable citizens. Many of the glories of Gentile Bellini’s Procession of the Cross would be present in the procession in which the Doge and the magnates of Venice formally conducted Alexander III to the city—patriarch, bishops, clergy, and finally the Pope himself, all in their festival robes. Ecclesiastical and secular princes of Germany, France, England, Spain, Hungary and the whole of Italy were crowding to Venice. The occasion gave scope for her fascinations, and they were exerted. No opportunity for display was neglected; ceremony was heaped upon ceremony.

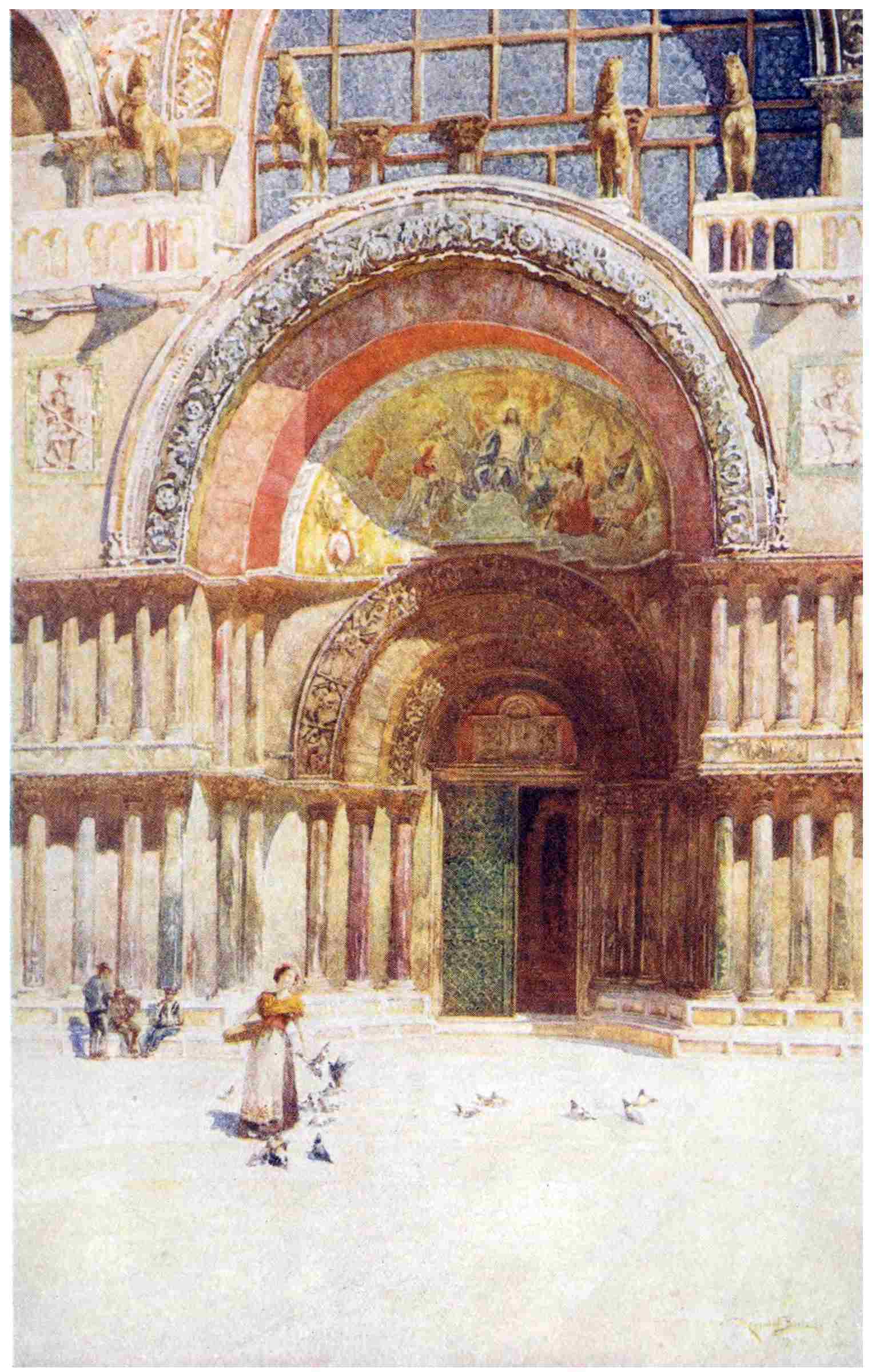

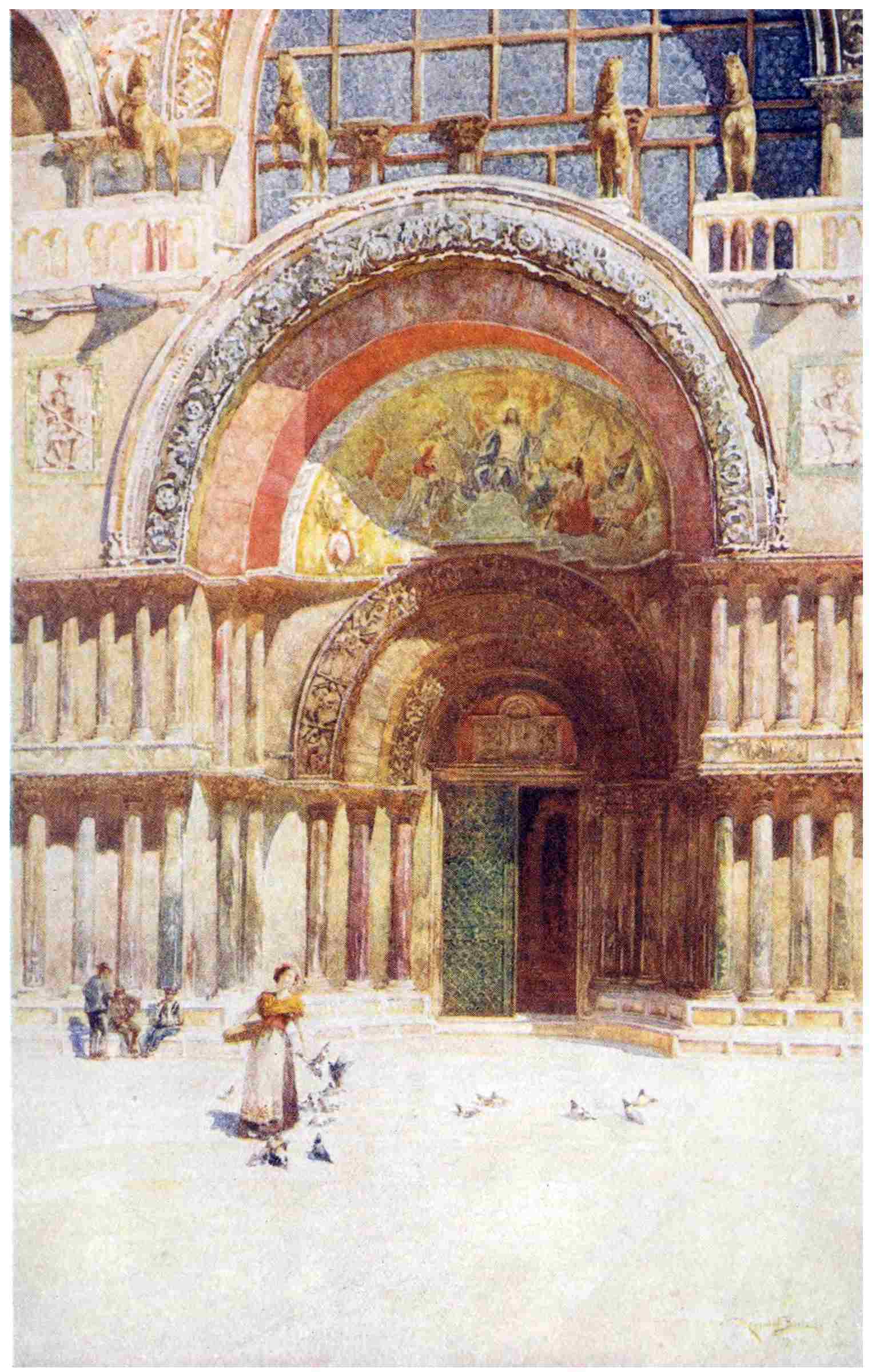

For over a fortnight Venice was the centre of correspondence daily renewed between Emperor and Pope, of embassies hastening to and fro, of endless postponements and uncertainties. The Pope retires for a few days to Ferrara; then he is back again to be received as before. But Venice, the indomitable, is secure of her will, and preparations for the coming of the Emperor are growing apace. In July the Doge’s son is despatched to meet the royal guest at Ravenna and conduct him to Venice by way of Chioggia. No tempests disturbed his arrival. He was conducted in triumph up the lagoon by the galleys of “honest men” and Cardinals who had gone forth to Chioggia to meet him. Slowly the islands of the Lido would unfold themselves to his eyes, Pellestrina in shining curves, Malamocco with its long reaches of bare shore and reeds. The group clustered round Venice itself—San Servolo, La Grazia, San Lazzaro, Poveglia—would be green and smiling then, living islands, not desolated as now for the most part by magazine or asylum. San Nicolo del Lido welcomed the guest, and he was borne thence on the ducal boat to the city and landed at the Riva. Through the acclamations of an “unheard-of multitude” his way was made to San Marco, where the Pope in all his robes, amid a throng of gorgeous ecclesiastics and laymen, was waiting on the threshold. As he passed out of the brilliant and garish day into the solemn mosaiced glory of San Marco and moved to the high altar between Pope and Doge singing a Te Deum, “while all gave thanks to God, rejoicing and exulting and weeping,” even an emperor and a Barbarossa may well have surrendered his pride. Even we, spectators removed by time, find ourselves exalted on the tide of colour and of sound, and crying to the Venetians, with the strangers who thronged in their streets, “Blessed are ye, that so great a peace has been able to be established in the midst of you! This shall be a memorial to your name for ever.” Peace was secured and Venice had accomplished her task. She had devoted the subtleties of her statecraft to its performance, but perhaps the splendour of this hour in San Marco was her crowning achievement. She asked the recognition of a Pope, and she brought the temporal sovereign to his side in a church which is one of the wonders of Christendom. She polished and gilded every detail of her worldly magnificence, and poured it as an oblation at the altar. Her reinforcements to the cause of Alexander III were drawn from far back in the ages, from the inspiration of the men who had fashioned her temple; and may there not be some deeper signification than merely that of Frederick’s stubbornness in the “Not to thee, but to St. Peter,” traditionally attributed to him as he prostrated himself at his enemy’s feet?

THE DOORWAY OF SAN MARCO.

To Venice there remained, beside the praise of all Christendom, many tangible tokens of the events of the summer. Emperor and Pope vied with each other in evincing their gratitude. Alexander formally sanctioned and confirmed the title of Venice as sovereign and queen of the Adriatic, and bestowed on the Doge a consecrated ring for use at the Nuptials. And henceforth the ceremony at San Nicolo del Lido, the place of arrival and departure for the high seas and for Dalmatia and the East, was increased in magnificence. No trace now remains of the church where the rites were performed; but the grassy squares of San Nicolo and the wooded slopes of its canal, looking on one side to the city, on the other to the sea, are beautiful still. The ocean calls to the lagoon, and the calm waters of the lagoon sway themselves in answer; while, outside the Lido, line beyond line of snowy-crested waves, ever advancing, bear in to Venice, Bride of the Adriatic, the will of the high sea.